Femicide

![]()

Frauenmord is a redirect to this article. For the TV crime thriller, see Tatort: Frauenmord.

Femicide is the killing of women and girls because of their gender. The term, coined by feminists, first gained currency in the United States beginning in the 1990s. Several academic disciplines, including sociology, epidemiology, and public health, developed approaches to analyze murders of women in terms of contexts, perpetrator profiles, and risk and protective factors. The individual disciplines each developed their own definitions of what constitutes a femicide. A more precise distinction is made between a femicide caused by killing by an intimate partner (so-called intimate femicide), a murder in the name of "honour", a dowry-related femicide and a non-intimate femicide. Globally, while five times as many men were murdered as women in 2017, women accounted for nearly two-thirds of the victims in intimate partner or family homicides. In 2017, 1.3 out of every 100,000 women in the population worldwide fell victim to intimate or familial femicide.

From the 2000s onwards, Latin American activists and feminists used the concept in a modified form ("feminicidio") to denounce violence against women in Latin America. They framed feminicidio as a state failure. Starting in 2009, the United Nations took up the concept because, as UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women Rashida Manjoo stated, violence against women had reached alarming levels. In 2015, Manjoo's successor Dubravka Šimonovic established the Femicide Watch. She called on all countries to regularly submit statistical reports on femicide and its prosecution on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women on 25 November.

Crosses in Lomas del Poleo Planta Alta (Ciudad Juárez, Mexico) at the site where eight bodies of women victims of femicide were found in 1996.

History and definitions

Based on the Latin femina 'woman' and caedere '(here:) to kill', the English-language term femicide was first coined in England at the beginning of the nineteenth century. A legal dictionary of 1848 defined the term as 'the killing of a woman'. The neologism remained largely unused until the 1970s. Then feminists coined the term anew, independently of its old usage, and gave it a political, feminist meaning. In 1976, sociologist Diana E. H. Russell used the term publicly for the first time at the International Tribunal on Violence Against Women in Brussels. At that time, as she later wrote, she used it implicitly in the sense of "hate killing of females perpetrated by males".

Beginning in the early 1990s, the term gained currency. In 1990, Jane Caputi and Diana Russell published the article "Femicide: Speaking the Unspeakable" in the feminist journal Ms. , in which they analyzed the 1989 rampage at Montréal Polytechnic, in which the perpetrator had specifically killed female students, as femicide. In 1992, Jill Radford and Diana Russell edited a collection of essays ranging from domestic femicide in the United States to racialized lethal violence against African-American women and serial murders of women to witch hunts in the past. In the introduction, Jill Radford briefly characterized the term femicide as "the misogynistic killing of women by men" (in the original, "the misogynist killing of women by men") and explicitly related it to sexual violence. That same year, Karen Stout published the first scholarly article treating the killing of women by their partners as femicide. She recommended an "ecological framework" (in the original "ecological framework") for the analysis, which integrated the different process levels (micro, meso and macro level), which was taken up in the scientific research on femicide.

Approaches to the analysis of femicide

The publications in 1992 had a groundbreaking effect. After that year, the term femicide became established both as a political concept and for scientific research on it. In the following years, researchers used five fundamentally different approaches to analyze femicide: the feminist approach, the sociological approach, the criminological approach, the human rights approach, and the decolonial approach. Each approach led to its own definition of femicide.

Feminist approach

In this approach, feminists examined society as a patriarchy in which men dominate, leading to discrimination against women and even killing them. In patriarchy, discrimination against women was culturally sanctioned and embedded in all social institutions. Cases of violence against women, rape and femicide were cited as facts, as well as the unequal distribution of employment rates, wage and status disparities between the sexes, and much more. Among the important proponents of this approach are Diana Russell and Roberta Harmes, who in 2001 produced another important collection of essays on the femicide issue, Femicide in global perspective, in which they refined the definition of femicide to "the killing of females by males because they are female". Russell and Harmes chose this definition to cover all manifestations of male sexism. Russell refers to the killings of females by females because they are females as "female-on-female murders" and deliberately distinguishes them from the term femicide.

Scholars criticized the feminist approach on the one hand for ignoring differences and changes in gender relations. On the other hand, the approach makes every woman a potential victim without distinction and prevents a differentiated analysis from which countermeasures could be derived. The generality of the hypothesis makes it difficult to quantify the extent.

Sociological approach

The sociological approach focuses on examining the circumstances surrounding the killing of women. For this line of research, a 1998 special issue of the journal Homicide Studies was a turning point, in which Jacquelyn Campbell and Carol Runyan redefined femicide as "all killings of women, regardless of motive or perpetrator status". The focus of this empirical research is to identify contexts, case types, perpetrator profiles, and murder cases in which gender plays an important role but is not the only explanation. Different cases and contexts will be identified in order to find out how to effectively prevent women's violent deaths. The approach emphasizes that the social circumstances of women and men differ and that women and men are murdered by different types of perpetrators. The very fact that women are predominantly killed by their intimate partners or in a family setting, which is predominantly not the case for men, makes femicide a social phenomenon in this view.

Criminological approach

The criminological approach treats femicide as a subset of homicide. This approach has been followed since the early 2000s, especially in the disciplines of epidemiology and public health nursing. Secondary to the approach is a clear and separable definition and application of the term femicide. Authors in this discipline often use the terms femicide and killing of women interchangeably in scholarly publications. Some restrict this to "killing of an adult woman," while others consider only the killing of a woman by her current or former intimate partner. Still others use their own, more specific terms such as "lethal intimate partner violence." In some cases, the term is avoided but used equivalently in terms of content, as for example by the 2012 Handbook of European Homicide Research, which analyses "homicide against women" (in the original "female homicide"). The studies of this approach examine in detail killings of women in terms of age, ethnicity, citizenship of the victims and degree of social equality. Regardless of differences in terminology, there is consensus among researchers in this vein that no less than 50% of intimate partner femicides are characterized by a history of domestic violence. The strongest predictors of fatal risk exist at the individual level. Progress in gender equality tended to reduce risk, but there could be backlash as women begin to achieve the same status as men.

The progressive softening and generalization of the femicide definition in the sociological and criminological approach was criticized, as the concept is robbed of its political meaning in this way.

Human Rights Approach

The human rights approach developed from 1993, after the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Resolution Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women. The realization that femicides were increasing worldwide and going unpunished prompted the Academic Council of the United Nations System (ACUNS) in Vienna to hold regular symposia on femicide. The goal of the symposia was to encourage member states to take institutional initiatives to improve femicide prevention and legal protections for survivors of violence. ACUNS describes femicide as a wide-ranging phenomenon that includes murder, torture, honor killing, dowry-related killings, infanticide, gender-based prenatal selection, genital mutilation, and human trafficking.

Decolonial approach

The decolonial approach analyses cases of femicide in the context of colonial rule, including so-called "honour crimes". Palestinian criminologist Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem developed it in relation to the Middle East and North African countries. Shalhoub-Kevorkian pointed out that the criminal justice system, as well as the socio-cultural context in the countries of these regions, would contribute to not prosecuting the perpetrators of violent crimes against women, but instead making excuses for the acts. The female victims would often be held responsible for the criminal acts committed against them. This criminal justice practice views crimes committed against women as private rather than public matters to be dealt with within the family. Shalhoub-Kevorkian's research in the Palestinian Authority area showed that in some cases evidence was deliberately misinterpreted and perpetrators were punished less than they should have been. She attributed the discriminatory legal practice to social and political pressures exerted on the judicial system. This should deal with "more important" issues than honour crimes. She wrote: "Serving a nation under a political banner becomes a license to kill women to protect the honor of those who pretend to have been part of the struggle." (in the original, "Serving a nation under a political banner becomes a license to kill females, in order to preserve the honor of those who claim to have been part of the struggle."). She referred to Leila Ahmed's concept of "the discourse of the colonial domination of the West" and pointed out that "honor killings," for example, have become a symbol of resistance against the colonizers.

In analyzing the sharp increase in violence against women in Ramla during the Israeli occupation, Shalhoub-Kevorkian and Suhad Daher-Nashif concluded that it was less culturally explainable as "honor crimes" than femicides in the context of the increasing spatial segregation of Palestinian communities and the restriction of living space by Israeli settler colonialism.

Shalhoub-Kevorkian has proposed an expanded definition of femicide: "Femicide is the process leading to death and the creation of a situation in which it is impossible for the victim to 'live'." (in the original "Femicide is the process leading to death and the creation of a situation in which it is impossible for the victim to 'live'.") Femicide, according to Shalhoub-Kevorkian, is the set of hegemonic male-social methods used to destroy women's rights, ability, and power to live safely. These methods include abuse, threats, assaults and attacks that degrade and humiliate women. This, she says, leads to constant fear, frustration, isolation and exclusion and takes away women's control over their intimate lives. In her view, femicide is not just a gender issue, but also a political issue.

Femicide in Latin America and the concept of feminicidio

→ Main article: Femicide in Latin America

In the 1990s, a movement against violence against women developed in Latin America in the course of which the term feminicidio was coined. The starting point was the struggles in Mexico, which the victims' relatives and activist groups led from 1993 onwards against the murders of women in Ciudad Juárez, a city in the state of Chihuahua on the border with the USA. Each year, several hundred women were abused and killed in this Mexican city. Authorities made little effort to solve the crimes. Only a few perpetrators were caught and convicted.

Activists who collected data on the murders from 1993 onwards published them from the beginning with the designation Femizid (Femicide). But the usual term was "las muertas" ("the dead women") and the slogan "Ni Una Más" ("Not One More") dominated demonstrations. After the discovery of the bodies of eight women in Ciudad Juárez in December 2001, who had been subjected to extreme abuse and torture before being murdered, what had been a national campaign against violence transformed into a transnational one. 300 local, national and transnational feminist and human rights organizations joined together to form a transnational network. The network built relationships with many international organizations, including AmnestyInternational, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, and the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women. Between 1998 and 2007, more than 24 reports and a total of 200 recommendations were published that identified women's discrimination and lack of equality as the main cause of violence against women in the Chihuahua region and the failure of Mexican institutions to prevent and punish it.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, several Latin American scholars and activists published reports and articles denouncing femicide in Latin America. In doing so, they translated the English term femicide sometimes as femicidio - which would be the direct translation - and sometimes as feminicidio. The feminist anthropologist and politician Marcela Lagarde justified the preference she gave to feminicidio by saying that femicidio was equivalent to homicidio (murder) and simply meant the murder of a woman.

In 2004, the Ni Una Más campaign organized a tribunal to raise awareness about the disregard for women's human rights in Chihuahua. Marcela Lagarde - modifying Diana Russell's concept of femicide - presented feminicidio as a state crime. The State does not protect women and does not create conditions to ensure the safety of women in public and private spaces. This is particularly serious, she said, when the State fails in its duty to ensure respect for the law. Activist groups in Mexico, and later throughout Latin America, seized on this new conception of feminicidio and used it as a framework for their campaign denouncing the failures of the Mexican state. Their goal was to shame and pressure the state at home and internationally.

Lagarde has complained that the term feminicidio is often used to refer to any murder of a woman, rather than accurately. In 2014, the Diccionario de la lengua española (Dictionary of the Spanish Language) included feminicidio with the explanation "murder of a woman because of her sex". This definition has been criticized as insufficient. In December 2018, the dictionary amended the explanation. It now reads "murder of a woman by a man because of machismo or misogyny".

United Nations involvement

The United Nations first appointed a UN Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and effects in 1994. In two reports, the first Special Rapporteur Radhika Coomaraswamy summarized in 1995 and 2002 that domestic violence was due to ideologies and cultural practices that fixed women to traditional role concepts. This legitimises violence and even "honour killings" against women who do not conform to these traditional ideas.

The 2012 report to the UN Human Rights Council by the Special Rapporteur Rashida Manjoo, who began work in 2009, was the first UN document ever to focus on femicide. She stated that gender-based female killings had reached alarming proportions. In the report, Manjoo emphasized as a conclusion that gender-based killings of women were not isolated phenomena that emerged suddenly and unexpectedly. Rather, they represented the tail end of a progression of gradually escalating violence. The report noted that the frequency of such killings was increasing worldwide.

On 25 November 2015, on the occasion of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, the new Special Rapporteur Dubravka Šimonovic called on all States to establish femicide watch. She suggested that femicide cases be broken down by age and ethnicity of victims and by gender of perpetrators, and that perpetrator-victim relationships be recorded. This data was to be published annually on 25 November, together with information on the prosecution and punishment of perpetrators. Three years later, she repeated the call. More than 20 countries have submitted reports to that effect, including Austria and Switzerland. In 2017, the UN established the web platform Femicide Watch, which provides information on definitions, studies and statistics on femicide.

Activities in Europe

A milestone for Europe with regard to violence against women was the adoption of the Istanbul Convention (Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence) by the Council of Europe in 2011, which created binding legal standards against violence against women and domestic violence. However, the Istanbul Convention does not explicitly address the issue of femicide.

The European Union initiated research programmes to develop a monitoring system for femicides so that targeted countermeasures could be taken, including in particular the programme "Femicide across Europe" (COST Action IS1206), which ran from 2013 to 2017. This programme, as well as the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), each use two definitions of femicide in parallel: a general definition and a definition for statistical purposes. The general definition draws on Diana Russell's definition that femicide is the killing of women and girls because of their gender. The EIGE limits the statistical definition of femicide to the killing of a woman by intimate partners or the death of a woman because of practices harmful to women.

According to activist Nursen Inal, Turkey has been struggling in vain for years to apply the Istanbul Convention. Thousands of women have lost their lives because of this. Turkey withdrew from the Istanbul Convention in 2021.

Marcela Lagarde, 2012

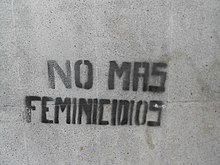

Graffito in Mexico City, 2011

Rashida Manjoo, UN Special Rapporteur, 2014

Murder in the House , 1890, by Jakub Schikaneder. Schikaneder painted this story of a woman's murder in the lower social classes on a canvas more than two metres high and three metres wide. In doing so, he placed the painting and its subject on a par with history paintings in terms of importance. These works are generally executed in large format because of their assumed importance to society.

Ceramic masks in honor of the women killed in or near Ciudad Juarez.

Typology

As the UN Special Rapporteur Rashida Manjoo outlined in 2012, femicide can be a direct killing - with specific perpetrators or perpetrators - or an indirect killing. Indirect killings include deaths due to poorly performed or clandestine abortions; increased maternal mortality due to violence perpetrated during pregnancy; deaths due to harmful practices such as female genital mutilation; deaths related to trafficking, drug trafficking, organized crime, and gang activity; the death of girls or women from neglect, starvation, or abuse; and intentional acts or omissions by the state.

Manjoo divided the direct killings according to the context of the killing. Here she named intimate partner violence, sorcery/witchcraft, "honour", armed conflict, dowry, gender identity and sexual orientation, and ethnic and indigenous identity. The WHO differentiates femicide into intimate femicide, homicide in the name of "honour", dowry-related femicide and non-intimate femicide.

Often femicides are subdivided according to the relationship between victim and perpetrator, such as by Diana Russell in 2008:

- Intimate femicide or intimate femicide: killing by intimate partner such as husband, life partner, boyfriend, sexual partner - each current or former

- Familial femicide: homicide by fathers, brothers, stepfathers, fathers-in-law, brothers-in-law, other male relatives

- Killing by other known perpetrators, for example, male family friends, male authority figures (teachers, priests, employers), colleagues.

- alien homicide

Search within the encyclopedia