Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt National Assembly (contemporarily also constituent Reich Assembly, German National Parliament, Reich Parliament, Frankfurt Parliament or already Reichstag as later in the Imperial Constitution) was from May 1848 to May 1849 the constituent body of the German Revolution as well as the provisional parliament of the nascent German Empire. The National Assembly met in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt, hence the name Paulskirche is often used for the National Assembly. As a parliament, the National Assembly also passed the laws of the Reich. On 28 June 1848, the National Assembly established the Provisional Central Power, i.e. a provisional German government, with the Central Power Act.

At the end of March or beginning of April 1848, the Bundestag of the German Confederation had passed a federal election law so that the German people could elect a National Assembly. The election was organized by the individual German states. The National Assembly was to draft a constitution for a German federal state, which was to be agreed with the individual states. However, out of its own sense of power, it also put itself and a central power in the place of the organs of the German Confederation.

The National Assembly adopted the Frankfurt Imperial Constitution (Constitution of the German Empire) on 28 March 1849. In their view, it alone was capable of coming into force. The constitution was accepted by most of the individual German states and both houses of the Prussian Diet, but not by the Prussian king and the large individual states such as Bavaria and Hanover. Austria had de facto excluded itself from the new German Empire by means of a new constitution imposed by the Emperor for a unitary Austrian state.

Prussia and Austria, and then other states as well, ordered the deputies from their countries to resign their mandates in May and now opposed the revolution with open violence. The imperial constitutional campaign failed. Other mandate resignations also shrank the number of deputies until the National Assembly was dominated by the left. At the end of May 1849, the remaining deputies fled to Stuttgart and formed a rump parliament there, which, however, remained meaningless and was already dissolved by the Württemberg military on June 18.

The erstwhile deputies of the constitutional liberals, the right-wing center, met in late June in the Gotha Nachparlament, a private assembly. There they essentially accepted the Prussian attempt to establish the Erfurt Union as a small German state. While many left-wing deputies left Germany or were persecuted, there were a larger number who later served in the imperial assemblies of the North German Confederation and the German Empire. The most prominent was Eduard von Simson, President of the National Assembly, the Union Parliament of Erfurt and the first President of the Reichstag.

.jpg)

Painting Germania, often attributed to Philipp Veit. Under this symbolic image of Germany, the deputies debated in the Paulskirche in Frankfurt.

Ludwig von Elliott: Session of the National Assembly in June 1848

History

Election of the National Assembly

→ Main article: Suffrage in the Vormärz and the March Revolution

At the beginning of the German Revolution, in March 1848, the Bundestag was initially the focus of the all-German renewals. The Bundestag was the highest organ of the German Confederation, with envoys from the individual states. In addition, a pre-parliament was formed, an assembly of representatives of the parliaments of the individual states.

One of the most important decisions of the time was the Federal Election Act, or more precisely two Bundestag resolutions of 30 March and 7 April on the proposal of the lower house of parliament. According to the Federal Election Act, the individual states were to have representatives elected to a constituent German National Assembly. To this end, the Federal Election Law provided them with a basic framework, such as that one deputy was to be elected for every 50,000 inhabitants and that every male, adult, independent citizen was allowed to vote. Due to a lack of provision, the states could decide for themselves whether the election should be direct or indirect.

Although the National Assembly was supposed to convene on May 1, in some states the election took place on that day or later, and it took several days to determine the results. The legal and de facto conditions of the election varied greatly from region to region; the overall turnout is thought to have been between forty and seventy percent.

Final Phase

The rejection of the imperial crown by Frederick William IV of Prussia caused great consternation in the National Assembly. However, it adhered to the Imperial Constitution and elected a committee of thirty to examine the report of the Imperial Deputation. The object was to subdue the princes and governments by public opinion. A note of the Twenty-eight, the plenipotentiaries of smaller states, adopted the constitution, as did the Chamber of Deputies of the Prussian National Assembly. The latter threatened its king that if he continued to reject it, he would no longer support any Prussian government.

The conflict then escalated: at the end of April, the king not only finally rejected the imperial crown, but also dissolved the chamber in Prussia; the same happened in Hanover, Saxony and other states. On May 3 the National Assembly set another deadline for recognition and, by 190 votes to 188 on May 4, determined that it would itself call elections to the first Reichstag instead of the emperor (the Prussian king). This was to elect a new emperor. It called on governments, state parliaments, municipalities and the people in general to bring the constitution to bear. When the left called for violent action, the moderate deputies gradually left.

Like the Austrian government before it, the Prussian government declared on May 14 that the mandates of the Frankfurt deputies from Prussia had expired and that these deputies were no longer allowed to attend the sessions. With the failure of the constitutional agreement, the task of the National Assembly was finished. The Prussian government no longer regarded the National Assembly as the legal representation of the people. Saxony and Hanover followed Prussia's example in May, and Baden in June 1849. The coup d'état-like measure was unlawful, because the elections to the National Assembly were based on state election laws that were still in force, and the state election laws, in turn, were enforcement measures of the federal election law, which was also still in force.

Many deputies submitted and resigned their seats, the last better known of the political centre on 26 May, when the majority called on the people to violence. On May 30, 71 deputies against 64, with four abstentions, decided to move the seat to Stuttgart, fearing the invasion of Prussian troops in Frankfurt. The rump parliament in Stuttgart, numbering about a hundred, was at first tolerated by the Württemberg government, but was dissolved by force of arms on June 18. Most of the deputies fled to Switzerland. The Greater German conservatives remained in Frankfurt (together with the central power), they regarded themselves as the legitimate National Assembly.

Announcement concerning the elections for the German National Assembly, from the Rhineland

The Paulskirche from the outside at the time of the revolution

Functions

The Frankfurt National Assembly initially had only one clear task: according to the Federal Election Law, it was to draft a constitution for the whole of Germany and agree it with the governments. However, when the National Assembly took office, the question arose as to the continued existence of the Bundestag and the establishment of a federal executive. The war against Denmark and other problems indicated a need for action. Thus, the National Assembly also took decisions outside its original task, serving as a parliament in an imperial legislature and cooperating with the central power it established.

Central power

→ Main article: Provisional Central Power

After lengthy deliberations on a federal executive, i.e., a government for the federal or imperial level, the National Assembly passed the Imperial Act on the Introduction of a Provisional Central Power for Germany on June 28, 1848. The provisional constitutional order for Germany provided for an imperial administrator, a kind of substitute monarch, who appointed ministers. For itself, the National Assembly defined the following role in the Central Power Act:

- She elected the Reichsverweser

- The ministers were responsible to her, the overall Reich Ministry

- Ministers had to provide her with information on request

- It decided together with the central power on war and peace and treaties with foreign powers

On 29 June, the National Assembly elected Archduke Johann of Austria as Reichsverweser. He appointed the Leiningen cabinet in July and August and later also other cabinets. Although it was not expressly stipulated that a minister had to resign at the request of the National Assembly, de facto this was the case, partly because the National Assembly represented the most important political backing for the government. A parliamentary mode of government thus prevailed. However, the National Assembly did not have the power to dismiss the Reichsverweser Johann, even if the Stuttgart rump parliament later declared his actions unlawful.

Reichsgesetzgebung

→ Main article: Imperial legislation 1848/1849

The results of the work of MPs include a number of laws and ordinances on various subjects. Some of them deal directly with the activity or status of the deputies, such as the Imperial Act on the Procedure in the Case of Judicial Accusations against Members of the Constituent Imperial Assembly of 30 September 1848. Others relate to the central power, while still others had the purpose, not least, of demonstrating the usefulness of the National Assembly as a lawmaker establishing order and unity by means of rather uncontroversial regulations, above all the General German Bill of Exchange Ordinance of 24 November 1848.

The deputies considered the fundamental rights of the German people to be particularly important; these were actually part of the future constitution, but had already been passed as an imperial law on 20 December 1848. The catalogue of fundamental rights established individual liberties of the Germans, but also, for example, institutional guarantees regarding the administration of justice, and it prohibited punishments such as the pillory and largely the death penalty. Because of the abolition of noble privileges, the catalogue of fundamental rights was naturally not welcomed by absolutely all Germans.

Laws were passed by the National Assembly and then signed by the Reichsverweser and the relevant minister, to be published in the Reichsgesetzblatt. The basis for this procedure was the Imperial Law Concerning the Promulgation of Imperial Laws and the Decrees of the Provisional Central Power of 27 September 1848. No law, but an early resolution of the National Assembly of 14 June 1848 comparable to it, led to the creation of a German Imperial Fleet.

A publication of the Imperial laws in the corresponding law gazettes of the individual states was not necessary for the validity of the Imperial laws. Similar to the central power and the imperial constitution, it was again the small states that recognized imperial legislation in principle, while the middle states and great powers balked. Despite the Federal Reaction Decree of 1851, which combated imperial legislation and its consequences in the state legislatures, the legal legacy of the National Assembly lived on and was partially incorporated into the legislation of the North German Confederation.

Constitutional

→ Main article: Frankfurt Imperial Constitution

Especially after the difficulties in the summer and autumn of 1848 in gaining recognition for the emerging German Empire and its central power, the deputies concentrated on constitutional work. In doing so, they had to take into account the political situation in Germany, especially the dualism of Austria and Prussia, as well as considerable differences of opinion that also existed within the National Assembly. In particular, the territory of the empire and the head of the empire were disputed.

At the beginning, the deputies assumed with the utmost naturalness that the previous federal territory should essentially become the territory of the Reich and that the corresponding part of Austria belonged to it. Austria, however, made it abundantly clear, at the latest at the beginning of March 1849, that it wanted to belong to a German state organization only with all its territories (including Hungary and Northern Italy) and rejected a national parliament. Germany was to be a Greater Austrian confederation. Prussia, on the other hand, sent cautiously positive signals about a German unification. This situation led to the constitution listing the members of the empire along with Austria, but speaking of the possibility of Austria joining the empire at a later date. Similarly, the affiliation of Schleswig to the Reich was reserved for a later settlement.

The majority of the deputies favoured a single person as head of the empire, and that a monarch. The republicans were generally in the minority, but for some time there was still the idea of placing a multi-headed body at the head of the Empire. Votes in March 1849 then led to the decision that the National Assembly would elect one of the German princes as emperor, whose crown would subsequently be hereditary (hereditary imperial solution). The National Assembly also elected the Prussian King Frederick William IV as Emperor at the end of March.

Linked to this was the question of the emperor's power, which was also not decided until March. The right-wing and the centre-right advocated an absolute veto by the emperor, i.e. laws of the Reichstag could only come into force with his approval. The more left-wing deputies wanted only a suspensive veto: the emperor's objection would only have postponed the entry into force of a law. The latter view prevailed through voting arrangements, because some left-wing votes were needed for the solution without Austria (Pact Simon-Gagern).

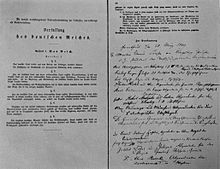

Contrary to the intent of the Federal Election Act of 1848, the deputies proclaimed the constitution on their own authority, without agreement with the state governments. According to the Central Powers Act, the coming into being of the Constitution was also not a task for the central powers. Thus, the Constitution came into force as soon as it was promulgated on 28 March 1849, signed by the President of the National Assembly Eduard Simson and the other deputies. Today's literature is divided on the validity; some authors affirm it, others deny it, others mediately say, for example, that it has not acquired legal force.

Ultimately, it was a political decision at the time whether to recognize it or not. Subsequently, 28 governments, under pressure the King of Württemberg and furthermore the revolutionary regimes in Saxony and the Palatinate recognized the constitution. The fickle King Frederick William IV of Prussia, however, rejected it as well as the imperial crown (finally on 28 April) and, together with other monarchs, put down the revolution.

The Frankfurt Imperial Election Law of 12 April 1849 is in itself a simple Imperial law, although it does materially belong to the Reichstag and thus to an organ of the Imperial Constitution. It was also for practical reasons that the Constitutional Committee removed it from the Constitution. The committee itself had initially proposed an unequal suffrage law that would have again excluded many National Assembly voters from voting. Partly because the Kleindeutsch-erbkaiserliche Partei needed the votes of left-wing deputies, equal and universal male suffrage prevailed for the Reichswahlgesetz. More precisely, the law regulated the elections to the People's House of the Reichstag, but this election did not take place because of the suppression of the revolution.

Signatures of the deputies under the constitutional charter of 28 March 1849

Reichsgesetzblatt with the Reich Constitution

Heinrich von Gagern was at first president of the National Assembly and went in December 1848 to the all-Reichsministerium

The National Assembly was often the target of satire. This cartoonist imagines the many goose feathers that may have been consumed in recording the speeches.

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Frankfurt Parliament?

A: The Frankfurt Parliament was the first freely elected parliament for all of Germany. It was held from May 18, 1848 to May 31, 1849 in the Paulskirche at Frankfurt am Main.

Q: What did the assembly produce?

A: The assembly produced the so-called Paulskirche Constitution which proclaimed a German Empire based on the principles of parliamentary democracy.

Q: What did this constitution provide?

A: This constitution provided a foundation of human rights and proposed a constitutional monarchy headed by a hereditary emperor (Kaiser).

Q: Who was offered the office of emperor?

A: The Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV was offered the office of emperor.

Q: Why did he not accept it?

A: He argued that such an offer was an offence against the rights of the princes of the individual German states.

Q: How were elements of this constitution used in later years?

A: In later years, major elements of this constitution became models for both Weimar Constitution and Basic Law for Federal Republic of Germany.

Search within the encyclopedia