Genghis Khan

![]()

This article is about the Mongolian leader. For the film of the same name, see Genghis Khan (film). For the musical group, see Genghis Khan.

![]()

This article or subsequent section is not sufficiently supported by evidence (e.g., anecdotal evidence). Information without sufficient evidence may be removed in the near future. Please help Wikipedia by researching the information and adding good supporting evidence.

Genghis Khan (Mongol Чингис Хаан, Mongol ᠴᠢᠩᠭᠢᠰ ᠬᠠᠭᠠᠨ, originally Temüdschin, Тэмүжин, ᠲᠡᠮᠦᠵᠢᠨ or Temüüdschin, Тэмүүжин, Tatar "the blacksmith"; * probably c. 1155, 1162 or 1167; † probably 18. August 1227) was a khagan of the Mongols and founder of the Mongol Empire. He united the Mongol tribes and conquered much of Central Asia and northern China. His reign as the first Khagan of the Mongols lasted from 1206 to 1227.

He united the Mongol tribes on the territory of today's central and northern Mongolia and led them to victory against several neighboring peoples. After being appointed Khagan of all Mongols, he began conquering more territories; in the east to the Sea of Japan and in the west to the Caspian Sea. To administer this empire, he had his own script developed and enforced written laws that were binding on all. After his death, the empire was divided among his sons and enlarged even further, but fell apart again two generations later.

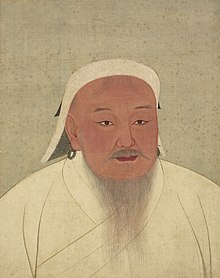

Genghis Khan (14th century portrait)

Life

Situation of the Mongols

The Mongols originally settled in the northeast of present-day Mongolia, between the Onon and Kerulen rivers. They were composed of nomadic pastoral tribes of the steppe and hunters and fishermen of the forest areas and were fragmented into numerous smaller groupings.

The grazing area was (and still is) common property, ownership rights to land were unknown. Nevertheless, due to the unequal distribution of livestock ownership, an early feudal order existed within the individual tribes. Across tribes, leaders for warfare, raiding and hunting were still freely chosen by the tribal princes at a kurultai around 1200, but a military aristocracy emerged in the unification struggles of that time, which gained a great deal of power in the course of the development of Mongol warfare and whose leadership positions eventually became hereditary under Genghis Khan.

Origin and birth

According to Mongolian legend, Genghis Khan's family tree (and that of all Mongols) began with a wolf and a doe that settled near the sacred mountain of Burchan Khaldun on the banks of the Onon River. This mountain lies about 170 km east of today's Ulan Bator and is part of the Chentii Mountains, where the rivers Kerulen and Tuul also rise.

Genghis Khan belonged to the Mongghol tribe, the Borjigin clan (wild duck people) and the Qiyat (Kijat) sub-clan. He was the eldest son of the clan chief Yesügai and his wife Hoe'lun-Ujin (also Üdschin) and also the great-grandson of the legendary Mongol prince Qabul (also known as Kabul Khan), who had temporarily united the Mongol tribes around 1130-1150, and received the name Temüdschin (Tatar.: "the blacksmith", wrongly translated as "the iron one") from his father. According to old Mongolian custom, this name came from a captured enemy.

In the epic The Secret History of the Mongols, commissioned by Genghis Khan's son and successor Ögedei only after his death, it is reported that Temüdschin held a blood clot in his right fist at birth, at that time for the Mongols a prophetic sign of strength and willpower. The birthplace is said to be Burchan Chaldun on the upper reaches of the Onon.

Childhood and youth

At that time, the clans of the steppe were involved in constant fighting among themselves. Temujin's father Yesügai had greatly increased the tribal territory by raiding the Tartars and the Mercites and had accumulated wealth and prosperity. In one of these raids, he even robbed Temujin's mother directly from her Mercite groom's wedding carriage and made her his own wife. In his childhood, Temujin learned early on how to ride a horse, shoot an arrow, and hunt, skills then crucial to survival on the steppes of Central Asia. As was so often the case with nomadic peoples, the law of the strongest applied there as well, taking what he needed without consideration. For this reason, however, every raid and robbery was followed by the threat of revenge on the part of the inferior, as Temüdschin was later to experience for himself.

According to reports, as a young boy he was initially rather timid and shy, but he developed a close bond with his brother-in-law Dschamucha, who was later to become his bitterest enemy out of rivalry.

Temüdschin was nine years old when his father, as was customary at that time among the Mongolian nomads, went with him on a bride search. In the camp of a friendly clan of the Unggirat tribe they discovered a small, pretty girl named Börte. She was the daughter of the tribe's leader, to whom they asked for her hand in marriage. Since the leader agreed, the future bridegroom stayed with his parents-in-law for some time and made friends with his fiancée.

His father rode back alone, accepting the hospitality of Tartars on the way. However, these recognized him as the head of the enemy tribe and poisoned him during the meal. Informed by a messenger of his father's death, Temudshin returned to his tribe. Because of his youth, however, he was not recognized there as his father's successor. The former retainers turned their backs on his family, the whole clan disbanded, and he was left as the eldest son with his mother, his three adolescent brothers, and a younger sister. Without the protection of the tribe, they were gradually robbed of all their possessions, and lived in poverty for the next few years. There were frequent quarrels between him and his brothers, which finally culminated in his murdering his half-brother Bektar. According to another source, he killed his brother in a quarrel over the booty after a raid.

For other Mongol princes, despite his deplorable living conditions and youth, he nevertheless posed a threat simply because of his aristocratic lineage, and the family had to flee time and again. Sometimes Temudshin is said to have sought refuge at the holy mountain of Burchan Khaldun in the times of greatest distress. On one of these escapes he was finally captured by the Taijut, held like a slave, and severely humiliated. Through his adventurous escape from this captivity, he gained great renown among his peers. He also found his fiancée Börte again, whom he eventually married.

unification of the Mongols

Temüdschin knew that one can only survive in the steppe if one has powerful allies. Through skillful diplomacy, he managed to gradually win over his opponents or eliminate them.

In 1190 he thus united the Mongolian clans, which then began under his leadership to subjugate the neighboring steppe peoples. As an incentive for the unconditional obedience of his fighters, he promised them rich booty on the coming war campaigns.

In 1201 he succeeded in defeating his most active rival and former oath-brother, the Gurkhan Jamukha. The latter was able to flee at first, but lost a large part of his following. In the desperate struggle against Temüdschin, he entered into constantly changing alliances with friend and foe. This hopeless interplay finally became too much for his closest confidants, and they handed him over to Temüdschin. He, however, set an example which was characteristic of him. Since he hated nothing so much as disloyalty and treachery, he had the henchmen of Dzhamukha and all their family members killed. To his former blood brother, on the other hand, he again offered his friendship and asked him to return to his side. The latter refused the offer and asked for a death befitting his rank, which was granted. Later, Temudshin defeated Kushluq, who had fought against him with the Kara-Kitai.

In 1202, after a victory over the Merkites in the north, Temudshin felt strong enough to retaliate against the Tartars in the east for the death of his father. In bloody battles he defeated the four tribes of the Tartars, and according to the information in the Secret History of the Mongols he left alive among the vanquished only those who were not taller than the axle height of an ox-cart. In 1203 he defeated the Keraites under Toghril Khan and Nilkha, and in 1204 the Naimans under Tayang Baybugha in the west. Thus the last hurdles on the way to unrestricted power were overcome.

Appointment to Genghis Khan and changes

In 1206, Temudshin convened an imperial day at the source of the Onon, the so-called Kuriltai. There he was appointed "Genghis Khan", the Great Khan of all Mongols, by the shamans and tribal lords present and awarded the title of "impetuous ruler" (oceanic ruler). The emblem of sovereignty awarded to him, the white standard, still stands today in the Mongolian Parliament, together with nine other standards for the core tribes of the empire at that time, as the symbol of the present Mongolian state. The three prongs at the top of the standard represent the moon, the sun and the flame and are supposed to symbolize the strength of the Mongols. The moon symbolizes the past, the sun the present and the flame the future of the Mongol Empire.

By the decision of the Imperial Diet, a new state was created with Genghis Khan as the unrestricted ruler and sole legislator. The government was formed by his mother, brothers and sons. From representatives of other nations he learned how to administer a great empire. To this end, he ordered his son Ögedei to write down the old and newly enacted laws in the form of a basic Mongolian law, the Jassa. This work formulated a unified collection of strict commandments and regulations that were to govern coexistence in the newly founded Mongol Empire. This put an end to the arbitrary rule of the tribal princes and created an essential basis for an orderly state. According to another source, he had the Jassa recorded by his adopted Tatar son Shigiqutuquals, who knew how to write, and also made him his chief judge.

Next, he established universal conscription and appointed thousand-ship leaders from among his previous companions to lead his great army. For these and other appointments, blood relationship or tribal affiliation was no longer decisive, but unconditional obedience to the Khan and special bravery in previous battles. The old tribal nobility was largely disempowered and replaced by reliable people (quiver bearers) from the military. Unreliable tribal groups were disbanded. These measures meant a revolutionary break with the previous social conditions of the steppe. The new order replaced treachery and deceit with discipline and allegiance.

Occasionally Genghis Khan would bring his wife or mother a young boy from each of the subjugated tribes. These children were adopted by them and subsequently grew up as equal family members together with the Khan's biological sons. Thus, a group of young, often talented men always grew up in his yurt.

In addition to the well-organized and strictly disciplined army, the only reliable means of power against the traditional independence of the tribal nobility, the new Great Khan also established his own bodyguard of about 10,000 soldiers. These were composed of the sons or brothers of tribal lords and military leaders, who on the one hand fought for him as warriors, but at the same time represented a pawn as hostages to ensure the unconditional obedience of the steppe nobility.

It was not until around 1220 that enough foreign officials came into Mongol service so that one could also think of a kind of civil administration of the subjugated peoples.

Genghis Khan was illiterate himself, but nevertheless recognized the importance of writing and therefore had his own script developed for the administration of his empire. This is how the Mongolian script, derived from Uyghur, came into being.

Further conquests

Following the unification of the empire, Genghis Khan turned to the conquest of China from 1207. Subsequently, the Mongol army conquered the Xixia Empire of the Tanguts, the Jurchen Empire in present-day north and northeast China, and the rich Muslim kingdoms in present-day Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Iran, Afghanistan, and Turkey; small kingdoms submitted to it as vassals. It is estimated that about 30% of the population perished in the violent incursions of the Mongol army. Genghis Khan made a point of sparing artists, architects, and administrators in the massacres because he needed them to build his own empire. After subduing the Tanguts in 1209, he created a camp south of the Great Wall for further conquests. In 1211, he led his forces of more than 100,000 fighters south and east into territory dominated by the Jin Dynasty, advancing as far as the Shandong Peninsula. In 1215, after a successful siege of Beijing, he took Shandong, and in 1219 Korea also paid tribute to him.

In 1217, the Khan instructed his general J̌ebe Noyan to bring down the Naiman Güčülük. After the defeat of the Naimans by Genghis Khan's forces in 1204, Tayang Baybugha's son Güčülük had fled to the Kara-Kitai Empire and seized power there. Güčülük, who was hated by the people, once again took flight. J̌ebe pursued him to Badakhshan in present-day Afghanistan, where Güčülük met his death in 1218. Kara-Kitai then submitted peacefully and so the last remaining steppe kingdom at Lake Balchash fell.

In the West, a treaty of friendship was concluded with the Islamic Khorezmian Empire in Persia, but the peace lasted only a short time. Soon after, a Mongol caravan was attacked there and the travelers murdered.

Imperial Assembly and the Question of Succession

Genghis Khan then convened another imperial assembly in 1218 to decide on a retaliatory strike against this empire in the west and further laws and directives. At the same time, he also wanted to settle the question of succession during his lifetime. His eldest son was Jötshi († 1227), the second Chagatai († 1242), the third Ögedei († 1241), the fourth Tolui († 1232).

At first, during this clarification, a violent quarrel arose among the sons, and the eldest was violently scolded by all the others. But then, when one of them proposed for conciliation that Ögedei should be chosen as successor, Genghis Khan at once agreed to this, as his middle-born son was considered prudent and generous. So, in this sense, his succession was contracted at this meeting and, moreover, a vendetta against the Khorezmian Empire was also decided.

Genghis Khan's wife Börte Ujin had been abducted by the hostile Merkite tribe before the birth of Genghis Khan, so there was some doubt about Genghis Khan's paternity of his firstborn son. Thus the name of the latter, Jötschi, means the stranger, and from this arose the dispute between the two eldest sons as to which of these was really the first-born.

Retaliation

In 1219/20 the Mongols defeated the forces of the Khorezm Shah in Transoxania. Bukhara and Samarkand were conquered, and Sultan Ala ad-Din Muhammad died in flight at the Caspian Sea. His son Jalal ad-Din was defeated on the Indus River in 1221 and temporarily fled to India.

Foundation of Karakorum

In 1220 Genghis Khan designated the site of the later city of Karakorum (black mountains/black rock/black rubble), at first probably only as a special residence on the banks of the Orkhon for his stay in the Helin area, since similar residences already existed for his stay in other areas of his country.

However, the Orkhon was and is the lifeline of the entire region, and on its banks lay the centers of great past steppe empires even before Genghis Khan. By establishing his residence at this very spot, he consciously placed himself in the tradition of his predecessors. To consolidate his power, Karakorum later became the first capital of the Mongol Empire and was also fortified under his successor. For the Mongols, Karakorum is still the historical centre of their nation state.

Genghis Khan brought foreign craftsmen and artists into the country, especially to the new capital, in order to carry out activities that were previously unfamiliar to the nomads. However, the Mongols did not usually acquire the knowledge of the foreigners, but they let them work for them. Some of the foreign craftsmen and artists came voluntarily, but others were also brought here.

Genghis Khan and his successors showed a second, completely different face in Karakorum besides their war deeds. Through their tolerant attitude towards everything new and unknown, their capital became not only the control centre of the imperial administration and a centre of trade and arts and crafts, but also a melting pot of different religions, cultures and peoples.

Campaigns to Eastern Europe

About the same time (1220) the Mongols attacked the Caucasus and southern Russia, and in 1223 the troops under J̌ebe and Sube'etai advanced as far as the Ukraine. There they defeated the Rus and Kipchaks at the Battle of the Kalka. At this time the Mongols had not come to make conquests and retreated into Mongolia after their victory. It was not until Genghis Khan's successor Ögedei that the Mongols returned to Eastern Europe fifteen years later and, in what became known as Mongol Storm, subdued Rus and advanced as far as Hungary, Poland, and Austria. Sube'etai was also involved in this campaign as commander.

Death and succession

In 1224/25 the Khan returned to Mongolia with the plan of a punitive expedition against the Tanguts. On the way there he died, probably on August 18, 1227. The cause of death is not clear, according to the most widely accepted account he succumbed to internal injuries after a riding accident. According to the Galician Volhynian Chronicle, he was killed by the Tanguts. Folk lore also tells of a Tangut princess who sought to avenge her people and forestall her own rape by emasculating him with a hidden knife. The Italian paleontologist Franceso Galassi assumes that Genghis Khan died of the plague. The high fever and the quick death within a week speak for it. In addition, his army was decimated by the plague.

When Genghis Khan died in 1227, all living creatures in his surroundings, including 2000 people who had attended the funeral, were killed. According to Mongolian tradition, the location of the burial place was kept secret and to this day Genghis Khan's grave has not been found.

His burial place is said to have been levelled by a thousand horsemen with the hoofs of their horses, and they are said to have been executed immediately on their return, so that they could not reveal the exact spot to anyone. It is generally believed that Genghis Khan was buried in the Chentii Aimag somewhere on the southern slope of Burchan Khaldun, as this mountain had played an important part in his life, but there are so many legends surrounding his burial that other burial sites are also possible. One that can be ruled out with certainty is the site of the Genghis Khan Mausoleum near Ordos in Inner Mongolia. This is a memorial with an empty coffin and not a real tomb, i.e. a cenotaph.

When Genghis Khan died, his empire had reached a size of 19 million km² and was thus twice as large as today's China. It now stretched from the China Sea in the east to the Caspian Sea in the west and is still the only nomadic state in the world that lasted for 200 years. But it was only under Genghis Khan's successors that it would reach its final expansion and become the largest world empire in human history to date.

Against all tradition, but true to his principle that competence and aptitude decide, Genghis Khan had appointed the second youngest son Ögedei as his successor during his lifetime at the imperial assembly of 1218. Normally, in the Mongol succession, the youngest son succeeded his father and inherited his possessions - minus the share of the elder sons. True to the agreement, the new Great Khan Ögedei was proclaimed ruler of all Mongols at a convened Imperial Diet in 1229.

In addition, the subjugated peoples and their territories were divided among Chagatai, Ögedei and Tolui, as well as the descendants of the deceased fourth son Jötschi. Each got his own sub-kingdom (khanate). Together, the four families continued to expand the empire until they finally fell out (cf. Genghisid Master List).

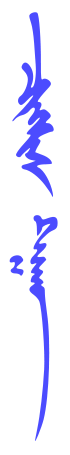

"Genghis Khan" in classical Mongolian.

The Mongol Empire at the Death of Genghis Khan (1227)

The Mongol Empire under Genghis Khan and his successors. Expansion under Genghis Khan and successors oaks 1294: Golden Horde Chagatai Khanate Ilchanat Yuan Dynasty (Great Khanate)

Military Organization

→ Main article: Mongol warfare

The Mongol army was organized according to the decimal system. The troops were arranged in tens, and the men controlled each other. If one warrior fled from the enemy, the other nine had to die as well. By handing over horsehairs, one hair from each horse of each soldier, the army leaders swore unconditional obedience to the khagan. From these bundles of horse hair was born the Black Standard, the new field emblem of the Mongols. This standard is still kept today as an important national symbol in the Ministry of Defense in Ulaanbaatar.

The power of the new army was based on its strict discipline, its agility on the tough and persistent horses, its weapons and its sophisticated battle tactics. Each horseman carried two or three horses and was able to cover great distances in a very short time, thanks to the possibility of exchanging them at all times. On the way they only stopped to eat and sleep. Among other things, the fighters carried dried meat powder (borts) in cow bladders attached to the saddle as provisions. Borts is easily portable and virtually nonperishable, and is boiled in hot water like bagged soup today. With this energy-giving and nutritious food, they could sustain themselves for months.

All Mongols were trained from childhood as horsemen and archers. Hunting was considered to them the school of war. Their main weapon was a special composite bow. They always carried several bows and many arrows with forged iron tips. The composite bows gave the arrows they shot a high penetrating power. By using stirrups, they could also shoot arrows backwards (Parthian maneuver).

A frequently used battle tactic consisted of a short attack followed by a feigned retreat to lure the pursuing enemy into an ambush. At a higher level, an attempt was made to encircle and destroy the enemy army in whole or in part. This approach and the organization required for it probably derived from experience with kettle hunting in the steppe.

Mounted archers of the Mongolsfrom the universal history of Raschid ad-Din

Questions and Answers

Q: Who was Genghis Khan?

A: Genghis Khan was a Mongolian ruler who became one of the world's most powerful military leaders.

Q: What did Genghis Khan do?

A: Genghis Khan joined with the Mongol tribes and started the Mongol Empire. He was a very successful emperor in battles, conquering many other peoples such as the Jin Dynasty. He occupied much of China and some surrounding countries of China.

Q: Who started the largest empire in the world?

A: Genghis Khan's children and his grandchildren started the largest empire in the world.

Q: Who was Kublai Khan?

A: Kublai Khan was the first ever emperor of the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) in China. He was the grandson of Genghis Khan.

Q: What was Genghis Khan's real name and its meaning?

A: Genghis Khan's real name was Temüjin which means iron worker.

Q: Why was Genghis Khan called "Universe ruler"?

A: People referred to Genghis Khan as "Universe ruler" because of his military success.

Q: Where and when did Genghis Khan die?

A: Genghis Khan died in the Liupan Mountains in northwestern China in Aug. 1227. His burial site is unknown.

Search within the encyclopedia