Golden Age

![]()

This article is about the mythological term. For other meanings, see Golden Age (disambiguation).

Golden Age (Ancient Greek χρύσεον γένος chrýseon génos 'golden generation', Latin aurea aetas or aurea saecula) is a term from ancient mythology. It refers to what is regarded as the ideal peaceful primitive phase of humanity before the emergence of civilization. In a figurative sense, the term Golden Age is used for a period of prosperity. It often refers to an epoch of the highest development of a culture or a period of splendour of a certain form of cultural creation. In addition or alternatively, it can also refer to a period of economic prosperity or political supremacy.

According to the Greek myth - later adopted by the Romans - social conditions in the Golden Age were ideal and people were excellently embedded in their natural environment. Wars, crime and vice were unknown, the modest needs of life were met by nature. However, in the course of the following ages, named after metals of descending quality, increasing moral decay occurred, greed for power and possessions arose and intensified, and living conditions deteriorated drastically. In the present, the lifetime of the myth teller, this development reached an all-time low. Some Roman authors, however, proclaimed the dawn of a new era of peace and harmony as a renewal of the Golden Age.

Ideas that were different in some respects but comparable in important aspects were also widespread in the Near and Middle East in antiquity. From the various versions that have been handed down, the basic features of a primordial myth of Asian origin can be reconstructed. This formed the starting point for various traditions that had a lasting effect on cultural history from Europe to India. There are parallels to the biblical narrative of the Garden of Eden and the expulsion from Paradise (Fall of Man), but there is no discernible basis for a common tradition.

In modern times, numerous writers and poets turned to this theme. Following the ancient models, they often idealized the Golden Age and longed for its return. For some authors, a new motif was added to the traditional characteristics of the mythical primeval age: the ideal of erotic impartiality and permissiveness. Critics, however, judged the idealized simple life in harmony with nature as hostile to progress and culture.

The Golden Age . Painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder, c. 1530, Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Critical, alternative and differentiated positions

A distinction is made between "ascendant" (ascending) and "descendant" (descending) models of cultural history, depending on whether they interpret and evaluate the course of history as progress or as decay. The ancient age myth is a prime example of the descending type. It represents a view and evaluation of cultural history that is one of the most widespread ideas of mankind. With it competed ascendant counter-concepts as well as models combining elements of both views.

Progress idea

The myth of the initial Golden Age paints a picture of an ideal and normative past, from which the subsequent period gradually departed through decadence. The counterposition was the ancient idea of progress. It assumed an animal-like primitive state of mankind; the hardship caused by this forced the formation of communities and the development of technical skills, thus ushering in a beneficial civilizational ascent. Humans invented arts and techniques, or, according to another view, were taught about them by the divine. Such views of man as a deficient being who, through his ability to learn, escaped a primitive state and ascended to civilization were held by Xenophanes, Anaxagoras, and Epicurus, among others.

Differentiated positions

Sometimes the descriptions of philosophers and poets combine individual elements of the ascendant and descendant views. Some authors offer a differentiated account, bringing into focus the ambivalence of both the primordial state of nature and civilization and its consequences.

The poet Lucretius offers a detailed and differentiated theory of the origin of culture. He emphasizes the misery of prehistoric man, who was at the mercy of wild animals and a lack of food, and who lacked medical care. On the other hand, he also takes up elements of the critique of civilization in the world-age myth. In line with mythical lore, he acknowledges the fact that there was no seafaring in prehistoric times as a merit.

In his Georgica, Virgil presents his view of cultural history. In doing so, while he highlights the merits of the mythical primitive age in the usual way, he does not interpret the later development as a mere calamitous decline. Rather, he finds meaning in Jupiter's termination of the Age of Effortlessness. Jupiter had wanted to lead mankind to the achievements of culture, since the excess of inactivity existing under Saturn displeased him. In order to stimulate human ingenuity, the god put an end to the paradisiacal existence and worsened the natural conditions. He created challenges by introducing predatory and poisonous animals and generally made human living conditions dangerous and arduous, so that hardship would make people inventive.

Ovid, who in places echoes Lucretius, does not take a position hostile to civilization, despite his glorification of the mythical Golden Age, but expresses himself differently on different occasions. In a number of places he expresses his positive view of the progress of civilization. In this connection he pays special tribute to erotic love, in addition to agriculture, as a cultivating factor and impulse of development in the cultural history of mankind. He emphatically affirms the refinement of manners. He rejects Virgil's idealization of the rural life of early Rome, and considers the peasant way of life primitive. His criticism of the present refers only to individual aspects such as the pursuit of luxury, the greed for power, and military violence. He appreciates the moral merits of the distant past and the material achievements and refined culture of the present, the latter aspects being of greater importance to him as a whole.

Seneca appreciates "the age called the golden age". According to his conviction, at that time there was a basic correspondence between external nature and man. Nature provided man with what met his true needs. This state of affairs changed only when greed and the unnatural desire for superfluous things arose, and the lust for pleasure provided the incentive for inventions. Despite his critique of civilization, however, Seneca does not condemn all technical inventions. He grants justification to simple technical innovations that did not lead to luxury. Moreover, he notes that philosophy, and with it a pursuit of virtue, could only emerge after the end of the Golden Age. In Seneca's tragedy Medea, the mythical Argonauts' voyage is the expression of human striving for mastery of the sea through seafaring, the introduction of which marks the end of the primeval unison of man and the natural order.

Mockery and condemnation of the idealized primal state

In ancient Greece, there was no shortage of mockers who took aim at the paradisiacal life in the Golden Age "under Kronos" in comedy. In the process, the land of plenty motif took on a life of its own. No longer frugality but natural abundance and the resulting luxury and laziness were now associated with the mythical primeval times.

From an opposite perspective, the Roman poet Juvenal mocked the idealization of the mythical past "under King Saturn" in his sixth satire. According to his ironic description, personified chastity dwelled on earth at that time, but the Silver Age already produced the first adulterers. In the Golden Age a cold cave provided a common close, gloomy dwelling for men and their cattle. Husband and wife dwelt in the mountain forest, sleeping on a bed covered with leaves, stalks, and skins. The wife giving breast to her large children presented a more repulsive sight than her husband belching after the acorn meal. There was no need to fear a thief, for he could have captured only cabbage and fruit.

In his epic De raptu Proserpinae ("On the Rape of Proserpinae"), the late antique poet Claudian has Jupiter, the father of the gods, convene an assembly of gods. In a speech to the assembled gods, Jupiter sharply criticizes the government of his overthrown father Saturn. Here Claudian echoes Virgil's thought of a lack of challenge in the Golden Age. According to Jupiter's account, unproductive idleness prevailed among men at that time. As a result of idleness, a decay occurred which Jupiter equates with the slackening of strength in old age. The uninspiring life of idleness caused mankind to grow weary; it was, as it were, lulled to sleep and stupefied. As Saturn's successor, Jupiter put an end to abundance and luxury. He saw to it that grain no longer grew in uncultivated fields, but that men had to lead a life of care and toil. It was not out of envy and ill-will that Jupiter acted thus; that would be unworthy of a god; gods never inflict harm. Rather, he saw that the sluggish, listless people needed a sting that would snatch them from lethargy and force them into activity. By imposing privations on them, he forced them to train their mental faculties and discover the hidden laws of nature. Thus Jupiter set in motion the progress of culture. By putting these remarks into Jupiter's mouth, Claudian reverses the values of conventional myth. He turns the criticism of decadence that used to be levelled at the post-Saturnian ages against the land of milk and honey of Saturn's golden age. It is not the last but the first age that is old-agey with him.

Bust of Seneca in the Berlin Collection of Classical Antiquities

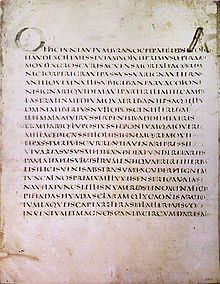

The End of the Golden Age and the Beginnings of Cultural History (Virgil, Georgica 1,121-140 in Codex Vergilius Augusteus)

The comparative study of myths

The oriental origin of the ancient myth

In historical research, until the second half of the 19th century, the view that Hesiod's theory of the ages reflected real facts of prehistory in Greece prevailed. Proponents of this view were Friedrich von Schlegel, Karl Friedrich Hermann and Johann Wilhelm Klingender. The correct counter-opinion, according to which it is a myth without a historical core, was held by Ludwig Preller; at that time it was still a minority position.

In the 20th century, new points of view came to the fore when comparative mythology and religious studies began to take up the subject and uncovered the oriental origins of the saga. Axel Olrik and Richard Reitzenstein played a pioneering role in this. In more recent research, it has become generally accepted that the concept of the metal myth is of oriental origin. However, the question of the extent to which Hesiod's account is a new creation in its own right and the extent to which it depends on older mythical material, in particular the Near Eastern tradition, is controversial. One of Hesiod's own achievements seems to be the linking of the oriental metal myth with the ideas of the time of Kronos that already existed in Greece.

Middle Eastern metal myths

The Near Eastern traditions, like the Greek ones, follow the scheme of epochs according to metals of descending quality. However, they do not deal with a completely fictitious, legendary past, but with known historical conditions of the time since the 6th century BC.

In the biblical book of Daniel, a (divinely inspired) dream is described in which a statue made of various metals appears. The rank of the metals decreases from top to bottom: The head is gold, the chest and arms are silver, etc. The metals symbolize four successive world empires, the first and most important of which, the golden one, is the New Babylonian Empire of King Nebuchadnezzar II.

In the first book of the Persian prophecy Bahman Yašt (6th century AD, but the material comes from much older tradition) a variant from Zoroastrianism is reproduced: Zarathustra sees in a dream a tree with four branches of different metals, representing future great epochs of history, beginning with the golden one, the early days of the Achaemenid Empire. In the golden age, the true religion prevails, and continues to dominate in the two following eras. It is not until the fourth and final age (Iron) that the collapse of morality occurs, with consequences similar to those in the Greek myth. A more recent version of Persian prophecy has come down to us in the second book of Bahman Yašt. It offers a more detailed account and expands the number of epochs named after metals to seven.

Far Eastern Models

In India, a cyclical world-age model has been the only authoritative basis of historical and cultural philosophy for thousands of years. This basic concept has shaped the conception of history in the Vedic religion and Hinduism as well as in Buddhism and Jainism. Through Buddhism, variants of the age model have spread to China and other Far Eastern countries.

According to the Indian world age doctrine, the world is subject to an eternal cosmic cycle in which four ages (yugas) take turns. They are not associated with metals, but with the colors that the god Vishnu assumes in each of the yugas (white, red, yellow and black). The first Yuga is the Krita Yuga ("Perfect Age," also called the Satya Yuga), to which the white color belongs. In the epic Mahabharata the characteristics of this ideal epoch are given. They are similar to those of the ancient European myth: people need not toil, for their desires are effortlessly fulfilled; want, disease, decay, misery, discord, envy, hatred, and treachery are unknown; trade is not carried on; labor is unnecessary. In the succeeding ages there is a progressive decline in the faculties and decay of religion and virtues. The last of these, the black Kali Yuga, forms, as in ancient mythology, the sharpest contrast to the perfect beginning: hatred and criminal violence prevail.

Norse mythology

In Norse mythology, too, the term "golden age" occurs in the creation story. However, it is only attested in the Gylfaginning, which forms the first part of the Snorra-Edda ("Prose-Edda") and was written in Old Icelandic in the first half of the 13th century. In the 14th chapter, the gods are depicted as good craftsmen. They are said to have worked various materials, besides ore, stone, and wood, especially gold, so that they had all their household utensils and furnishings of gold, and this epoch is called the gold age, until it was spoiled by the arrival of certain women from Jötunheim. The gold age is called gullaldr. The use of aldr instead of-as might be expected from a term of Old Norse origin-ǫld suggests that the term gullaldr comes not from a folk tale but from a scholarly tradition. Very likely it is based on Ovid's aetas aurea. Thus the Norse Golden Age term is not of independent origin, but taken from an ancient Roman version of the Golden Age myth. In terms of content, however, there is no correspondence between the Gylfaginning narrative and the Near Eastern and ancient versions of the metal myth.

Intercultural comparison and reconstruction of the primeval myth

Both in Europe and in the Near and Far East, it is a mythical interpretation of history that assumes several successive world ages (or in the Near East: world empires or historical epochs). The ages are characterized by their respective human genera, which differ in terms of their cultural and civilizational levels. The first and best is the Golden Age or Age of the Golden Race, to which in India corresponds the Krita Yuga. This is followed by the Silver Age or Age, etc. Even the second age brings deterioration, which continues later. The conclusion is the Iron Age, which is still continuing, by far the worst of all, with which the lowest possible state of cultural decay is reached. It is therefore the opposite of the idea of progress. The doctrine of the ages is the mythical expression of a culturally pessimistic philosophy of history, which conceives of historical development primarily as a process of natural decay of culture or civilization.

The Indian doctrine of the ages does not appear in the Vedas. Like the Iranian and Jewish versions, it shows similarities with Babylonian cosmography, which points to Babylonian origin. Hesiod's metal scheme, which came to Greece from Asia through Phoenician mediation (the extent and details of Asian influence on Hesiod are disputed), is also Babylonian in origin. Thus an extraordinarily broad Eurasian context of tradition emerges: One can infer a Babylonian primordial myth involving four descending and cyclical successive world ages symbolized by four metals. In each age one of four planetary gods rules. After the end of the world at the end of the fourth, worst age (to which the present of the myth-teller belongs), there is an abrupt return to a new Golden or Perfect Age, with which the cycle is continued. The four colours, which in the Indian tradition stand for the four ages, have there taken over the role of the metals.

Hesiod's version shows some modifications compared to the original myth. In particular, the scheme of the original four metal ages is extended by a fifth age, the epoch of the Heroes, which comes next to last in the chronological order. The Heroes Age forms a foreign body in the scheme, as it is the only one not to bear a metal name, and brings some improvement over the previous age. The destruction and re-creation of mankind at the change of epoch is also an innovation in the variant handed down by Hesiod.

Jean-Pierre Vernant has put forward a structuralist interpretation that has provoked a lively debate, especially in France. According to his hypothesis, the different genders (human species) of the chronologically successive mythical ages reflect a social stratification of society. According to this, Hesiod's golden and silver genders correspond to the rulers (the golden to the good rulers, the silver to the bad), the third and fourth genders are to be interpreted as the warrior class, and the fifth (iron) gender represents the producers of goods. This hypothesis is controversial.

Search within the encyclopedia