Amphibian

The terms amphibians (Amphibia) or amphibians cover all terrestrial vertebrates that, in contrast to amniotes ("navel animals"), can only reproduce in water. In zoology, these terms apply primarily to species living today (recent). Because the term "Amphibia" is less exclusive in vertebrate paleontology and traditionally always includes extinct, early forms of terrestrial vertebrates ("primitive amphibians"), the three recent major groups of amphibians (frogs, caudates, and creeping amphibians) are given the name Lissamphibia for better distinction. Whenever "amphibians" are mentioned in the following, this usually refers to the Lissamphibia.

In amphibians, individual development generally proceeds via an egg laid in water, from which an aquatic (aquatile), gill-breathing larva hatches. This larva undergoes metamorphosis, at the end of which there is usually a lung-breathing adult individual capable of life outside water. The scientific name "Amphibia" (from the ancient Greek adjective ἀμφίβιος amphíbios 'double-bodied'; formed from ἀμφί amphí, German 'on both sides' as well as βίος bíos, German 'life') refers to the two phases of life before and after completion of metamorphosis. However, due to their physiology, all amphibian species are at least bound to habitats with high humidity even in the adult stage. Many amphibians are nocturnal to protect themselves from predators and to keep water losses through the skin low.

Evolution

The recent amphibians with their three major subgroups frogs (Anura, Salientia), caudates (Urodela, Caudata) and creeping amphibians (Gymnophiona, Caecilia) are also called modern amphibians (Lissamphibia) together with their immediate fossil relatives. They, like modern reptiles, birds, and mammals, are evolutionary descendants of a particular group of bony fishes that began expanding their habitat to land areas immediately surrounding inland waters in the Upper Devonian from about 380 million years ago (see Landwalk). Therefore, amphibians are classified in the group of terrestrial vertebrates (Tetrapoda) together with reptiles, birds and mammals.

Within the terrestrial vertebrates, amphibians are considered the most primitive group because, among other things, they depend on water for reproduction, because some parts of their skeleton do not ossify, and because of the relatively low efficiency of their lungs and cardiovascular system. In this they differ from the "higher" terrestrial vertebrates, the sauropsids (including birds) and mammals, collectively known as amniotes.

In their originality, modern amphibians actually resemble to a certain extent the long extinct early land vertebrates, which are also often referred to as "amphibians" (cf. Labyrinthodontia). However, the idea that modern amphibians are direct descendants of the first land vertebrates is outdated. Instead, they are forms that have retained the reproductive mode and lifestyle of the first terrestrial vertebrates and therefore still share similarities with them, but which, especially with the frog amphibians and the creeping amphibians, gave rise to highly derived representatives that differ from the early terrestrial vertebrates in many aspects.

The origin of modern amphibians is one of the most controversial topics in vertebrate paleontology. They do not appear in the fossil record until the early Triassic, more than 100 million years after the first land vertebrates and more than 50 million years after the first amniotes. The origin of modern amphibians could be narrowed down to two major groups of early terrestrial vertebrates, the temnospondyls ("cutting vertebrates") and the lepospondyls ("pod vertebrates"). However, it is still unclear from which of the two groups modern amphibians have evolved and whether their ancestors are actually to be sought in only one of the two groups.

Living reconstruction of one of the oldest known modern amphibians: Triadobatrachus from the Lower Triassic of Madagascar

Morphological characteristics

Physique

Amphibians have a wide range of sizes. They are the smallest known vertebrate, with a body length of barely eight millimeters for an adult individual of the New Guinea frog genus Paedophryne. Giant salamanders, the largest recent amphibians, reach up to one and a half meters in length, but most species do not exceed 20 centimeters. The three major groups of amphibians differ relatively strongly from each other in terms of their habitus. This is not least connected with different modes of locomotion: While caudates move on land by striding or crawling, frogs specialize in jumping locomotion. In addition, both some caudate and some frog species climb trees. A few frog species can even glide short distances. Many creeping amphibians, on the other hand, move by digging in the ground. In water, caudate amphibians swim and dive sinuously using their oar tails, and frogs use their long, powerful hind legs.

Frogs and caudates have a flat and relatively open, creeping amphibians a relatively high, compact and wedge-shaped skull. One of the most important common features of modern amphibians, which also distinguishes them from the early amphibians, the "primitive amphibians", is the special structure of their teeth: a crown, usually covered with enamel, sits on a base of dentin, the so-called pedicle, anchored in the jawbone, with a weakly mineralized zone between the crown and the pedicle. This tooth structure is called pedicellate. Tooth change, as is common in the more primitive terrestrial vertebrates (including modern reptiles), occurs several times during life (polyphyodonty). Compared to the basic structure of land vertebrates, numerous bones have been lost in the skull of modern amphibians, including those that are generally still present in modern reptiles. This concerns elements of the cranial roof (jugals, postorbitals), the palatal roof (ectopterygoid) and the cranium (supraoccipitals, basioccipitals, basisphenoid) as well as the epipterygoid.

In caudates the two pairs of limbs tend to be of equal length, in frogs they are clearly of different lengths. On each hand there are usually four fingers, on the feet five toes. In the creeping amphibians the limbs are completely deformed. Also within the caudate amphibians, a partial or complete reduction of the limbs is found in the arm newts and eel newts. The bony trunk skeleton is partially reduced compared to amniotes. Thus, the ribs are generally short, do not form a proper ribcage, and a sternum is absent. The frog amphibians, whose habitus is generally highly derived, often have no ribs at all. In addition, frog amphibians have only five to nine cervical and dorsal vertebrae, compared to between 10 and 60 in caudate amphibians with their more conservative habitus. The articulation between the cervical spine and the skull is via a paired occipital condyle - the original condition in terrestrial vertebrates is a single median condyle. The pelvis is attached - if not regressed - to the transverse processes of a single pelvic vertebra.

Skin and internal organs

The skin (see also amphibian skin) is thin, naked and hardly keratinized, moist and smooth or also dry-"warty", the subcutis is rich in mucus and venom gland cells as well as pigment cells. It plays an important role in respiration, protection from infections and enemies, and water balance. Amphibians do not drink, but absorb water through the skin and store it in lymph sacs under the skin and in the urinary bladder. It can later be returned to the organism through the urinary bladder wall.

As larvae, amphibians possess gills, as adult animals simple lungs (compare swallowing-breathing), that serve the gas-exchange just like the skin-breathing (including the special-form mouth-cavity-breathing).

Amphibians are cold-blooded; this means that they do not have a constant body temperature, but this depends on the ambient temperature. Their heart consists of two separate antechambers and a single main chamber without a septum, which means that the pulmonary and systemic circulation are only partially separated.

The intestine-entrance, the excretion and internal sex-organs all flow into a single stomach-side body-opening, the cloaca.

Sense organs

For many species, the eyes are important sensory organs and correspondingly well developed. However, motionless objects are only insufficiently perceived, whereas movements form strong stimuli - both in the search for food and enemy recognition as well as in finding sexual partners.

The middle ear of frogs and caudates has two potentially sound-conducting bony elements: the stapes (columella) and the operculum. The operculum is fitted into the foramen ovale of the inner ear and the stapes, a simple bone rod, touches the operculum with its "rear" end (footplate) and may be fused to it. However, the stapes is actually responsible for sound conduction only in frogs, for only these possess an eardrum. As in reptiles and birds, it is in contact with the "front" end of the stapes. However, the tympanic membrane of frogs is probably not homologous to that of amniotes. In caudate amphibians, sound perception occurs primarily through the forelimbs: The operculum is connected to the shoulder girdle via a permanently tense (tonic) muscle (musculus opercularis), which allows ground vibrations (substrate sound) to be conducted to the inner ear. This so-called opercular apparatus is also present in frogs, but there it possibly does not or only subordinately serve the perception of sound. In creeping amphibians the operculum is missing, probably because they do not have a shoulder girdle. In them, the body cavity and the skull probably function as sound conductors.

The sense of smell is quite highly developed, especially in caudates.

Similar to fish, larvae as well as aquatic species of amphibians possess a lateral line system. In larvae of creeping amphibians and salamanders, electroreceptors similar to the Lorenzinian ampullae of sharks have been demonstrated.

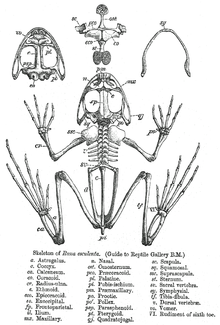

The skeleton of a frog (historical drawing from 1890) with, among other things, the enormously elongated hind legs, the strongly shortened trunk spine, the largely reduced ribs, the strongly elongated pelvis and the reduced tail deviates considerably from the basic structure of terrestrial vertebrates.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the class of animals known as Amphibia?

A: Amphibia are members of the class Amphibia.

Q: What are some examples of amphibians?

A: Examples of amphibians include frogs (including toads), salamanders (including newts) and caecilians.

Q: How do amphibians reproduce?

A: Amphibians lay their eggs in water, usually in a foam nest. After hatching they are tadpoles, which live in the water and have gills. The tadpoles change into adults in a process called metamorphosis.

Q: Where did amphibians originate from?

A: The earliest amphibians evolved in the Devonian from lobe-finned fish which had jointed leg-like fins with digits. They could crawl along the sea bottom. Some had developed primitive lungs to help them breathe air when the stagnant pools of the Devonian swamps were low in oxygen.

Q: How successful are amphibia compared to mammals or reptiles?

A: In number of species, they are more successful than mammals, though they occupy a smaller range of habitats. However, it is said that amphibian populations have been declining all over the world.

Q: What is the smallest frog and vertebrate in the world?

A: The smallest frog and vertebrate in the world is the New Guinea frog (Paedophryne amauensis).

Q: What is the biggest amphibian?

A: The biggest amphibian is the Chinese giant salamander (Andrias davidianus).

Search within the encyclopedia