French Revolution

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see French Revolution (disambiguation).

The French Revolution of 1789 to 1799 is one of the most momentous events in modern European history. The abolition of the feudal-absolutist corporative state as well as the propagation and implementation of fundamental values and ideas of the Enlightenment as goals of the French Revolution - this applies in particular to human rights - were partly responsible for profound power and socio-political changes throughout Europe and have decisively influenced the modern understanding of democracy. As the second among the Atlantic Revolutions, it in turn received orienting impulses from the American struggle for independence. Today's French Republic as a liberal-democratic constitutional state of Western character bases its self-image directly on the achievements of the French Revolution.

The revolutionary transformation and the development of French society into a nation was a process in which historiography distinguishes three phases:

- The first phase (1789-1791) was marked by the struggle for civil liberties and for the creation of a constitutional monarchy.

- The second phase (1792-1794), in the face of both internal and external counter-revolutionary threats, led to the establishment of a republic with radical democratic features and the formation of a revolutionary government that used terror and the guillotine to persecute all "enemies of the revolution".

- In the third phase, the directorial period from 1795 to 1799, a political leadership determined by propertied interests maintained power only with difficulty against popular initiatives for social equality on the one hand and against monarchist restorationist efforts on the other.

In this situation, the decisive factor for order and power increasingly became the citizen army that had been created in the Revolutionary Wars, to which Napoleon Bonaparte owed his rise and the support he needed to realize his political ambitions that extended beyond France.

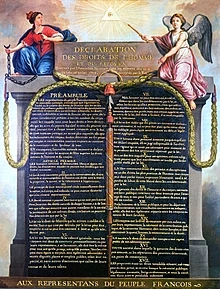

Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen . The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in an account by Jean-Jacques Le Barbier

A major event in the history of European impact

In a recent overview, the French Revolution is described as a founding event that has shaped the history of modernity more deeply than almost any other. It is not only in the minds of the French that this revolution has enormous significance. With the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 26 August 1789, those principles were affirmed on the European continent and positioned against absolutist monarchies, which were laid out in the Declaration of Independence of the North American colonists and which today are propagated and demanded worldwide by the United Nations.

For states with written constitutions and corresponding civil rights guarantees, the three-phase revolution produced several models, each with different emphases on freedom, equality and differentiation of property (e.g. voting rights). Contemporaries of the revolutionary events said soon after 14 July 1789 (storming of the Bastille): "We have crossed the space of three centuries in three days." This was followed by a social and political-cultural upheaval in which printed media created public spheres for political factions as well as, in part, for disadvantaged sections of the population such as the Sansculottes, which also played a role in determining political events in the following 19th century. According to Johannes Willms, the revolutionary process was continuously driven by conflicting interests and forces. "They all sought answers to developments unleashed by the sheer dynamism of the processes." Without exception, he says, they were new challenges "that demanded solutions for which there was no model."

Economically, the abolition of the privileges of the estates, the guilds and the guilds promoted freedom of enterprise and the principle of meritocracy. Culturally, the French Revolution brought about a far-reaching dissolution of the traditional alliance between church and state, with secularism setting limits to religious doctrines. Beyond France and the European continent, the revolutionary events stimulated new revolutionary movements, some of which saw themselves in agreement with the developments in France, but some of which also formed themselves in opposition to them. It was also representatives of disadvantaged social classes who understood the slogans of freedom and democracy according to their own needs and sought to implement them: in the Atlantic region not least slaves, mulattos and Indians.

As an object of experience and research for the interactions of domestic and foreign policy as well as of war and civil war, as an example of the dangers and instability of a democratic order as well as of the inherent dynamics of revolutionary processes, the French Revolution will remain a rich field of study in the future.

Motto of the French Revolution: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity

The pre-revolutionary crisis of French absolutism

Among the multitude of causes discussed in historical research in connection with the French Revolution, a distinction can be made between short-term, acutely effective causes and longer-term, latent causes. The latter include, for example, socio-economic structural changes such as the development of capitalism, which, together with the bourgeoisie that used it, was restricted in its development by the feudal-absolutist ancien régime. The change in political consciousness, which found support above all in the bourgeoisie with the Enlightenment, could thus be used by the latter as an instrument for asserting its own economic interests. For the concrete emergence of the revolutionary initial situation of 1789, however, the factors that were effective in current intensification were decisive: the financial shortage of the crown, the opposition of the aristocracy (and related to this the inability of the country to reform, because the aristocracy blocked necessary reforms), as well as the bread shortage caused by inflation, especially in Paris.

Financial constraints as a permanent problem

When the Controller General of Finance Jacques Necker published the figures of the French state budget (compte rendu) for the first time in 1781, it was meant as a liberating blow to create a general willingness to reform in an otherwise hopeless financial crisis. His predecessors had already made futile attempts to stabilize the state's finances. Necker's figures were shocking: revenues of 503 million livres (pounds) contrasted with expenditures of 620 million, half of which was spent on interest and repayment of the enormous national debt. Another 25 % were spent on the military, 19 % on the civil administration and about 6 % on the royal court. The fact that a sum of 36 million livres (5.81 % of total state expenditure) was spent on court festivities and pension payments to courtiers was regarded as particularly scandalous.

The French crown's participation in the American colonists' war of independence against the British mother country had also contributed significantly to the mountain of debt. Although the intended defeat and power-political weakening of the trade and colonial power rival had occurred, the price for Louis XVI's regime was twofold: not only were the state finances put under additional enormous strain, but the active participation of French military officers in the liberation struggles of the American colonists and the attention paid to their concerns in the opinion-forming French public also weakened the position of the absolutist rule on an ideological level in the long term.

Reform blockade of the privileged

Like all his counterparts before and after him, Necker's plans to improve state revenues met with energetic resistance, which finally forced an already weakened monarchical absolutism to face consequences. The revenue and administrative system of the ancien régime was inconsistent and sometimes ineffective, despite centralist tendencies, as embodied above all by the intendants as royal administrative commissioners in the provinces (see Historical Provinces of France). In addition to those provinces where taxation could be regulated directly by royal officials (pays d'Élection), there were others where the consent of the provincial estates was required for tax laws (pays d'État). Exempt from direct taxation were the first estates, nobility and clergy. The main tax burden was borne by the peasants, who also had to pay dues to landlords and church taxes. Tax lessees were responsible for collecting the taxes. They collected the taxes from the taxpayers in return for a fixed sum to be paid to the crown and could keep any surpluses for themselves - an institutionalised invitation to abuse, as it were. The main revenue came from the salt tax (gabelle), which was particularly hated for this after numerous increases.

Finally, of crucial importance as a brake on reform were the supreme courts (parlements), which could validate, object to, or refuse to approve laws enacted by the monarchical government by registering them. The parlements were the domain of the official nobility (noblesse de robe). Within their rank, the bailiwicked nobles were upstarts, most of whom had acquired noble status by purchasing offices. In safeguarding their privileges and interests, however, they were no less committed than the long-established sword nobility (noblesse d'épée). The increasing refusal of the crown's tax laws practiced in the parliaments found support among the people as well. After all attempts at intimidation by the court had been unsuccessful and Louis XVI's initiative to commit the privileged to his course in a specially convened assembly of notables in 1787 and 1788 had also failed, the government attempted to curtail the privileges of the parliaments. There was then widespread solidarity with the members of parliament. This culminated in riots which took place in Grenoble on the "Day of the Bricks" and in some respects anticipated demands of the later revolution. Ultimately, the king could no longer avoid reconvening the Estates-General, which had been suspended since 1614, if he did not want the crisis in the state's finances to escalate further.

Enlightenment thinking and politicization

It was not only in a central field of practical politics and in the institutional sphere that pre-revolutionary French absolutism showed weaknesses. Enlightenment political thought also questioned its basis of legitimacy and opened up new options for the organization of rule. Two thinkers stand out from the French Enlightenment of the 18th century because of their particular importance for different phases of the French Revolution: Montesquieu's model of a division of powers between legislative, executive, and judicial authority was applied in the course of the first revolutionary phase, which resulted in the creation of a constitutional monarchy.

Rousseau provided important impulses for the radical-democratic second revolutionary phase, among other things by seeing property as the cause of inequality between people and criticizing laws that protected unjust property relations. He propagated the subordination of the individual to the general will (volonté générale), refrained from a separation of powers and provided for the election of judges by the people. Enlightenment thought became increasingly widespread in the 18th century in debating societies and Masonic lodges, as well as through reading circles, salons and coffee houses, which encouraged people to read and discuss the fruits of their reading in a convivial setting. The exchange of opinions on current political issues also took place here in an informal and natural way. The main users were the educated middle classes and professions, such as lawyers, doctors, teachers and professors.

The Encyclopédie published by Denis Diderot and Jean Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert, which first appeared between 1751 and 1772, was a product and compendium of Enlightenment thought with broad appeal. Translated into several languages, it became the Enlightenment encyclopedia par excellence for the European educational world of the eighteenth century: "Packed among many pictorial plates and articles on technology, crafts and trades were the humanities articles that espoused modern ideas and contained explosives to undermine more than one ancien régime."

Inflation as a social driver

The majority of the population in the Ancien Régime was little interested in enlightenment thinking and politicization, but even more so in the price of bread. The peasants, who made up four-fifths of the population, had suffered a bad harvest in 1788 as a result of the Little Ice Age and then endured a harsh winter. The climatic extremes of this decade may also have been exacerbated by the volcanic eruption of 8 June 1783 in Iceland. While the peasants lacked the most basic necessities, they still saw the storehouses of the secular and ecclesiastical landlords, to whom they had to pay dues, well filled. There were protests and demands for sale at a "fair price" when grain prices rose sharply. The little people in the towns were also hit hard by food price increases. By the middle of 1789, bread was more expensive than at any other time in 18th century France, costing three times the price of the better years. Artisans in cities had to spend about half their income on bread supplies alone. Any increase in price had the effect of threatening the existence of the people, and caused the demand for other necessities to fall. "Now discontent and agitation reached those who had not yet been directly reached and mobilized by the public controversy over the financial misery and the inability of the state to function. The economic distress which, as a result of inflation and underproduction, affected urban consumers and then trade and commerce, brought the 'masses' into the political arena."

The encyclopedist Denis Diderot, portrait by Louis-Michel van Loo, 1767

Jacques Necker. Portrait of Joseph Siffred Duplessis, c. 1781

Louis XVI portrait by Joseph Siffred Duplessis, c. 1777.

The encyclopaedist Jean Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert, portrait by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1753

Search within the encyclopedia