Fairy tale

![]()

This article is about fairy tales in general; for works with that title, see The Fairy Tale. For the German artist, life artist, graphic artist, painter, and poet, see Artur Märchen.

Fairy tales (diminutive of Middle High German mære = "tale, report, news") are prose texts that tell of miraculous events. Fairy tales are a significant and very old text genre in oral tradition (orality) and occur in all cultural circles. In contrast to the orally transmitted and anonymous folk tale is the form of the art fairy tale, whose author is known. In the German-speaking world, the term fairy tale was coined in particular by the collection of the Brothers Grimm.

Unlike the saga and legend, fairy tales are freely invented and their plot is neither fixed in time nor place. However, the distinction between mythological legend and fairy tale in particular is blurred, and the two genres are closely related. A well-known example of this is the fairy tale Sleeping Beauty, which Friedrich Panzer, for example, considers to be a fairy-tale "defused" version of the Brünnhilden saga from the circle of the Nibelungen saga. The Waberlohe can be seen as trivialized to a rose hedge and the Norns as fairies.

Characteristic of fairy tales is, among other things, the appearance of fantastic elements in the form of animals that speak and act like humans, of sorceries with the help of witches or wizards, of giants and dwarfs, ghosts and mythical creatures (unicorn, dragon, etc.); at the same time, many fairy tales bear social-realistic or social-utopian features and say a lot about social conditions, e.g. about domination and servitude, poverty and hunger, or family structures at the time of their creation, transformation or written fixation. After the folk tales had been written down, a diversification of media began (pictures, illustrations, translations, retellings, parodies, dramatizations, film adaptations, settings to music, etc.), which now took the place of oral transmission. In this respect, the "rescue" of fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm, for example, is on the one hand welcome, but on the other hand it also puts an abrupt end to the oral transmission of a mono-medial type of text.

Fairy tale telling has been recognised as an Intangible Cultural Heritage in Germany. The German UNESCO Commission included storytelling in the Federal Register of Intangible Cultural Heritage in December 2016.

Fairy Tale Research

Comparative Fairy Tale Research

Comparative fairy tale research was founded by the Brothers Grimm and continued by Theodor Benfey later in the 19th century. Many different fairy tales, even in storytelling traditions far removed from each other and across linguistic boundaries, show a striking amount of commonality in the smallest isolatable plot units. In 1910, Antti Aarne categorized fairy tales according to their essential narrative content; this gave rise to the Aarne-Thompson Index, which is still in use today in international narrative research. (In German, the abbreviation AaTh is often used to avoid confusion with AT for Old Testament). In 2004 Hans-Jörg Uther presented another revision. Since then, the classification has been kept as the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index, abbreviated ATU, and contains an extensive list of fairy tale types with systematic cataloguing of the plot units.

In 1928, the Russian philologist Vladimir Yakovlevich Propp made an important contribution to literary fairy tale research with his structuralist study of the morphology of the fairy tale. To this Eleasar Meletinsky added important insights into the demarcation of fairy tale and myth.

Psychological and psychoanalytical approaches

More recently, fairy tales have also been studied using various theoretical approaches from anthropology, oral history, psychology (analytical psychology, psychoanalysis, psychological morphology), and other individual disciplines. Among the most important psychological researchers of fairy tales are Marie-Louise von Franz and her student Hedwig von Beit. Von Franz published numerous monographs on psychological fairy tale interpretation. Her central thesis, following C.G. Jung, is that in fairy tales archetypal contents of the collective unconscious are represented with their processual interaction in the human psyche. Thus, fairy tales contain psychological orientation knowledge in symbolic form; historically, they have often had the function of compensating for the one-sidedness of collectively prevailing values and views. In Bruno Bettelheim's view, fairy tales make clear the difference between the pleasure principle and the responsibility principle; this is where their pedagogical effect lies.

One problem with psychological or psychoanalytic fairy tale interpretation is that rarely do two interpretations of a fairy tale agree. This indicates a lack of evidence. The Germanist and narrative researcher Lutz Röhrich shows this using the example of interpretations of the fairy tale of Rumpelstiltskin and states that the usefulness of the fairy tale that people remember or dream about is greater for the psychoanalyst than the usefulness of psychoanalysis for the fairy tale researcher. For each person a fairy tale offers different possibilities of association. Psychoanalysis tells us nothing about the origin, age, distribution and cultural-historical background of fairy tales. Röhrich therefore pleads for a pluralism of methods in the interpretation of fairy tales.

Structural analyses

Less speculative are approaches that examine the structure of fairy tales. All fairy tales, regardless of their content, are based on a fixed, usually very clear unilinear (single-stranded) plot structure. Typical is an occasionally two-part, but often three-part structure with heightening in the third period (e.g. three tasks, three brothers or sisters). This structure fulfils certain functions associated with "archetypal" actors (hero, antagonist, helper, etc.) and can already be found in antiquity.

Moral function of fairy tales

André Jolles rejects the classificatory and structuralist approaches that see fairy tales as mere sequences of typical narrative motifs. The fairy tale is also not a moral narrative in the sense of an ethics of action (why does someone do something? and is this a virtuous action or an expression of wickedness?). Rather, the "naïve" (pre-literary) form of the fairy tale serves moral expectations in the sense of an ethics of action: reading or listening to a fairy tale is satisfied when a situation that is perceived as unjust is changed in such a way that, according to this naïve feeling, the world should be, i.e. when the happiness of the disadvantaged exceeds that of the advantaged by as much as it was less at the beginning of the story. This does not mean that the advantaged are always evil by nature and the disadvantaged always good in the ethical sense, or that virtue is always rewarded and vice punished. It only means that the faltering sense of justice is brought back into balance by the course of events, and often without too much effort (e.g. with miracle machines). The abstractness of space and time and the namelessness, even interchangeability of most of the actors, who are "symbolic condensations" (Bernd Wollenweber), contribute to making individual motives for action recede into the background. If the narratives are set in space and time and furnished with concrete figures, as in the saga, the question of motive immediately arises, and with it the question of "good" or "evil" actions.

Typical of fairy tales are dichotomies. Good and evil usually appear as characters characterized as good or evil. Exceptions are, for example, ambivalent trickster characters or animals who are "good with the good and bad with the bad"; however, the inner world of the characters is rarely described. Their character is revealed only by their behavior. Usually the focus is on a hero or heroine who must face confrontations with good and evil, natural and supernatural forces. Often the hero is a superficially weak character such as a child or the disadvantaged youngest son. He or she also often embodies cleverness or cunning that must contend with a raw environment. Often the small, inconspicuous, weak, lowly one triumphs over the great, powerful, noble one, sometimes the stupid or naïve one who is fearless with stupidity and seizes his chance.

As a rule, fairy tales end with good being rewarded and evil being punished. This is especially true for fairy tales that have been adapted into literature. Here are two examples from the collection of the Brothers Grimm:

"And as he stood there, having nothing at all, the stars fell from heaven, and there were all the thalers; and though he had given away his shirt, yet he had on a new one, and that was of the very finest linen. So he gathered the thalers into it, and was rich all his days."

- The Star Money

"When the wedding was to be held with the king's son, the false sisters came, wanted to ingratiate themselves and take part in his happiness. When the bride and groom went to the church, the oldest was on the right and the youngest on the left, and the doves pecked out one eye of each of them. Afterwards, when they went out, the oldest was on the left and the youngest on the right, and the doves pecked out the other eye of each of them. So they were punished for their wickedness and falsehood with blindness for the rest of their lives."

- Cinderella

Or else the "evil consumes itself in itself" (Lüthi) like the witch in Hansel and Gretel through her gluttony.

European folktales

German fairy tales

In the German-speaking world, the term fairy tale is primarily associated with the folk tale collection Kinder- und Hausmärchen by the Brothers Grimm (1812), but there are numerous other collections of German folk tales, such as the Deutsche Märchenbuch by Ludwig Bechstein, the Deutsche Hausmärchen by Johann Wilhelm Wolf, or those by Wilhelm Hauff, known as Hauff's Märchen.

French fairy tales

In France, the first collection of fairy tales was created in 1697 by Charles Perrault's Histoires ou Contes du temps passé avec des moralités. Marie-Catherine d'Aulnoy also published a collection of fairy tales in eight volumes in 1697/98 (Les Contes des fées, Contes nouveaux ou Les Fées à la mode), which she admittedly embellished, provided with sentimental dialogues or even freely invented. She can thus also be counted among the early authors of art fairy tales, but coined the term contes de fée (fairy tales), from which the English fairy tales are derived, for the entire genre of fairy tales. The element of magic and fable is already apparent in the name. However, it is not only magical beings (of divine or devilish origin) that make the fairy tale world so fantastic, but also objects with magical effects that are of great use to the fairy tale heroes - apparently a legacy of Celtic mythology - or being enchanted into an animal or plant whose symbolic content can be questioned. Similarly, petrifactions play a role from time to time, which can be interpreted in the same depth-psychological way as the redemption through the tears of a compassionate person.

However, the French tales that have survived from the turn of the 18th century reflect the problems of a Malthusian society in which a famine crisis that has existed since 1690 leads to a decline in the birth rate, infanticide, and the neglect and abandonment and sale of children by parents and especially stepparents. There is also a theme of crippling by disease, accident or mutilation of family members deemed unproductive who become beggars. The fantastic elements of French fairy tales are far less pronounced than in German fairy tales; they are seldom set in the forest, but rather often in the household, in the village, or on the country road. Thus they show clear social-realistic traits: they show what is to be expected from life. Important themes are repeatedly hunger, the compulsion to live a de facto vegetarian life in which meat is a rare luxury, or the lower-class utopia of eating one's fill. The "search for happiness" on the country road is merely a euphemism for begging. However, fantasies of transformation (into animals, princes, etc.) also flourish, expressing the compulsion to escapism.

English Folktales

The oral tradition of folk tales in England shows far more optimistic and cheerful features than in France or Germany. Complete tales rarely survive, often only rhymes or songs, but they are about the same characters as the German or French fairy tales. After all, in 18th-century English agrarian society, hunger was hardly ever universal until early industrialization. In more recent times, Celtic and English folktales were collected by the Australian Joseph Jacobs.

Italian Fairy Tales

Here, too, the same characters and plots appear as in the French fairy tale. However, they are often shifted into the aristocratic or mercantile milieu and treated in a more comic-Machiavellian manner, as in the manner of the Commedia dell'arte, for example in the Pentamerone (1634-1636; first complete German edition 1846) by Giambattista Basile, from which Clemens Brentano and Ludwig Tieck retold some stories. The Pentamerone is the oldest European collection of fairy tales, although the frame story is also fairy tale-like. The material, baroqueized by Basile, derives from Neapolitan and Oriental lore as well as Greek mythology. The Brothers Grimm Jacob discovered in it many similarities with the orally handed down fairy tales collected by them, such as Cinderella.

Spanish fairy tales

Spanish fairy tales (cuentos populares) tell of the competition between a culturally and intellectually highly developed Moorish-Islamic culture and the militant, rather uncivilized Christian chivalry during the Reconquista. In this respect, they are more clearly set in a specific regional and temporal milieu than, for example, German fairy tales, and are more similar to sagas.

Russian fairy tales

Russian folk tales were collected by Alexander Nikolayevich Afanasyev; his collection, published between 1855 and 1863, is one of the largest in the world, containing some 600 fairy tales; the editing, however, was more careful than that of the German fairy tales by the Brothers Grimm. Apart from the magic fairy tales (e.g. about the figure of Baba Jaga with her chicken legs or about the beautiful and clever Wassilissa), there are mainly animal fairy tales, with the animals of the forest such as the fox, bear and wolf playing a leading role. However, they usually lack the directly instructive character that animal fables have; in moral terms, animals like the bear are often indifferent, in fact just unpredictable. Sometimes they protect the hero, sometimes they are dangerous predators. This also applies to the figure of the "witch" Baba Jaga.

Another pedagogical function of many Russian fairy tales is clearer than in German fairy tales: Through distinctive rhythms, frequent literal repetition and long enumerations (so-called "chain fairy tales" such as "The Kolobok" - known in the German-speaking world as the fairy tale of the "big fat pan cake"), they aim to strengthen the memory of the listener and put the memory to the test.

Other examples of European fairy tales

The defining figures of the Scandinavian fairy tale tradition are trolls, giants, pixies or protective household spirits. However, it also adopted Old Norse, ancient and Christian myths and legends and was also influenced by Germany. Norwegian folk tales were collected by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen.

Almost only insular Celtic myths and legends have survived from the Celts.

The Czech writer Božena Němcová (1820-1862), who is still popular today, became famous especially for her collection of fairy tales (American edition 1921). With her work, she also consciously laid the foundations of today's Czech language. Many of her fairy tales have also been made into films, and the fairy tale film Three Hazelnuts for Cinderella in particular has been part of the standard programming of German-language TV stations since 1973.

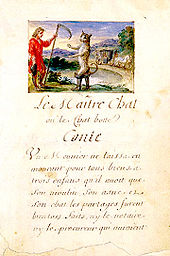

Puss in Boots, "Master Puss", manuscript page, France, late 17th century.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a fairy tale?

A: A fairy tale is an English language expression for a kind of short story. It has the same meaning as the French expression conte de fée or Conte merveilleux, the German word Märchen, the Italian fiaba, the Polish baśń, the Russian сказка or the Swedish saga. These stories usually involve fairies, goblins, elves, trolls, giants or gnomes and often contain elements of magic. They can also be used to describe unusual happiness and unbelievable stories.

Q: How are fairy tales different from legends and traditions?

A: Fairy tales are different from legends and traditions because they do not claim that their stories are true like legends and traditions do. Additionally, they usually do not specifically mention religion or actual places, people and events like legends and epics do.

Q: Where can we find fairy tales?

A: Fairy tales can be found in both oral form (passed on from mouth to mouth) and in literary form (written down). Literary works show that there have been fairy tales for thousands of years.

Q: Who wrote some new fairy tales?

A: New fairy tales were written by authors such as Hans Christian Andersen, James Thurber and Oscar Wilde. Examples include The Little Mermaid or Pinocchio.

Q: Are all fairy tale endings happy?

A: No, not all fairy tale endings are happy - though "fairy tale ending" is sometimes used to describe a happy ending even when it doesn't necessarily apply to a particular story.

Q: Are demons and witches seen as real in fairy tales?

A: Yes - where demons and witches are seen as real in certain cultures around the world, these characters may appear in some versions of traditional old fairy tales such as Sleeping Beauty or Little Red Riding Hood.

Search within the encyclopedia