Fief

![]()

Lehen and Lehenbrief are redirections to this article. For other meanings, see Lehen (disambiguation) and Lehenbrief (mining).

![]()

This article or subsequent section is not sufficiently supported by evidence (e.g., anecdotal evidence). Information without sufficient evidence may be removed in the near future. Please help Wikipedia by researching the information and adding good supporting evidence.

The feudal system (also feudal or beneficiary system from the Latin feudum, feodum or beneficium) was a system of rule and ownership developed in medieval Europe. It was based on the comprehensive hereditary right of use that a feudal lord granted his vassals or liegemen over a thing belonging to him, the fief or feudal estate, as well as on a reciprocal vow of loyalty.

At the top of the so-called fief pyramid is the emperor or king, who grants parts of the imperial estate as crown fiefs to his vassals, with which they in turn enfeoff their sub-vassals or after-vassals. The fief may thus consist of a territory, a plot of land, or a complex of plots of land over which the feudal lord exercises land or landlordship. The base of the fief pyramid is formed by the unfree peasants. The legal principles governing the feudal system form the feudal law.

The feudal system was characteristic of feudalism and the political-economic system of the European Middle Ages. But also in other cultures, especially in Japan (see Han for the princely fiefs and Samurai for the feudatories), structures developed that can be compared to the European feudal system.

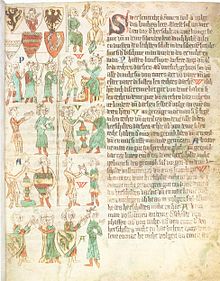

The Heerschildordnung of Eike von Repgow offers a classification of medieval society, Heidelberg, University Library, Cod. Pal. Germ. 164, fol. 1r

Essential principles of feudal law in the Holy Roman Empire.

The essential requirements (essentialia feudi) included:

- a leaning object,

- the active feudal capacity of the lord and the passive feudal capacity of the vassal, and

- the granting of the most extensive rights of use (usufructuary property) as well as the establishment of the mutual relationship of fealty (fidelitas feudalis).

Stretchable objects

Originally, only real estate was considered feudal, especially buildings. Generally, the feudal lord was provided with land or free houses in return for his services. It also happened that he performed services at the lord's court and was fed there. Usually, however, these so-called servi non cassati received a fief as soon as one became free.

Later, the concept of objective feudal capacity was expanded to include all objects and rights that granted the possibility of continued use, in particular state sovereign rights (Regallehn) and incorporeal objects such as offices. These included not only the arch offices of the empire (associated with the electorship), the hereditary offices at the royal court as well as the numerous court offices at the princely, count's and bishop's courts, but also special duties - in this way, for example, the postal services offered by the houses of Thurn und Taxis and Paar were converted into postal fiefs, for the Imperial Imperial Post Office even associated with a seat in the Perpetual Diet.

There were also fiefs of ecclesiastical rights, ecclesiastical fiefs (Stiftslehen, feuda ecclesiastica) and mortgages with the endowments associated with an altar (feudum altaragli).

Regular cash payments from the crown treasury or profits from certain customs duties could also be granted as fiefs, for example as a reward or consideration for military service, political support or other services, but also, for example, the tithe feud, which had a tithing right as its object, the hunting feud, the coat of arms feud or the court feud.

Also the territories of the empire which were not subject to the sovereignty of the king (feuda regalia) were granted by the king, in a solemn ceremony, to the electors, princes and counts by handing over their coat of arms flags as symbols for the obligation to follow the army, therefore as so-called flag fiefs, or as so-called sceptre fiefs to the archbishops and prince-bishops.

Feudal Capability

The capacity of the feudal lord (active feudal capacity) presupposed the authority to dispose of the object and the capacity to acquire those rights and enter into those obligations which were established by the feudal relationship. In principle, only the sovereigns were capable of active feudal tenure. Passive feudal capacity presupposed the earning capacity required for the object of the feud and the ability to meet the personal obligations arising from fealty. Absolutely incapable of feudal tenure were therefore those who lacked this earning capacity, as well as the dishonorable. Only relatively incapable of feudal service were those persons who merely lacked the ability to perform the feudal services which the feudal lord could dispense with, such as the infirm, women or the immature, and in the case of knightly or helmeted fiefs also all persons who were not of knightly birth.

Feudal relationship

The king gives land or offices to crown vassals, who pass them on to sub-vassals, who then pass them on to peasants who are not free. There was no feudal relationship between peasants and sub-vassals in the so-called feudal pyramid.

The social ranking of the feudal pyramid corresponded to the order of the army shields that developed in Germany in the course of the Middle Ages, which was structured as follows in the 13th century according to the law book of the Sachsenspiegel:

- King

- Ecclesiastical princes

- Secular princes

- counts and barons

- Ministeriale (here: upper class of the unfree servants)

- Men of the ministers

- Knights (middle and lower class of the unfree servants, they could only accept fiefs, none could be given)

In the beginning, only free men who were able to bear arms and in full possession of their honor were eligible for fief. After rights of authority, namely the county and the dukedom, could also be given in fief, a hereditary intermediate power developed between the crown and the mass of the population. Until the 13th century, the so-called feudal nobility formed the social upper class, which was divided into various social and economic classes (princes, counts, so-called noblemen). Later on, also unfree, smaller ministerials could bear fiefs (so-called Inwärtseigen), which then formed the so-called knighthood in large numbers. These newer fiefs are not to be confused with the older service property of the ministerials, which was provided according to a different right.

The feudal service consisted mainly of military service and court service (the presence of the vassals at court to provide advice and assistance). The court journey later developed into the land and imperial days. The feudal estate was given to the vassal only for use, later the vassal also became a sub-owner, but the feudal lord always still held the rights to it. Finally, the inheritability of the feudal estate developed later, but the feudal lord still remained the owner.

Justification

The establishment of a feud usually took place through an investiture (constitutio feudi, infeudatio). In Frankish times, this was done by the so-called "Handgang", in the centre: the feudal lord placed his folded hands in the hands of the feudal lord, which the latter clasped. In this way he symbolically placed himself under the protection of his new lord. Since the end of the 9th century, this act has been supplemented by an oath of fealty, which was usually taken on a relic. The oath was not only intended to establish the bond between the partners, but to emphasize that the feudal lord did not lose his status as a freeman, for only freemen could bind themselves by oath. The fiefs issued were recorded in the fief book.

In the 11th century, the investiture included the homage (also Lehnnahme or homagium, today homage) from the course of action and a declaration of will of the feudal lord. A declaration of will by the lord could also be made, but was often omitted. This was followed by the oath of fealty and sometimes a kiss. Because in the Middle Ages a visible sign belonged to a legal act, an object was symbolically handed over, this could be a staff or a flag (so-called "Fahnenlehn", with secular princes), the ecclesiastical princes of the realm were enfeoffed by the king by handing over a sceptre ("Zepterlehen"). With increasing writing, a document was also issued on the enfeoffment, which over time listed in increasing detail the goods that the feudal lord received.

The record of the investiture to be drawn up by the feudal court (Lehnsgericht, Lehnshof, Lehnskurie), later by the Lehnkanzlei, is called the Lehnsprotokoll. The vassal may demand the issue of a letter of fealty, i.e. a document in which the investiture is attested together with its conditions. The document by which the vassal is provisionally certified that the investiture has taken place is called a feoffment deed or recognition deed; the document by which the vassal certifies to the liege lord that the investiture has taken place and that he is bound by the feoffment obligation is called a feoffment reversion (counter-deed). A feudal inventory, i.e. a description of the feudal property with its pertinences, signed by the lord of the feud or by the vassal (Lehnsdinumerament), may be demanded by either of them from the other. A feudal contract (contractus feudalis) is a contract by which a loan is agreed and prepared.

In the late Middle Ages a fee was demanded for the enfeoffment, which was often set at the annual yield of the feudal estate.

The feudal property (beneficium) that the feudal lord received could be the property of the feudal lord or of another lord. Sometimes the feudal lord also sold or gave his property to the lord and then received it back as a fief (oblatio feudi). This so-called feudal commission consisted of someone, in order to place himself under the protection of a more powerful feudal lord, transferring his allod to him as property in order to receive it back as a fief. This was usually done in the hope that the feudal lord would be better able to defend the land in a dispute in the field or in court. The latter bought or accepted the gift because he intended or hoped to combine previously unconnected feudal estates and thereby increase his sphere of influence, e.g. on jurisdiction or the filling of parishes.

Design

From the 11th century onwards, the vassal's duties were usually described as auxilium et consilium (help and advice). Here, help usually refers to the war service that the vassal had to perform. This could be unlimited, i.e. the vassal had to support the lord in every war, or it was limited in time, space and according to the amount of soldiers raised. With the advent of mercenary armies, the conscription of vassals became less important and their service was increasingly transformed into service at court and in administration. Consilium meant above all the duty to appear at court days. Vassals whose liege lord was not the king attended the feudal lord's councils. They also had to dispense justice on behalf of the feudal lord over his subjects.

The vassal could also be obliged to make monetary payments; in England in particular, war services were transformed into monetary payments ("adäriert") and the English king used the money to finance mercenaries. Monetary payments were also required in other cases, such as to pay a ransom for the lord captured in war, at the knighting of the eldest son, for the dowry of the eldest daughter, and for the journey to the Holy Land.

Furthermore, the liege lord could demand from the vassal the renewal of the investiture (renovatio investiturae) in the case of changes in the person of the liege lord (changes in the ruling hand, lord's case, principal case, throne case) as well as in the case of changes in the person of the vassal (change in the serving hand, liege case, vassal case (man case), secondary case). A vassal as successor had to submit a written request (Lehnsmutung) within a year and day (1 year 6 weeks 3 days) and ask for renewal of the investiture; however, this period could be extended upon request by order of the liege lord (Lehnsindult).

Under particular law, the vassal was, apart from the fees for revival (Schreibschilling, Lehnstaxe), sometimes also obliged to pay a special fee (Laudemium, wine purchase, feudal money, feudal goods, manual wages). Finally, in the event of a felony on the part of the vassal, the feudal lord could confiscate the fief by means of the so-called action of privation, prevent deterioration of the estate by judicial measures if necessary, and assert the right of ownership against third unauthorized owners at any time.

The duties of the lord, on the other hand, were less precisely circumscribed; they were largely discharged with the transfer of the fief. The vassal also had a claim to loyalty to the lord of the feudal estate (feudal protection), and a breach of this entailed for the lord of the feudal estate the loss of his superior property. The vassal had the usable property in the feudal object. The lord also had to represent his vassal in court.

Resolution

Originally, a feudal bond was a lifelong loyalty relationship that only death could end. It was also inconceivable that one would render feudal service to more than one lord. In fact, however, multiple vassalage arose in the late 11th/early 12th century, which considerably relaxed the feudal lord's duty of loyalty. In addition, feudal property could gradually be acquired as personal property (allodialisation). The possibility of bequeathing a fief, which went hand in hand with this, also reduced the feudal lord's scope for intervention and loosened the feudal lord's personal duty of loyalty. If the feudal lord violated his duties of protection and care, the feudal lord could, under certain circumstances, terminate his loyalty (diffidatio). Over time, the importance of the feudal estate increased more and more, while the duty of loyalty receded more and more into the background, and in the end a fief was simply an estate for which the heir had to perform a certain ceremony.

The term "reversion of the fief" (Lehnseröffnung, Apertur, Apertura feudi) was used to describe the expiration of the vassalage rights to the fief established by the feudal investiture, so that the so-called usable property (dominium utile) of the vassal was united with the superior property (dominium directum) of the feudal lord in the hands of the latter.

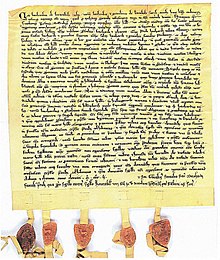

Feudal charter of the noble family of Berwinkel from the year 1302

Army shield order in the Oldenburg illuminated manuscript of the Sachsenspiegel

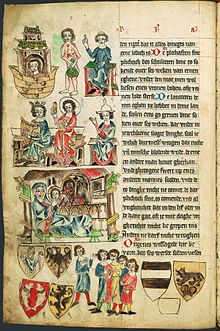

Document on the enfeoffment of Götz von Berlichingen with Hornberg Castle

Present-day families, house and place names

An echo of the former feudal system can be found in family names such as Lehner, Lechner or Lehmann as well as in a large number of house and place names which still have the term "Lehen" in their name, for example Lehen (Freiburg im Breisgau), Lehen (Stuttgart) or Lehen (municipality of Oberndorf).

Search within the encyclopedia