Fur

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Fur (disambiguation).

Fur, or also smoked fur, is the term used to describe types of fur and skins of mammals with mostly very dense hairs that are processed into clothing and accessories. Furs, pelts and fur goods have long been counted among the earliest goods in world trade. Contrary to popular belief, furs played an extremely minor role during the migration of peoples. In Europe, long-distance trade only emerged after the Carolingian period due to impulses from the Islamic world. Hunting was often carried out by members of indigenous peoples and full-time trappers. The colonial expansion of European powers in North America, northern Europe, and northern Asia was strongly motivated by the fur trade. Production, processing, and sales were organized by furriers, guilds, markets, and fairgrounds and trading companies. These were privileged and supported politically and militarily by the cities and territorial states involved. Until the late 17th century, there were decrees and dress codes in Europe that allowed some types of fur only to certain groups of people and estates.

With industrialisation, although breeding became the main source of the raw material, fur became increasingly insignificant compared to other commodity groups; this was even more true for trapping. Trade in the pelts of certain species, particularly those threatened with extinction, has been restricted or banned since the 1970s due to the Washington Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species and other requirements. Many animal rights activists, and animal rights activists in particular, also oppose the use of furs.

The most common animals kept for fur production are fox, polecat, mink, raccoon dog (sold under various names, often as "Finnraccoon"), nutria and chinchilla. In Denmark mink is the most common fur animal, in Finland fox.

The market for fur has shifted significantly to Asia since the end of the 20th century. In 2002, the total value of fur produced in the EU was € 625 million.

The (sable) cap of Monomakh, precursor of the tsar's crown (15th century)

Mink short coat, dyed, top with burned-in pattern by laser (Regensburg, 2016)

Origin of fur

Overview

→ Main article: Fur types

The origin of the furs can be divided into:

- Furs produced as a by-product of livestock farming and meat production (about 40 % of fur production)

- hides and skins of animals which are hunted independently of fur production because they are or are perceived to be pests or nuisances

- Furs of fur animals which are hunted, trapped or farmed solely for their fur.

When farm animals are slaughtered, the skins produced include those of lamb and sheep, (Persian, many different breeds of sheep), rabbit (rabbit skin), goat and kid, cow and calf, horse and foal, reindeer (or pijiki) and kangaroo (wallaby skin).

The types of use were subject to considerable historical change. Thus, individual breeds of sheep and rabbits are bred specifically for their special fur characteristics. These include, for example, the Karakul sheep (curly Persian), the Merino sheep (silky, for wool and lamb veloure), the Chinchilla and Rexkanin. Farm animals such as hamsters, guinea pigs, horses and donkeys or even dogs can in principle be considered as fur suppliers. They were and are also used as meat suppliers in some countries and cultures, depending on the food taboo. The fur supplier beaver was a popular fasting food in the Middle Ages, opossum and swamp beaver (Nutriafell) are partly still consumed today. Seals are a staple food of the Eskimos.

Wild catch still accounts for about 15 % of the global supply. Of particular importance are the furs of animals that are hunted as pests or nuisances. These include wild rabbits, hamsters, mole fur, New Zealand possum, marten, polecat, weasel, nutria, muskrat and raccoon. Certain types of traps are prohibited in the EU.

In 2008, the main share of farmed fur animals went to the mink mink, followed by sheep, silver fox, blue fox, marten dog (sea fox fur), chinchilla, nutria, sable and polecat. Depending on the fashion, more or less successful attempts were made to breed other fur-bearing animals (raccoon, muskrat, skunk, among others). Most fur animal skins come from fur farms. For reasons of animal welfare, the breeding of fur animals is prohibited in Austria, Switzerland and Great Britain.

Fur hunting and trade

Already since the 16th and 17th century, laws for the protection of various hunting animals were passed in several countries, in which certain closed seasons were specified. Since the middle of the 19th century, there have been additional efforts to preserve wildlife, which have found expression in various laws. Most notable was the North Pacific Fur Seal Convention in 1911 to protect the northern fur seal and sea otter. In 1973, the Washington Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, internationally known as CITES, was adopted and ratified by the Federal Republic of Germany in 1976. It restricts and regulates trade in wild animals and plants. Additional restrictions are imposed by the Federal Species Protection Ordinance, which came into force on 1 January 1987.

Some fur-bearing animals, such as muskrat and mink, have established themselves as neozoa in the European wild, partially displacing endogenous species such as the European mink. Captive escapes from fur farming or deliberate releases are controversial. Conservation measures include international trade agreements restricting the fur trade, as well as shooting quotas, protected areas and closed seasons for individual species. The World Wildlife Fund accepts traditional fur trapping under well-defined conditions. This hunting management as well as the management of individual wild fur-bearing species is controversial, for example in seal hunting and muskrat control. NABU-Germany accepts the utilization of the furs resulting from population-adapted fox hunting in Germany. At the latest since the Washington Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species came into force in 1973, almost all spotted cats (South American wild cats, ocelots, all big cats) and otters are no longer legally traded. This is without prejudice to the free and unrestricted trade and import of smoked products, furs and fur garments in the EU.

Fur farming

The keeping of fur animals is researched as an aspect of agriculture, zoology as well as veterinary science, the scientific monitoring of hunting and keeping of wild animals is a matter of vegetation biology as well as forestry. Knud Erik Heller of the University of Copenhagen advocates, on the basis of studies of the stress levels of fur-bearing animals, for example, a concealed retreat for caged mink, the cage size as such having little influence. The wearing properties, such as the ability to keep warm and temperature regulation with and in furs, are of great interest for behavioural research, as in the manufacture of appropriate clothing.

In most states, the keeping of fur animals falls under the general regulations on breeding as well as on the slaughter or killing of animals. Under section 4(1) of the Animal Welfare Act 1972, vertebrate animals "may be killed only under stunning or otherwise, so far as is reasonable in the circumstances, only by avoiding pain". The performance of the killing is made dependent on appropriate knowledge and skills and is followed up within the training of fur farmers by recommendations for the killing of fur animals on farms in a manner appropriate to the welfare of the animals. Wild-caught animals are subject, inter alia, to the Trapping Regulation. Cross-border trade is regulated by the international Washington Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species.

At European level, the import or export of cat and dog fur to or from EU countries was banned with effect from 31 December 2008; cat fur was used in particular to relieve rheumatic pain. The reason given for the ban is the lack of acceptance of the use of these emotionally salient pets. National regulations are in place in countries such as Switzerland and the UK, where fur farms have been banned since the early 1990s. Commercial use is no longer profitable, as costly enclosure husbandry is prescribed for these wild animals. In Austria, the Ordinance on the Keeping of Fur Animals has banned fur farming for commercial purposes since 1998. A European ban failed because of the attitude of the Scandinavians, especially Finland and Denmark, where fur farming is an important regional economic factor.

Origin labels

Since 2008, the International Fur Trade Federation, an association of fur traders, has been organising labelling of furs with the "Origin Assured" mark. Such a label is supposed to indicate that the goods come from certain animal species and from certain countries where "regulations or standards" exist for the production of the furs. For the species for which the label is issued, a distinction is sometimes made between countries of origin and wild and farmed animals, but not between farms or companies. Since 2003, there has also been a label propagated by fur producers, which is supposed to indicate that the furs are "European" (citation: German Fur Institute) furs, indicating the animal species.

_fur_skin.jpg)

Washable rheumatism house cat fur

Fur trader in Cairo, painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme (1869)

Fur Production

Quality

The quality of a coat depends on many factors. A particularly dense and hard-wearing coat is found in furry species that live entirely or temporarily in water. The colder the habitat, the denser and silkier the hair; likewise, winter pelts are of better quality than summer pelts. Furs from small carnivores have a more brisk and therefore more stable leather than those from herbivores. The highest qualities of fur come from winter pelts of marten-like small carnivores, such as the mink. In furriery, furs have hair densities of over 400 hairs per cm², skins 50-400 hairs/cm², all hair densities below this are called hairless skins.

Furs are subject to natural ageing, depending on various external influences (temperature, exposure to light, humidity, type of tanning). For the visibly decreasing beauty and freshness of the material in the course of time, there was once the paraphrase, they "bloom off".

Processing

→ Main article: Furriers

Furriers process smoked or dressed animal skins suitable for fur processing. In 2009 there were 825 companies with 6850 employees in Germany. The first guilds are already known from the 12th and 13th century. Similar to related trades such as white tanners, bag makers, glove makers and parchment makers, furriery was considered an impure trade in the Middle Ages because of the handling of dead animals, but furriers were still respected and mostly able to hold office.

In Asia, especially in Japan and India, this has resulted in discrimination that continues to this day (cf. Buraku and Dalit). There, it is not the products but the associated occupational groups and their members with their families that are considered impure.

In contrast to tanning, the preparation of raw hides and skins into leather, the raw skins are prepared into durable furskins. For this purpose, the fur is preserved in such a way that the hair remains intact. The finishing process attempts to replace perishable fats and proteins with preserving and stabilizing substances. Dried raw skins are turned into supple, hard-wearing furskins that can be processed. The furs are fleshed and the subcutaneous connective tissue is removed, the fur leather is specially tanned and greased. Finally, the furskins are stretched into a shape suitable for further processing, cleaned and smoothed. Until about 1850, furriers prepared their raw furs themselves, after which the preparation was separated from the actual furriery.

·

Cutting templates for a coat of fox, silklamm and leather

·

Cutting the leather strips (galons) in a furrier's workshop

·

The body part, sewn and stretched to the pattern

· .jpg)

The finished coat

In further processing steps known as "fur finishing", the pelts can be additionally dyed, among other things, and the leather side can be veloutated or napped. By shearing or plucking, the furs are further refined into so-called "velvet furs". As early as the early modern period, a division of labour developed in which pieceworkers and table masters were employed. Later, fur semi-manufacturers and furriers for the finished fur garments were added. There were hardly any elaborate changes in the shape of the processed furs before the 18th century. With the invention of the fur sewing machine around 1872 by Joseph Priesner (since 1888 also with a small motor), the processing of furs became much easier and the fur industry expanded considerably. After the end of the apprenticeship, there was often a specialization of the activity into the "cutting" and the "sewing furrier". For sewing with the fur sewing machine, a renewed division of labour often takes place. This concerns in particular the sewing of the so-called "outlet work", the lengthening of the skins by cutting equipment.

The centres of fur processing include certain regions in Greece and Turkey. In German-speaking countries, fur processing is small, medium-sized and very much regionally structured, with the remaining fur farms mainly in Westphalia, Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony. In the sixties and seventies, Germany (both the Federal Republic and the GDR) occupied a leading position in the fur processing industry.

Production

How many skins are processed for a single fur piece depends on the size of the fur, the type of garment, the fashion and how elaborately the shape is designed. A straight coat of 100 cm length in clothing size 38 has a surface area of about 25,000 cm². Parts of the coat that are not used directly, such as tails, paws or head pieces, are put together to form "panels", which are later used to make garments. The main place of "body" or panel production is Kastoria in Greece. Below are the average usable areas of the individual fur types with the fur consumption for a straight coat.

| Average pelt area and pelt consumption for a 100 cm long straight coat | ||||

| Subject heading | cm² | Piece skins | Comment | |

| Muskrat | 600 | 46 | The dewlap (belly) and the back are usually | |

| Chinchilla | 420 | 64 | ||

| Feh | 350 | 80 | The dewlap (belly) and the back are usually | |

| European red fox | 2.520 | 10 | ||

| noble-foxes blue fox, | 3.200 | 8 | By interposing | |

| Kanin | 700 | 38 | ||

| Lynx | 3.150 | 9 | The dewlap (belly) and the | |

| Mink, "Females" (female pelts, manes) | 1.000 | 28 | ||

| Mink, "Males" (male pelts, males) | 1.350 | 20 | ||

| Nutria | 900 | 30 | ||

| New Zealand possum | 880 | 32 | ||

| Persian (or Karakul) | 1.400 | 18 | ||

| Sable | 450 | 58 | ||

Redesign

→ Main article: Pelzumgestaltung

Furs can be reshaped several times. Since the fur has been assembled from individual skins, it can be reshaped by repartitioning the skins. The motivation for a change is mainly the change of fashion, change of figure, change of owner or removal of wear marks. During the alteration, the piece can be fashionably recoloured at the same time, thus covering any colour changes that may have occurred, and the hair structure can be changed by dyeing or shearing. Another possibility of alteration is the transformation into a fur lining, a blanket or a fur plaid. However, the possibility of reshaping is limited by the natural ageing of furs.

Fur accessories

Accessories made of fur include fur necklaces, muffs, fur gloves, fur stoles and boas, as well as fur hats, fur boots and fur bags. Undergarments and body warmers, now made primarily of stretchy natural fibers such as angora wool, were also made from cat skins until the 1970s. Fur-trimmed overgarments such as hoods and gollers worn by officials and dignitaries developed into official costumes and coat fashions still worn today. The heavy chauffeur and driver coats of the 1920s became a status symbol among college students.

·

Lady with flea fur, probably sable, ca. 1595

·

Sale of stoles, Berlin 1923

·

A sporran, fur-trimmed bag of the Scottish men's costume

· .png)

Fur boa, 1900

An alternation between functionality and status or symbolic content also comes into play in the so-called "fur colliers" with elaborate heads and paws and tails left on the fur. They can be traced back to the cibellini, among others, which were widespread during the Renaissance. The way of wearing was later interpreted as the form of a flea trap and was then as now repeatedly taken up in clothing fashion without reference to flea infestation.

Stoles and boas are components of evening wear. Their use by prostitutes at times brought entire species of fur, such as the silver fox, into disrepute. Silver fox furs from the wild were considered the king of furs and a status symbol of the upper class around 1900. The price dropped from an unaffordable £500 to 50 to 60 shillings just before the Second World War due to the possibility and expansion of breeding. Cheap stoles and fur boas made of silver fox became part of the "streetwalker's uniform" and were taboo for middle-class, self-respecting women.

_1987,_MiNr_782.jpg)

Fur sewing machine on a stamp

"Table" from fox skins

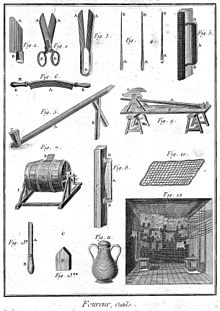

Tools of the trade of the furrier and tailor, from the encyclopaedia by Diderot and d'Alembert 1762-1777

Search within the encyclopedia