Geneva Conventions

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Geneva Convention.

The Geneva Conventions, also known as the Geneva Conventions, are intergovernmental agreements and an essential component of international humanitarian law. They contain rules for the protection of persons not or no longer participating in hostilities in the event of war or international or non-international armed conflict. The provisions of the four 1949 Conventions concern the wounded and sick of armed forces in the field (Geneva Convention I), the wounded, sick and shipwrecked of armed forces at sea (Geneva Convention II), prisoners of war (Geneva Convention III) and civilians in time of war (Geneva Convention IV).

On 22 August 1864, the first Geneva Convention "Relative to the Relief of Military Persons Wounded in the Field" was adopted by twelve States in the Geneva Town Hall. The second convention from a chronological point of view was the current third Geneva Convention, adopted in 1929. Together with two new conventions, both conventions were revised in 1949. These versions entered into force one year later and represent the currently valid versions. They were supplemented in 1977 by two Additional Protocols, which for the first time integrated rules on the treatment of combatants as well as detailed provisions for internal conflicts into the context of the Geneva Conventions. In 2005, a third Additional Protocol was adopted to introduce an additional sign of protection.

The depositary state of the Geneva Conventions is Switzerland; only states can become contracting parties. At present, 196 countries have acceded to the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and 174 and 168 countries respectively have acceded to the first two Additional Protocols of 1977; 72 countries have ratified the third Additional Protocol of 2005. The only controlling body explicitly named in the Geneva Conventions is the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The Geneva Conventions are unilaterally binding law for the signatory states. The law agreed upon therein is to be applied to everyone.

Signing of the first Geneva Convention in 1864, painting by Charles Édouard Armand-Dumaresq

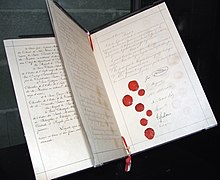

Original document of the first Geneva Convention, 1864

Original document, single pages as PDF, 1864

History

See also: Chronological development of international humanitarian law

Beginning 1864

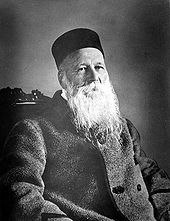

The development of the Geneva Conventions is closely linked to the history of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). The Geneva Conventions, like the ICRC itself, have their origins in the experiences of Henry Dunant, a Geneva businessman, following the Battle of Solferino on 24 June 1859, which he published in a book entitled A Memoir of Solferino in 1862. In addition to describing his experiences, the book contained suggestions for the establishment of voluntary aid societies and for the protection and care of the wounded and sick in war.

The implementation of Dunant's proposals led to the foundation of the International Committee of Relief Societies for the Care of the Wounded in February 1863, which has borne the name International Committee of the Red Cross since 1876. As part of these efforts, the first Geneva Convention was adopted at a diplomatic conference on 22 August 1864.

Twelve European states were involved: Baden, Belgium, Denmark, France, Hesse, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Prussia, Switzerland, Spain and Württemberg. In December of the same year, the Scandinavian countries Norway and Sweden joined. Article 7 of this convention defined a sign to identify the persons and institutions under its protection, which became the eponymous symbol of the newly created movement: the Red Cross on a white background. The Geneva jurist Gustave Moynier, who as president of the Geneva Public Benefit Society had initiated the foundation of the International Committee in 1863, played a major role in the drafting of the Convention.

Why it came to the adoption of the convention in a relatively short time after the publication of the book and to its rapid spread in the following years cannot be fully understood historically. It can be assumed that at that time there was a widespread opinion among politicians and military leaders in many countries that the near future would bring a series of inevitable wars. This position was based on the generally accepted ius ad bellum ("right to wage war") at the time, which regarded war as a legitimate means of resolving interstate conflicts. Behind the acceptance of Dunant's proposals may therefore have been the idea that the inevitable should at least be regulated and "humanized." Second, the very direct and detailed description in Dunant's book may have brought the reality of war home to some leaders in Europe for the first time. Third, in the decades following the founding of the International Committee and the adoption of the Convention, a number of nation-states emerged or consolidated in Europe. The national Red Cross societies that emerged in this context also had an identity-forming effect. They often acquired a broad membership base within a short time and were also generously promoted by most states as a link between the state and the army on the one hand and the population on the other. In a number of states this was also done with a view to a transition from a professional army to general conscription. In order to maintain the population's will to go to war and their support for this step, it was necessary to ensure the impression of the best possible provision for the soldiers.

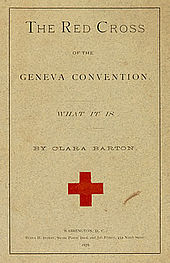

The first signatories did not include the United Kingdom, which had attended the 1864 conference but did not join the convention until 1865, and Russia, which signed the convention in 1867. Surviving is the statement of a British delegate during the conference that he could not sign the convention without a seal. Guillaume-Henri Dufour, General of the Swiss Army, member of the International Committee and Chairman of the Conference, then cut a button from his tunic with his penknife and presented it to the delegate with the words "Here, Your Excellency, you have Her Majesty's coat of arms". Austria, under the impression of the Prussian-Austrian War of 1866, acceded to the Convention on 21 July 1866, and the German Empire, founded in 1871, on 12 June 1906. Important predecessor states, however, had become parties to the Convention before then. Hesse, for example, ratified the Convention on 22 June 1866 after having signed it as early as 1864, and Bavaria acceded on 30 June. In both cases, this occurred as a direct result of the war between Prussia and Austria. Saxony followed on 25 October 1866. The USA, which had also been represented at the conference, had major reservations for a long time, particularly because of the Monroe Doctrine, and did not accede to the Convention until 1882. The work of Clara Barton, the founder of the American Red Cross, had a great influence. In total, 57 states signed the Convention in the course of its history, 36 of them within the first 25 years from 1864 to 1889. Ecuador was the last state to accede to the 1864 Convention on 3 August 1907, just six days before the revised version of 1906 came into force.

Further development until the Second World War

As early as 1868, supplementary articles to the Geneva Convention were proposed for the first time in order to extend its scope to include naval warfare. However, despite being signed by 15 states, this proposal was not ratified by any country and was thus never implemented due to lack of support. Only the USA became a party to the Geneva Convention by acceding to it in 1882. Nevertheless, the parties to the conflict in the Franco-Prussian War (1870 to 1871) and in the Spanish-American War of 1898 agreed to observe the rules formulated in the Additional Articles. Then, at the end of the 19th century, on the initiative of the Swiss Federal Council, the International Committee again drew up a draft to this effect. At the first Hague Peace Conference in 1899, without the direct participation of the ICRC, Hague Convention III was concluded, adopting in 14 articles the rules of naval warfare of the Geneva Convention of 1864. Under the impact of the naval battle at Tsushima on 27 and 28 May 1905, this convention was then revised during the second Hague Peace Conference in 1907. The agreement, known as Hague Convention X, took over almost unchanged the 14 articles of the 1899 version and, in terms of expansion, was essentially based on the revised Geneva Convention of 1906. These two Hague Conventions were thus the cornerstone of the Geneva Convention II of 1949. The most important innovation in the 1906 revision of the Geneva Convention was the explicit mention of voluntary aid societies to assist in the care of the sick and wounded soldiers.

The further historical development of international humanitarian law was primarily shaped by reactions of the community of states and the ICRC to concrete experiences from the wars since the conclusion of the first convention in 1864. This applies, for example, to the agreements adopted after the First World War, including the Geneva Protocol of 1925 in response to the use of poison gas. However, contrary to widespread belief, this agreement is not an additional protocol to the Geneva Convention, but belongs in the context of the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. The League of Nations, which came into being in 1920, was largely responsible for its creation instead of the ICRC; the depositary state of this protocol is France. The most important impact of the First World War on that part of international humanitarian law which is in the Geneva tradition was the Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War in 1929, in response to the massive humanitarian problems in the treatment of prisoners of war during the First World War. This convention marked the first time that the International Committee was explicitly mentioned in international humanitarian law. Article 79 gave the ICRC the possibility of proposing to the parties to the conflict that they set up and organise a central office for the exchange of information on prisoners of war.

Similarly, the first Convention was revised again in that year, although not as extensively as the 1906 version of 1864. One important change, however, was the removal of the so-called all-parties clause (clausula si omnes), which had been newly included in 1906 in the form of Article 24. According to this clause, the Convention was only to apply if all parties to a conflict had signed it. Although the clause would have been relevant, for example, with the entry of Montenegro into the First World War, no country ever invoked it during the period of its validity from 1906 to 1929. Since it did not actually correspond to the humanitarian concern of the Geneva Convention and had also always been rejected by the ICRC, in retrospect it can only be assessed as a wrong decision and was consequently deleted from the Convention during its revision in 1929.

A second significant change was the official recognition of the Red Crescent and the Red Lion with Red Sun as equal signs of protection in Article 19 of the revised version of the first Geneva Convention. The Red Lion, used exclusively by Iran, has not been in use since 1980, but must be respected as a continuing valid sign of protection if used. Moreover, in its declaration of 4 September 1980, Iran reserved the right to reuse the Red Lion in the event of repeated violations of the Geneva Conventions in respect of the other two marks.

As early as the 15th International Red Cross Conference in Tokyo in 1934, a draft convention for the protection of civilians in wartime was adopted for the first time. A decisive role was played by Marguerite Frick-Cramer, who in 1917 became the first woman delegate of the ICRC and a year later was the first woman to be elected a member of its governing body. The positive decision in Tokyo followed resolutions of previous conferences that had called on the ICRC to take appropriate steps in the light of the experience of the First World War. The diplomatic conference of 1929 had also unanimously declared itself in favour of such a convention. A conference planned by the Swiss government for 1940 to adopt the draft did not take place because of the Second World War. Appeals by the ICRC to the parties to the conflict to voluntarily respect the Tokyo draft were unsuccessful.

Geneva Convention of 1949

In 1948, under the impact of the Second World War, the Swiss Federal Council invited 70 governments to a Diplomatic Conference with the aim of adapting the existing body of rules to the experiences of the war. The governments of 59 states accepted the invitation, and twelve other governments and international organizations, including the United Nations, participated as observers. The International Committee of the Red Cross and the League of Red Cross Societies were brought in as experts by decision of the Conference. During the conference, which lasted from April to August 1949, the existing two conventions were revised and the rules of naval warfare, which had previously existed as Hague Convention IV, were incorporated into the Geneva Conventions as a new convention. The Geneva jurist and ICRC member Jean Pictet, who is thus regarded as the intellectual father of the 1949 Conventions, played a major role in drawing up the drafts submitted by the ICRC. The legally fixed mandate of the International Committee was considerably expanded by the four conventions. At the conclusion of the Diplomatic Conference, the conventions were signed by 18 states on 12 August 1949.

The conclusion of Geneva Convention IV "relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War" was the most important extension with regard to the scope of the Geneva Conventions; it is a direct consequence of the experience with the devastating effects of the Second World War on the civilian population and is essentially based on the draft of 1934. One year after the conference, the four currently valid conventions entered into force on 21 October 1950. Austria and Switzerland were among the signatories, as was the USA on 12 August 1949. Switzerland was the first country in the world to ratify the conventions on 31 March 1950, Austria followed on 27 August 1953. By the time the conventions entered into force on 21 October 1950, Monaco on 5 July, Liechtenstein on 21 September and Chile on 12 October followed with further ratifications, and India also acceded to the conventions in the same year on 9 November. The Federal Republic of Germany became a party to the treaties in a single act on 3 September 1954, with no distinction between signature and ratification, followed by the German DemocraticRepublic on 30 August 1956. In the same year, the number of contracting parties reached 50; eight years later, 100 states had already acceded to the 1949 Conventions.

Additional Protocols of 1977

As a result of the wars in the 1960s, such as the Vietnam War, the Biafra conflict in Nigeria, the wars between the Arab states and Israel, and the wars of independence in Africa, the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution 2444 (XXIII) "Respect for Human Rights in Armed Conflicts" on 19 December 1968. This resolution reaffirmed the general validity of three fundamental principles of international humanitarian law: (1) the existence of limitations on the choice of means of warfare; (2) the prohibition of attacks against civilians; (3) the obligation to distinguish between combatants and civilians and to spare civilians as much as possible. In addition, this resolution called upon the UN Secretary-General, in cooperation with the ICRC, to examine the extent to which the applicability of existing IHL regimes could be improved and the areas in which there was a need to expand IHL through new agreements. This was the impetus for the Diplomatic Conference of 1974 to 1977.

At the end of this conference, two additional protocols were adopted, which entered into force in December 1978 and brought substantial additions in several areas. On the one hand, both protocols integrated into the legal framework of the Geneva Conventions rules on permissible means and methods of warfare and thus, above all, on the treatment of persons involved in hostilities. This was an important step towards the unification of international humanitarian law. The rules of Additional Protocol I also clarified, above all, a number of provisions of the four 1949 Conventions whose applicability had proved inadequate. Paragraph 2 of Article 1 of the Protocol further adopted from the Hague Land Warfare Regulations the so-called Martens Clause, which provides the three principles of custom, humanity and conscience as standards of action for situations not expressly governed by written international law. Additional Protocol II was a response to the increase in the number and severity of non-international armed conflicts in the post-World War II period, particularly in the context of the liberation and independence movements in Africa between 1950 and 1960. It realized one of the ICRC's longest-standing objectives. Thus, in contrast to Additional Protocol I, Additional Protocol II is not so much an addition to and clarification of existing rules as an extension of international humanitarian law to an entirely new area of application. In this sense, it can be regarded more as a separate and additional convention and less as an additional protocol. Austria and Switzerland signed the Protocols on 12 December 1977, and Ghana was the first country in the world to ratify on 28 February and Libya on 7 June 1978, followed by El Salvador on 23 September before the entry into force on 7 December of the same year. Switzerland ratified on 17 February 1982, followed by Austria on 13 August 1982. Germany signed the Protocols on 23 December 1977, but did not ratify them until some 13 years later on 14 February 1991. In 1982, 150 states were parties to the 1949 Geneva Conventions. Additional Protocols I and II recorded 50 parties in 1985 and 1986 respectively, and the figure of 100 was reached just six years later.

Developments and problems after 1990

The renewed rise of independence movements after the end of the Cold War and the rise of international terrorism, both of which were accompanied by a significant increase in the number of non-international conflicts involving non-state parties to the conflict, presented the ICRC with massive challenges. Inadequacies in the applicability and enforceability of the two 1977 Additional Protocols in particular, as well as a lack of respect for the Geneva Conventions and their safeguards among the parties to the conflict involved, have led to a significant increase in the number of delegates killed in their missions since around 1990, and the ICRC's authority has since come under increasing threat. Primarily due to the dissolution of the former socialist states of the Soviet Union, the ČSSR and Yugoslavia after 1990, the number of contracting parties to the Geneva Conventions and their additional protocols rose sharply as a result of the accession of their successor states. In the ten years from 1990 to 2000 alone, 27 countries acceded to the Conventions, 18 of which were former constituent republics of Eastern European states.

In March 1992, the International Humanitarian Fact-Finding Commission, based on Article 90 of the First Additional Protocol, was constituted as a permanent body. With the beginning of the 1990s, the view began to prevail within the international community that serious violations of international humanitarian law constitute a direct threat to international peace and can therefore justify intervention under Chapter 7 of the UN Charter. This was reflected in several UN Security Council resolutions, for example Resolution 770 in 1992 in relation to Bosnia-Herzegovina and Resolution 794 in relation to Somalia, and Resolution 929 in 1994 in relation to Rwanda. An important addition to international humanitarian law was the adoption of the Rome Statute for the International Criminal Court in The Hague in 1998 and the entry into force of this agreement four years later. This created, for the first time, a permanent international institution that can, under certain circumstances, prosecute serious violations of international humanitarian law.

In the course of the US military operations in Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (since 2003), there has been repeated criticism of the US government's failure to comply with the Geneva Conventions, particularly in its treatment of prisoners in the Camp X-Ray detention facility at the US military base at Guantánamo Bay in Cuba. According to the legal opinion of the US government, the prisoners from the ranks of the Taliban and Al-Qaeda interned there are "unlawful combatants" and thus not prisoners of war in the sense of Geneva Convention III. However, the term "unlawful combatants" is only recognized by a few countries worldwide as part of military law and the law of war. Moreover, the United States has not yet complied with the obligation arising from Article 5 of Geneva Convention III to conduct a competent tribunal to decide on prisoner-of-war status on a case-by-case basis. Similarly, it has not yet been clarified which prisoners would be protected under Geneva Convention IV if Geneva Convention III were inapplicable, and to what extent its provisions are fully respected. Repeated allegations by released prisoners regarding serious violations of the rules of both conventions have not yet been publicly confirmed by an independent institution.

Following the United StatesSupreme Court decision in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld on 29 June 2006, US Deputy Secretary of Defense Gordon R. England announced in a memorandum dated 7 July 2006 that all US Army prisoners from the war on terror were to be treated strictly in accordance with the rules of Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions. This applies - in addition to the approximately 450 prisoners still held at Guantánamo Bay at that time - also to around 550 prisoners in other prisons, whose existence was thus explicitly confirmed for the first time by the authorities of the United States.

Third Additional Protocol of 2005 and Red Crystal

The controversy surrounding the Red Star of David, used by the Israeli society Magen David Adom instead of the Red Cross or Red Crescent, led to consideration of the introduction of an additional protective symbol, following an article published in 1992 by the then ICRC President Cornelio Sommaruga. It should be free of any actual or perceived national or religious significance. In addition to the debate over the Magen David Adom symbol, such a symbol is also relevant, for example, to the National Societies of Kazakhstan and Eritrea, which are seeking to use a combination of the Red Cross and the Red Crescent due to the demographic composition of the population in their home countries.

The introduction of a new sign of protection through the adoption of a third additional protocol was originally to have been realized as early as 2000 within the framework of a diplomatic conference of all signatory states to the Geneva Conventions. However, the conference was cancelled at short notice due to the start of the Second Intifada in the Palestinian territories. In 2005, the Swiss government again invited the signatory states of the Geneva Conventions to such a conference. It was originally scheduled to take place on December 5 and 6, but was then extended to December 7. After Magen David Adom signed an agreement with the Palestinian Red Crescent a few days before the conference, recognizing the latter's jurisdiction in the Palestinian territories and regulating cooperation between the two organizations, Syria demanded a similar agreement during the conference for its National Red Crescent Society's access to the Golan Heights. However, despite intensive negotiations and a compromise offer by the ICRC to Syria to establish a hospital in the Golan under ICRC supervision, no such agreement was reached.

The third Additional Protocol was therefore adopted, contrary to previous practice, not by consensus, but after a vote with the necessary two-thirds majority. Of the states present, 98 voted in favour of the protocol, 27 against and ten abstained. The official name for the new symbol is "Sign of the Third Additional Protocol"; as a colloquial term, the ICRC favours the name "Red Crystal". Along with 25 other countries, Switzerland and Austria signed the Protocol on the day of its adoption, Germany on 13 March 2006. The first ratification took place on 13 June 2006 by Norway, the second on 14 July 2006 by Switzerland. The Protocol thus entered into force six months after the second ratification on 14 January 2007. Austria became a Party on 3 June 2009, Germany on 17 June 2009.

Period of validity of older versions

Compared with the first convention of 1864, which had ten articles, the body of treaties that exists today, consisting of the four conventions and their three additional protocols, comprises over 600 articles. Even after new versions of existing conventions were signed, the old versions remained in force until all parties to the old version had signed a newer version. Therefore, for example, the 1864 Geneva Convention remained in force until 1966, when South Korea became a party to the 1949 Geneva Conventions in succession to the Republic of Korea. The 1906 version remained in force until Costa Rica signed the 1949 version in 1970. For the same reason, the two 1929 Geneva Conventions remained in force until 2006, when the 1949 Conventions achieved universal acceptance with the accession of Montenegro.

The Hague Conventions II and IV are still in force today in formal legal terms. In addition, the Hague Land Warfare Convention is also regarded as customary international law, i.e. generally applicable international law. This means that it also applies to states that have not explicitly signed this convention, a legal view that was affirmed, among other things, by a judgment of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg in 1946.

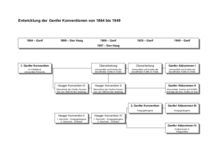

Development of the Geneva Conventions from 1864 to 1949

The Third Additional Protocol's protective symbol, also known as the "red crystal".

Logo of the International Criminal Court

A U.S. Army medic kneels next to a wounded German soldier during the invasion of Normandy, 1944.

Red lion with red sun, trademark since 1929

The Red Crescent, symbol of protection since 1929

Title page of a publication by Clara Barton from 1878

Henry Dunant

The Red Cross, a symbol of protection since 1864

Important provisions

Common Article 3

The text of common article 3, which is found with identical wording in all four conventions, reads:

In the event of an armed conflict which is not international in character and which arises in the territory of one of the High Contracting Parties, each of the Parties to the conflict shall be required to apply at least the following provisions:

1. persons not taking direct part in hostilities, including members of the armed forces who have laid down their arms and persons who have been put out of action as a result of sickness, wounding, capture or any other cause, shall in all circumstances be treated with humanity, without any discrimination on grounds of race, colour, religion or creed, sex, birth or property, or for any similar reason. For this purpose, with respect to the above-mentioned persons, are and shall be prohibited at all times and places:

a. Attacks on life and limb, namely murder of any kind, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture;

b. Capture of hostages;

c. Impairment of personal dignity, namely humiliating and degrading treatment;

d. Convictions and executions without prior judgment by a duly constituted tribunal providing the legal safeguards recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.

2. the wounded and sick are to be sheltered and cared for.

An impartial humanitarian organization, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross, can offer its services to the parties involved in the conflict.

The Parties to the conflict shall, on the other hand, endeavour by special agreements to give effect, in whole or in part, to the other provisions of this Agreement.

The application of the above provisions shall not affect the legal status of the parties to the dispute.

The principle mentioned in point 1 of this article illustrates on the one hand the common spirit of the four conventions. In this sense, it can be briefly summarized as "Be human even in war". From a legal point of view, however, Article 3 primarily represents the minimum consensus of humanitarian obligation for non-international armed conflicts, as is clear from the first sentence of the article. Until the adoption of Additional Protocol II, this article was thus the only provision in the Geneva Conventions that explicitly referred to internal armed conflicts. Article 3 was therefore sometimes regarded as a "mini-convention" or "convention within a convention". It also applies in a non-international conflict to non-state parties to the conflict, such as liberation movements, which cannot be parties to the Geneva Conventions because of their conception as treaties under international law. In addition, Article 3 also obliges states to certain minimum standards in dealing with their nationals in the event of an internal armed conflict. It thus touches on an area of law that was traditionally regulated by national law alone. The concept of human rights, which had only begun to take on a universal dimension with the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by the UN General Assembly on 10 December 1948, thus also became a component of international humanitarian law. The aspect of human rights within international humanitarian law was further expanded by Additional Protocol I of 1977, which in Articles 9 and 75 expressly prescribes the equal treatment of war victims without any adverse distinction based on race, colour, sex, language, religion or belief, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status, or any other similar distinguishing characteristic.

Other common rules

Article 2, with identical wording in all four conventions, defines the situations in which the conventions apply, firstly "...in all cases of declared war or any other armed conflict [...] arising between two or more of the High Contracting Parties" and secondly "...including in the case of total or partial occupation of the territory of a High Contracting Party". Moreover, it explicitly excludes a limitation of validity in the event that a power involved in the conflict is not a party to the treaty, comparable to the all-participation clause in force from 1906 to 1929. Article 4 of each agreement defines the persons protected in each case.

Among the provisions that already apply in peacetime is the obligation for signatory States to ensure the widest possible dissemination of knowledge of the Geneva Conventions among both armed forces and civilians (Articles 47, 48, 127 and 144 of Geneva Conventions I, II, III and IV respectively, and Articles 83 and 19 and 7 of Additional Protocols I, II and III respectively). In addition, the Parties undertake to criminalize, through appropriate national legislation, serious violations of international humanitarian law (Articles 49, 50, 129 and 146 of Geneva Conventions I, II, III and IV respectively, and Article 86 of Additional Protocol I).

The Geneva Conventions may be denounced by a contracting party (Articles 63, 62, 142 and 158 of the Geneva Conventions I, II, III and IV and Articles 99, 25 and 14 of the Additional Protocols I, II and III). It shall be notified in writing to the Swiss Federal Council, which shall inform all the other Contracting Parties. The denunciation shall take effect one year after notification, unless the denouncing Party is involved in a conflict. In this case, the denunciation is ineffective until the end of the conflict and the fulfilment of all obligations arising from the agreements for the denouncing party. Moreover, the four Geneva Conventions contain in the aforementioned articles a reference to the validity of the principles formulated in Martens' clause even in the case of a denunciation. In the history of the Geneva Conventions to date, however, no state has ever made use of the possibility of denunciation.

Geneva Convention I

Geneva Convention of 12 August 1949 for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field

Injured and sick members of the armed forces are to be protected and cared for indiscriminately by each party to the conflict (Article 12). In particular, their killing, use of force, torture and medical experiments are strictly prohibited. Personal details of injured or ill members of the opposing side must be registered and handed over to an international institution such as the ICRC's Prisoners of War Agency (Article 16).

Attacks on medical facilities, such as military hospitals and clinics, which are protected by one of the symbols of the Convention are strictly prohibited (Articles 19 to 23), as are attacks on hospital ships from land. The same applies to attacks on persons exclusively charged with the search, rescue, transport and treatment of injured persons (Article 24), as well as to members of the recognized national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and other relief organizations recognized by their governments and operating by analogy (Article 26). In Germany, in addition to the German Red Cross as a national Red Cross society, the Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe and the Malteser Hilfsdienst are also recognised as voluntary aid societies under Article 26. The persons designated in Articles 24 and 26 are to be kept in custody, if captured, only as long as the care of prisoners of war makes it necessary, and otherwise to be released immediately (Article 28). In such a case they shall be under the full protection of Geneva Convention III, but without themselves being classified as prisoners of war. In particular, they may not be called upon to perform activities other than their medical and religious duties. Transports of wounded and sick soldiers are subject to the same protection as fixed medical facilities (Article 35).

The Red Cross on a white background is established as the protective emblem within the meaning of this Convention, as a colour inversion of the Swiss national flag (Article 38). Other equal protection signs are the Red Crescent on a white background and the Red Lion with a red sun on a white background. These protective signs are to be used by authorised institutions, vehicles and persons as flags, fixed markings or armbands.

Geneva Convention II

Geneva Convention of 12 August 1949 for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked of Armed Forces at Sea

The provisions of Geneva Convention II are closely based on those of Geneva Convention I, not least because of its origins. Nevertheless, with regard to applicability, a clear distinction is made between members of the land and naval forces (Article 4). However, members of the naval forces who have reached land, regardless of the reasons, are immediately protected under Geneva Convention I (also Article 4).

The protective provisions for sick, wounded and shipwrecked members of the armed naval forces are formulated analogously to the provisions of Geneva Convention I, including the obligation to provide indiscriminate assistance and care (Article 12) and to register and transmit the data to an international institution (Article 19). The term "shipwrecked" also includes members of all branches of the armed forces if they have made an emergency landing on the water with or from an aircraft (Article 12).

The parties to the conflict may request the assistance of ships of neutral parties, as well as any other accessible ships, in taking over, transporting and caring for the sick, wounded and shipwrecked soldiers (Article 21). All ships complying with this request are under special protection. Specially equipped hospital ships, whose sole purpose is to render assistance to the said persons, shall under no circumstances be attacked or occupied (Article 22). The names and other identifying information of such ships shall be communicated to the other side at least ten days before they are put into service. Attacks from the sea on installations protected under Geneva Convention I are prohibited (Article 23). The same applies to fixed installations on the coast which are used exclusively by hospital ships for the performance of their duties (Article 27). Hospital ships in a port which falls into the hands of the opposing side must be granted free passage out of that port (Article 29). Hospital ships may under no circumstances be used for military purposes (Article 30). This includes possible obstruction of troop transports. All communications from hospital ships must be unencrypted (Article 34).

For the personnel of hospital ships, protection provisions analogous to those for the personnel of medical service facilities on land, as laid down in Geneva Convention I, apply. The same applies to ships used to transport wounded and sick soldiers (Article 38). Protected facilities, ships and persons are marked with the protective signs as laid down in Geneva Convention I (Article 41). The outer hull of hospital ships is to be completely white, with large dark red crosses on both sides as well as on the deck surface (Article 43). They should also fly both a Red Cross flag and the national flag of their party to the conflict in a clearly visible manner.

Geneva Convention III

Geneva Convention of 12 August 1949 Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War

Important for the applicability of Geneva Convention III is the definition of the term "Prisoner of War" (POW) in Article 4. Accordingly, prisoners of war are all persons who have fallen into the hands of the opposing side and who belong to one of the following groups:

- members of the armed forces of a Party to the conflict, as well as members of militias and volunteer units, provided that they are part of the armed forces, or naval units.

- Members of other militias and volunteer units, including armed resistance groups, belonging to a Party to the conflict, provided that they are under the unified command of a responsible person, can be identified by a distinctive mark recognizable from a distance, carry their weapons openly and conduct themselves in accordance with the rules of the law of war.

- Members of other regular armed forces under the control of a government or institution not recognised by the capturing Party.

- Persons accompanying the armed forces without themselves belonging to them, including civilian members of the crew of military aircraft, war correspondents and employees of companies contracted to supply the armed forces or similar services.

- members of the crews of merchant ships and civil aircraft of the parties to the conflict, unless they enjoy more extensive protection under other international provisions.

- Inhabitants of unoccupied territories who, without organizing themselves into regular units, have spontaneously offered armed resistance upon the arrival of the opposing side, if they carry their weapons openly and conduct themselves in accordance with the rules of the law of war.

In the event of uncertainty as to the status of a captured person, that person shall be treated in accordance with the provisions of Geneva Convention III until the status has been resolved by a competent tribunal (Article 5).

Prisoners of war shall be treated humanely under all circumstances (Article 13). In particular, their killing, any endangering of their health, use of force, torture, mutilation, medical experiments, threats, insults, humiliation and public display, as well as reprisals and retaliation are strictly prohibited. The life, physical integrity and honour of prisoners of war shall be protected in all circumstances (Article 14). Prisoners of war are only obliged to give their surname and first name, their rank, their date of birth and their identification number or equivalent information during interrogations (Article 17). The parties to the conflict are obliged to provide prisoners of war with an identity document. Items in the personal possession of prisoners of war, including badges of rank and protective equipment such as helmets and gas masks, but not weapons, and other military equipment and documents, may not be confiscated (Article 18). Prisoners of war shall be housed as soon as possible at a sufficient distance from the combat zone (Article 19).

The accommodation of prisoners of war in closed camps is permitted, provided that this is done under hygienic conditions that do not endanger health (Articles 21 and 22). The conditions of the accommodation must be comparable to the accommodation of the troops of the capturing party in the same area (Article 25). Separate accommodation must be provided for women. The provision of food and clothing must be adequate in quantity and quality and shall take into account individual needs of the prisoners as far as possible (Articles 26 and 27). Prisoner of war camps shall be provided with adequate medical facilities and personnel (Article 30). Prisoners of war with medical training may be used for appropriate activities (Article 32). Persons with special religious powers are to be granted freedom to carry out their activities at any time; they are further to be exempted from all other activities (Articles 35 and 36). Canteens (Article 28), religious facilities (Article 34) and facilities for sports activities (Article 38) shall be provided.

Prisoners of war of lower ranks are obliged to show due respect to officers of the capturing party (Article 39). Officers among the prisoners are obliged to do so only to higher-ranking officers and, regardless of rank, to the camp commander. The text of Geneva Convention III shall be made available in a place accessible at all times to each prisoner in his native language (Article 41). All prisoners are to be treated according to their rank and age in accordance with military customs (Article 44). Prisoners of war of lower ranks may be required to work, according to their age and physical condition (Article 49), but non-commissioned officers may only be required to perform non-physical work. Officers are not required to work, but they must be given the opportunity to do so if they so desire. Permitted activities include camp construction and repair work, agricultural work, manual work, trade, artistic pursuits, and other service and administrative activities (Article 50). None of these activities may be of military benefit to the capturing party or, unless a prisoner gives his consent, dangerous or injurious to health. Working conditions shall be comparable to those of the civilian population in the same area (Article 53), and prisoners shall be adequately remunerated for their work (Articles 54 and 62).

Prisoners of war are to be granted a monthly payment by the capturing party which, depending on rank, is to be equivalent to an amount in national currency worth eight Swiss francs for soldiers of lower ranks, twelve francs for non-commissioned officers and between 50 and 75 francs for officers of various ranks (Article 60). Prisoners of war are to be allowed to receive and send letter post and to receive money and goods consignments. Prisoners of war may elect representatives to represent them before the authorities of the capturing party (Article 79). Prisoners of war are fully subject to the military law of the capturing party (Article 82) and are equal to members of the opposite side with regard to their rights in legal matters. Collective punishment and corporal punishment are prohibited as sanctions (Article 87). Punishments for successful escape attempts, if recaptured, are inadmissible (Article 91). An escape attempt is considered successful if a soldier has reached his own forces or those of an allied party or has left the territory controlled by the opposing side.

Seriously wounded or seriously or terminally ill prisoners of war shall, if possible, be repatriated before the end of the conflict, if their condition and the circumstances of the conflict permit (Article 109). All other prisoners are to be released immediately after the end of hostilities (Article 118). In order to exchange information between the parties to the conflict, they are obliged to establish an information office (Article 122). In a neutral country, a central agency for prisoners of war must also be established (Article 123). The ICRC may propose to the parties to the conflict that they take over the organization of such an agency. The national information offices and the central agency are to be exempt from postal charges (Article 124).

Geneva Convention IV

Geneva Convention of 12 August 1949 relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War

The provisions of Geneva Convention IV apply to all persons who, whatever the circumstances, fall into the hands of a Party to the conflict or occupying power in the event of armed conflict, of which they are not themselves nationals (Article 4). Nationals of States not party to the Geneva Conventions and nationals of neutral and allied States are exempt if their country of origin maintains diplomatic relations with the country in whose hands they are. Furthermore, Geneva Convention IV does not apply to persons who are protected by one of the other three Geneva Conventions. Persons guilty of, or suspected of, acts of hostility, espionage or sabotage are not entitled to the full protection of Geneva IV if this would prejudice the security of the opposing side. They shall, however, be treated humanely in all circumstances. As soon as the security situation permits, they shall be accorded all the rights and privileges resulting from the Agreement.

Civilian hospitals may not be attacked under any circumstances (Article 18). In addition, they must be marked with one of the protective signs of Geneva Convention I. Likewise, persons who work exclusively or regularly in hospitals as medical and administrative personnel are specially protected (Article 20). The same applies to the transport of injured and sick civilians by road and rail vehicles, ships and aircraft if they are marked with one of the protective signs (Articles 21 and 22). Parties are required to ensure that children younger than 15 years of age who are permanently or temporarily without the protection of their families are not left to fend for themselves (Article 24). Where possible, these children should be cared for in a neutral country for the duration of the conflict.

Persons protected under Geneva Convention IV are entitled in all circumstances to respect for their person, honour, family ties, religious beliefs and customs and other habits (Article 27). They shall be treated humanely without distinction in all circumstances and protected from violence, threats, insults, humiliation and public curiosity. Women shall be afforded special protection against rape, forced prostitution and other indecent assaults against their person. However, the presence of a protected person does not mean that a particular place is protected from military operations (Article 28). Torture and extortion of protected persons for the purpose of obtaining information is unlawful (Article 31). Looting, reprisals and hostage-taking are prohibited (Articles 33 and 34).

Protected persons have the right to leave the country where they are as long as this does not harm the security interests of the country (Article 35). The security and care of protected persons during their departure shall be provided by the country of destination or the country of nationality of the persons departing (Article 36). Protected persons shall, as far as possible, receive medical care from the country in which they are located at a level comparable to the inhabitants of that country (Article 38). Internment of protected persons or their placement in assigned areas is permitted only when absolutely necessary for the security of the country concerned (Article 42). Internment for protection, at the request of the persons concerned, should be carried out if the security situation so requires. The extradition of protected persons to States not party to Geneva Convention IV is inadmissible (Article 45).

The right to leave under Article 35 also applies to residents of occupied territories (Article 48). Expulsion or deportation from an occupied territory against the will of the protected persons concerned is inadmissible, irrespective of the reason (Article 49), as is the relocation of civilians who are nationals of an occupying power to the territory of an occupied territory. Residents of an occupied territory may not be compelled to serve in the armed forces of the occupying power. The destruction of civilian facilities and private property in occupied territory is prohibited unless it is part of necessary military operations (Article 53). The Occupying Power is obliged to ensure the supply of food and medical articles to the population of the occupied territory and, if it finds itself unable to do so, shall allow relief supplies to be delivered (Articles 55 and 59). The activities of the respective national Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies and similar relief organizations may not be restricted by the occupying power (Article 63). In Germany, recognition under Article 63 applies not only to the organizations already mentioned in Geneva Convention I but also to the Arbeiter-Samariter-Bund, the Deutsche Lebens-Rettungs-Gesellschaft e. V., the Technische Hilfswerk and the fire brigades. The criminal law of the occupied territory is to remain in force unless this constitutes a danger to the security of the occupying power or an obstacle to the implementation of Geneva Convention IV (Article 64).

Similar rules apply to the internment of protected persons as to the accommodation of prisoners of war (Articles 83, 85-94). However, protected persons within the meaning of this Convention are to be accommodated separately from prisoners of war (Article 84). Educational opportunities must be ensured for children and adolescents. Protected persons may be required to work only at their own request (Article 95). An exception to this is persons with medical training. Personal property of interned protected persons may be confiscated by the occupying power only in exceptional cases (Article 97). Interned persons may elect a committee to represent them in dealings with the authorities of the occupying power (Article 102). They shall also be granted the right to receive and send letter post and to receive parcels (Articles 107 and 108).

Crimes committed by internees are governed by the law of the territory in which they are located (Article 117). Internment must be terminated when the reasons for internment no longer exist, but at the latest as soon as possible after the end of the armed conflict (Articles 132 and 133). The costs of repatriation are to be borne by the interning party (Article 135). In analogy to Geneva Convention III, information offices and a central agency for the exchange of information are to be set up by all parties to the conflict (Articles 136-141).

Additional Protocol I

Protocol of 8 June 1977 Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts

Additional Protocol I supplements the provisions of the 1949 versions of the four Geneva Conventions. It therefore refers in Article 1 to the common Article 2 of the four Geneva Conventions as regards its scope. Paragraph 4 of Article 1 further supplements the scope of Additional Protocol I to include armed conflicts in which peoples are fighting against colonial rule and foreign occupation and against racist regimes in the exercise of their right to self-determination, based on relevant contents of the Charter of the United Nations. In order to monitor the application of and compliance with the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I, Article 5 introduces the so-called system of protecting powers, i.e. the designation of one protecting power by each of the parties to the conflict, and empowers the ICRC to mediate in the search for protecting powers accepted by all parties to the conflict. In addition, the ICRC and other neutral and impartial humanitarian organizations are given the opportunity to act as a substitute protecting power.

Part II of Additional Protocol I contains provisions on the protection of the wounded, sick and shipwrecked. The definitions contained in Article 8 do not distinguish between military and civilian personnel. These persons are to be spared and protected, treated humanely and given medical treatment, care and nursing according to their needs (Article 10). Articles 12 to 15 extend the protection of medical units to civilian units as well and define corresponding rules and restrictions. Article 17 contains provisions on the participation of civilians in relief operations. Hospital ships and other watercraft used in accordance with Geneva Convention II are, according to Additional Protocol I, also protected under this Convention when transporting wounded, sick and shipwrecked civilians (Article 22). Articles 24 to 31 contain provisions on the use and protection of air ambulances. Measures for the exchange of information on missing persons and the handling of mortal remains are defined in more detail in Articles 32 to 34.

Part III contains provisions on methods and means of warfare. Article 35 restricts the parties to the conflict in their choice of these methods and means and contains in particular a prohibition of material and methods "which are likely to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering" or which are "intended to cause, or may be expected to cause, extensive, prolonged and severe damage to the natural environment". The prohibition of insidiousness contained in Article 37 derives from similar provisions contained earlier in the Hague Conventions, as does the prohibition of the order not to leave anyone alive (Article 40). Attacks against an enemy who is out of action are strictly prohibited (Article 41). This includes soldiers who have either surrendered, are wounded or have been captured. Articles 43 to 45 contain provisions defining combatants and prisoners of war. This excludes mercenaries (Article 47).

Part IV contains supplementary rules for the protection of the civilian population. Article 48 lays down the principle that a distinction must always be made between the civilian population and combatants and that acts of war may only be directed against military targets. Indiscriminate attacks are prohibited (Article 51). Article 53 contains basic rules for the protection of cultural property and sites, and Article 55 contains corresponding rules for the protection of the natural environment. Attacks against installations or facilities containing dangerous forces (dams, dykes and nuclear power plants) are prohibited if such an attack is likely to cause heavy casualties among the civilian population (Article 56). This prohibition also applies when these facilities constitute military targets. In addition, a sign consisting of three orange circles arranged in a row is defined to identify corresponding installations. Article 57 establishes precautionary measures to protect the civilian population when planning an attack. Undefended places and recognized demilitarized zones may not be attacked (Articles 59 & 60). Articles 61 to 67 contain rules on civilian protection. For example, Article 66 defines an international protective mark to identify the personnel, buildings and material of civil defence organisations, consisting of a blue triangle on an orange background. Articles 68 to 71 define aid measures for the benefit of the civilian population.

Articles 72 to 79 supplement the provisions of Geneva Convention IV on the protection of civilians in the power of a party to the conflict. Refugees and stateless persons are now protected accordingly (Article 73), as are journalists (Article 79). Articles 80 to 84 define implementing provisions for the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol I. Article 81 is dedicated explicitly to the protection of civilians. Article 81 is explicitly devoted to the activities of the Red Cross and other humanitarian organizations. Regulations on the punishment of violations of the Geneva Conventions and the Additional Protocol are contained in Articles 85 to 91. Of particular importance is the establishment of an International Commission of Inquiry (Article 90).

The final provisions of Additional Protocol I, such as rules on entry into force, accession, amendments and denunciation, are contained in Articles 92 to 102. Annex I defines identity cards, protective and identification markings and light and radio signals used as identification signals for various applications.

Additional Protocol II

Protocol of 8 June 1977 Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts

Additional Protocol II defines rules for all armed conflicts that are not covered by Article 1 of Additional Protocol I. These are conflicts that take place on the territory of a Party to the Additional Protocol between its regular armed forces and renegade armed forces or other organised armed groups (Article 1). These are conflicts that take place on the territory of a Party to the Additional Protocol between its regular armed forces and renegade armed forces or other organised armed groups (Article 1).

Part II defines basic rules for humane treatment. All persons who are not directly or no longer taking part in hostilities are entitled to respect for their person, honour and convictions and are to be treated with humanity in all circumstances. The order not to leave anyone alive is prohibited (Article 4). Explicitly prohibited are in particular attacks on the life, health and well-being of these persons, especially intentional killing and torture. Article 6 regulates the prosecution of crimes related to the armed conflict. Part III contains provisions on the treatment of the wounded, sick and shipwrecked. These are similar to the corresponding rules of Additional Protocol I (Articles 7 and 8), also with regard to the protection of medical personnel and corresponding means of transport (Articles 9 to 12). Part IV defines regulations for the protection of the civilian population. Again, these regulations are similar to those of Additional Protocol I, including the protection of installations and facilities containing dangerous forces (Article 15) and the protection of cultural property and sites (Article 16).

The final provisions of Additional Protocol II, such as those on circulation, accession and entry into force, amendments and denunciation, are contained in Part V.

Additional Protocol III

Additional Protocol of 8 December 2005 to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 on the Adoption of an Additional Safeguard Document

The sole objective in adopting Additional Protocol III was to introduce a new protective symbol in addition to the symbols of the Red Cross, Red Crescent and Red Lion with Red Sun already defined by the Geneva Conventions.

Under Article 2, the new sign has the same status as the three existing signs. It takes the form of a square red frame on a white background. An illustration of the sign is given in the Annex to Additional Protocol III. The conditions for the use of this sign are the same as for the three existing signs, in accordance with the provisions of the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and the two Additional Protocols of 1977. The Contracting Parties may at any time use, even temporarily, a sign different from their customary protective sign if this increases the protective effect. Article 3 regulates the use of the new sign as a distinctive sign (for indicative purposes). For this purpose, either one of the three existing protection signs or a combination of these signs may be used inside the sign. In addition, signs which have been effectively used by a Contracting Party and whose use was communicated to the depositary State before the entry into force of Additional Protocol III may also be used within the new sign.

Article 4 contains provisions on the use of the new protective sign by the International Committee of the Red Cross and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. In accordance with Article 5, medical and chaplaincy personnel of missions under United Nations supervision may also use one of the three existing marks or the new mark. Article 6 obliges the Parties to prevent the misuse of the new protective sign. Articles 7 to 14 contain the final provisions of Additional Protocol III.

The International Civil Defence Mark

The mark used to identify installations and equipment containing dangerous forces

.jpg)

Manzanar War Relocation Center for the internment of Japanese-born civilians in the United States during World War II, c. 1943.

.jpg)

Prisoners of war in Aachen, 1944

Hospital ship USNS Mercy of the US Navy

Red Cross train with wounded French soldiers, 1917

Questions and Answers

Q: What are the Geneva Conventions?

A: The Geneva Conventions are a set of four treaties of international law at wartime.

Q: Where were the Geneva Conventions formulated?

A: The Geneva Conventions were formulated in Geneva, Switzerland.

Q: What were the Geneva Conventions created for?

A: The Geneva Conventions were created for humanitarian issues.

Q: Who started the creation of the Geneva Conventions?

A: The Swiss Henri Dunant was the person who started the creation of the Geneva Conventions.

Q: Why did Henri Dunant start the creation of the Geneva Conventions?

A: Henri Dunant started the creation of the Geneva Conventions after he saw the unimaginable cruelty of the Battle of Solferino in 1859.

Q: What do some parts of the Geneva Conventions say?

A: Some parts of the Geneva Conventions say that all countries who signed must create national laws to make violations of the Geneva Conventions a crime.

Q: How many Geneva Conventions are there?

A: There are four Geneva Conventions.

Search within the encyclopedia