Abductive reasoning

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Abduction (disambiguation).

Abduction (Latin abductio 'leading away, abduction'; English abduction) is an epistemological term introduced into scientific debate largely by the US philosopher and logician Charles Sanders Peirce (1839-1914).

"Abduction is the process by which an explanatory hypothesis is formed" (Peirce: Collected Papers (CP 5.171)). By this Peirce meant a process of inference that differs from deduction and induction in that it extends cognition.

Peirce designed a three-stage cognitive logic of abduction, deduction and induction. In this sense, in the first stage of the scientific cognitive process, a hypothesis is found by means of abduction. In the second stage, predictions are derived from the hypothesis. This involves deduction. In the third stage, facts are sought that "verify" the presuppositions. This is an induction. If the facts cannot be found, the process begins again, and this is repeated until a hypothesis generates predictions for which matching facts can be found.

This impulse has been partly taken up in recent debates in philosophy of science about the nature and methodology of scientific knowledge, but it has also been controversial. Much of the recent discussion has been conducted in the context of the notion of inference to the best explanation. A wide variety of elaborations of a methodology of abductive reasoning have been proposed, as well as applications in various individual sciences discussed, including fields such as cultural studies and semiotics. Various theories about the nature of certain inference procedures in "everyday logic" also use the term abduction.

The abductive conclusion

In the history of logic, the idea of abduction or hypothesis goes back to Aristotle, who mentions it with the term apagoge (First Analytics II, 25, 69a) and also already contrasts it with induction (conclusio). The translation of the term apagoge with abduction was first made in 1597 by Julius Pacius, a Heidelberg law professor.

Peirce, then, did not introduce the term "abduction" into the sciences, but took up a long-forgotten concept and reintroduced it into the language. Peirce's particular achievement is to have examined this mode of inference more closely and to have made it fruitful for the logic of the scientific process. Peirce first used the term "abduction" in about 1893, but he did not use it systematically until 1901. From 1906 onwards, Peirce increasingly used the term retroduction.

In the language of logic, abduction can be described like this:

"The surprising fact C is observed; but if A were true, C would be a self-evident fact; consequently there is reason to suppose that A is true."

- Peirce: Collected Papers (CP 5.189)

It is not a known rule that stands at the beginning, but a surprising event, something that raises serious doubts about the correctness of one's own ideas. Then, in the second step, there is an assumption, an as-if assumption: if there were a rule A, then the surprising event would have lost its surprising character.

Now it is decisive for the determination of the abduction that not the "elimination of the surprise" is the essential thing about it, but the elimination of the surprise by "a new rule A". A surprise could also be eliminated by using known rules. But that would not be an abduction. Rule A has yet to be found or constructed; it was not yet known, at least not at the time the surprising event was perceived. If the rule had already existed as knowledge, then the event would not have been surprising. In the second part of the abductive process, then, a previously unknown rule is developed. The third step then establishes two things: first, that the surprising event is an instance of the constructed rule, and second, that this rule has a certain persuasive power.

Peirce characterized abduction in contrast to the modes of inference of deduction and induction as follows:

"Abduction is that kind of argument which proceeds from a surprising experience, that is, from an experience which runs counter to an active or passive belief. This takes the form of a perceptual judgment or proposition that refers to such a judgment, and a new form of belief becomes necessary to generalize the experience."

"Deduction proves that something must be; induction shows that something is actually operative; abduction merely indicates that something may be."

"Deduction proves that something must be; Induction shows that something actually is operative; Abduction merely suggests that something may be."

- Peirce: Collected Papers (CP 5.171)

Abduction as the starting point of the cognitive process

Peirce saw abduction as the starting point of the cognitive process. What man receives as sense data is perception. "Nihil est in intellectu quod non prius fuerit in sensu. " (CP 5.181, German: "Nothing is in the intellect that was not previously in the senses.") To be distinguished from this are perceptual judgments, in which concepts are formed from what is perceived. In perception, this is "really nothing other than the most extreme case of abductive judgments." (CP 5.185)

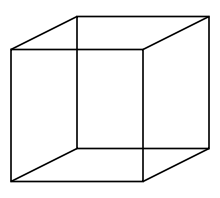

Peirce illustrated the abductive character of perceptual judgments with optical illusions such as the Necker cube. "In such optical illusions, of which two or three dozen are well known, the most startling thing is this, that a certain theory of the interpretation of the figure has quite the appearance of being given in perception. When first shown to us, it appears to be as completely beyond the control of rational criticism as any percept is; but after many repetitions of the now familiar experiment, the illusion fades away, first becoming less apparent, and at last disappearing entirely. This shows that these phenomena are genuine connecting links between abductions and percepts" (CP 5.183).

"This faculty of discernment has at the same time the general nature of an instinct, which resembles the instinct of animals in that it goes far beyond the general faculties of our reason, and guides us as if we were in possession of facts wholly beyond the reach of our senses. It resembles instinct further in that it is in a small degree subject to error; for though it more frequently takes the wrong than the right road, yet on the whole it is the most wonderful of our whole constitution"

- Peirce: Collected Papers (CP 5.173)

.

Necker cube

Search within the encyclopedia