First French Empire

First Empire (French Premier Empire) is a term used by historians for the period from 1804 to 1814 and 1815 in the history of France. The official state name was the French Empire (French Empire français). During this period, the French state was a centralist constitutional monarchy in terms of state law, but in practice was ruled largely autocratically by Emperor Napoleon I.

The monarchy was created by the Constitution of the First French Empire, completed by the Senate on 18 May 1804 and confirmed by referendum in November. On December 2, 1804, Napoleon I was crowned emperor in Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral, where he was proclaimed Emperor of the French (L'Empereur des Français). This had been preceded by the coup d'état of Napoleon's 18th Brumaire VIII in 1799.

The period of the Empire was marked by military victories of the Grande Armée in the numerous coalition wars against Austria, Prussia, Russia, Portugal and their allied nations, the beginning of industrialization as well as social reforms. Economically, the country turned into an early industrial nation and, after Great Britain, the leading economic power in Europe at the beginning of the 19th century.

Through an aggressive foreign policy and renewed entry into overseas imperialism around 1800, the French Empire became a world power on a par with Great Britain. In Europe, it dominated large parts of the continent at this time, with the French sphere of influence extending over about a third of the world with the conclusion of several peace treaties and alliances.

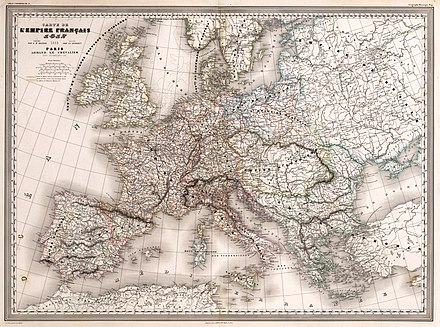

The Empire's territory reached its greatest extent with the annexation of Catalonia in 1812. Located in Western, Central, Southern and Southeastern Europe (Illyrian Provinces), the monarchy had an area of 860,000 km². In addition, there were the colonies, which also belonged to the mother country, with which the national territory of imperial France, without its satellite states, amounted to about 2,500,000 km². On the national territory lived in 1812 about 60 million people, with about 46 million in Europe and 14 million inhabitants in the colonies. This made it the second largest state in Europe in terms of area (after Russia) and the largest in terms of population, and a leading colonial power at the time. Of its 60 million inhabitants, the nobility retained its high social prestige despite the French Revolution and, under Napoleon, was able to reassert its dominant role in the military, diplomacy and higher civil administration. The various reforms - such as that of the judiciary through the Code civil or that of the administration - shaped France's state structures right up to the present day.

The supremacy of the French Empire ended with the catastrophic defeat in the Russian campaign. In the wars of liberation that followed, France fought a multi-front war against the other great powers and suffered great losses as well as the withdrawal of the Grande Armée from the occupied and annexed territories. On April 11, 1814, Napoleon abdicated as emperor and went to Elba. However, after secret arrangements, he unexpectedly returned from Elba on March 1, 1815 and once again took power in France (Reign of the Hundred Days). During this brief period, the constitution was significantly liberalized and a de facto parliamentary monarchy was established. However, with the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, Napoleon was finally overthrown and the Empire dissolved for the second and last time.

Despite military defeat, the first French Empire ushered in the slow liberalization of Europe and the end of courtly absolutism. It had one of the largest armed forces in European history, the Grande Armée.

Napoleon Bonaparte's nephew proclaimed himself Emperor of France in the coup d'état of 2 December 1851 and also attempted to pursue a policy of expansion and hegemony. This so-called Second Empire ended just like the First in a lost war, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71.

In part, revolutionary imperialism became the model for other empires such as those of Brazil, Mexico, China, Central Africa, Haiti (1804-1806), and Haiti (1849-1859).

Previous story

→ Main article: French Revolution and First French Republic

Before the Revolution, absolutism had prevailed since the time of Louis XIV, in which all state power emanated from the king. The citizens and peasants (Third Estate) as well as the nobility (Second Estate) and the clergy (First Estate) had practically no political rights of participation. The state had accumulated large debts. King Louis XVI wanted to reduce this deficit by raising taxes, so in May 1789 he convened the Estates General (French: les États generaux), which were the only body that could decide to raise taxes.

This Estates Assembly consisted of 600 deputies from the Third Estate and 300 each from the nobility and the clergy. However, the Estates General demanded more extensive political participation rights and the creation of a constitution. Therefore, the National Constituent Assembly (Constituante) was constituted in June 1789. After initial hesitation, the king allowed this. However, a little later he dismissed the popular finance minister Jacques Necker. This led to riots in Paris that eventually culminated in the storming of the Bastille. In September 1791, the constitution drafted by the Constituante was adopted by the king, making France a constitutional monarchy. However, the king was labeled a traitor by the people in part because of his attempted escape to Varennes in the summer of 1791, pacting with the enemies of the Revolution, as the other states of Europe viewed the Revolution with skepticism and formed alliances against France. This led France to declare war on Austria in the spring of 1792, resulting in several coalition wars until 1815. In August 1792, the king, suspected of colluding with France's enemies, was overthrown and executed on January 21, 1793. The de facto end of kingship was August 10, 1792, when Louis XVI placed himself and his family under the protection of the National Legislative Assembly and was imprisoned in the Temple. The First Republic, newly proclaimed in September 1792, had to deal with both its external and internal enemies, which grew increasingly out of hand and led to the Jacobin Terror. The Jacobin regime was overthrown in the summer of 1794 and the Directory Constitution was enacted a year later. Despite the military successes achieved by Napoleon Bonaparte, among others, there was an economic decline - also due to corruption in the government. The system came into crisis with the formation of the Second Coalition. Substantial political pressure then emanated from Jacobin-minded deputies in both chambers, leading to the resignation of four of the five directors in May and June. Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès and three Jacobin-leaning directors took their place. For Sieyes, however, this was only a temporary solution; to truly transform the constitution, he needed the support of the military. After various negotiations with other military leaders, he decided in favour of Napoleon Bonaparte after his enthusiastic reception of him following the Egyptian expedition. On November 9 and 10, 1799, the coup d'état of the 18th Brumaire VIII took place, justified by an imminent Jacobin insurrection.

According to the new constitution of 25 December 1799, the first consul was elected for ten years and had far-reaching powers. Alongside Napoléon as first consul, Jean-Jacques Régis de Cambacérès and Charles-François Lebrun had only advisory functions. Thus, the right to initiate legislation rested with the first consul, and he appointed the ministers and other high state officials. The Senate, called the Council of State, also played a strong role. The legislature, on the other hand, was relatively weak. It consisted of the tribunate with 100 members and the corps legislatif (legislative body) with 300 members. While the tribunate had the right to debate laws but not to vote, the legislative body had no power to debate but could only vote. The members of both chambers, moreover, were not elected, but appointed by the Senate. A referendum, the results of which were admittedly glossed over, resulted in the citizens' approval of the new constitution. In the Tribunate there were initially still many critics of Napoleon, but later these were replaced by compliant members. The rights of the Tribunate itself were also increasingly limited. The domestic and foreign policy successes enabled Bonaparte, supported by a referendum, to have himself declared consul for life on August 2, 1802.

The storming of the Bastille (picture by Jean-Pierre Louis Laurent Houel, published 1789)

Development

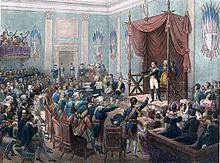

Imperial Coronation of Napoleon I

→ Main article: Imperial coronation of Napoleon I.

After being offered the imperial dignity by a popular vote and the Senate, Napoleon crowned himself emperor on December 2, 1804, in a ceremony attended by Pius VII at Notre Dame de Paris Cathedral. While the acceptance of the imperial crown was intended to further enhance his prestige internally, externally it was an attempt to legitimize his regime dynastically. At the same time, however, the title of emperor signaled a claim to the future shaping of Europe. The title "Emperor of the French" meant that the latter ultimately saw himself as emperor of a people rather than of an empire. Napoleon saw himself as a sovereign of the people and not, like all Roman emperors before him, as an emperor crowned by God (God's Grace). On May 26, 1805, Napoleon was additionally crowned king of the newly created Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy in Milan Cathedral with the Iron Crown of the Lombards.

The Rise of the Empire and the Reorganization of Europe

These coronations led to further conflicts in international relations. Tsar Alexander I entered into an alliance with Britain in April 1805. The goal was to push France back to the borders of 1792. Austria, Sweden and Naples joined in. Only Prussia did not participate in this Third Coalition. Conversely, the German states of Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden, which had been strengthened after the Imperial Deputation, entered the war on Napoleon I's side. In accordance with his previously proven tactic of separating the enemy armies and striking them one after the other, he turned first against Austria. The first blow struck with a lightning campaign against the Austrians at the battles of Elchingen and of Ulm (25 September - 20 October 1805), where General Karl Mack of Leiberich was forced to surrender with part of the army, initially 70,000 strong. This left the road to Vienna open for the Grande Armée: After minor fighting along the Danube, the French troops succeeded in taking Vienna without a fight on 13 November.

Napoleon then lured the Russians and Austrians into the Battle of Austerlitz, which he won on 2 December 1805, by skilfully feigning his own weakness. Although the French fleet was crushed at Trafalgar by Nelson on 21 October 1805, on the Continent Austerlitz meant the decision. On December 26, 1805, the peace treaty of Pressburg was concluded with Austria. The terms were harsh. The Habsburg monarchy lost Tyrol and Vorarlberg to Bavaria, and its last Italian possessions fell to the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy. In gratitude for their support, the Electors of Bavaria and Württemberg were elevated to kings.

In order to ensure success, Napoleon I pursued a targeted marriage policy with the younger members of his family and installed siblings and retainers as rulers of the dependent states. Thus Joseph first became King of Naples in 1806 and then King of Spain in 1808, while Louis became King of Holland in 1806. His sister Elisa became princess of Lucca and Piombino in 1805, and grand duchess of Tuscany in 1809; Pauline was temporarily duchess of Parma and, moreover, duchess of Guastalla. Caroline Bonaparte, as wife of Joachim Murat, became Grand Duchess of Berg in 1806, and Queen of Naples in 1808. Jérôme became king of the newly created Kingdom of Westphalia in 1807. Napoleon's adopted daughter Stéphanie de Beauharnais married Hereditary Prince Charles of Baden in 1806 and became Grand Duchess of Baden in 1811. Only Napoleon's brother Lucien, with whom he had fallen out, went largely empty-handed.

In Germany, the Confederation of the Rhine was founded on 16 July 1806 from an initial 16 countries. Its members committed themselves to military support for France and to leaving the Holy Roman Empire. The protector of the Confederation - as a protector in the political sense of the word or as a protective power - was Napoleon I. Franz II then laid down the imperial crown of the Holy Roman Empire. With it the Old Empire ceased to exist. Already to the year 1808 almost all German states except Austria and Prussia belonged to the Rhine alliance. So to speak a "Third Germany" developed without Austria and Prussia (the triad idea). Extensive centralization of the state system according to the French model - in Germany, which was often still organized as a patchwork of estates - went hand in hand with the introduction of principles of the French Revolution, such as equality, property rights and the like (general fundamental rights), but also with the reform of the agricultural, educational, religious, economic, fiscal and financial systems. In contrast to the comparable Prussian reforms, which were practiced rather harmoniously and from within, beginning in 1806, the French ones were increasingly perceived by the population as rigorous and as imposed from without. The administrative system was often slow and usually only incompletely adopted. It remained a torso, like the entire Napoleonic-Rhenish reform work. The constant drafting of new soldiers, high taxes, disadvantages of the Continental Blockade, repressive measures by the police and military, and strong bureaucratic grip on virtually every citizen led to resentment. Educational reform produced a reliable professional civil service, and the real agent of reform became the senior civil service. Tax and financial reforms brought about an upsurge in trade and a strengthening of the commercial and financial bourgeoisie. Capital markets grew, as did the number of investors, who were now also given guarantees for economic activity through the improved right to property. After Napoleon's abdication, these regions became centers of German early liberalism and early constitutionalism. After the Rhine Confederation project of 1806 to establish a confederation of states with common constitutional bodies failed due to the resistance of the larger member states, the Rhine Confederation remained essentially only a military alliance of German states with France. Napoleon's main goal was to harmonize state structures in order to stabilize French rule over Europe. In case of doubt, power-political and military considerations took precedence over liberal reform ideas. The historian Rainer Wohlfeil notes that Napoleon had no real concept for the reshaping of Europe; rather, the policy of the Rhine alliance, for example, was an expression of a "situational instinctive will to power".

War against Prussia and Russia

In the meantime, France's relations with Prussia had deteriorated. After the latter had concluded a secret alliance with Russia, Napoleon I was ultimatively ordered to withdraw his troops behind the Rhine on 26 August 1806. This the emperor regarded as a declaration of war. He advanced with his troops from the Main through Thuringia towards the Prussian capital Berlin in October 1806. The Prussian army, defeated at the Battle of Jena and Auerstedt, almost disintegrated in the following weeks. The principality of Erfurt was placed directly under Napoleon I as an imperial state domain, while the surrounding Thuringian states joined the Confederation of the Rhine. The Grande Armée marched into Berlin.

Now the Russian army, which had marched into eastern Prussia, supported the Prussian troops that had escaped there. During the campaign, the Napoleonic army's limitations became apparent for the first time. The country was too vast and the roads too bad for rapid troop movements. The supply of the army was insufficient and the Russians under General Levin August von Bennigsen retreated further and further without being engaged in battle. Napoleon I spent the winter of 1806/1807 in Warsaw, where Polish patriots urged him to restore Poland. There he also began his long relationship with Countess Walewska, with whom he fathered a child.

It was not until 8 February 1807 that the Battle of Preußisch Eylau took place without a decision being reached. On 14 June 1807 Napoleon I was able to decisively defeat Bennigsen in the Battle of Friedland. On July 7th France, Russia and Prussia concluded the Peace of Tilsit. For Prussia the dictated peace conditions were catastrophic. All territories west of the Elbe were lost and became the basis for the new Kingdom of Westphalia. The territories incorporated by Prussia in the partitions of Poland in 1793 and 1795 were elevated to the Duchy of Warsaw. All in all, Prussia lost about half of its former territory, had to pay high tributes and was only allowed to maintain an army to a limited extent.

Almost all of continental Europe was now under the direct or indirect control of the French Empire. Against Britain, which remained hostile, Bonaparte imposed a Europe-wide trade boycott with the Continental Blockade.

The years 1807 to 1812

In the years following the Peace of Tilsit, the emperor was at the height of his power. Inside his domain, despotic tendencies intensified during this period. Bonaparte tolerated criticism of his conduct of office less and less. Because Foreign Minister Talleyrand voiced opposition to the expansionist policy, he was dismissed in 1807. The censorship and the control of the press were tightened. The theatrical decree of 1807 restricted the scope of the Parisian stages. The personality cult around the emperor grew. Aristocratization continued. In 1808 a new nobility was created by law. In addition, more and more old aristocrats of the Ancien Régime played a role at court. In large parts of the population, which was still influenced by the ideal of equality of the Revolution, this development was viewed critically.

In foreign policy, the enforcement of the Continental Blockade against Great Britain was in the foreground. In Italy, this was partly achieved by force. With the king's consent, a French army marched to occupy Portugal through Spain. Napoleon I took advantage of the dispute over the throne between the Spanish king Charles IV and his son Ferdinand VII, and in a political coup, backed by French troops in the country, installed his brother Joseph as king of Spain. Immediately thereafter, a general national uprising broke out in Spain, forcing Joseph Bonaparte to flee Madrid. The Spaniards were supported by a British expeditionary force under Arthur Wellesley, later Duke of Wellington. After the surrender of his general Junot, Napoleon himself had to intervene. After trying to persuade the European powers to stand still at the Erfurt Congress of Princes in October 1808, the Grande Armée moved into Spain. Initially quite successful in fighting regular soldiers, the Grande Armée soon found itself embroiled in a bitterly fought guerrilla war with the population. Without having achieved any noticeable success, Napoleon I returned to France at the beginning of 1809. The small-scale war in Spain remained an unsolved problem that tied up large numbers of troops and was costly.

Austria, meanwhile, fomented the burgeoning nationalism and met with great approval in its own monarchy and in Germany. Shortly after his return, the Austrian army under Archduke Charles of Austria-Teschen marched into Bavaria. In Tyrol, under the leadership of the innkeeper Andreas Hofer, the population rose up against the Bavarian occupying troops. In northern Germany, Ferdinand von Schill or the Black Flock attempted to mount military resistance. Especially intellectuals like Joseph Görres, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Ernst Moritz Arndt and others agitated with partly already nationalistic slogans against the French foreign rule. However, Napoleon was still strong enough militarily to keep Prussia and the princes of the Rhine allied to him. Therefore, Austria was largely isolated from him on the continent. Napoleon I arrived in Donauwörth on April 16, 1809. On May 21, 1809, his troops crossed the Danube southeast of Vienna. In the Battle of Aspern-Essling, the Austrians temporarily halted the French advance. It was Napoleon's first defeat and, above all, psychologically an important victory, as the Grande Armée thus forfeited its nimbus of apparent invincibility. In the following battle of Wagram, however, he was quickly able to make up for this defeat and decisively defeat the Austrians under Archduke Charles. In the Peace of Schönbrunn, Austria was forced to relinquish Dalmatia, central Croatia, Carniola, the coastal region, Salzburg and the Innviertel, thus losing about half of its hereditary lands and almost being forced out of the old Roman-German imperial borders. It also had to participate in the anti-British Continental Blockade, reduce its standing army to 150,000 men, and enter into a military alliance with France.

In the same year Napoleon divorced Joséphine, as their marriage remained childless. In 1810, hoping for recognition by the old dynasties and the consolidation of the alliance with Austria, he married Marie-Louise of Habsburg, the eldest daughter of the Austrian Emperor Francis I. The marriage finally produced the desired heir to the throne, Napoleon II, born in 1811. Believing that they had thus established a new dynasty, celebrations were ordered throughout the empire, some of which were to become part of a permanent Napoleonic festive calendar. The weakness of the newly established dynasty was revealed by the conspiracy of General Malet in 1812.

Russian campaign

→ Main article: Russian campaign 1812

At the end of 1810, Tsar Alexander I of Russia was no longer prepared, for economic reasons, to participate in the Continental Blockade against Great Britain imposed by the Emperor of the French. Since Napoleon I saw this as the only means of fighting Britain in the unsuccessful Anglo-French colonial conflict, Russia's position and other factors caused relations between the two sides to cool. Napoleon I prepared for war with Russia in 1811 and the first half of 1812. The Rhine Confederates were obliged to increase their contingents, and Austria and Prussia also felt compelled to provide troops. Only Sweden, under the new crown prince and former French general Bernadotte, kept aloof and allied itself with Russia. In total, the Grande Armée is said to have been 600,000 strong when it marched. However, these figures are now considered exaggerated. In fact, at most 500,000 men were available at the time of the invasion of Russia. Nevertheless, it was the largest army that had existed in Europe up to that time.

On June 24, 1812, the Grande Armée led by Napoleon I crossed the Memel River. His plan for the campaign in Russia, there called the Patriotic War, was to bring about, as in previous lightning campaigns, a quick spectacular decisive battle that would soon end the war and usher in peace negotiations. But the Russian troops, led by Barclay de Tolly, retreated into the far reaches of the country. The previous method of supplying the army from the country's produce did not work as the Russians had a scorched earth policy. In addition, poor logistics and unfavorable weather conditions caused the troop strength to diminish considerably even without contact with the enemy. Already on August 17, 1812, when the troops reached Smolensk, they were only 160,000 strong. In front of Moscow, the Russians under Kutuzov engaged in battle. The Battle of Borodino was won by Napoleon I, but it became the most costly battle of the Napoleonic Wars: about 45,000 dead or wounded on the Russian side and 28,000 on the French side. Not until the First World War were there even higher numbers of casualties in a single day.

Through this Pyrrhic victory, Napoleon I initially managed to take Moscow without further fighting. After the invasion, the city was set on fire - presumably by the Russians themselves. The soldiers of the Grande Armée suffered from hunger, disease, snow and cold. The Tsar refused to negotiate. On October 18, the emperor gave the order to march. Lack of supplies, disease, as well as constant attacks by Russian Cossacks severely affected the French troops. In the Battle of the Berezina, Napoleon's Grande Armee was finally crushed.

Only 18,000 Napoleonic soldiers crossed the Prussian border at the Memel in December 1812. The commander of the Prussian auxiliary corps, Yorck von Wartenburg, separated from the Grande Armée and concluded an armistice with the Tsar on his own authority (Convention of Tauroggen). Napoleon I had already fled to Paris to raise a new army. During the retreat with its heavy losses, the imperial court announced: "His Majesty the Emperor is in the best of health."

Collapse

In Germany, the defeat of Napoleon I led to an upsurge in the national movement. The pressure of public opinion led previous allies of Bonaparte to turn to the opposite side. King Frederick William III concluded an alliance with Russia in the Treaty of Kalisch and called for a war of liberation. At first, only a few German countries followed suit; Austria also initially stayed away from this alliance. Immediately after his return, Napoleon began to raise new soldiers. With a poorly trained army that also lacked cavalry, Bonaparte marched into Germany. In the beginning, Napoleon's military skills showed once again. He was victorious at Großgörschen on 2 May 1813 and at Bautzen on 20/21 May. The reorganized Prussian army had turned into a serious opponent, inflicting heavy losses on the French. For this reason, Napoleon I agreed to the armistice of Pläswitz.

This was used by the opponents to draw Austria to their side. At a peace congress in Prague, Napoleon was given an ultimatum that included the dissolution of the Confederation of the Rhine, the abandonment of the Grand Duchy of Warsaw, and the restoration of Prussia to the borders of 1806. Since this would in fact have meant the abandonment of French supremacy in Europe, Napoleon I did not comply. Thereupon Austria declared war on France. Prussia, Russia and Austria concluded the treaties of alliance of Teplitz. Since Sweden also joined the coalition, all states in Europe not directly or indirectly controlled by Napoleon I now stood against him. In the following campaign, the allies played on their numerical superiority, initially avoiding a decisive battle with the French main army as a result of the Trachenberg strategy and inflicting considerable losses on the troops of the Napoleonic marshals. The range of movement of the main French army was increasingly limited. The final defeat of the French came in 1813 in the Battle of Leipzig. Only a few days before, Bavaria had joined Austria in the Treaty of Ried and declared war on France. In the days of Leipzig the princes of the Confederation of the Rhine, with the exception of the kings of Saxony and Westphalia, changed sides. Napoleon I retreated with the remnants of his army behind the Rhine.

On the Spanish front, Wellington advanced to the French border and France had to give up Catalonia, annexed in 1812. Inside France, public opposition to the regime then arose for the first time in a long time. When the legislature demanded civil liberties, Napoleon I had it closed. Recruitment of new soldiers encountered considerable difficulty because of waning support for the emperor, leaving Napoleon I with only a numerically inferior and poorly trained army to oppose the Allied forces. Nevertheless, in the face of the immediate threat, Napoleon's skill as a commander was once again demonstrated. Despite clearly outnumbered forces, he succeeded in defeating the numerically overwhelming but separately marching enemy several times through skilful and fast-paced manoeuvring. These successes caused him to turn down another peace offer at the Congress of Châtillon. Subsequently, however, it was clear that he was no longer a match for numerical superiority. Therefore, after the Battle of Paris, the allied troops captured the capital on March 31, 1814. The emperor then lost all support from the army, politicians and even close loyalists. On April 2, 1814, the Senate pronounced the Emperor's deposition. On April 6, he abdicated in favor of his son. The allies did not agree. They demanded that the Emperor abdicate unconditionally and offered the treaty of April 11, 1814 for signature. Napoleon signed this offer under the date of April 12, after he is said to have attempted suicide on the night of April 12-13. He was assigned the island of Elba as his residence and only the title of emperor was left to him.

Reign of the Hundred Days and Waterloo

→ Main article: Reign of the Hundred Days

After his abdication, Napoleon went to the island of Elba in April 1814. He was now the ruler of a principality with 10,000 inhabitants and an army of 1,000 men. He began extensive reform activities, but as the former ruler of Europe, they did not fill him. Through a network of agents he knew full well that there was widespread discontent in France after the Restoration under Louis XVIII. Encouraged by these reports, Napoleon returned to France on March 1, 1815. The soldiers who should have stopped him defected to him. On March 19, 1815, King Louis fled from the Tuileries. Although the constitution of the Empire was partially liberalized, approval of the restored Napoleonic regime remained limited.

Alarmed by the events in France, Austria, Russia, Great Britain and Prussia then decided to intervene militarily at the Congress of Vienna. On March 25, they renewed their alliance of 1814.

Despite all the difficulties, Napoleon I managed to raise a well-equipped army of 125,000 experienced soldiers. He left a provisional government under Marshal Davout in Paris and marched against the alliance. As usual, Napoleon I planned to defeat the enemies one by one.

Initially, at Charleroi, he succeeded in driving a wedge between the British army under Wellington and the Prussian troops under Blücher. On June 16, he defeated the allies at the Battle of Quatre-Bras and the Battle of Ligny.

On June 18, 1815, Napoleon I attacked Wellington's Allied army near the Belgian town of Waterloo. Wellington managed to essentially hold the favorable position against all French attacks. The Prussian troops under Marshal Blücher arrived in time and Napoleon I was defeated.

The end of this battle effectively meant the end of the rule of the Hundred Days. On his return to Paris, Napoleon I resigned on 22 June 1815, having lost all support among Parliament and former loyalists. Neither the hope of emigration to America nor political asylum in Great Britain was fulfilled, instead he was exiled to St. Helena in the South Atlantic by order of the Allies and the Empire was dissolved.

After the Congress of Vienna, France was able to keep its pre-apoleonic territory (including Alsace and Lorraine). The Restoration took place and the Kingdom of France was revived. It was not until 1852 that there was once again an Emperor of the French, Napoleon III (Second Empire).

Battle of Waterloo

Napoleon's Farewell to the Imperial Guard at Fontainebleau (painting by Antoine Alphonse Montfort)

Napoleon in retreat (painting by Adolf Northern)

The Coronation of Napoleon at Notre Dame (1804) (Painting by Jacques-Louis David 1805-1807)

Homage of the Princes of the Rhine Confederation (coloured lithograph by Charles Motte 1785-1836)

Napoleon's entry into Berlin on 27 October 1806 (history painting by Charles Meynier, 1810)

3 May 1808 - Execution of Spanish insurgents (painting by Francisco de Goya from 1814)

Map of the French Empire (1812) and its 133 departments, with the Kingdom of Spain, Portugal, Italy and Naples and the Confederation of the Rhine, Illyria and Dalmatia.

Search within the encyclopedia