Anabaptism

![]()

This article describes the movement that arose during the Reformation. For churches with believers' baptism, see Baptist sects; for groups of early Christianity, see Anabaptist sects.

Anabaptists (formerly also called rebaptizers or anabaptists) are followers of a radical Reformation Christian movement that arose after 1520 in the German- and Dutch-speaking parts of Europe and is counted among the left wing of the Reformation.

Anabaptism is usually perceived in the German-speaking world as a historical phenomenon of the Reformation period, for apart from the Mennonites, Anabaptists have disappeared from the German-speaking world as a result of persecution and pressure to assimilate. But Anabaptist churches today have a worldwide following numbering in the millions, with traditional Anabaptist groups such as the Amish, Old Colony Mennonites, Old Order Mennonites, and Hutterites among the fastest growing Christian communities.

Important concepts of the Anabaptists are the following of Christ, the church as brotherhood and non-violence. They based their thinking and behavior entirely on the literal interpretation of the New Testament (sola scriptura), which is also expressed in their understanding of the sacraments (believers' baptism, the Lord's Supper). In addition, there are demands for freedom of faith, for separation of church and state, partly for community of goods (Hutterites) and for separation from the world. The above-mentioned concepts and religious attitudes or practices are differently pronounced and accentuated in the individual groups of the Anabaptist movement. On the whole, the Anabaptist movement was subject to intense persecution by the authorities and the official churches, especially in the first two centuries of its existence.

Today's Anabaptists are the Mennonites, the Amish, and the Hutterites. Among the younger currents in Anabaptism are the pietistic Anabaptist Mennonite Brethren congregations and the Bruderhöfer. Anabaptists in the broader sense include the Schwarzenau Brethren, the Bund Evangelischer Täufergemeinden (ETG, also Evangelically Baptized or Neutäufer), and the River Brethren. Although there are also individual points of contact with later free churches such as the Baptists, these are not to be counted as Anabaptists in the confessional sense.

Mennonite church in Friedrichstadt/Schleswig-Holstein

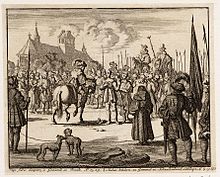

The Anabaptist Dirk Willems saves his pursuer. As a result, he himself can no longer escape and is burned to death. Picture by Jan Luyken (1685)

Origin

In older Anabaptist research, the origin of the Anabaptist movement was assumed to be monogenetic. According to this, the Anabaptist movement would have had its sole beginning in the Reformation city of Zurich among former companions of Huldrych Zwingli such as Konrad Grebel, Felix Manz and Jörg Blaurock, and would have spread from there along various paths, first in Switzerland and then in southern Germany and Austria, and later also in the Dutch and northern German regions. After 1960 the idea of a polygenesis prevailed, according to which three main roots of Anabaptism can be identified:

- in the Zurich Reformation with Grebel, Manz and Balthasar Hubmaier

- in the radical Reformation around Karlstadt and Thomas Müntzer with the apocalyptic Hans Hut in Upper Germany (cf. e.g. also the role of the Zwickau prophets)

- in the spiritualistic-temporal milieu of Strasbourg, from where Anabaptism was brought to the Lower German region via Melchior Hofmann.

In the meantime, the polygenetic approach has also been further developed in some points, for example, by again emphasizing and researching the relationships and interactions of the individual groups with one another. Accordingly, the beginning of the Anabaptist movement, beginning with publicly disseminated criticism of infant baptism, can be placed at 1521, similarly to the beginning of the Reformation, which is placed at 1517, without Reformation concerns already being implemented in that year. In both cases, however, a movement was set in motion that gradually led to visible consequences in the following years.

Within a few years, the Anabaptist movement developed into an important Central European branch of the Reformation, despite massive state and church persecution. The preconditions of all Anabaptist groups were similar: those referred to as "radical reformers" were disappointed with the progress of the Reformation. They demanded the "immediate establishment of a state-free Protestant church according to the model of the New Testament". Their ideal was a free church on the Original Christian model, a "community of believers" based on the free will of individual church members. Therefore, they rejected infant baptism, for which they understood there was no evidence in the New Testament Scriptures. They baptized only those who personally desired baptism and accepted into their congregations only people who had been baptized as believers. Other central aspects of the Anabaptist movement included congregational autonomy, the priesthood of all believers, the refusal to take oaths, and the symbolic understanding of the Lord's Supper. Social aspects also played a role. However, the characteristics of the various Anabaptist groups can by no means be described as uniform.

→ Main article: Radical Reformation

Radical beginnings in Zurich

An important branch of the Anabaptist movement arose in Zurich, first as an ally, later as a split from the Reformation initiated and carried out there by Zwingli: the so-called "founding fathers" of the Anabaptist movement around Zwingli did not think his reform of the church went far enough. They belonged to the circle of Bible readers around Andreas Castelberger. These proto-Anabaptists acted as catalysts for the Zwinglian Reformation. They made their presence felt with radical actions such as breaking fasts, disrupting sermons and iconoclasm. At the same time, clergymen were active in some rural communities, demanding more radical measures and also supporting the peasants in their social demands. Particularly active were Simon Stumpf in Höngg and Wilhelm Reublin in Witikon. The question of baptism was not yet central at this time. In the course of the Second Zurich Disputation in the autumn of 1523, a break occurred between the later Anabaptists and Zwingli. A group around Simon Stumpf and Konrad Grebel felt that the Reformation process was not thoroughgoing enough. They demanded the immediate abolition of the mass and the removal of the images. Zwingli, however, wanted to leave it to the city council to determine the timing and procedure for establishing the new order.

In the spring of 1524, preachers in some rural parishes openly called for the refusal of infant baptism. The council of the city of Zurich then issued an order on August 11, 1524, to have all infants baptized: Eß soll ouch angentz die, so ungetouffte kinder habent, dieselbigen touffen lassen, und welcher dass nit tätte, der soll 1 march silber zuo buoß geben. This order was opposed by the circle around Manz and Grebel. The question of baptism now took on a central position in the dispute with Zwingli. One took up epistolary contact with other reformers such as Karlstadt and Thomas Müntzer, which was at the same time a kind of self-reflection. At the end of 1524, another attempt at understanding was made in the so-called two Tuesday conversations between Zwingli and the circle around Grebel and Manz. The talks were fruitless, so Felix Mantz wanted to put his views on baptism in writing. For this purpose he wrote the Protestation and Schutzschrift, a letter of defense to the city council. Mantz defended himself against the accusation of sedition and demanded a written discussion with Zwingli in which infant baptism was to be examined for its biblical justification.

On January 17, 1525, the council summoned representatives of both sides to a public disputation in the city hall of Zurich, so that both groups could justify their baptismal doctrine on the basis of Scripture. The outcome in Zwingli's favor, however, was a foregone conclusion. On January 18, the Zurich council issued a devastating mandate against the Anabaptists. All those who refused to baptize their children were ordered to have their newborn children baptized immediately. Those who did not comply within eight days would be expelled from the country. The baptismal font that had been removed from the church in Zollikon was to be put up again immediately. In a second mandate of January 21, 1525, the verdict was tightened even more. Grebel and Mantz were forbidden any further agitation against infant baptism, and teaching in their Bible schools (special schools) was forbidden, which amounted to a de facto ban on meetings of the opponents of infant baptism. The non-Christians among the Anabaptists (among them: Reublin, Brötli, Castelberger, and Hätzer; Simon Stumpf had been expelled earlier) were ordered to leave the territory of Zurich within eight days. The decision was final; further disputation was ruled out.

First communities

Grebel and Manz ignored the ban and continued to gather their followers to study the Bible together. On the evening of January 21, 1525, Grebel's circle met at the home of Felix Manz's mother. The oldest chronicle of the Hutterite Brethren, the Great Book of History, preserves an account of the proceedings of this meeting. The chronicle reports that "fear began and came upon them" and "that their hearts were troubled." After a prayer, the former Roman Catholic priest, Jörg Blaurock, from what is now Graubünden, came before Konrad Grebel and asked him to baptize him. Grebel immediately complied with this request. Afterwards, at their request, Blaurock also baptized the others of the circle - among them Felix Manz. This baptism is still considered the founding act of the Anabaptist movement. In commemoration of this date, the Mennonite World Conference calls Anabaptist congregations to an annual World Communion Sunday around January 21.

The baptism of believers performed in the circle around Grebel and Manz did not remain secret. The repression on the part of the Zurich city council led Grebel, Manz and Blaurock to flee to Zollikon in the Zurich hinterland. Here Johannes Brötli, who had to leave Zurich after the disputation on January 17, had already taken up temporary residence and spread Anabaptist ideas among the population.

Immediately after his arrival, Jörg Blaurock began to preach in an evangelistic manner in the farms of Zollikon. Within a very short time, the preaching triggered a repentance movement among the inhabitants, as a result of which Blaurock baptized a large number of revived people. Back and forth in the houses of Zollikon the Lord's Supper was celebrated after the baptismal ceremonies in "apostolic unadornment" (Fritz Blanke). The house fathers read the New Testament communion texts in the living rooms and handed bread and wine to the participants of their house meetings. While in "Reformed" Zurich the Protestant celebration of the Lord's Supper was not approved until Easter 1525, following a council decision, the Zollikon Anabaptists had already radically separated from the Roman Catholic tradition months earlier. Having already opposed decisions of the authorities through their baptisms, they now, with their "evangelical" communion celebrations, denied the state a second time the right to decide in spiritual matters. Thus - according to Fritz Blanke - the first Protestant free church appeared in Zollikon in 1525.

→ Main article: Chronological table of the history of the Anabaptists

On January 30, 1525, the Zurich council sent city servants to Zollikon and temporarily arrested baptized and Anabaptists. While Felix Manz had to remain in prison until the fall of 1525, the Zollikon peasants as well as Grebel, Blaurock, Brötli and Wilhelm Reublin were released. Reublin went to Waldshut, where he was able to win over the town pastor Balthasar Hubmaier, who had already converted to the Lutheran Reformation, and his congregation to Anabaptism. Brötli emigrated to Hallau in the canton of Schaffhausen and founded an Anabaptist congregation there the same year. Blaurock and Grebel turned to the Zurich Oberland and gained a large following there through their preaching. The success of the missionary work increased when Felix Manz joined them after his release.

Blaurock, Grebel and Manz were arrested again. Zwingli tried to persuade them to recant in various conversations, but neither he nor the torturers succeeded in the so-called embarrassing interrogations. While Grebel and Blaurock were released with the help of influential friends, Manz remained in custody and was drowned in the Limmat in Zurich in the first days of January 1527.

The Anabaptists' sense of mission was strengthened by the persecutions, in which they saw a confirmation of their way. They continued to teach their Anabaptist ecclesiology in the Zurich countryside and "set up the sign of baptism"-both in St. Gallen and in eastern Switzerland. The Anabaptist movement also spread to Basel. Hubmaier ensured that the radical Reformation ideas were widely disseminated by publishing numerous writings. Johann Groß, a disciple of Hubmaier, proselytized as an Anabaptist messenger in the region around Bern. Reublin and Michael Sattler, who had also joined the Anabaptist movement early on and later made a name for himself as the author of the so-called Schleitheim Articles, brought Anabaptism to southwestern Germany. Jörg Blaurock initiated the founding of Anabaptist congregations in Graubünden and Tyrol.

Schleitheim article

→ Main article: Schleitheim article

After the failure of the Bauernerhebung, the Anabaptist movement lost a large part of its mass base. This, along with increasing repression from outside and confusion within, were reasons for a self-reflection that led some of the Anabaptists down the path of secession. This secession led to expulsion for the Anabaptists around Sattler and Reublin, who had found refuge in tolerant Strasbourg, in early 1527, since the Strasbourg council generally tolerated dissenting theological views-the trial of Thomas Saltzmann is an exception-but not civic disobedience such as refusing to participate in the Schanzarbeiten, to which all citizens were obligated, on the grounds that no authority could be Christian.

On February 24, 1527, a "fraternal association" of Anabaptists met in Schleitheim (near Schaffhausen) under the leadership of Michael Sattler. At this meeting, the first formulated programmatic confession of the Anabaptists was written. This document, the so-called Schleitheim Articles, lists the most important principles of Anabaptism in seven points:

- Believers' baptism (rejection of infant baptism)

- Church discipline (ban for misconduct)

- Breaking of bread (communion) as a sign of communion

- Separation from the "world

- Free choice of shepherd/chaplain

- conscientious objection

- denial of oath

With the Schleitheim Articles, the social revolutionary took a back seat to the religious component. At the same time they were an expression of a turning away from a popular church movement towards a minority free church.

The Schleitheim Articles were also the subject of the synod held in Augsburg in August 1527. However, Sattler's theses, which were defended by the Waldshut Anabaptist Jakob Gross, could not prevail here. Because many of those present at this Anabaptist synod were executed shortly afterwards, this meeting is also known as the Augsburg Martyrs' Synod.

Front page of the Schleitheim articles

Anabaptist disputation 17 January 1525 in Zurich City Hall. Depiction from the early 17th century

Felix Manz is drowned in the Limmat in 1527. (Representation from the 17th century)

Commemorative plaque of one of the first Anabaptist meetings (25 January 1525) in Zollikon

Felix Mantz: Protestation and Protective Writ to the Council of Zurich (1524/25)

Anabaptist court in Schwäbisch Gmünd 1529 Jan Luyken (1685)

Spread 1525 to 1530

After the Swiss beginnings in 1525/26, Anabaptist teachings spread "immensely rapidly" throughout Central Europe within the first five years and were perceived by many contemporary chroniclers as a third "powerful" Reformation movement-alongside Lutheran and Zwinglian. There are estimates that, after 1530, somewhat one-third each of the population in Germany was Catholic, Lutheran, and Anabaptist.

As early as the spring of 1526, Anabaptists can be traced to the Inn valley in Tyrol and, at about the same time, to the area around Horb and Rottenburg am Neckar. In Strasbourg, where reports of the refusal of infant baptism are known as early as 1524, Jörg Ziegler, who had been baptized by Reublin, founded the first Anabaptist congregation in 1526. The first traces of Anabaptists are also documented for Augsburg at this time. In the summer of the same year, Anabaptist messengers evangelized in Moravia.

The spread of Anabaptism experienced a particular upswing in 1527. Lower and Upper Austria were seized in the spring. In southern Germany, congregations were established in the course of the year in Nuremberg, Erlangen, Regensburg, Memmingen, Munich, Esslingen and Schwäbisch Gmünd. In the same year, the Anabaptist movement also began to spread to Silesia. When the Anabaptists gained a foothold in Tyrol at the end of 1527, King Ferdinand wrote to the authorities there that "such kindled fire" was to be met with all determination. In the Duchy of Württemberg, Anabaptist congregations began to appear at the beginning of 1528. In mid-1528, an Anabaptist revival occurred in Sorga, Hesse, which spread to the heartlands of the Lutheran Reformation. It is therefore not surprising that the Diet of Speyer in 1529 was intensively concerned with the growth of this movement and decided on countermeasures. The former Lutheran messenger and later apocalyptic preacher Melchior Hofmann, who came into contact with Anabaptism in Strasbourg in 1530, preached baptism in the Netherlands as a sign of the betrothal of the believing soul to God and baptized 300 people in Emden. After that, refugees carried the Anabaptist teachings to Prussia and even to England. Thousands - according to the already mentioned chronicler Sebastian Franck in 1531 - accepted baptism and covered the whole country.

Spread of the Anabaptist movement 1525-1550

Search within the encyclopedia