European Union

![]()

EU is a redirect to this article. For other meanings of "European Union", "EU", "Eu" and "eu", see EU (disambiguation).

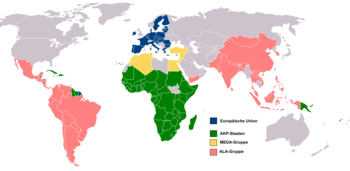

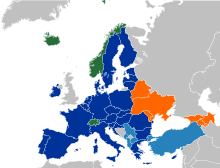

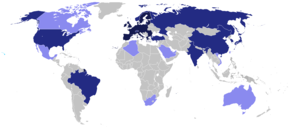

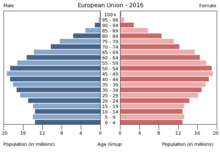

The European Union (EU) is an association of 27 European countries. Outside of geographical Europe, the EU includes Cyprus and some overseas territories. It has a total population of about 450 million. Measured by gross domestic product, the EU internal market is the largest common economic area on earth. The EU is a legal entity in its own right and therefore has the right to see and speak at the United Nations.

The most common languages in the EU are English, German and French. In 2012, the European Union was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

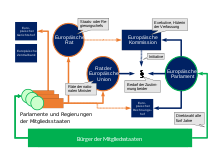

The political system of the EU, which has emerged in the course of European integration, is based on the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. It contains both supranational and intergovernmental elements. While the individual states are represented by their governments in the European Council and the Council of the European Union, the European Parliament directly represents the citizens of the Union in EU lawmaking. The European Commission as the executive body and the EU Court of Justice as the judicial body are also supranational institutions.

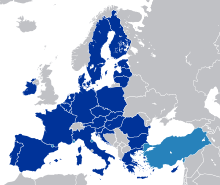

The beginnings of the EU date back to the 1950s, when initially six states founded the European Economic Community (EEC). Targeted economic integration was intended to prevent military conflicts for the future and, through the larger market, to accelerate economic growth and thus increase the prosperity of citizens. In the course of the following decades, additional states joined the Communities (EC) in several rounds of enlargement. Beginning in 1985, the Schengen Agreement opened internal borders between member countries. After the fall of the Iron Curtain and the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc in 1989, the geopolitical situation in Europe changed fundamentally, opening up opportunities for integration and expansion in the East.

The Treaty of Maastricht established the European Union in 1992, giving it powers in non-economic policy areas. In several reform treaties, most recently the Treaty of Lisbon, the supranational competences of the EU were expanded and the democratic anchoring of political decision-making processes at the Union level was improved, above all by further strengthening the position of the European Parliament. However, a European public sphere and identity as a prerequisite for supranational popular sovereignty is only gradually emerging, and not without countercurrents. Since the 1980s, the EU has been given more powers and has gained in importance. The constitutionality of the EU was debated; EU skepticism was also expressed. In 2007, the Treaty of Lisbon also regulated exit scenarios.

Of the 27 EU states, 19 form an economic and monetary union. In 2002, a common currency for these countries, the euro, was introduced. Within the framework of the area of freedom, security and justice, the EU member states cooperate on domestic and judicial policy. Through the common foreign and security policy, they strive to act together vis-à-vis third countries. Future-oriented joint action is the subject of the Europe 2020 initiative, which includes digital policy. The European Union has observer status in the G7, is a member of the G20 and represents its member states in the World Trade Organization.

In 2016, the EU was the world's second-largest economic area in terms of nominal gross domestic product (behind the USA) and purchasing power-adjusted gross domestic product (behind the People's Republic of China). As an association of states, it is the world's largest producer of goods and the largest trading power. Its member states have some of the highest living standards in the world, although there are significant differences between individual countries even within the EU. In the Human Development Index, 26 of the then 28 member states were considered "very highly" developed in 2015.

After the eastward enlargement in 2004 and 2007, the standard of living and economic growth have risen sharply, especially in Eastern Europe. At the same time, however, as a result of the financial crisis from 2007 and through the refugee crisis from 2015, the European Union has been exposed to increasing EU skepticism from parts of the population in various member states, which has been reflected, among other things, in the withdrawal of Great Britain. Under the impression of the crisis phenomena and the rise of right-wing populist tendencies in the member states of the Union, the EU finality debate is once again being intensively conducted. On the other hand, approval ratings for the EU are currently higher across Europe than they have been for decades. With his Initiative for Europe, French President Emmanuel Macron has presented a reform plan for the near future that has attracted a great deal of attention.

History

→ Main article: History of the European Union

Already after the First World War, there were various efforts to form a union of European states, such as the Paneuropa Union founded in 1922. However, these efforts were ultimately unsuccessful. The decisive starting point for European integration did not come until the end of the Second World War: By networking the militarily relevant economic sectors, a new war between the former adversaries was to be made impossible and, as a consequence, political rapprochement and lasting reconciliation between the states involved was to be achieved. In addition, security policy considerations were also important: In the incipient Cold War, the Western European states were to be brought closer together and the Federal Republic of Germany was to be integrated into the Western bloc.

Timetable

| Subz. | 19481948 | 19511952 | 19541955 | 19571958 | 19651967 | 19861987 | 19921993 | 19971999 | 20012003 | 20072009 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||

| European Communities | Three pillars of the European Union | ||||||||||||||||||||

| European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) | → | ← | |||||||||||||||||||

| European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) | Contract expired in 2002 | European Union (EU) | |||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| European Economic Community (EEC) | European Community (EC) | ||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

| → | Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) | |||||||||||||||||

|

| Police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters (PJZS) | ← | |||||||||||||||||||

| European Political Cooperation (EPC) | → | Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) | ← | ||||||||||||||||||

| Western Union (WU) | Western European Union (WEU) |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| dissolved as of July 1, 2011 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||

Coal and Steel Union (1951)

→ Main article: Coal and Steel Union

Jean Monnet, then head of the French Planning Office, voiced the proposal to place all Franco-German coal and steel production under a joint authority. French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman took up this idea and presented it to Parliament on May 9, 1950, which is why it went down in history as the Schuman Plan. This Schuman Plan led to the founding of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC, colloquially also "Coal and Steel Community") on April 18, 1951 by Belgium, the Federal Republic of Germany, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands. The institutions of this ECSC formed the core of what later became the EU: a High Authority with supranational powers (which later became the European Commission), a Council of Ministers as the legislative branch (now the Council of the EU), and a Consultative Assembly (later the European Parliament). However, the competences of the various bodies changed in the course of integration - for example, the Consultative Assembly still had hardly any say, whereas today the European Parliament has equal rights with the Council in areas where the ordinary legislative procedure applies.

Treaties of Rome (1957)

→ Main article: Treaties of Rome

On March 25, 1957, the so-called Treaties of Rome constituted the next step in integration. With these treaties, the same six states founded the European Economic Community (EEC) as well as the European Atomic Energy Community (EAEC and Euratom). The goal of the EEC was to create a common market in which goods, services, capital and labor could move freely. Through Euratom, there was to be a common development for the peaceful use of atomic energy.

The ECSC, EEC and Euratom each initially had their own Commission and Council. However, with the so-called Merger Treaty in 1967, these institutions were merged and now called the institutions of the European Communities (EC).

Alongside the stages of progressive integration, however, there were also setbacks and phases of stagnation. For example, the plan for a European Defense Community (EDC) failed in the French National Assembly in 1954. In the 1960s, Charles de Gaulle, as President of France, put the brakes on the Community's progress with the so-called empty chair policy and with his repeated veto of British accession to the EEC. Then, in the first half of the 1980s, it was British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher who prevented further progress in integration by calling for a reduction in British contributions. This phase of stagnant integration was also referred to as Eurosclerosis. Nevertheless, isolated declarations continued to promote the idea of European integration during this period, such as the document on European identity adopted on December 14, 1973, in which the nine member states of the European Communities declared their commitment to the "dynamism of European integration" and affirmed the "envisaged transformation of the totality of their relations into a European Union" as a common goal.

It was not until the end of the 1980s that integration regained momentum. With the Single European Act (SEA) in 1987, the EEC under Commission President Jacques Delors developed the plan for a single European market in which all national barriers to Europe-wide trade were to be overcome by January 1, 1993, through an approximation of economic law.

Maastricht Treaty (1992)

→ Main article: Treaty of Maastricht

The fall of the Iron Curtain, the associated loss of power of the communists in the Eastern Bloc together with the change of government system in the GDR, Poland, Hungary, the ČSSR as well as Bulgaria and Romania led to the end of the East-West confrontation and thus to the enabling of the reunification of Germany and to further integration steps: On February 7, 1992, the Maastricht Treaty establishing the European Union (EU) was signed. It entered into force on November 1, 1993. On the one hand, the treaty decided to establish an economic and monetary union, which later led to the introduction of the euro; on the other hand, the member states decided on closer coordination in foreign and security policy and in the area of home affairs and justice. At the same time, the EEC was renamed the European Community (EC), as it was now given responsibilities in policy areas other than the economy (such as environmental policy).

With the Treaty of Amsterdam (signed in 1997) and the Treaty of Nice (in force since February 2003), the EU's treaty structure was again revised to bring about better functioning of the institutions. Until the Lisbon Treaty, only the European Communities had legal personality, not the European Union itself. This meant that the EC could take generally binding decisions within the scope of its competences, while the EU merely acted as an "umbrella organization." In the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) in particular, the EU could not act as an independent institution, but always only in the form of its individual member states.

The end of the Cold War also brought the overcoming of the political division of Europe into focus for the EU. It had already grown from six to fifteen members through several rounds of enlargement (1973, 1981, 1986, 1995); now the Central and Eastern European countries that had previously belonged to the Eastern bloc were also to become part of the Union. To this end, the EU member states established the so-called Copenhagen accession criteria in 1993, defining freedom, democracy, the rule of law, human rights and fundamental civil liberties as the Union's core values. In 2004 and 2007, the two eastward enlargements finally took place, in which twelve new members were admitted to the EU.

New objectives for the internal development of the European Union were set in 2000 with the Lisbon Strategy, which was intended to take appropriate account of the challenges of globalization and a new, "knowledge-based" economy. The strategic goal for the coming decade was determined to be "to make the Union the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world - capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion." In its 2005 "mid-term review," the European Parliament also expressed confidence that the EU's Lisbon Strategy could serve as a model for economic, social and environmental progress in the world, within the framework of the global goal of sustainable development. The successor program to the Lisbon Strategy, Europe 2020, launched ten years later, formulated essentially similar goals.

Lisbon Treaty (2007)

→ Main article: Treaty of Lisbon

However, the enlargement rounds threatened to increasingly restrict the EU's ability to act politically: The first adjustment reforms took place - with the usual difficulties and compromises - in the agricultural sector, in regional structural support and in the modification of the British rebate. With regard to the institutional structure, however, they were only partially successful: The veto possibilities for individual member states could have blocked a large number of decisions. With the introduction of the enhanced cooperation procedure by the Treaties of Amsterdam and Nice, a way was developed to counteract such a blockade of European decision-making processes. Member states willing to integrate could now take deeper steps toward agreement in individual areas, even if the other EU states did not participate: The Schengen Agreement and monetary union served as models for this. However, this concept of a "multi-speed Europe" also met with criticism, as it threatened to divide the EU. Another problem was the efficiency of the European Commission's work: Until 2004, individual member states still had two commissioners, but after the eastward enlargement the number was reduced to one commissioner per country - yet the Commission grew from nine members in 1952 to 27 members in 2007.

At the Laeken Summit in 2001, the EU heads of state and government therefore decided to convene a European Convention to draw up a new basic treaty that would make the EU's decision-making procedures more efficient and at the same time more democratic. In October 2004, this constitutional treaty was signed in Rome. Among other things, it provided for the dissolution of the EC and the transfer of its legal personality to the EU, an expansion of majority decision-making, a reduction in the size of the Commission, and better coordination of the Common Foreign Policy. Ratification of the Constitutional Treaty failed, however, because the French and Dutch rejected it in a referendum. Instead, an intergovernmental conference in 2007 drew up the Treaty of Lisbon, which adopted the main content of the Constitutional Treaty. Ratification was planned by the 2009 European elections, and the Treaty of Lisbon entered into force on December 1, 2009.

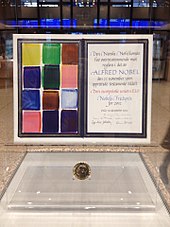

In 2012, the European Union was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize "for over six decades of contribution to the promotion of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe."

Phase of the challenges of the Union

Since the financial crisis from 2007 onward, which resulted in high levels of sovereign debt in some cases, and the ensuing euro crisis, the European Union has experienced economic and social turmoil among some of its members, which has in some cases strained the relationship between member states in need of financial assistance and those eligible for support measures. After 2010, a number of measures were initiated to address the euro crisis, including the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), established in 2012 as part of the euro bailout fund, and the European Fiscal Compact, which imposes fiscal discipline and debt limits on participating member states. The European Banking Union has transferred national competencies to central institutions as of 2014, creating uniform, common guidelines and regulations in the area of financial market supervision and the recovery or resolution of credit institutions within the European Union. Also, with the strengthening and sustained economic growth now of all member states after 2016, the European Union has begun to slowly overcome this crisis. Further institutional reforms such as a coordinated economic and social policy or the further development of the ESM into a European Monetary Fund are on the agenda of the EU in order to better and more quickly manage future crises or to prevent them from arising in the first place.

Disunity and further crisis-ridden developments in the European Union resulted in the refugee crisis from 2015 onward. In this overall context, anti-European political currents received further impetus. The refugee crisis is also seen as partly responsible for the United Kingdom's exit from the European Union. The willingness of the various governments of the member states to accept refugees varied greatly and stood in the way of joint action by the members of the Union to overcome the crisis, which was easily manageable for the Union as a whole. In some cases, border controls were reintroduced in the Schengen area; on the other hand, various arrangements were made to protect the EU's external borders, including the expansion of Frontex. A plan for the distribution of refugees among the member states was only rudimentarily implemented and was boycotted by national conservative governments, in part openly, contrary to majority decisions confirmed by the European Court of Justice. It is not only in this context that the European Union will soon have to decide what means it should use in the future to respond to open breaches of treaty by these governments, because the Treaty on European Union obliges the Member States of the European Union to show solidarity and uphold the rule of law (cf. Art. 2 TEU, Art. 3 TEU).

Global warming and bringing about effective climate protection are seen as a priority challenge for political action by the EU's newly elected institutions in 2019. On the occasion of the confirmation of the newly composed EU Commission by the European Parliament, President-elect Ursula von der Leyen issued the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the EU by 50 percent by 2030, rather than 40 percent as previously planned, as part of a "European green deal." Europe was to become the first climate-neutral continent. On the following day, November 28, 2019, the European Parliament declared a climate emergency for Europe. As a consequence, the European Commission is to align all its policies with the global goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees compared to pre-industrial times.

The certificate of the Nobel Peace Prize

Celebrations after the awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to the EU in 2012.

_edited.jpg)

The signatories of the Lisbon Treaty in 2007

The introduction of the euro as a standard currency in 1999, since 2015, the eurozone includes 19 member states.

The Treaty of Maastricht in 1992 establishes the European Union. (Place of signature)

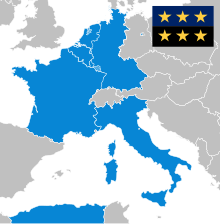

The six founding members of the ECSC in 1951 (Algeria was still part of France)

Hall and conference venue where the Treaties of Rome were signed in 1957

Political system

→ Main article: Political system of the European Union

The political system of the European Union clearly differs from national political systems. As a supranational association of sovereign states, the EU has its own sovereign rights, unlike a confederation of states; on the other hand, the EU institutions do not have competence competence - so unlike a federal state, the EU cannot shape the distribution of competences within its system itself. In accordance with the principle of conferral, the EU institutions may only act in those areas that are explicitly mentioned in the founding treaties. In its 1993 Maastricht ruling, the German Constitutional Court therefore coined the new term "association of states" to characterize the EU in terms of constitutional law.

The two most important treaties on which the EU is currently based are the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU; formerly the EC Treaty). They are therefore referred to as European primary law. All secondary law, which the EU itself enacts according to its own legislative procedures, is derived from these treaties and the competences mentioned therein. However, as a result of the legal personality that the EU has had since December 1, 2009, it can sign international treaties and agreements in its own name as a subject of international law (albeit in principle only by unanimous decision of the Foreign Affairs Council). Through the newly created European External Action Service, it can establish diplomatic relations with other states and apply for membership in international organizations - such as the Council of Europe or the United Nations.

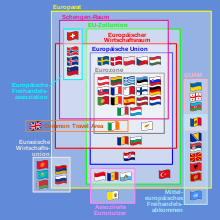

In addition to the EU, there is also the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), which is based on its own founding treaty concluded in 1958 (the Euratom Treaty). Following the dissolution of the ECSC and EC, Euratom is the last of the remaining European Communities. In its structures, however, it is fully affiliated with the EU and also shares its institutions with it.

Law

→ Main article: European law and legislation of the European Union

Depending on the policy area, the EU has different competences and voting procedures. In principle, legal acts adopted by the European institutions - Commission, Council and Parliament - in accordance with the EU's legislative procedures are binding. Since the governments of individual states can also be outvoted here, this is referred to as the supranational (supranational) community method. In some policy areas, such as trade policy, the vote is unanimous, but the decisions are binding and cannot be revoked by the individual states.

Other areas in which the EU has no legislative competence are characterized by purely intergovernmental (intergovernmental) decision-making mechanisms. This applies above all to the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP): Here, it is a matter of mere cooperation between the governments of the member states, whereby all decisions must be taken unanimously and also do not have immediate legal force.

Finally, the third method alongside the Community and intergovernmental methods is the open method of coordination, which is used in some areas for which the EU has no legislative competence of its own. Here, no formal decisions are taken, but only informal coordination of the member states in the Council; the Commission only acts in a supporting role.

The EU's supranational policy areas include, among others, the customs union, the European Single Market, the European Economic and Monetary Union, research and environmental policy, health care, consumer protection, areas of social policy, and the area of freedom, security and justice. The latter covers aspects of home affairs and justice policy, including immigration policy, judicial cooperation in civil matters, and police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters.

The supranational competences of the EU in this core area are evident in several ways:

- The Council of the European Union usually decides on the basis of the majority principle. The veto options of the individual member states are severely limited; in most policy areas, they can be outvoted by a qualified majority.

- The supranational European Parliament has full legislative rights in most policy areas. The governments of the member states cannot therefore legislate against the will of the Parliament.

- Certain executive activities in the EU are left entirely to the European Commission. This makes its independence vis-à-vis national governments particularly clear.

- EU law has a high binding effect: EU regulations are directly applicable law in all member states; in the case of EU directives, the member states are obliged to transpose them into the respective national law (even if the exact form is left to the individual states). The jurisdiction of the courts of the European Union with the European Court of Justice (ECJ) at its head is mandatory.

The European Commission (sole right of initiative), the Council of the European Union and the European Parliament are involved in the creation of EU legal acts in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure. A distinction is made between EU regulations (directly valid in the member states without a national act of transposition), EU directives (binding only after transposition into national law) and EU decisions (in each case a legal act in the individual case, similar to an administrative act).

Institutions

The institutional structure of the EU has remained essentially constant since its beginnings in 1952, although the competences of the individual institutions have changed several times. The legal basis for the institutions is Title III of the EU Treaty and Part Six of the TFEU.

In many respects, the EU displays typical features of a federal system, with the Commission as the executive and a two-part legislature consisting of the European Parliament as the chamber of citizens and the Council as the chamber of states. The important role of the Council is based on the concept of executive federalism, which also characterizes the Federal Republic of Germany. Compared with the practices in federal nation states, however, the influence of the lower level (in this case, the governments of the member states) is greater in the EU: For example, the members of the Commission are proposed by the national governments and the national parliaments are closely involved in EU policy through their EU committees. Another special feature is the European Council, the summit of heads of state and government that takes place every three months. According to the EU Treaty, this institution is to set the general political guidelines of the Union. It thus has a very great influence on the development of the Union, although it is not formally involved in its legislative process.

The central EU institutions:

|

European Parliament Legislature (Civic Chamber) |

European Council Sets guidelines and impulses |

Council of the European Union Legislature (chamber of states) |

European Commission Executive | |||

|

| ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Court of Justice of the European Union Judiciary |

European Court of Auditors Independent control body: Court of Audit |

European Central Bank Central Bank |

| ||

|

|

|

| ||||

|

|

|

European Council

→ Main article: European Council

The European Council (Art. 15 TEU and Art. 235 f. TFEU) is composed of the Heads of State or Government of the Member States and the President of the European Commission, with the President of the Commission acting only in an advisory capacity. It is chaired by the President of the European Council, who is appointed for a term of two and a half years. The European Council sets guidelines and objectives for European policy, but is not involved in day-to-day procedures. Votes in the European Council are generally taken "by consensus," that is, unanimously; only certain operational decisions are taken by majority vote. The European Council meets at least four times a year and generally convenes in Brussels.

Council of the European Union

→ Main article: Council of the European Union

The Council of the European Union (Art. 16 TEU and Art. 237 et seq. TFEU, also called the Council of Ministers) is one of the two legislative bodies of the EU and represents the member states (Länderkammer). Depending on the policy area, it is composed of the respective ministers of the national governments of the Member States and adopts the decisive legal acts together with the European Parliament. Depending on the policy field, either a unanimous decision or a qualified majority is required for this, whereby the principle of double majority (of states and inhabitants) applies for majority decisions. In intergovernmental areas, especially the Common Foreign and Security Policy and certain fields of trade and social policy, the Council is the EU's only decision-making body; here, decisions are generally taken unanimously.

The presidency of the Council rotates among the member states every six months, with three successive states working together in a so-called trio presidency. An exception is the Foreign Affairs Council, which is chaired by the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. The respective Council Presidency is supported by the General Secretariat of the Council of the European Union.

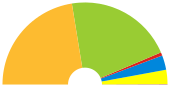

European Parliament

→ Main article: European Parliament

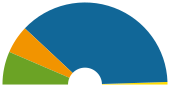

The European Parliament (EP, Art. 14 TEU and Art. 223 et seq. TFEU) is the second part of the EU legislature. In addition to its legislative function, it participates in the adoption of the budget and exercises parliamentary control rights. It has been directly elected by the citizens of the member states every five years in the European elections since 1979 and therefore represents the European population.

After the 2009 European election, the European Parliament initially had 736 members; as of December 2011, it was expanded to 754 (as of the 2014 European election: 751) members in accordance with the Treaty of Lisbon. These are not grouped according to national origin, but along their political orientation in (currently seven) political groups. For this purpose, national parties with similar world views have joined together to form European parties. The strongest group in the European Parliament is currently the Christian Democratic Conservative Group of the European People's Party (EPP/PPE) with 177 MEPs, followed by the Social Democratic Group Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament (S&D) with 146 MEPs (as of June 23, 2021).

However, the European elections will continue to be held on a national basis. The number of representatives per country is generally based on the size of the population; however, smaller countries are disproportionately represented in order to give them adequate representation of their national party landscape.

The European Parliament has two meeting places, one in Brussels and a second in Strasbourg. It is chaired by the President of the European Parliament (since 2019, the Italian David Sassoli, PES) and his deputies, the fourteen Vice-Presidents. Together they form the Bureau.

European Commission

→ Main article: European Commission

The European Commission (Art. 17 TEU and Art. 244 et seq. TFEU) has primarily executive functions in the institutional structure of the European Union and thus corresponds to the "government" of the EU. However, it is also involved in the legislative process: It has almost the sole right of initiative in EU lawmaking and accordingly proposes legal acts (directives, regulations, decisions). Parliament and the Council, however, are free to amend these proposals afterwards.

As an executive body, the Commission ensures the correct execution of European legal acts, the implementation of the budget and the adopted programs. As the "guardian of the treaties," it monitors compliance with European law and, if necessary, brings actions before the courts of the European Union. At the international level, it negotiates international agreements, especially in the areas of trade and cooperation, and represents the EU in the World Trade Organization, for example.

The European Commission consists of 28 commissioners, one from each member state. The European Council appoints them for five years by qualified majority. However, the European Parliament has a right of approval: it can reject the Commission-designate as a whole (but not individual Commissioners) and can also force it to resign after it has been appointed by means of a vote of no confidence. In this case, the European Council must propose a new Commission.

According to their treaty mandate, the Commissioners serve the Union alone and may not take any instructions. The Commission is therefore a supranational body of the EU, independent of the Member States. Within the Commission, each Commissioner assumes responsibility for a policy area, similar to the ministers in the cabinet of a national government. The political leadership of the Commission lies with the Commission President; from 2014 to 2019 this was Jean-Claude Juncker from Luxembourg, since then it has been Ursula von der Leyen.

The Commission has its own administrative apparatus, divided into departmental directorates-general, which, however, with approximately 23,000 civil servants, is significantly smaller than that of national governments. In addition, there are a number of European agencies that perform specialized tasks. As part of the executive branch, they are attached to the Commission, but functionally independent of it.

A special function is performed by the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (Art. 18 TEU), who is both a member of the European Commission and Chairman of the Foreign Affairs Council.

Following the 2019 European elections, Ursula von der Leyen was elected as the new President of the Commission, taking office together with her Commission, consisting of a coalition of EPP, S&D and RE, on December 1, 2019.

For the first time, this Commission has three so-called executive vice presidents and five other vice presidents. All vice presidents are responsible for a thematic focus of the von der Leyen Commission's political agenda in addition to their work as commissioners.

| Commission von der Leyen: | ||||||||||

| President | ||||||||||

| Office | Image | Name | Member State | national party | European Party | Group in the EU Parliament | Assigned Directorates General | |||

| President |

| Ursula von der Leyen | Germany | CDU | EVP | EVP | SG, SJ, COMM, EPSC | |||

| Executive Vice Presidents | ||||||||||

| Department | Image | Name | Member State | national party | European Party | Group in the EU Parliament | Assigned Directorates General | |||

| European Green Deal |

| Frans Timmermans | Netherlands | PvdA | SPE | S&D | CLIMA | |||

| Europe fit for the digital age (incl. competition) |

| Margrethe Vestager | Denmark Denmark | RV | ALDE | RE | COMP | |||

| Economy for the people |

| Valdis Dombrovskis | Latvia | Vienotība | EVP | EVP | FISMA | |||

| Vice Presidents | ||||||||||

| Department | Image | Name | Member State | national party | European Party | Group in the EU Parliament | DGs | |||

| Strengthening Europe in the world (EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy) |

| Josep Borrell | Spain | PSC | SPE | S&D | EEAS, FPI | |||

| Values and transparency |

| Věra Jourová | Czech Republic Czech Republic | ANO 2011 | ALDE | RE | ||||

| Promotion of the European way of life |

| Margaritis Schinas | Greece | ND | EVP | EVP | ||||

| Interinstitutional relations and foresight |

| Maroš Šefčovič | Slovakia | SMER | SPE | S&D | JRC | |||

| New momentum for European democracy |

| Dubravka Šuica | Croatia | HDZ | EVP | EVP | COMM | |||

| Other commissioners | ||||||||||

| Department | Image | Name | Member State | national party | European Party | Group in the European Parliament | Assigned Directorates General | |||

| Budget and administration |

| John Rooster | Austria | ÖVP | EVP | EVP | BUDG, HR, DGT, DIGIT, SCIC, OIB, OIL, PMO, OP, OLAF | |||

| Justice and the rule of law |

| Didier Reynders | Belgium | MR | ALDE | RE | JUST, IAT | |||

| Innovation and youth |

| Marija Gabriel | Bulgaria | GERB | EVP | EVP | RTD, EAC, JRC | |||

| Health |

| Stella Kyriakides | Cyprus Republic of | DISY | EVP | EVP | SANTE | |||

| Energy |

| Kadri Simson | Estonia | K | ALDE | RE | ENER | |||

| International partnerships |

| Jutta Urpilainen | Finland | SDP | SPE | S&D | DEVCO | |||

| Internal Market (incl. defense and space) |

| Thierry Breton | France | non-partisan | CNECT, GROW, new DG for defense | |||||

| Neighborhood and extension |

| Olivér Várhelyi | Hungary | Fidesz | EVP | EVP | NEAR | |||

| Trade |

| Phil Hogan | Ireland | FG | EVP | EVP | TRADE | |||

| Economy (incl. taxes and customs union) |

| Paolo Gentiloni | Italy | PD | SPE | S&D | ECFIN, TAXUD, ESTAT | |||

| Environment and oceans |

| Virginijus Sinkevičius | Lithuania | LVŽS | non-partisan | G/EFA | ENV, MARE | |||

| Jobs |

| Nicolas Schmit | Luxembourg | LSAP | SPE | S&D | EMPL | |||

| Equality |

| Helena Dalli | Malta | MLP | SPE | S&D | JUST, new task force for equality | |||

| Agriculture |

| Janusz Wojciechowski | Poland | PiS | EKR | EKR | AGRI | |||

| Cohesion and reforms |

| Elisa Ferreira | Portugal | PS | SPE | S&D | REGIO, new DG for structural reforms | |||

| Traffic |

| Adina Vălean | Romania | PNL | EVP | EVP | MOVE | |||

| Crisis management |

| Janez Lenarčič | Slovenia | non-partisan | ECHO | |||||

| Inner |

| Ylva Johansson | Sweden | SAP | SPE | S&D | HOME | |||

| ||||||||||

European Central Bank

→ Main article: European Central Bank

The European Central Bank (ECB, Art. 282 et seq. TFEU) has determined monetary policy in the euro area countries since January 1, 1999. The bank is politically independent: Its Executive Board is appointed by the European Council; however, it is not subject to political directives, but only to the monetary policy objectives laid down in the TFEU - in particular, the maintenance of price stability. An important steering instrument for this purpose is the setting of key interest rates. Together with the national central banks, the European Central Bank forms the European System of Central Banks (ESCB).

Court of Justice of the European Union

→ Main article: Court of Justice of the European Union

The Court of Justice of the European Union is the name given to the entire judicial system of the European Union (Art. 19 TEU and Art. 251 et seq. TFEU). The European Court of Justice (ECJ, officially just Court of Justice) is the supreme court of the European Union. In addition to the European Court of Justice, the European Court of First Instance (originally the European Court of First Instance) has existed since 1989. Both instances consist of at least one judge per Member State, with the ECJ additionally assisted by at least eight Advocates General (Art. 252). These are appointed by the governments of the Member States by consensus for a period of six years. Every three years, both instances are partially renewed. Since the Treaty of Nice, it has been possible to create independent specialized courts below the European Court.

The Court of Justice of the European Union is intended to ensure uniform interpretation of European Union law. It is empowered to rule itself in certain cases on legal disputes between EU member states, EU institutions, companies and private individuals. The progress of the European integration process has been promoted in part independently by the judgments of the ECJ, which has made the Community law for whose interpretation it is responsible directly applicable in the individual member states.

European Court of Auditors

→ Main article: European Court of Auditors

The European Court of Auditors (ECA, Art. 285 et seq. TFEU) was created in 1975 and is responsible for auditing all the Union's revenue and expenditure and for checking the legality of its financial management.

The European Court of Auditors currently has 27 members, one from each Member State, appointed by the Council of the European Union for six years. The ECA's current staff of about 800 form audit teams for specific audit projects. They can make audit visits at any time to other institutions, to Member States, and to other countries receiving EU aid. However, the ECA cannot impose legal sanctions. Violations are reported to the other institutions so that appropriate action can be taken.

The ECA's work reached wide publicity in 1998 and 1999, when it denied the European Commission a Statement of Assurance. However, the subsequent resignation of the Santer Commission should not be understood as an immediate reaction to the Court of Auditors' report; since the Court of Auditors has been issuing statements of assurance (since the early 1990s), they have always been negative.

Other facilities

The Committee of the Regions (CoR), based in Brussels, has represented regional and local authorities in the EU since its establishment in 1992. It has an advisory role in the legislative process and must be consulted in particular before decisions are taken that affect regional and local government. Of the 344 members of the CoR, 24 come from Germany, of which 21 are proposed by the federal states and three by the municipalities. Austria provides twelve members, nine of them representatives of the federal states and three of the municipalities.

The European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) is a body that has existed since 1957. It is supposed to represent "organized citizenship" (on the model of the French Economic and Social Council); its 344 members are composed of one-third each of employers' and trade union representatives and representatives of other interests (such as agriculture, environmental protection, etc.). They are appointed by the governments of the member states, but are not accountable to them. Like the CoR, the EESC acts only in an advisory capacity, but must be consulted on all matters of economic and social policy.

The European Ombudsman, based in Strasbourg, is the Ombudsman of the European Union and has been investigating complaints about maladministration in its institutions, bodies, offices and agencies since 1992.

The European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) is an independent supervisory authority of the European Union, established on the basis of Regulation (EC) No. 45/2001 (Data Protection Regulation) to provide data protection advice and supervision to the EC institutions and bodies. It is based in Brussels and has been a member of the International Conference of Data Protection and Privacy Commissioners since 2004.

The European Investment Bank (EIB; Art. 308 et seq. TFEU), headquartered in Luxembourg, was established in 1958. The bank is also politically independent and finances itself by borrowing on the capital markets. The EIB supports the Member States and smaller companies by granting loans to finance projects that are in the European interest, such as infrastructure projects or environmental protection measures.

The INTCEN, based in Brussels, is not an official body of the EU, but has recently been seen in some quarters as the nucleus of a cross-EU intelligence service.

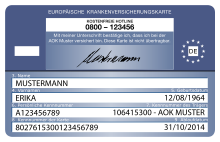

Citizenship of the Union

→ Main article: Citizenship of the Union

Citizenship of the European Union is held by all nationals of a Member State of the European Union according to Article 20 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). From the citizenship of the Union follows a number of rights of citizens of the Union, especially in the other Member States of which they are not nationals.

Rights include, in particular: Freedom of movement, prohibition of discrimination, right to vote in local elections in the place of residence, right to vote for the European Parliament, diplomatic and consular protection, right to petition and complain, and the right to communicate with the EU in one of the official languages of the European Union and to receive a reply in the same language. The Lisbon Treaty also introduced an instrument of direct democracy for the first time in the form of the European Citizens' Initiative.

Budget

→ Main article: Budget of the European Union

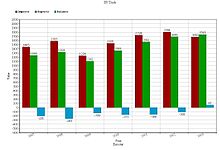

In the budget of the European Union, the revenues and expenditures are determined annually for the following EU budget year. The budget is integrated into a system of a so-called multi-year financial framework (MFF) that has been in place since the Treaty of Lisbon came into force on December 1, 2009. The European Union sets the binding financial framework for the budget in a multi-year period. It is agreed on the basis of a proposal by the European Commission by the Council, which in this case decides unanimously, together with the European Parliament, and transferred into a so-called interinstitutional agreement.

To finance its expenditures, the European Union has so-called own resources, which consist of contributions from the member states and, to a lesser extent, import duties at the external borders. The contributions of the member states result, on the one hand, from a share of the sales tax that must be paid to the EU (so-called VAT own resources) and, on the other hand, from contributions that are proportional to the gross national income (GNI) of the states. The so-called British rebate was an exception to this: Since a very large share of EU funds is spent on the Common Agricultural Policy, from which the United Kingdom benefited only slightly due to its comparatively small agricultural sector, it has been refunded two-thirds of its net contributions since 1984.

The EU budget and the level of contributions to be paid by the member states are the subject of many disputes and compromises, especially since the return flows of EU financial resources to the individual member states vary. In the European Council, therefore, the camps of net contributor and net recipient states are opposed to each other: While the net recipients mostly strive to maintain their status, the net payers try to at least reduce their payments.

Equally controversial is the expenditure side of the budget, although around 90% of this flows back to the member states. Within the framework of regional structural support, the EU strives to equalize the level of living in its member states. The flow of funds to the 271 regions into which the territory of the EU is divided (so-called NUTS 2 level) is based on per capita gross domestic product (GDP); the 99 regions in which GDP is below 75 % of the EU average from 2000 to 2002 receive higher allocations. However, because the rest of the budget is spent on a policy-area basis and not on a country-by-country basis, the net ratio of EU funds does not necessarily depend on a country's GDP: Ireland, for example, was a net recipient until 2009, despite having the second-highest average income in the EU after Luxembourg. Subsidies under the Common Agricultural Policy account for a large share of this policy area-specific spending.

The Multiannual Financial Framework as a financial planning instrument is drawn up for seven years at a time. The budgetary resources earmarked therein for the years 2007-2013 amount to around 975 billion euros, corresponding to 1.24% of the gross national income of all member states. This amount corresponds to the permissible ceiling set by the Council of the EU in the so-called Own Resources Decision. Within the financial framework, an annual budget is established with the Parliament and the Council acting jointly as the EU's budgetary authority: Both institutions can make amendments to the preliminary draft budget proposed by the Commission, with the Council having the final say on revenue and the Parliament on expenditure.

| Multi-year financial framework in € million | ||||

| Category | 2007–2013 | 2014–2020 | Comparison absolute | Comparison in % |

| 1. sustainable growth | 446.310 | 450.763 | +4.453 | +1,0 % |

| 1a. Competitiveness for growth and employment | 91.495 | 125.614 | +34.119 | +37,3 % |

| 1b. Cohesion for growth and employment | 354.815 | 325.149 | −29.666 | −8,4 % |

| 2. preservation and management of natural resources | 420.682 | 373.179 | −47.503 | −11,3 % |

| of which market-related expenses and direct payments | 336.685 | 277.851 | −58.834 | −17,5 % |

| 3. citizenship, freedom, security and justice | 12.366 | 15.686 | +3.320 | +26,8 % |

| 4. the EU as a global partner | 56.815 | 58.704 | +1.899 | +3,3 % |

| 5. management | 57.082 | 61.629 | +4.547 | +8,0 % |

| 6. compensation payments | - – | 27 | +27 | +100 % |

| Total commitment appropriations | 994.176 | 959.988 | −34.188 | −3,5 % |

| Commitment appropriations as a percentage of GNI | 1,12 % | 1,00 % | ||

In the Multiannual Financial Framework for the years 2014-2020, 39 percent of the total funds are earmarked for the Common Agricultural Policy; 34% is allocated to EU structural policy, 13% to research and technology, 6% each to foreign policy and administration; 2% is set aside for the fields of European citizenship, freedom, security and justice. The European Council reached a political agreement in February 2013 that the expenditure ceiling for the European Union for the period 2014-2020 is 959,988 million euros in commitment appropriations. This corresponds to 1.00% of the EU's gross national income.

.jpg)

Commission PresidentUrsula von der Leyen

Political system of the European Union: the seven institutions of the EU in dark blue.

.jpg)

President of the European CouncilCharles Michel

.jpg)

President of the European Central BankChristine Lagarde

The EESC is based in Brussels

Common passport design of the EU members

Burgundy red, Member State name and coat of arms, European Union title and biometric passport symbol

Expenditure shares in the 2007-13 MFF: Sustainable growth Natural resources Citizenship, Freedom, Security, Justice The EU as a global partner Management Compensation payments

Origin of EU revenues (2011): Traditional own funds: 13 % Value added tax own resources: 11 GNI own resources: 75 Other income: 1%

Parliament PresidentDavid Sassoli

Policies

All competences not conferred on the European Union in the Treaties remain with the Member States in accordance with Article 5 TEU. According to the principle of conferral, the Union shall act only within the limits of the competences conferred upon it by the Member States in the Treaties to attain the objectives set out therein. In accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, the Union shall take action in areas which do not fall within its exclusive competence only if and insofar as the objectives pursued can be better achieved at Union level than by the Member States. At the same time, EU action may not go further than is necessary to achieve the objectives set out in the EU Treaty (principle of proportionality). Despite these restrictive principles, EU legislation also determines a large part of national legislation: In the Federal Republic of Germany, for example, two-thirds of all laws passed in the area of domestic policy can be traced back to initiatives or legal acts at the EU level.

The Treaties confer on the Union either exclusive competence in a given area, or competence shared with the Member States. In certain areas, the Union also has competence only to implement measures to support and coordinate the actions of the Member States (supporting competence). According to Art. 3 TFEU, the Union has exclusive competence in the areas of the European Customs Union, the definition of competition rules for the European Single Market, the monetary policy of the states participating in the European Monetary Union, the conservation of marine biological resources under the Common Fisheries Policy, and the Common Commercial Policy. The shared competences according to Art. 4 TFEU include the European internal market, certain areas of social policy, economic, social and territorial cohesion, agriculture and fisheries with the exception of the conservation of marine biological resources, environmental policy, consumer protection, transport policy, trans-European networks, energy policy, the area of freedom, security and justice, certain areas of health protection, research, technology and space policy, and development policy.

![]()

Policy areas of the European Union

Responsibilities under the EU Treaty: Common Foreign and Security Policy | Common Security and Defense Policy. Competences under TFEU: Internal Market | Customs Union | Capital Markets Union | Agricultural and Fisheries Policy | Area of Freedom, Security and Justice (includes policies on border controls, asylum and immigration, judicial cooperation in civil matters, judicial cooperation in criminal matters, police cooperation) | transport policy | competition policy | approximation of laws | economic and monetary union | employment policy | social policy | education policy | sports policy | cultural policy | gender equality policy | health policy | consumer protection policy | trans-European networks | industrial policy | regional policy | research policy | environmental policy | energy policy | tourism policy | humanitarian aid and civil protection | administrative cooperation | trade policy | development policy.

See also: Political System of the European Union, Treaty on European Union, and Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

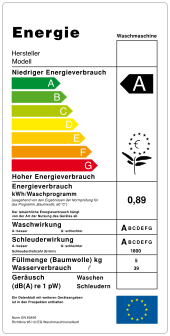

Economic policy

The history of European unification is characterized by the overriding importance of economic integration steps. Initiated by the communitarization of the coal and steel sector in 1952 and continued with the creation of the EEC and EURATOM in 1957 and the completion of the single market in 1993, they led up to the introduction of the euro as cash in 2002.

Today, the institutions of the EU play an important role in European economic policy in several areas: While the agricultural sector is characterized by an EU-wide market organization with high subsidies, the influence of the Union in industry and trade is particularly evident in the specification of standards and competition rules, compliance with which is monitored by the Commission. The main competence for ensuring fair competition on the internal market lies with the Competition Commissioner of the European Commission, who complements the respective antitrust authorities of the individual states as a supranational body. In addition to controlling the economy, he is also responsible for approving subsidies in the member states. This is intended to prevent individual states from supporting national companies to the detriment of competitors from the rest of the EU.

To strengthen European industry, the EU promotes new technologies. For example, numerous coordination bodies have been set up to develop uniform standards so that the internal market is not hampered in its development by differing technical standards.

In addition, the EU promotes, among other things, the cooperation of small and medium-sized enterprises in particular in the research and development of innovative products for growth markets. Externally, too, the EU countries act as a unified economic bloc and are represented by the Trade Commissioner in the World Trade Organization, for example.

Customs union and internal market

→ Main article: European Customs Union and European Single Market

The 1957 EEC Treaty aimed to remove barriers to trade between the Member States and provided for the gradual introduction of the so-called four fundamental freedoms, namely the free movement of goods, capital, services and labor within the territory of the Community. Of particular importance is the free movement of goods (Art. 28 et seq. TFEU), which prohibits import and export duties as well as quantitative import and export restrictions (quotas) within the internal market. Since the 1980s, the fundamental freedoms have been extended - inter alia by the case law of the ECJ and by the Single European Act - so that all other national standards that impede interstate trade within the Community are also prohibited. The economic community was thus expanded into a single internal market.

Since 1968, a customs union has been in force within the European Union, which means that trade between different member states may not be hindered by customs duties or levies having the same effect. In addition, the member states have a common customs tariff vis-à-vis third countries. Turkey has also been a member of the customs union since 1996, as have Andorra and San Marino. The EEA member states Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway form a free trade area with the customs union, but do not apply the common customs tariff vis-à-vis third countries.

Furthermore, Art. 34 et seq. TFEU generally prohibit quantitative restrictions on imports and exports between EU member states. Such restrictions are only permissible if such national legislation is necessary to protect public safety and order, for reasons of morality and public health, for reasons of the protection of human, animal and plant life or for the preservation of national treasures of artistic, historical or archaeological value or for the protection of industrial property. A general prohibition of discrimination also applies throughout the EU, according to which no EU citizen may be discriminated against on the basis of his or her citizenship. With regard to this so-called equal treatment of nationals, for example, merchants who sell goods in another EU member state may not be subject to any regulations other than those applicable to nationals of the state in question.

The case law of the European Court of Justice on the free movement of goods has made this fundamental freedom the driving force behind further market integration. The free movement of goods has been significantly expanded by the fact that goods-related regulations of the member states that treat EU foreigners in the same way as nationals and do not provide for quotas are also considered impermissible if they actually make trade in goods between the member states more difficult. According to the ECJ, such provisions have the same effect as quotas and are therefore equally contrary to the Treaty. This also applies to provisions that apply equally to nationals and foreigners: For example, the regulation has fallen according to which only beer brewed according to the German Purity Law could be sold in Germany. Since the purity law applied to both German and foreign producers, it was not disadvantageous, but it was practically tantamount to a ban on imports into Germany for beers produced outside Germany. However, national regulations that inhibit trade are permitted in cases where quantitative import and export restrictions would also be allowed. Furthermore, such regulations are permissible if they are not product-related but distribution-related.

With the Single European Act in 1986, the goal of a common internal market was also enshrined in the treaty. To prevent the principle whereby products that can be manufactured and sold in one EU member state cannot be banned throughout the rest of the Union from leading to a race to undercut production standards, the member states harmonized many of their legal and administrative regulations and created a large number of EU-wide standards in the Council of the European Union - despite criticism of the centralization this would entail.

Competition policy

In order to prevent economic cartels and monopolies in the EU and to ensure fair competition on the internal market, the antitrust authorities of the individual states are supported by the Competition Commissioner of the European Commission. In addition to controlling the economy, he is also responsible for approving subsidies in the member states. This is to prevent individual states from supporting certain companies in an anti-competitive manner. Subsidies are only permitted for economically weak regions (such as eastern Germany).

EU competition policy (Articles 101 et seq. TFEU) has played a major role in forcing many monopoly-like companies, for example in the telecommunications sector, in gas, water and electricity supply and in rail transport, to give up their special position and face competition from other providers on the market. The pressure of competition often led to spurts of innovation and to falling consumer prices, but also to changes in wage and working conditions and, in many cases, to job cuts at the companies concerned. Liberalization was and is therefore viewed critically in parts of the public.

Free movement of services

While the reduction of barriers to trade in goods progressed quite rapidly after the establishment of the common internal market, barriers to interstate trade remained in the services sector (Art. 56 et seq. TFEU) for some time. This problem area was addressed by the European Services Directive of December 12, 2006, which is considered by the European Commission to be an important component of the Lisbon Strategy for promoting the European economy. As a directive, it requires transposition into national law by the individual member states.

The aim of the directive is to promote cross-border trade in services. To this end, it provides for certain facilitations for established service providers, including the creation of single points of contact and electronic processing. Its scope covers not only traditional service providers such as hairdressers, IT specialists, service providers in the construction industry and craftsmen, but also in part services of general interest such as care for the elderly, childcare, facilities for the disabled, home education, waste collection, transport systems, etc., insofar as these are already provided under market conditions in the Member State concerned.

European Economic and Monetary Union

→ Main article: European Economic and Monetary Union

The introduction of a common European currency (Art. 127 et seq. TFEU) was a topic of discussion in the European Economic Community at an early stage. After initial attempts in this direction, such as the Werner Plan of 1970, failed, the euro was finally introduced as a common currency on the basis of the Maastricht Treaty: in 1999 for central and commercial banks, and in 2002 as a means of cash payment in all participating member states.

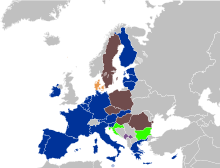

However, not all EU member states are members of the monetary union. During the negotiations, Great Britain and Denmark reserved the option of non-participation, which they have made use of to date. All other states are in principle obliged to participate, but this is subject to the achievement of certain conditions that are regarded as crucial for monetary stability. These so-called convergence criteria are laid down in the Stability and Growth Pact and relate to government debt, interest rate levels and inflation rates. Sweden is currently avoiding participation in monetary union by deliberately failing to meet these convergence criteria, as a referendum in 2003 decided against the euro. Of the new countries that joined in 2004, 2007 and 2013, Slovenia, Malta, the Republic of Cyprus, Slovakia, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania have so far participated in the monetary union. As a result, the euro zone has comprised 19 member states since 2015.

Even before the introduction of the euro, the convergence criteria led to a degree of harmonization in the financial and economic policies of the member states that was hardly expected. The governing body of the monetary union is the European Central Bank, which was set up independently on the model of the German Bundesbank. The coordination of the economic and financial policies of the member states is the responsibility of the so-called Eurogroup, in which the finance ministers of the euro zone meet.

Trade Policy

→ Main article: Common commercial policy

In the course of the Common Commercial Policy, the EU regulates imports and exports from and to third countries (Art. 206 f. TFEU). The Customs Union introduced a single customs tariff (TARIC, Combined Nomenclature), which is adopted by the Council of the European Union by qualified majority on a proposal from the Commission. It represents an important feature and bargaining chip of EU economic policy.

In principle, the EU's common trade policy is committed to the idea of global free trade, but it can draw on a comprehensive range of protective instruments of both a tariff and non-tariff nature to avert economic threats. In addition to autonomous measures, international trade agreements to which the EU is a party are also of great importance, especially those within the framework of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Although all member states are also independent members of the WTO, the spokesperson for them here is the European Union, represented by the European Commission's Trade Commissioner.

Agricultural and fisheries policy

→ Main article: Common Agricultural Policy and Common Fisheries Policy

Despite its comparatively small contribution to the EU's gross domestic product, agricultural policy (Art. 38 et seq. TFEU) acquired a prominent role in European integration at an early stage. Initiated by the European Commission in 1960, the first common agricultural market organization was introduced by the Council of Ministers in January 1962. The aim was to increase agricultural productivity and avoid price fluctuations, which would ensure a decent standard of living for producers and a stable supply at reasonable prices for consumers.

However, a system of guaranteed prices set up for this purpose had a large number of undesirable side effects. On the one hand, it led to production surpluses that were not in line with the market, and on the other hand, it resulted in food prices that were significantly higher than the world market level, thus burdening consumers. Moreover, since the European Economic Community guaranteed the purchase of production surpluses, its budget was also heavily burdened for decades: For a long time, agricultural policy accounted for well over half of total spending. In addition, the guaranteed price system also had negative consequences in terms of environmental and development policy, as it made imports more difficult. Under certain conditions, agricultural products can be produced more efficiently in emerging and developing countries. In addition to economic conditions such as wage levels and transport costs, climatic conditions and resource availability - particularly with regard to water and arable land - are also key factors here. Until the 1990s, all attempts at reform to reduce price subsidies failed due to drastic forms of protest by farmers and the unanimity principle retained here in the Council of the European Union.

Only when it became clear that the planned eastward enlargement would bust the EU budget without a reform of agricultural policy, since the economies of many of the accession candidates were still heavily agricultural, was a reduction in producer prices (with compensatory payments) and an approximation to world market prices for agricultural products initiated in the course of Agenda 2000, following various quota regulations. However, this reform process of the Common Agricultural Policy has not been completed to date.

| Overview of reforms of the Common Agricultural Policy | ||

| Year | Reform | Targets |

| 1968 | Mansholt Plan | Reduce the farm labor force by about half over a ten-year period and encourage larger, more efficient farms |

| 1972 | Structural measures | Modernization of agriculture, combating overproduction |

| 1985 | Green Paper "Prospects for the Common Agricultural Policy | Combating overproduction, also in 1985 enactment of a regulation to improve the efficiency of the agricultural structure. |

| 1988 | "Guideline for agricultural spending" | Limitation of agricultural spending |

| 1992 | MacSharry Reform | Basic reform with the objectives: Reduction of agricultural prices, compensation for income losses incurred, |

| 1999 | Agenda 2000 | Strengthening competitiveness through price reductions, rural policy, promotion of environmental measures and food safety. |

| 2003 | Mid-term review | Decoupling direct payments from production and tying them to cross compliance. |

| 2009 | "Health Check" reform | Accelerate Agenda 2000 measures while limiting EU agricultural spending. |

| 2013 | CAP reform 2013 | Greening, abolition of the last remaining export subsidies, direct payments |

While forestry has hardly played a role at the EU level so far, the Common Fisheries Policy (Art. 38 et seq. TFEU) has been an important bone of contention in negotiations and in the balancing of political compromises in the Council of the European Union since the early 1970s, although it accounts for only a small part in the EU budget. In 2004, the budget of the fisheries policy was 931 million euros, or about 0.75% of the total EU budget. The task of the Common Fisheries Policy is to promote the fishing industry in accordance with the principle of sustainability. To counter overfishing and the decline in fish stocks, the EU sets fishing quotas for the various member states and certain fish species. As part of its structural policy, the EU has on the one hand enforced a reduction in national fishing fleets, while on the other hand providing compensatory measures in particularly affected regions and promoting the use of environmentally sound technology. Nevertheless, fishing quotas are considered a major reason why countries such as Norway and Iceland, whose economies are heavily dependent on fishing, have not joined the EU.

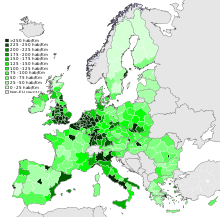

Regional Policy

→ Main article: Regional policy of the European Union

Within the EU, there are a number of regions whose economic performance is far below the EU average, mostly as a result of disadvantageous economic geographic location factors. A classic example of this is the Mezzogiorno in Italy. Such regions - which have grown strongly since 2004 due to the accession of Central and Eastern European countries - are granted special support, whereby differences in the level of development of the areas are to be equalized and regional disparities are to be reduced (Art. 174 et seq. TFEU). To this end, three so-called structural funds have been set up to ensure that the poorer regions catch up economically. The use of these funds is roughly planned in the EU's seven-year financial perspective (currently for the period 2007-2013).

The first of the three structural funds is the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). Among other things, it supports medium-sized companies so that permanent jobs are created. In order to be able to provide more targeted assistance, the funding is usually allocated to individual economic sectors. In addition, infrastructure projects are initiated and technical assistance measures are applied.

The ERDF can operate within the framework of three objectives: The first objective, convergence, applies to regions whose gross domestic product per inhabitant is below 75% of the EU average. The main aim is to modernize the economic structure and create jobs. The second objective, regional competitiveness and employment, concerns the regions that are not eligible under the Convergence objective; the funds earmarked for this are correspondingly lower than those for Objective 1. The priorities of the regional competitiveness and employment objective are to strengthen research, development and finance, as well as environmental protection and risk prevention. To prevent a shock in the loss of subsidies due to a region's transition from Objective 1 to Objective 2, there are two bridging mechanisms: regions that were previously eligible under Objective 1, but whose GDP has increased so that it is now above 75% of the EU average for pre-2004 member states, receive decreasing transitional aid called phasing-in. Other regions that fell into the Objective 1 category until the EU enlargements since 2004, but now no longer fall below the 75% criterion due to the accession of poorer countries for statistical reasons, are awarded decreasing transitional aid called phasing-out. Finally, the third ERDF objective, European territorial cooperation, focuses on transnational cooperation and economic and social development in border regions.

The second fund is the European Social Fund, which, like the ERDF, is applied in all member states. It aims to improve education systems and access to the labor market.

Finally, the Cohesion Fund, established in 1993, is designed to reduce economic and social disparities among member states. Eligible for support under this fund are projects relating to environmental and transport infrastructure in EU member states whose per capita gross domestic product is below 90% of the EU average. Since May 1, 2004, these have been Greece, Portugal, Spain, the Republic of Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia.

For regional development in the member states, the EU plans to spend around 360 billion euros in funding between 2007 and 2013. Often, EU grants are not disbursed directly from Brussels, but indirectly through national and regional authorities in the member states. Directly, the European Commission pays money to governmental or private organizations, such as universities, companies, interest groups and non-governmental organizations.

In addition to projects within the EU, the EU also supports projects in countries that wish to join the EU. These external grants serve, among other things, to support neighborly relations and stabilize the recipient countries.

Foreign and security policy

Common foreign policy

→ Main article: Common foreign and security policy

The aim of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP, Art. 21 et seq. TEU and Art. 205 et seq. TFEU) is to safeguard the common values and interests of the Union, to strengthen security and peace, to promote international cooperation and to strengthen democracy, the rule of law and human rights. Unlike most other EU policies, the CFSP is largely intergovernmental: The governments of the member states unanimously define common strategies, in the formulation of which the European Parliament in particular has almost no say. European foreign policy complements the foreign policy of the nation states, but does not replace it.

However, most of the practical negotiation and coordination work in the CFSP is in the hands of the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. He is also Vice-President of the European Commission and (non-voting) Chairman of the Foreign Affairs Council. He is responsible for some 130 delegations of the European Union to international organizations and third countries. The Lisbon Treaty also provides for the establishment of a European External Action Service, which is to be composed of these delegations as well as of staff from the Council Secretariat and the national diplomatic services and which is also to be fully subordinate to the High Representative (Art. 27 para. 3 TEU). It thus has operational independence and can also set its own priorities within the framework of the Council's guidelines.

While the CFSP has repeatedly been successful in day-to-day diplomacy and joint action by the EU states is now the rule, for example, in votes at the United Nations General Assembly, national governments still frequently pursue their own strategies in international crises. This led, for example, to a fierce diplomatic conflict between EU member states before the 2003 Iraq war (see Iraq Crisis 2003).

The EU's international relations are often governed by bilateral and multilateral agreements that are geared to the economic, but also political interests of both partners. In addition to agreements with the Organization of African, Caribbean and Pacific States (see Development Policy), there are also agreements with other regional free trade organizations, for example with the Southeast Asian ASEAN states, the South American Mercosur, the North American NAFTA, etc. A special relationship exists between the EU and the U.S. as the world's two largest economic blocs and most important Western democratic powers. The EU has also had a special Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) with Russia since 1994. However, the further development of Russian-European relations is controversial among EU member states.

Security and defense policy

Finally, the Common Security and Defense Policy (CSDP, Art. 42 ff. TEU) plays a special role as part of the CFSP. After the failure of the European Defense Community in 1954, military cooperation among Western European states initially took place primarily within the framework of NATO. It was not until the 1990s that the EU began to develop independent security policy structures. To this end, it initially relied on the Western European Union and eventually developed the CSDP. This is intended both to respect the neutrality of certain member states and to be compatible with the NATO affiliation of other member states. The EU has the character of a defensive alliance; that is, in the event of an armed attack on one of the member states, the others must provide it with support (Article 42 (7) TEU).

· Products of joint EU armaments cooperation

·

Eurofighter Typhoon

·

Airbus A400M

·

Eurocopter Tiger