Giraffidae

The Giraffidae are a family of even-toed ungulates that includes two genera, the giraffe and the okapi. They are close relatives of the deer and horn bearers. In external appearance, the two representatives differ quite clearly, common unifying features are found in addition to a specially pronounced canine tooth, among other things, in the formation of horn cones as forehead weapons. The family was introduced in 1821 by John Edward Gray, but originally contained only the giraffes. It was not until 1901 with the discovery of the okapi that another representative was added. According to genetic studies, the giraffes today consist of three or four species in up to ten independent populations, while the okapi is represented by only one species.

The animals are endemic to Africa. While the okapi inhabits the tropical rainforests in the central part of the continent, the giraffes are found in the open savannah landscapes of the western, eastern and southern parts. Consequently, the two genera occupy different biotopes, and their respective social structures are adapted to them. The okapi is a predominantly solitary animal, the giraffes live in loose, little structured herd associations. Their diet is based primarily on soft plant foods, with giraffes strongly associated with acacias. Giraffes are one of the few cloven-hoofed animals with a gestation period of over a year, usually giving birth to a single young.

Fossil giraffes have been known since at least the Lower Miocene. The family is very diverse from a phylogenetic point of view, a larger part of its evolution took place outside Africa in southern Europe and from western to eastern Asia. The earliest forms possessed a more deer-like shape. From them arose various lines of development. Some of them have a lengthening of the neck, which is probably a direct predecessor of today's giraffes. In addition, the giraffes also include extinct groups with voluminous bodies and short necks, the most important of which are the Sivatheriinae.

Features

Habitus

The giraffe-like represent large representatives of the even-toed ungulates and include the tallest land-dwelling mammals. The smaller okapi (okapia) has a head-torso length of 200 to 210 cm plus a tail 30 to 42 cm long. Height to the crown is about 180 cm, and body weight is 270 kg, with females being significantly heavier than males. In the much larger giraffes (Giraffa), the head-torso length can be 350 to 450 cm and the tail 60 to 110 cm long. The animals are 450 to 600 cm tall to the crown and measure about 310 cm to the shoulder. The weight varies from 450 to 1930 kg, here bulls are markedly larger than cows. The two genera of the giraffe-like show a somewhat different physique, common to them are extensions in the neck and leg area, which are less pronounced in the okapi than in the giraffe. While the giraffes have an unmistakable appearance due to their extremely long neck and legs, the okapi looks more like a large antelope. The enormous lengthening of the giraffe's neck does not begin until after birth, and is accompanied by the elongation of the seven cervical vertebrae, including the last, so that the junction of the cervical and thoracic spine is set further back than is usual in other ungulates. In normal running, giraffes tend to hold their neck and head upright, only when running fast and climbing mountainsides are both stretched forward. In contrast, the okapi has a more typical ungulate-like head posture. Common to both species are horn-like bone cones covered with skin and fur, which rise above the skull. In the okapi, one pair of these horns is developed, usually occurring only in bulls, and their tips are sometimes free of skin. In giraffes, both sexes bear a paired horn on the head, and rarely a posterior pair of horns is still present on the nape of the neck. However, males often have another, usually smaller horn that grows centrally between the eyes and is considered a secondary sexual characteristic, but can sometimes occur in cows. The long dark-coloured tongue, which is very mobile and capable of grasping, also appears conspicuous. The coat is short haired with average hair lengths of 9.5 mm. Characteristic coat markings appear, which in giraffes consist of a dark spotted or mosaic pattern against a light background. The generally darker, brown-colored okapi shows light horizontal stripes on the legs. In both cases, the coat pattern may be associated with a defensive function. In overall external appearance, the okapi proves to be a typical forest dweller, while the giraffes represent open land forms.

Horns

A special characteristic of the giraffe-like are horn-like outgrowths on the head. In giraffes, the pair of horns is located on the suture between the frontal and parietal bones, the frontal single horn on the frontal and nasal bones. In the okapis, on the other hand, the pair of horns sits on the frontal bone. Compared to similar formations in other forehead weapon bearers, the horns are not particularly large, however; in giraffes they reach a length of up to 19 cm with a circumference of 22 cm, and in the okapi they are still 15 cm long. They have a roughly conical shape with a rounded tip and sit on a horn base that connects the structure to the skull. The horn bases are homologous to corresponding formations in hornbearers (Bovidae) or forkhorn bearers (Antilocapridae). They contain air-filled bone chambers, some of which extend into the horns. The horns themselves have a firm, almost ivory-like structure inside. In contrast to the horns of the horn-bearers, those of the giraffes do not have a keratin coating, but like the horns of the giraffes, they are permanent formations that, unlike the antlers of the deer (Cervidae), are not shed annually. Also different from other horned cloven-hoofed animals, the horns develop in the embryonic stage. Initially they are not yet connected to the skull and consist of spherical cartilaginous tissue embedded in the skin. Only in the course of individual development does the horn ossify from the tip and expand further until it fuses with the skull at about four (males) to seven (females) years of age, although this occurs later in the anterior horn than in the pair of horns. After the horns have fused with the base of the horn, there is only a slight growth in length due to bone rearrangement (secondary bone growth). This rearranged bone substance, which gives the horn a further growth of a maximum of two 2 cm, covers the original horn structure and also buries the blood vessels within the horn. In principle, the pair of horns and the middle horn of giraffes have a similar structure, but the latter is partly not so distinct. The pair of horns is partly called Vellericorni (from Latin vellus for "wool" and cornu for "horn") to separate it from similar formations in other forehead weapon bearers, for the middle horn as a singular formation within the forehead weapon bearers the technical name Giraffacornu (as much as "giraffe horn") has been proposed, which, however, is not generally accepted.

Skull and dentition characteristics

The skull is remarkably large compared to other ungulates and can grow up to 73 cm long in giraffes. However, the sexual dimorphism is strongly pronounced, so that the skull of male animals can weigh up to 12 kg, in females the value is only one third. The skull of the okapi is about 46 to 52 cm long. Distinctive are the extensive air-filled chambers in the top of the skull, which occur mainly in the eye region of the frontal bone and adjacent also in the nasal bone and the parietal bone. The chambers increase the volume of the skull without significantly increasing its weight at the same time. The lower jaw is elongated. The dentition is composed of 32 teeth and has the following dental formula:

Skeletal features

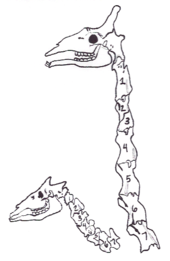

One of the most striking features of the giraffe-like is the long neck of the giraffe, whose bony substructure reaches about half the length of the entire spine. Typically, the cervical spine in mammals consists of seven vertebrae, but what is striking in giraffes is the homogeneous structure of the individual cervical vertebrae compared to the more variable one in the okapi. The individual vertebrae are strongly elongated in giraffes, they have lengths of 17 to 35 cm, with the maximum being reached in the middle of the neck (in the okapi the cervical vertebrae are between 9 and 13 cm long in comparison). Additionally, in giraffes the first thoracic vertebra is strikingly elongated and has only a short spinous process, making it more similar to the cervical vertebrae. However, it has the first rib attachment typical of mammals. The actual transition from the cervical to the thoracic spine is therefore shifted to the second thoracic vertebra. Therefore, it is sometimes argued that the neck of giraffes functionally consists of eight vertebrae. The feature is characteristic of giraffes and does not occur in the okapi or some other extinct representatives of the giraffe-like species such as Sivatherium. Possibly this serves the higher mobility of the neck of the giraffes. Tribal history shows that the extension of the cervical spine began very early. The first forms with an elongated neck are already known from the Middle Miocene, about 14 million years ago, with Giraffokeryx. Intermediate forms to today's giraffe appear in the Upper Miocene with Samotherium and Bohlinia, the former already had cervical vertebrae lengths of 16 to 23 cm. The elongation of the individual cervical vertebrae did not occur evenly and took place first in the anterior part of the vertebra, only later the posterior part elongated as well and finally led to the vertebral structure of giraffes known today. On the other hand, there were also some fossil representatives in which the vertebrae shortened in the course of development, for example in the giant Sivatheriinae. The lengthening of the neck in giraffes was accompanied by a reduction in the size of the horns and the corresponding neck muscles for carrying such frontal weapons.

As in all cloven-hoofed animals, the central axis of the hand and foot runs through the rays III and IV. In the area of the metapodials, the two rays are fused together in the giraffes and form the cannon bone. This is extremely long as well as slender, it can reach up to 75 cm length with the giraffes, with the Okapi up to 33 cm. The laterally attached rays are strongly degenerated and functionless, whereby the inner (ray II) occurs more frequently than the outer (ray V). In contrast to the hornbearers and the deer, the following phalanges (finger- and toe-limbs) have completely developed back.

Comparison of the cervical spine of okapi (left) and giraffes (right)

Skeleton of a giraffe

Skull of a giraffe

Molar teeth of Palaeotragus with the typical selenodont occlusal pattern

Horns of a giraffe

.jpg)

Southern giraffe (Giraffa giraffa)

Distribution

The giraffe-like are now restricted to Africa, but occurred over wide areas of Eurasia in the geological past. Currently, they inhabit the areas south of the Sahara. The giraffes have a rather patchy distribution across western, eastern and southern Africa. They occur in a variety of different open landscapes, ranging from scrub savannahs to woodland savannahs. Their association with acacia shrubs or deciduous vegetation is particularly characteristic. Their relative water independence also enables them to survive in very arid landscapes. In contrast, the okapi is restricted to the tropical rainforests and open forest-savanna mosaic landscapes of the Congo Basin in central Africa. However, they do not appear in gallery forests or very swampy regions.

Search within the encyclopedia