Federal Reserve

![]()

Fed is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see FED.

The Federal Reserve System [ˈfɛdə˞əl rɪˈzɜ˞ːv ˈsɪstəm], often called the Federal Reserve or simply the Fed (as the Federal Reserve), is the central banking system of the United States.

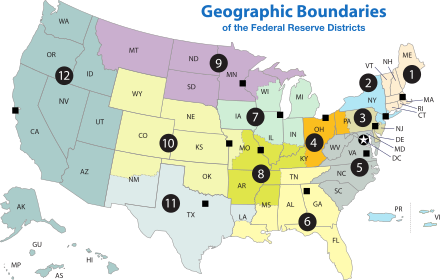

Founded in 1913, it was originally created as a system with a decentralized structure that would guarantee

a minimum reserve of gold at member banks, hence the name Federal Reserve System (German: 'Bundes-Reserve-System'). In order to achieve decentralisation, the territory of the USA was divided into twelve Federal Reserve Districts. In each of these districts a Federal Reserve Bank was established as a central bank. The Federal Reserve System has elements of both private and public law. It consists essentially of three institutions:

- the Board of Governors

- the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)

- the twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks

also from a large number of member banks (membership compulsory above a certain size).

The Federal Reserve sets monetary policy for the United States of America, supervises and regulates banks, maintains the stability of the financial system, and provides financial services to depository institutions, the U.S. government, and foreign institutions. The Fed reports regularly to the United States Congress on its monetary policy activities and plans. The Fed's day-to-day operations and operational decisions are determined independently. Congress can influence operations through legislation.

History

Predecessor

In 1781, the Bank of North America was chartered by the Continental Congress and began operations in Philadelphia on January 7, 1782. It was the first modern bank in the United States.

It was followed in 1790 by the First Bank of the United States on the initiative of the then US Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. The central bank was one of the reasons for the founding of the first political parties in the USA. The Federalists favored a national bank, while Thomas Jefferson's Republicans opposed it. The franchise of this first central bank in the United States expired in 1811 during the term of Democratic-Republican President James Madison and was not renewed.

Madison was forced by uncontrollable inflation at the end of 1815 to work out a compromise with Congress to stabilize the currency, which led to the establishment of the Second Bank of the United States in 1816. The Second Bank was largely similar to the First Bank in its mission and structure. However, the renewal of the Second Bank's charter was prevented by President Andrew Jackson's veto in 1832, and a slow process of dissolution began that came to an end when the charter expired in 1836.

In 1863 and 1864, based on the National Bank Acts, national banks were created, which were allowed to issue banknotes backed and printed by the US Treasury. The main goal of these laws was to create a single currency and solve the problem that banknotes from different member states were in circulation at the same time.

At the end of the 19th century, the American economy experienced one of the worst financial crises, due to bank failures and multiple monetary system fluctuations.

The proposal to establish a central bank on the European model came from the banker Paul Moritz Warburg of the Warburg banking dynasty in Hamburg. Paul M. Warburg was stunned by the primitive state of the American banking system after his arrival in New York in 1902. An acknowledged expert on national central banking in Europe, Warburg criticized the lack of a U.S. central bank and proposed the establishment of a private American central bank on the model of the German Reichsbank to take over monetary sovereignty from the state. In 1903, Warburg produced a paper entitled Plan for a Central Bank. Jakob Heinrich Schiff, Warburg's brother-in-law and senior partner at the leading Wall Street bank Kuhn, Loeb & Co. , took this expertise and presented it to his business partner James Jewett Stillmann, the chairman of the board of National City Bank (now Citibank), then the largest bank in the United States.

A few days later, Warburg and Stillman met and a confrontational conversation ensued. Stillman warned Warburg to show his expertise to anyone else, since the American people would strongly reject a central bank in which only a few could control everyone's deposits. The issue of establishing a central bank was part of the enduring domestic American conflict between proponents of central government power who wanted to expand the rights of the state as a whole (Federalists) and those who wanted to leave the observance and preservation of the laws to the individual U.S. states (Anti-Federalists). Warburg pointed out to Stillman that in the event of a panic in the financial markets, Stillman would regret the lack of a central bank, whereupon Stillman left the meeting with a grudge.

For years after reading Warburg's plea for a U.S. central bank, Jakob Schiff warned of the consequences of a financial crisis, letting the New York Chamber of Commerce know at a speech in early 1907: "If we do not get a central bank with adequate control over the raising of credit, this country will experience the sharpest and most profound monetary panic in its history." Already in the fall of that year, a temporary insolvency of the Knickerbocker Trust Company, New York's third-largest bank at the time, did indeed lead to a severe financial crisis, the Panic of 1907. The crisis forced Stillman to resign his position on the board of the National City Bank and, at the same time, gave new currency to Warburg's and Schiff's call for the establishment of a U.S. central bank.

As a result of the financial crisis, the US Congress decided after the end of the economic crisis to create framework conditions for a safer and more flexible banking system. Warburg was convened as an unofficial advisor to the newly formed National Monetary Commission, which drew up proposals for reforming the US banking system. The National Monetary Commission requested the creation of an institution that would manage the banks, control credit procurement, and prevent or mitigate financial and monetary crises. Paul M. Warburg published numerous newspaper articles and gave speeches on the need to establish a central bank. Another milestone in Paul M. Warburg's efforts was a 10-day meeting at the extremely elite Jekyll Island Club (owned by John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan) on Jekyll Island off the coast of Georgia in November 1910, where Warburg met with three other US bankers (Frank Vanderlip, Henry P. Davison, Arthur Shelton), the influential Senator Nelson W. Aldrich and Andrew Piatt, a leading economist from Harvard. The five other participants were initially skeptical of Warburg because of his status as a foreigner and a Jew, but he ultimately won them over with his brilliance. Over the next few days, a detailed and comprehensive plan for the creation of a U.S. central bank was devised, which, as the Aldrich Plan, initially resulted in the creation of the National Reserve Association. The secret of the participants as well as the purpose of the November 20-30, 1910 meeting on Jekyll Island was closely guarded until the 1930s.

The Federal Reserve System was created by the United States Congress to establish a "central banking system designed to add both flexibility and strength to the national financial system." The Federal Act was approved by Congress on September 18, 1913, by a vote of 287 to 85; the Senate, after several hearings, also approved it on December 19, 1913, by a vote of 54 to 34. Differences in the reconciled versions were revised by a joint commission; the revision was approved by Congress on December 22, 1913, by a vote of 298 to 60, and by the Senate the following day by a vote of 43 to 25, and was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on December 23, 1913, as the Federal Reserve Act. The Act provided for a system of several regional banks and a seven-member board of directors. Banks that operated on a national scale were required to join the Federal Reserve System; other banks were free to participate. Member banks received a fixed dividend of 6% for their shares, but did not share in the profits, which accrued to the Treasury.

Foundation 1913

The result of the efforts of central bank advocates was finally, after the election of Woodrow Wilson as U.S. president, the Federal Reserve Act of December 23, 1913, which sealed the creation of the U.S. central bank, the Fed, on the same day. The Federal Reserve Act had been preceded by a congressional investigation by Samuel Untermyer, the Pujo Money Trust Investigation. Untermyer, as an attorney part-owner of the law firm of Guggenheimer, Untermyer & Marshall, also assisted in drafting the Act. To this day, the Federal Reserve Act allows the Federal Reserve to create money with no intrinsic value as credit money and lend it, for example, to the U.S. government at interest. Paul Moritz Warburg, as a newly naturalized German Jew, declined the chairmanship of the Federal Reserve offered to him. Instead, Warburg became a member of the first Board of Governors in the history of the Fed. During World War I, Warburg was appointed vice chairman of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors on August 10, 1916. He served in this capacity until August 9, 1918, and remained associated with the Federal Reserve as a member of the Federal Advisory Council between 1921 and 1926.

Further developments

Banking Act 1933

Since the beginning of the Great Depression in the fall of 1929, there had been criticism of the Federal Reserve System as well as the economic policies of then-President Herbert Hoover, a Republican. It was also a campaign issue in 1932 and contributed to Roosevelt winning the presidential election in late 1932.

Originally, the heads of the regional banks were entitled to make decisions regarding Fed policy without regard to the decisions of the Board of Governors, which could lead to conflicts between the two parties. Roosevelt appointed Marriner S. Eccles; he helped draft the Emergency Banking Act of 1933, the Banking Act of 1933, and the Federal Housing Act of 1934.

In view of the economic situation (Great Depression), the Fed changed its monetary policy. Eccles drafted the Eccles Bill, which restructured the Federal Reserve System as the Banking Act of 1935. Eccles was appointed Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, a post he held until January 31, 1948.

The original Federal Reserve Act has been expanded or reformed several times over the years (notably in 1978 and 1981) to give the Fed more flexibility and functionality.

Banking Act 1935

The Banking Act of 1935 gave the Board of Governors broader supervisory powers. It was passed by Congress after the Emergency Banking Act on March 9, 1935. The Act included the following:

- The Federal Reserve banks were granted the authority to regulate the amount of loans approved by member banks on securities.

- Required the Board to supervise the foreign relations of Federal Reserve banks.

- Liberalized the rules for member banks to establish branches, primarily by eliminating or reducing previously defined geographical boundaries.

- Prohibited the associated banks from trading in securities and demanded that they be separated from associated companies that traded in the same securities.

- Prohibition on member banks paying interest on demand deposits.

- Required Federal Reserve banks to provide capital equal to one-half of their reserves for the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation.

- The Governing Board was given the power to regulate the interest rate on time and savings deposits in member banks.

- Provided security for bank deposits of $2,500 or more for a period of time.

The Fed also played an important role during World War II. Fed policy during wartime had two goals in particular:

- Keep interest rates low for the benefit of corporations and governments to finance war debts.

- Stabilisation of the monetary system due to seasonal fluctuations in deposits or unexpected withdrawals, also to increase safety in banking.

Federal Reserve Act 1977 and Humphrey-Hawkins Act 1978

The link between the Fed and the US Congress was relatively weak until the mid-1970s. This changed with the Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977 and the Humphrey-Hawkins Full Employment Act (signed and signed into law, respectively, by then US President Jimmy Carter in October). The Fed's independence was curtailed by these two laws; it was henceforth required to submit a binding report twice a year on its plans regarding the size of various monetary aggregates.

Federal Banking Agency Audit Act 1978

The Fed was not subject to external financial auditing by the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) until 1978. Until then, only the Fed's government financing activities were audited. Since 1978 (Federal Banking Agency Audit Act), GAO has been allowed to audit everything except the following:

- transactions for and with foreign central banks, governments or non-private international financial organisations

- monetary policy regulations, decisions and actions, including interest rates, minimum reserves and open market operations

- Transactions of the Open Market Committee

- Discussions and communications by central bank council members and Fed staff on items 1 through 3.

Monetary Control Act 1980

The Monetary Control Act, which became effective in June 1981, gave the Federal Reserve Banks, among other things, the authority to purchase not only U.S. government debt securities but also government debt securities of other countries.

Fed Headquarters: Marriner S. Eccles Federal Reserve Board Building, Washington, D.C., 2007

Organization

Structure of the Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System is composed of the following five components:

- board of governors

- 7 members, nominated by the President and appointed by the U.S. Senate, 14-year term.

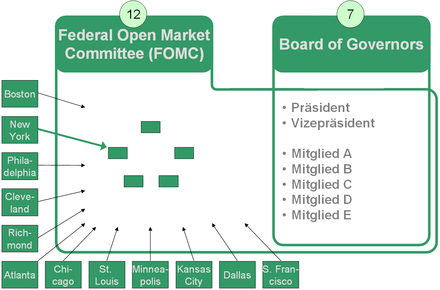

- Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)

- consists of the 7 members of the Board of Governors and the Presidents of the Reserve Banks

- Federal Reserve Banks (District Federal Reserve Banks)

- 12 regional Federal Reserve banks with 25 branches

- various advisory councils

- report to the Board of Governors and make recommendations to the Board.

- Member banks

The Federal Reserve System consists of twelve banking districts, each of which has a Federal Reserve Bank. The regional Fed banks are not financed directly by taxpayers' money, but mainly by interest income on the government bonds they hold and by loans to commercial banks. Each of these banks is funded by the financial capital of its private member banks. However, these are not shares traded on the market; rather, in the U.S., banks above a certain size are required by law to be members of the Federal Reserve System. The largest is the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in New York City, which is also the only one among them that conducts foreign business.

| Bank districts | Federal Reserve Banks | Branches | Websites | Presidents |

| 1 | Boston | http://www.bos.frb.org/ | Eric S. Rosengren | |

| 2 | New York City | http://www.newyorkfed.org/ | John C. Williams | |

| 3 | Philadelphia | http://www.philadelphiafed.org/ | Patrick T. Harker | |

| 4 | Cleveland | Cincinnati, OhioPittsburgh | http://www.clevelandfed.org/ | Loretta J. Mester |

| 5 | Richmond | Baltimore, MarylandCharlotte | http://www.richmondfed.org/ | Thomas Barkin |

| 6 | Atlanta | Birmingham, AlabamaJacksonville | http://www.frbatlanta.org/ | Raphael Bostic |

| 7 | Chicago | Detroit, MichiganDes | http://www.chicagofed.org/ | Charles L. Evans |

| 8 | St Louis | Little Rock, ArkansasLouisville | http://www.stlouisfed.org/ | James B. Bullard |

| 9 | Minneapolis | Helena, Montana | https://www.minneapolisfed.org/ | Neel Kashkari |

| 10 | Kansas City | Denver, ColoradoOklahoma | http://www.kansascityfed.org/ | Esther George |

| 11 | Dallas | El Paso, TexasHouston | http://www.dallasfed.org/ | Robert Steven Kaplan |

| 12 | San Francisco | Los Angeles, CaliforniaPortland | http://www.frbsf.org/ | Mary C. Daly |

Boards of the Federal Reserve System

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) conducts monetary and exchange rate policy in the United States; it is considered the Fed's most important committee.

Its chairmen were:

- Paul Volcker (from August 1979 to August 1987)

- Alan Greenspan (from 11 August 1987 to 31 January 2006)

- Ben Bernanke (from February 1, 2006 to January 31, 2014)

- Janet Yellen (from February 1, 2014 to. February 4, 2018).

Jerome Powell has been chairman of the Federal Open Market Committee since February 5, 2018.

The Board of Governors of the Fed is the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in Washington, D.C. It consists of seven members appointed by the President of the United States and elected for 14-year terms with the consent of the Senate. Members of the Board are not eligible for reelection immediately following their term of office. The Board consists of (as of December 18, 2020):

- Jerome Powell, President (since 2018)

- Richard Clarida, Vice President

- Randal Quarles

- Michelle Bowman

- Lael Brainard

- Christopher Waller

- unoccupied

The Board's task is to implement the decisions adopted by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Apart from its economic policy powers, the Board also appoints three directors for each of the twelve Federal Reserve Banks. The remaining six directors of each Federal Reserve Bank are appointed by the member banks.

As the Fed's most important body in terms of economic policy, the Federal Open Market Committee's (FOMC) tasks include conducting open market operations. The FOMC decides whether to change the key US interest rate (the target rate of the federal funds rate). In addition, the committee can also decide to intervene in the foreign exchange market, thereby affecting the exchange rate of the U.S. dollar against other currencies. Therefore, meetings of the FOMC and statements by its members are the object of public interest by financial markets.

The FOMC consists of twelve members: the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the seven members of the Board of Governors, and four members selected on an annual rotating basis from among the twelve Chairmen of the regional Federal Reserve Banks. For this purpose, eleven of the twelve banks are grouped by geography into four groups, each of which provides one member of the FOMC. Within the groups, there is rotation among the individual Federal Reserve Banks. For historical reasons, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York does not participate in this rotation process-it has a permanent vote on the FOMC. In addition, individual Reserve Bank presidents attend meetings but do not have voting rights. The committee meets eight times a year.

Under the Board's authority is the Federal Reserve Police.

State institution with private shareholders

The Federal Reserve System is a government institution, but it has private shareholders. It was established by federal law, so changes to its structure and functions can only be made by the legislature. It is true that the twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks are organized as corporations whose shareholders are the private banks operating in their districts. However, the shareholder rights in the case of the Federal Reserve Banks have little in common with those of private banks. The private banks are, by law, shareholders in the Federal Reserve Banks and have no free choice as to whether or how much to invest. Nor are shares in the Federal Reserve Banks transferable, unlike shares in stocks. However, the shares of the private banks that are shareholders in the twelve Federal Reserve Banks are freely transferable under private law, depending on their legal form. The members of the bodies that decide on the Fed's monetary policy are not elected by the shareholders, as would happen in a private joint stock company, but are appointed politically (nomination by the US President and confirmation by the Senate).

The distribution of the Fed's profits also differs considerably from that of private joint-stock companies; for example, the private banks that hold shares in the Federal Reserve banks receive a dividend that is fixed in advance by law. Any remaining profit goes to the US federal budget. In relative terms, dividends to shareholders are negligible; in 2011, for example, dividend payments to private banks amounted to $1.6 billion, while profit distributions to the federal budget totaled $78.4 billion.

In view of these differences from private corporations, the Federal Reserve System refers to itself as an "independent entity within the government". Federal courts have also ruled that the Federal Reserve Banks are federal instrumentalities.

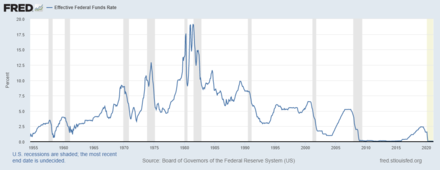

Fed Funds Rates since 1955 (blue line) and U.S. Economic Recession Periods (gray bars)

Boards of the Federal Reserve System

Banking districts of the individual Federal Reserve banks

Search within the encyclopedia