Limes (Roman Empire)

Limes (Latin originally "cross path", "aisle", especially "border path" in connection with the division of a space or the development of a terrain, later generally "border"; plural limites) refers to the border ramparts or military border protection systems in Europe, the Near East and North Africa laid out by the Roman Empire from the 1st to the 6th century AD. It is also used for later comparable border demarcations (Limes Saxoniae) or surveillance installations at imperial borders. The term is originally derived from the Latin words limus "across" and limen "threshold". Initially, the Romans understood this term to mean only a field or arable land that was bounded by boundary stones (termini), wooden posts, or by clearly recognizable landmarks (trees, rivers). From the time of Gaius Iulius Caesar onwards, army routes with fortified guard posts and marching posts on a forest line (see also below) or rapidly constructed roads in enemy territory were called limes. In the course of time it developed from a line of march and patrol to an obstacle to approach with control functions.

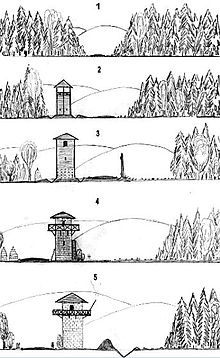

Where there were no natural border markers such as rivers or mountains, the Romans marked their imperial borders with limites. These had different characteristics, they depended on the natural conditions, the settlement density and the threat situation on site. They were all supervised by Roman troops. In North Africa and in the east, more or less loose chains of forts and watchtowers formed the limes. On the Rhine, Danube, Euphrates and Tigris, the watercourses of these rivers marked the border. Today, this limes is also called the "river limes" or "wet limes"; the Romans themselves spoke of a ripa (Latin for "bank"). A section of the Rhaetian Limes in its last stage of development and the Britannic Hadrian's Wall even consisted of continuous stone walls equipped with watchtowers instead of wooden palisades as in Upper Germania and Rhaetia. In late antiquity, however, the Romans generally abandoned these closed ramparts and palisades and switched to securing the limites with forts of various sizes, as had been the practice in some other border sections from the beginning.

In constructing their borders, the Romans did not pursue an empire-wide overall strategy that would be comprehensible over centuries; thus, in the course of the centuries, a multifaceted conglomerate of fixed, but also partly very open borders developed. The Roman border fortifications were not intended to defend against major attacks and were usually not suitable for this purpose. Many of the Roman frontier sections known today could not be defended against large-scale attacks because their garrisons were lined up along a line that even a small, determined fighting force could have easily broken through. The Romans therefore employed what is known as the invasion defense: the presence of large, ever-ready units at strategic points with the ability to fight invaders with an army that could be rapidly massed. Their primary purpose was to control or channel the daily movement of goods and people (preclusion) and to ensure rapid communication of intelligence between guard posts. The Limes was not only a military marker, but above all the border of the Roman economic territory. In addition to their function as a military "early warning system", the limites served as customs frontiers and their border crossings as "market places" for foreign trade with Barbaricum. In their almost five hundred-year history, the border fortifications shaped numerous cultural landscapes and formed the nuclei of many important towns. The best-known Limites are the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes in Germany, at 550 km the longest archaeological monument in Europe, and Hadrian's Wall in Great Britain.

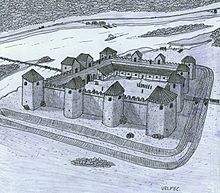

Attempted reconstruction of the 2nd century timber peat fort of Swarthy Hill on the Cumbrian coast.

.JPG)

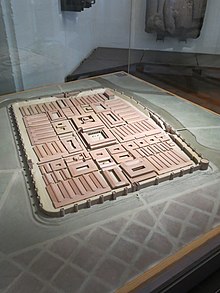

Lower Germanic Limes: Model of the small fort Ockenburgh, 150-180 AD.

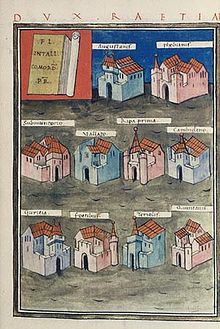

The forts under the command of the Dux Raetiae; representation from a medieval copy of the Notitia Dignitatum

Limes in Germania: Fort Miltenberg (old town)

Rhaetian Limes: Fort Eining, model of the late antique reduction in the north-west corner of the fort

Remains of a late Roman fortified tower in Constance (state of excavation 2004)

Pannonian Limes: The Late Antique Danube Fort of Visegrád-Sibrik

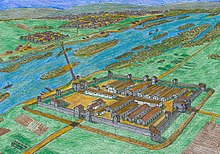

Pannonian Limes: reconstruction attempt of the late antique fort Contra Aquincum, view from south-east

Pannonian Limes: preserved remains of the burgus of Rusovce/Gerulata, Slovakia

Noric Limes: reconstruction attempt of a late antique horseshoe tower (Mautern an der Donau)

DIR-Limes: Findings plan of the excavations in the late antique fort of Arbon (CH)

Noric Limes: Reconstruction model of the late Roman Quadriburgus of Oberranna (A)

Upper Germanic Limes: Reconstruction of the barbarian booty recovered from the Rhine at Neupotz

The Augsburg Altar of Victory, a dedication to the goddess Victoria, erected near the Rhaetian provincial capital of Augusta Vindelicorum on the occasion of a Roman victory over a prey community of the Juthungen.

Triumphal relief of the Sassanid Shapur I at Naqsh-i Rustam: Before the Persian king (on horseback) kneels the emperor Philip Arabs; the emperor Valerian stands beside Shapur, who has seized him by the arm as a sign of his capture.

Limes in Slovakia: reconstruction attempt of the fort Iža-Leányvár, condition in the 4th century AD.

Noric Limes: Attempted reconstruction of the north gate of Fort Favianis according to the findings of 1996 to 1997 (Variant B)

Rhaetian Limes: Fort Pfünz in Bavaria. Attempted reconstruction of the main gate, the porta praetoria, according to Fischer (2008) and information from Johnson/Baatz (1987).

Rhaetian Limes: The Rhaetian Wall at WP 14/77, the remains of which can be seen in the foreground

Rhaetian Limes: South view of the Limes gate at Dalkingen in 2009, to the left and right of the passage a so-called "opus reticulatum" masonry work

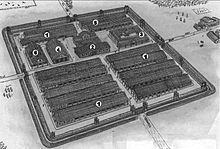

Rhaetian Limes: reconstruction attempt of the early wooden-earth fort of Quintanis (Künzing, D): 1. barracks (contubernia), 2. command building (principia), 3. house of the camp commander (praetorium), 4. storehouse (horreum), 5. horse stables (stabulum), 6. camp hospital (valetudinarium)

Rhaetian Limes: digital reconstruction attempt of the equestrian fort Aalen

Rhaetian Limes: Model of Fort Ruffenhofen

_-_Wp12_77.jpg)

Rhaetian Limes: A wooden watchtower reconstructed in 2008 based on the work of Dietwulf Baatz

Upper Germanic Limes: reconstructed watchtower in the Taunus (D)

Limes in Germania: Palisade and watchtower at Fort Zugmantel

Limes in Germania: reconstructed palisade and ditch near Saalburg Castle

Upper Germanic Limes: Model of the legionary camp Argentorate (4th century AD)

Lower Germanic Limes: Model of the Roman legionary camp in Bonn

Diorama of the rampart fort of Housesteads, condition in the 2nd century AD.

.jpg)

Limes in Britain: Reconstruction of Hadrian's Wall in Wallsend, view from SE

Development phases of the Roman Limes at the northern borders

Coin image of Hadrian, under his rule the Limes took its final shape

German commemorative stamp "UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Limes" (2007)

Roman Limites in the 2nd century AD.

The legion sites around 125 AD.

Battle between Romans and Germanic tribes, marble relief on the Ludivisi sarcophagus, the horseman in commander's pose at the upper edge probably represents Emperor Hostilian (251/252)

Definition

The term limes generally stands for the opening up and division of a terrain or a paved way or free open path that crosses something, a field, a forest, but also the mass of enemies. In a military sense, this is understood to mean a road or path laid out to open up regions of strategic importance to the Romans - such as open countryside, forests, mountainous areas, etc. This also included areas in enemy territory. In this sense, most of the large road constructions (e.g. the Via Appia), which were built for military-political reasons during the time of the Roman Republic, could also be considered limites. In a technical sense, they were understood to mean paths that were created during the surveying of fields (limitatio).

The term limes was not initially applied in Roman antiquity to define a land border. In the republican and early imperial era, such a boundary (fines imperii) was still unknown. Only Augustus' recommendation to his successors to secure the territories they had won so far led to the gradual establishment of fixed borders. The limes was first mentioned by Sextus Iulius Frontinus, who used it to designate aisles cut in the woods in the course of Domitian's Chattian wars as routes of advance. The historian Tacitus used limes to designate a border zone staggered in depth. How the courses of palisades, ditches and ramparts were called by the Romans is unknown. The great ideal of Rome, the unity of the city and the world, is most succinctly embodied in the city wall surrounding and protecting the citizens. It was above all the Emperor Hadrian who tried to realize this ideal with his new frontier policy. It was during his reign that the most familiar form of the Limes began to take shape, with its system of countless fortifications lined up in a row - at first only made of earth and wood, later almost exclusively of stone. In 143, the Greek rhetorician Aelius Aristides gave a speech at the court of Antoninus Pius, which also contained some remarks about the Limes:

["True, you have not neglected the walls, but you have built them around your entire kingdom, not only around your city. You have built them as far outside as was possible, quite splendid and worthy of your name, worthy of being seen by those who dwell within this ring... (Chapter 80) [...] Beyond the outer ring of the circle of the earth you have laid another boundary line, quite similar to the surrounding of a city, which is more mobile and easier to guard. There you set up fortifications and built border towns, each in a different area. Into these you appointed settlers, gave them craftsmen to support them, and otherwise granted them all they needed."

- Aelius Aristides: Ice Rhomen ("Speech on Rome") 80-81

Around the middle of the 2nd century, the Alexandrian historian Appian wrote in his Roman History that the Romans had

"[...] surrounded their empire with great armies, and encircled the whole country and even the sea with a vast and strong fortress."

- Appian: prooimion 7

Under the soldier emperors, that section of a province that shared a common border with the so-called Barbaricum was considered the Limes. From the time of Emperor Constantine I onwards, it was mainly the partial forces newly formed by him, the limitanei (border guards) and the ripenses (riparian guards), that were associated with the limes.

Function

Systematic and scientific Limes research began in Germany in 1892 with the work of the Reichs-Limeskommission (RLK) on the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes. This section of the Roman border fortifications is still one of the best known Limites today. The studies of the Reichs-Limeskommission, which interpreted the Limes from the outset as a defensive bulwark, were groundbreaking, but today, due to new scientific findings, some of their conclusions at the time must be critically questioned.

Even when British archaeologists carried out the first scientific excavations at Hadrian's Wall 100 years ago, the limes was still naturally thought of as a fortification for positional warfare, especially for defence against barbarians. For a long time, therefore, the main subject of debate was the defensive tactics of the Romans: did the soldiers fight the invaders from their forts and ramparts, or did they confront them in advance of the Limes? Later, the experience of the East-West block confrontation with the Iron Curtain separating Central Europe prevented new paths from being taken in determining the true function of the Limes. The image of the Limes as a bulwark against barbarians is therefore still very widespread beyond expert circles. Moreover, the presence of the occupying troops was intended to promote the Romanization of the indigenous population. Through the soldiers, even the most remote corners of the empire came into contact with Rome. Moreover, they were the catalyst that allowed the emergence of a new society on the frontier. Their goal was primarily political - to create roughly stable local governments centered on the cities, with Latin as the official language. At a much lower level, it was aimed at the tribal elites outside and in the frontier areas in order to reconcile them with the Roman occupying power in the long term. This was accomplished through treaties, financial contributions, and the granting of Roman citizenship and the importation of goods and services. In this way, even closer cultural ties were to be forged between Romans and indigenous peoples. The new subjects, however, were not to be completely transformed into Romans, but merely made to identify with the benefits of Roman civilization. Under normal circumstances, the Roman conquerors also did not aim to impose their Italian way of life on a completely foreign culture. Their key to success was not the violent suppression of initial resistance to occupation, but the gradual and voluntary assimilation of the local population into a social system based on wealth and oligarchic power. Opposition to Rome was often overcome or at least mitigated by financial and economic incentives for the subjugated elites and opportunities for promotion in the army or imperial administration. The provinces therefore produced numerous centurions, procurators, senators, governors, praetorians, and emperors. In the frontier zone, the elite's drive was directed specifically toward the accumulation of wealth. Beyond the frontier, Roman diplomacy focused on installing pre-Roman rulers within the tribal hierarchies.

Today, the Limes is regarded by most experts primarily as a population and economic control line, which also served as a demonstration of Roman construction and engineering skills. With the help of the barriers, the Roman administration was able to direct the flow of trade and population in peacetime to the designated border crossings. This enabled the empire to record trade in the provinces, to intervene if necessary and, above all, to levy customs duties. On the other hand, it was also possible to regulate the influx of entire population groups, as needed.

The fact that the Limes was long regarded as an impermeable imperial border is also related to a misinterpretation of a Tacitus text in the 19th century. This was in the context of finds of palisade and wall remains from the 2nd century AD, which could not be dated exactly at the time, and above all the modern view of the border as an absolute dividing line between nation states. Older researchers therefore believed that the Limes was a border of this kind, but this would certainly not have been the intention of the Romans or other ancient peoples. The Limes was anything but an iron curtain, but rather a membrane along which a kind of osmotic exchange of people, goods of all kinds and ideas from over there to over there was part of normal everyday life. Romans traveled to Barbaricum and went about their business there, Teutons and many other tribesmen crossed over to the Empire in return, and by no means always did they come as captives or slaves. Through these numerous contacts, in time the political and military cards were completely reshuffled. Contacts and trade with the Romans had a massive influence on the social structure of the barbarian tribes. In the West, this brought about a completely new constellation of rulers and tribal oligarchies that ultimately even threatened Rome's existence. In the East, the Parthians were succeeded in 224 by the Sassanids, who repeatedly troubled the Romans until the beginning of the Islamic expansion in the 7th century. For this reason, the character of the Limites changed in the 3rd century.

Whether wall or palisade, the architects of the Limes were not concerned with creating a standardized and absolutely gapless barrier. It was primarily intended to convey a simple message to the neighbouring peoples: This is where mighty Rome begins, with all its achievements (e.g. legal security); if someone wants to cross its borders, he must do so at the checkpoints provided for this purpose and thus submit to the laws of the empire in force. Those who do not accept this commit a breach of law and are punished for it. At the same time, it was to be made unmistakably clear to the barbarian tribes that the Romans knew how to defend themselves effectively against encroachments. Until the 4th century the empire then reacted with brutal retaliatory campaigns if necessary. The aspect of illegal trespassing of a visibly enclosed space (e.g. the individual dwelling house as a framed cult and ritual district) was also known to all neighbouring cultures, where it was also regarded as a grave sacrilege and sanctioned accordingly.

Despite the technical and logistical achievements of the Romans in expanding the Limes into a closed barrier, it was also the first sign of their increasing weakness during this phase. The Romans had to admit to themselves that the expansion of the empire had literally reached its limits. The official doctrine of the Augustan age, an ever-growing empire without end, had failed in the face of political and military realities. In time, however, the neighbouring peoples, largely excluded and less advanced in this way, probably drew different conclusions from this than Rome had originally intended. From their point of view, the powerful Rome was apparently so afraid of the barbari from the vast and dark forests of Germania and the eastern steppes, which it despised, that it now entrenched itself behind walls and palisades. At the same time, in the case of a threat from other peoples or scarce resources, the neighbouring Germanic tribes had the incentive to leave their original settlement areas and to cross the Limes in order to be able to participate, in whatever way, in the better life of the Empire (see also Migration Period). The limes stood for a clear demarcation from the non-Roman or barbarian world, but nevertheless gave the peoples of the Roman Empire a feeling of security (securitas) and togetherness for a long time.

Search within the encyclopedia