First Indochina War

Indochina War

Part of: Cold War

Foreign legionnaires with a suspected Viet Minh supporter

Indochina War 1946-54

Haiphong - Hanoi - Papillon - Léa - Ceinture - Route Coloniale 4 - Vĩnh Yên - Mạo Khê - Sông Đáy - Hòa Bình - Nghia Lo - Lorraine - Nà Sản - Brittany - Adolphe - Laos I - Atlante - Camargue - Hirondelle - Brochet - Mouette - Laos II - Điện Biên Phủ - Mang-Yang Pass

The Indochina War (1946 to 1954), also known as the First Indochina War or the French Indochina War, was a war in French Indochina between France and the League for the Independence of Vietnam (also called the Việt Minh), which was led by the Vietnamese Communists. The French side sought to re-establish its political rule in the colony. The Viet Minh pursued the goal of an independent communist Vietnamese state. The French colonial power had been temporarily disempowered by Japanese influence and occupation of the colony during World War II, which the Viet Minh used to seize power in the northern part of the country as part of the August Revolution. After a brief period of coexistence between the Viet Minh and the resurgent French, violent clashes erupted in 1946.

Until 1949, the conflict was primarily a guerrilla war of the Viet Minh against the colonial power. From 1949, the conflict developed into a proxy war within the Cold War due to the armament of the Viet Minh by the People's Republic of China, victorious in the Chinese Civil War, and the support of the USA for France. After the defeat of Dien Bien Phu at the 1954 Indochina Conference in Geneva, the colonial power, which was coming under increasing military pressure, agreed to a negotiated settlement, which was largely determined by China and which resulted in the partition of Vietnam through the intervention of the USA. This division of the country eventually led to the Vietnam War. The communist movements of the Pathet Lao and the Khmer Issarak, supported by the Viet Minh, laid the foundation for later communist guerrilla movements in the non-Vietnamese parts of Indochina as well. The war was part of a chain of military conflicts that took place in the countries of Indochina from 1941 to 1979.

Background

French colony in Indochina

During its colonial aspirations in the Pacific region, France encountered the Empire of Vietnam, which could look back on one and a half thousand years of state tradition as a Chinese province and, from the 10th century, as an independent monarchy. The French land grab took place in southern Indochina from 1858, using military force, and by 1887 the colonization of the country had been completed. French colonial policy subsequently divided the country into the two protectorates of Annam and Tonkin, and Cochinchina, which was governed directly as a colony. The emperor remained at the head of the colonial state, but political and military power rested with the colonial authorities and their representatives. The elites of the Vietnamese empire found subjugation by a foreign power traumatic. The population quickly fell into economic hardship as a result of the exploitative policies that followed.

To restore the independent monarchy, the militant Help the King movement rose up shortly afterwards, but the colonial power was able to decide its guerrilla war in its favour by 1897. Under continued French colonial rule, lands became increasingly concentrated among fewer and fewer owners. The new large landowners, European settlers and part of the native elite, in turn leased their land to the growing group of landless peasants. Thus, within a short time, a wealthy class formed in Vietnamese society that benefited from and was loyal to colonial rule. Among the natives who rose to this elite were many Catholics. In Cochinchina, some 70 percent of the land in some rural areas had now passed into the hands of large landowners. The share of the indigenous communal land division system in Cochinchina had shrunk to 3 percent of the land. In the central part of Annam and the northern part of Tonkin, about one-fifth to one-fourth of the land remained in communal hands; however, economic pressure to abandon it was mounting. In the 1930s, about 90 percent of the approximately 18 million Vietnamese were peasants, half of them without land ownership. 0.3 percent of landowners controlled 45 percent of the total cultivated land; 97.5 percent of landowners had only small plots of land under five hectares. Farmers often came under financial pressure from the tenancy system and crop failures and had to borrow. This led to a flourishing of small-scale lenders among the Chinese minority in the country and immigrants who had come from the French colony in India. The inequality of tenure was further exacerbated by high population growth among the rural population.

During the First World War, the French colonial government finally deposed the already politically cold Emperor Duy Tân after he had called for mutiny among colonial soldiers destined for Europe. The interwar period saw an expansion of journalistic and political activity among the local educated elite, which consisted of a few thousand people. The new generation abandoned the traditional Confucian creed of their forefathers and instead propagated a radical cultural and social modernization of the country. The opposition movement found broad support within the population and was able to mobilize some 25,000 people in demonstrations in the mid-1920s. At the same time, the Communist Party of Indochina (CPI) formed out of a small proto-communist movement, often operating in exile. The fifty or so leading representatives of the CPI were educated in Moscow at the Far East University. In the early 1930s, during the Nghe-Tinh uprisings, the KPI managed to mobilize several thousand militant supporters within the rural population. In addition to the communist independence movement, several nationalist organizations also developed. The most prominent of these, the VNQDD, was able to build a broad base of support in Tonkin and in 1930 attempted to launch an armed resistance against the colonial power through the short-lived mutiny of two companies of colonial infantry at Yen Bai. As a result of the events, there were several bombings of French targets in the cities of Indochina. Due to the political and economic tensions in the country, the sects of the Cao Dai (1926) and the Hoa Hao (1939), which were based on Buddhism, were also formed. These groups gained their influence in the power structure of the colony through their supra-regional structure and their own militias.

Loss of power of the colonial state as a consequence of the Second World War

During World War II, France as a colonial power was weakened by the defeat of 1940. The colony fell more and more into Japan's sphere of influence, which further weakened the colonial power's control. In Tonkin's hinterland, the Viet Minh organization constituted itself as a guerrilla organization seeking independence under the control of the Communist Party of Indochina. This established itself in northern Vietnam on the border with China in inaccessible mountainous regions inhabited by minorities with little attachment to the colonial state. Officers Võ Nguyên Giáp and Chu Văn Tấn formulated a plan to seize power in the colony with a guerrilla army built on the periphery. In the context of famine in Vietnam in 1945, the Viet Minh earned the loyalty of millions of peasants by requisitioning and distributing rice. In March 1945, Japanese troops took direct control in the former colony. After Japan's surrender, the Viet Minh succeeded in bringing the cities of Hanoi, Saigon, and Huế under their control in the August Revolution. On the day of the Japanese surrender, September 2, 1945, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the independence of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. The leadership of the Japanese puppet state in Indochina around Emperor BảoĐại offered no resistance. The defining challenge for the DRV was to ensure food security for the population. In the first half of 1946, the majority of the population in Tonkin was limited to one meal a day. The communist government was able to improve the food situation through rationing and command economy, as well as the additional cultivation of maize, yams, and pulses from the middle of the year.

Re-emergence of the colonial power after the Second World War

The political leadership of Free France had always claimed the restoration of sovereignty over all its colonial territories. On the occasion of the Japanese takeover, de Gaulle had reaffirmed the territorial status quo of the colony as well as French supremacy over its defense and foreign policy. In August 1945, British troops under the command of General Douglas Gracey landed in Saigon. The first troops of the French expeditionary corps CEFEO reached Cochinchina in September 1945, and by November the colonial forces were able to re-establish control over the neuralgic points in Cochinchina. Shortly after the Allied takeover of Saigon, acts of violence by Frenchmen formerly interned by the Japanese against the city's Vietnamese civilian population occurred on September 23. Two nights later, several hundred Europeans and half-breeds were taken hostage in the Cité Heraud massacre. Some forty were killed, and the hostages were victims of acts of violence and sexual assault. International investigations blamed the Bình Xuyên criminal syndicate for the attacks on the Europeans. In March 1946, the British formally handed over command to the commander of the Expeditionary Corps, Major General Leclerc. The northern part of the country was occupied by troops of the Republic of China north of the 16th parallel, in accordance with the Potsdam Conference. The latter let the Viet Minh have their way. An agreement in which France relinquished all colonial rights in China to the Republic of China regulated the withdrawal of the Chinese. In March 1946, France reached a compromise with Ho Chi Minh by first accepting Vietnam's independence within the framework of the Union française. This compromise had been brought about by the Chinese refusal to allow French troops to land in Tonkin without an agreement. The compromise between France and the communist leadership in Hanoi allowed the stationing of two divisions of French troops in Tonkin. In October 1946, French troops attempted to restore French customs sovereignty in the port city of Haiphong. When they met resistance, the French responded by bombing the city, causing several thousand casualties among the Vietnamese population. In December 1946, the French side decided to fight the Viet Minh militarily and restore the colony's former status. The actual fighting began on December 12 with the blowing up of the electricity plant and attacks on Hanoi by the troops of the commander-in-chief of the Vietnamese military, General Giap. This was seen by the contemporary French public as the beginning of the war. The Vietnamese side saw the bombardment of Haiphong on 20 November 1946 as the actual start of the war.

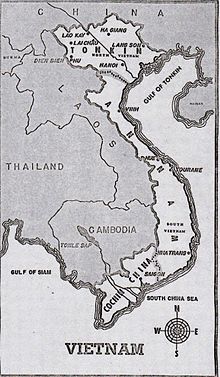

US map of Indochina after World War II; highlights the division of Vietnam into the three constituent states of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina.

Military balance of power

The military apparatus of the Viet Minh was founded in 1944 in the retreat areas within Vietnam. The most important base area was Viet Bac in northern Tonkin near the border with China. Other base areas were located in southern Tonkin and in Annam south of Hue. In Cochinchina, the Viet Minh had only a small base of operations in the south of the Mekong Delta. Based on Mao Zedong's doctrines, the Viet Minh leadership propagated a three-phase course of war with the goal of achieving Vietnamese independence through military victory. In the first phase, Viet Minh forces were to act primarily defensively, expanding their sphere of influence only through guerrilla action. After enough regular troops had been raised and the necessary logistics for them had been created, the war was to move into a phase of "parity" in which the Viet Minh were to further expand the territory under their control in localized conventional operations. In the final phase, superior Viet Minh forces were to wrest military control of the country from the colonial power in supra-regional mobile operations.

Commander-in-Chief Võ Nguyên Giáp summarized the strategy in a post-war publication as follows:

"Only a protracted war could enable us to make perfect use of our political trump cards, to overcome our material disadvantage, and to transform our weakness into strength. [...] We must build up our strength during the course of the war."

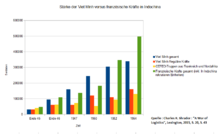

The Viet Minh organization was formed analogously to this doctrine and included three separate troop organizations. The guerrilla forces were primarily part-time soldiers who operated close to where they lived and worked. The groups recruited from one or more villages and carried out guerrilla actions, sabotage operations, and intelligence tasks. The next level was formed by regionally organized, conventionally equipped full-time soldiers who worked closely with the guerrillas within a territory in battalion to regimental strength. At the top were regular forces equipped as light infantry, which were subordinate to the general staff and were to be deployed throughout Indochina. The Viet Minh began in September 1945 with about 31,000 regular soldiers. By the turn of 1948/1949, the regular forces had grown to 75,000. Regional and guerrilla forces provided 175,000 troops. By the end of 1954, the Viet Minh reached 161,000 regular soldiers, 68,000 regional troops, and 110,000 guerrillas.

Viet Minh forces were supported by an elaborate logistics system that ensured food and material supplies mostly through carriers. The strength of civilian logistics personnel varied from around 30,000 to 300,000 during the war.

The source of funding was the siphoning off of the rice harvest and the labor force of the areas politically controlled by the Viet Minh. The supply of the approximately 300,000 Viet Minh soldiers required the transport and distribution of about 110,000 tons of food, mainly rice. To meet the needs in the combat zone of the north, the Viet Minh imported rice on a larger scale from the predominantly pro-French southern part of the country. Through camouflage, close networking with the population and high mobility of their units and camps, the Viet Minh were mostly able to escape the grasp of the colonial forces.

In the summer of 1945, a Communist Chinese regiment retreated to Tonkin due to military pressure from the Nationalists in the Chinese Civil War. They were supported and hidden there by the Viet Minh. In return, the Viet Minh received training assistance from the Chinese exiles. In the process, about 830 soldiers and officers were trained by Chinese cadres until 1947. After the victory of the Chinese communists in the civil war, the Viet Minh received direct supplies of military and civilian material from the People's Republic of China starting in 1949. Estimates put the total at more than one hundred thousand infantry weapons and more than four thousand guns. More than nine-tenths of this material was of US manufacture and had been captured during the Civil War or the Korean War.

In order to ensure the smooth delivery of weapons and supplies, around 100,000 forced laborers built four trunk roads on the Chinese side of the border in the direction of Tonkin. Some 15,000 to 20,000 Viet Minh recruits were trained each quarter in the Chinese provinces of Yunnan and Guangxi with the help of the Chinese military, starting in 1950. Similarly, in August, the People's Republic sent a military mission of several hundred mostly senior officers under the command of General Wei Guoqing to North Vietnam. These assisted the Viet Minh at the division and high command levels as military advisors. The Soviet Union was reluctant to support the Viet Minh. Aid was delivered on a small scale from the GDR and Czechoslovakia.

In December 1945, the French ground forces in Indochina consisted almost exclusively of the 47,000-strong CEFEO expeditionary corps. By December 1946, this had grown to about 89,000 troops and was supported by 14,000 native soldiers. By the end of 1950, 87,000 Expeditionary Corps soldiers and 85,000 indigenous troops were fighting the Viet Minh. By July 1954, French forces included 313,000 indigenous soldiers and 183,000 Expeditionary Corps members.

During the war, no French government ever seriously considered the use of conscripts in Indochina, which had been called for several times by various military leaders. As a result, the Foreign Legion served as an indispensable reserve to lead the Indochina War, providing mostly the most combat-ready units of the Expeditionary Corps. During the war, a total of 78,833 legionnaires served in Indochina. To meet the CEFEO's manpower needs, massive numbers of colonial troops were seconded from North Africa to serve in Indochina. Beginning in 1948, the French military attempted to meet their manpower needs from the colony itself by recruiting locals under the catchphrase of jaunissement (German for "yellowing"). At any given time, about 60% of the combatants deployed were not French nationals. In the same year, the French government allowed those convicted of belonging to units of the Vichy regime or the Waffen-SS to receive amnesty in exchange for deployment in the Far East. From 1948 onwards, some 4,000 French prisoners enlisted.

In order to maintain the personnel strength of the Foreign Legion of just under 20,000 soldiers serving in the CEFEO, the Legion resorted to predominantly German volunteers. Their share of the deployed legionnaires rose from about 35% in the 1940s to about 55% in 1954. In many of the Legion's units stationed in Indochina, German became a lingua franca for the Legionnaires. In 1945 and 1946, up to 5,000 German prisoners of war joined the Legion, making up nearly one-third of the Legion's recruits at the time. According to official orders, members of the Waffen-SS or war criminals were to be barred from service, but this was often disregarded by the recruiting offices. The recruitment of German prisoners was controversial in both Germany and France, and in France led to public expressions of displeasure with the troops. However, the extent of prisoner recruitment was overestimated in both publics. Pierre Thoumelin even raises the question of whether German war criminals were specifically recruited from the ranks of former elite troops (e.g. paratroopers) in order to purposefully use their experience from fighting the partisans in the Balkans.

In the first phase of the war, French forces experienced a relative shortage of materiel and modern vehicles and aircraft. Against the backdrop of the escalating Cold War, the U.S. government, after initial reluctance, shifted to direct material support for French warfare beginning in 1949. This led to the French forces in Indochina as well as the national armies of the French-dependent states of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, formed in 1949, being fully equipped with modern U.S. materiel. From 1950 to 1954, the United States supplied some 30,000 motor vehicles, some 360,000 firearms, 1880 tanks and armored vehicles, and some 5000 artillery pieces. The French forces likewise received 305 aircraft and 106 ships. Among these were two light aircraft carriers. During the course of the war, U.S. materiel supplies met about 70% of the French forces' needs. Among other supplies, more than 500 million rounds were delivered for infantry weapons and at least ten million for guns. The French logistics system was based on fixed depots established during the colonial period, mostly in population centers. The main burden of transport was borne by trucks. In addition, transports were also carried out by river navigation and railways. Transports by porters and pack animals took a secondary role. At all levels, French supply transports were subject to Viet Minh guerrilla attacks and sabotage. This led to a shift toward air transport via airfield or parachute drop. Helicopters were also used to a limited extent. Two separate logistical systems developed in the process. In addition to the static system used to supply troops at population centers, a rapid response system was needed to support combat troops in difficult and remote terrain.

Both sides had to contend with high desertion figures. For the Viet Minh, complete figures are not available from either the French or the Vietnamese side; estimates amount to several tens of thousands. On the French side, there were some 16,000 desertions among CEFEO troops, mainly in colonial units composed of natives. The reasons for the desertions were mostly breaches of discipline or other conflicts with the law. Political motives were in the minority. The formally independent units of the armies of the states associated with France had a higher desertion rate, with some 38,000 men deserting. More than four-fifths of the desertions occurred during the last two years of the war, 1953-1954. A few hundred soldiers defected to the Viet Minh.

Graphical representation of the balance of power between Viet Minh and French and pro-French troops during the Indochina War.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the First Indochina War also known as?

A: The First Indochina War is also known as the French Indochina War, Anti-French War, Franco-Vietnamese War, Franco-Vietminh War, Indochina War, Dirty War in France, and Anti-French Resistance War in contemporary Vietnam.

Q: Who led the French Union's forces?

A: The French Union's forces were led by France and supported by Emperor Bảo Đại's Vietnamese National Army.

Q: Who was on the other side of the conflict?

A: The Việt Minh, led by Hồ Chí Minh and Võ Nguyên Giáp was on the other side of the conflict.

Q: Where did most of the fighting take place?

A: Most of the fighting took place in Tonkin in Northern Vietnam.

Q: Did the conflict spread beyond Vietnam?

A: Yes, it spread over to neighboring French Indochina protectorates of Laos and Cambodia.

Q: When did this war begin?

A: This war began on December 19th 1946.

Q: When did this war end?

A: This war ended on August 1st 1954.

Search within the encyclopedia