European Parliament

The European Parliament (unofficially also European Parliament or EU Parliament; short EP; lat. Parlamentum Europaeum) with official seat in Strasbourg is the parliament of the European Union (Art. 14 EU Treaty). Since 1979, it has been elected every five years (most recently in 2019) by the citizens of the EU in general, direct, free, secret, but not equal European elections. This makes the European Parliament the only directly elected body of the European Union and the only directly elected supranational institution in the world.

Since the establishment of the Parliament in 1952, its powers in EU law-making have been significantly extended several times, most notably by the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 and most recently by the Lisbon Treaty in 2007, which entered into force on 1 December 2009. Parliament's rights have also been gradually extended with regard to the formation of the executive, i.e. the election of the European Commission. Thus, candidates for the EU Commission must first undergo a hearing in the European Parliament and prove their suitability and ability for the proposed office. This hearing is usually conducted by the relevant committee of the European Parliament and all hearings are also made public via web-stream on the European Parliament's website. Only after successfully passing the hearing can the candidate be elected as a member of the EU Commission, again by the European Parliament (plenary).

The European Parliament lacks the typical opposition between government and opposition factions. Unlike in most national parliaments, where the government groups are usually loyal to the government and support its bills in principle, changing majorities form in the European Parliament depending on the voting topic. This also means that individual MEPs are more independent and have greater influence on EU legislation through their negotiating skills and expertise than is possible for members of national parliaments. In its judgment on the Lisbon Treaty of 30 June 2009, the Federal Constitutional Court grants the European Parliament only limited democratic legitimacy and sees its decision-making powers with regard to further steps towards European integration as limited as a result.

Since the 2014 European elections, the Parliament has comprised a maximum of 750 seats plus the President, i.e. 751 MEPs (Article 14(2) of the EU Treaty). The Parliament currently has seven political groups and 38 non-attached Members. In their home countries, these MEPs are members of around 200 different national parties, most of which have joined together at European level to form European parties.

President of the European Parliament since 3 July 2019 is David Sassoli (S&D). In addition to Strasbourg, the European Parliament's places of work are Brussels and Luxembourg. The Rules of Procedure of the European Parliament contain regulations on the organisation and functioning of the European Parliament.

With the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union on 31 January 2020 (the so-called "Brexit"), the number of mandates allocated per member state changed. Of the 73 UK parliamentary seats, 27 vacant seats were redistributed among EU countries in proportion to their population. 46 seats were put in reserve for a possible EU enlargement.

Tasks

The tasks of the European Parliament are described in Article 14 of the EU Treaty. According to this, the Parliament shall act jointly with the Council as legislator, exercise budgetary powers jointly with the Council and exercise political control. Furthermore, it is to act in an advisory capacity and elect the President of the Commission.

Legislative function

The Parliament shares the legislative function with the Council of the European Union, i.e. it adopts European laws (directives, regulations, decisions). Since the Treaty of Lisbon, the so-called ordinary legislative procedure has applied in most policy areas (Art. 294 TFEU), in which the Parliament and the Council of the EU have equal rights and can each introduce amendments to a legislative text proposed by the European Commission in two readings. In the event of disagreement, the Council and Parliament must reach agreement in a Conciliation Committee in the third reading. However, partly in order to avoid the time-consuming nature of this procedure, more and more legislative proposals are being negotiated in informal trilogue procedures so that they can then be adopted at first reading: between 2004 and 2009, for example, this was the case for 72% of all draft laws, compared with 33% between 1999 and 2004.

Overall, the legislative procedure is similar to the German legislative procedure between the Bundestag and the Bundesrat. However, unlike the Bundestag, the European Parliament has no right of initiative of its own and therefore cannot introduce bills of its own. Only the EU Commission has this right of initiative at EU level, which can, however, be called upon to exercise it by the European Parliament in accordance with Art. 225 TFEU.

In a binding declaration from 2010, the parliamentarians agreed with the Commission to provide an interpretation aid to the applicable European law provisions, so that in future, at the instigation of the Parliament, the Commission must present a draft law within twelve months or give detailed reasons why it is not doing so within three months. Thus, for the first time, the European Parliament has at least a limited right of initiative.

In addition to the ordinary legislative procedure, there are other forms of lawmaking in the EU in which Parliament has less say. Under the Treaty of Nice, however, these now only extend to a few specific policy areas. In the area of competition policy, for example, Parliament only has to be consulted. In the Common Foreign and Security Policy, too, it has hardly any say at all, in accordance with Article 36 TEU. The High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy must keep Parliament regularly informed and ensure that Parliament's views are "duly taken into account". Since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty on 1 December 2009, the European Parliament has the right to propose amendments to draft legislation in the area of the Common Commercial Policy, as well as to reject the respective legislative act.

After this integration into the ordinary legislative procedure, negotiation results of the European Commission in the area of the Common Commercial Policy require the approval of the European Parliament before proceeding to decision-making by the European Council.

Budgeting function

The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union (Council of Ministers) decide jointly on the budget of the European Union (€141.5 billion in 2010). The European Commission proposes a draft budget; in the budgetary procedure, Parliament and the Council of Ministers can then decide on amendments. If both agree, the budget with the amendments enters into force. If there are differences between the Parliament and the Council on the plan, a complex procedure of mutual consultations and votes is carried out. If there is still no agreement after this political fine-tuning, the Conciliation Committee is called in as a last resort. In political practice, this usually then leads to a compromise and agreement. The details of the procedure are set out in Article 314 of the TFEU.

Control function

Parliament also exercises parliamentary control over the European Commission and the Council of the European Union. To this end, it can set up committees of inquiry and, if necessary, bring actions before the European Court of Justice. This also applies in areas such as the common foreign and security policy, where the Commission and the Council have executive functions and Parliament's legislative rights of co-determination are limited. In order for Parliament to fulfil this scrutiny role, the other EU institutions, notably the Commission, the Council and the European Central Bank, must report regularly to Parliament on their activities; the President of Parliament also attends European Council summits. In addition, MEPs can put written and oral parliamentary questions to the Commission and the Council. While the right to put questions to the Commission has an explicit basis in primary law in Article 230 TFEU, the right to put questions to the Council is based on a voluntary declaration by the Council in 1973 to answer questions from Parliament.

Another effective means of parliamentary control is the vote of no confidence pursuant to Art. 234 TFEU. With a double majority - two thirds of the votes cast and a majority of the members - Parliament can pass a vote of no confidence in the Commission. The entire Commission must then resign as a whole.

Dial function

The Parliament also plays an important role in the appointment of the Commission: According to Article 17 of the EU Treaty, the Parliament elects the President of the European Commission. However, the right of nomination lies with the European Council, which must, however, "take into account" the result of the previous European elections. So far, this provision has only been interpreted in such a way that the proposed candidate comes from the European party that achieved the best result in the European elections; the main negotiations prior to the nomination of the Commission President took place between the governments of the Member States. However, there have been repeated proposals that the European parties should nominate top candidates for the office of Commission President during the election campaign, in order to strengthen the role of the Parliament vis-à-vis the European Council. However, attempts to do so before the 2009 European elections failed due to disagreements within the European parties. In the 2014 European election, the five major European party families (Conservatives, Social Democrats, Liberals, Greens, Socialists) nominated Europe-wide leading candidates for the first time, who were more or less in the foreground during the election campaign.

In addition to the Commission President, the Parliament also confirms the entire Commission. Here too, the candidates are nominated by the European Council, although the decision is traditionally left largely to the national governments. However, the Parliament examines the competence and integrity of the individual Commissioners in the respective specialist committees and then decides in plenary on the appointment of the Commission. It can only approve or reject the Commission as a whole, not individual members. It has happened on several occasions that the Parliament has enforced the withdrawal of individual candidates deemed unsuitable by threatening to reject the Commission as a whole, such as Rocco Buttiglione in 2004 and Rumjana Schelewa in 2009.

In addition, the Parliament can force the resignation of the Commission through a vote of no confidence (Art. 234 TFEU). To do so, it requires a two-thirds majority, which is quite a high hurdle compared to national parliaments and gives the Commission a relatively large degree of autonomy. The right to a vote of no confidence is one of the oldest powers of the Parliament. It has never been used before; in 1999, the Santer Commission resigned in unison after Parliament threatened a vote of no confidence.

In the appointment of other EU officials outside the European Commission, on the other hand, the Parliament usually has only a smaller say. When appointing the members of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank (ECB), it must be consulted by the Council of the European Union in accordance with Art. 283 TFEU, but cannot block its decision. In other respects, too, the European Parliament has little formal control over the ECB, which, according to the EU Treaty, is supposed to be independent in its decisions. The same applies to the judges at the Court of Justice of the European Union, in whose election the European Parliament is not involved at all pursuant to Art. 253f. TFEU Treaty, the European Parliament is not involved at all.

Every European citizen has the right to petition the European Parliament, which is heard by the Committee on Petitions. Parliament also appoints the European Ombudsman, who investigates citizens' complaints about maladministration by the EU institutions.

| ||

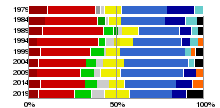

| Before 1979 (1952-1979) | ||

| 1st legislative period (1979-1984) | ||

| 2nd parliamentary term (1984-1989) | ||

| 3rd parliamentary term (1989-1994) | ||

| 4th parliamentary term (1994-1999) | ||

| 5th parliamentary term (1999-2004) | ||

| 6th parliamentary term (2004-2009) | ||

| 7th legislative period (2009-2014) | ||

| 8th legislative period (2014-2019) | ||

| 9th parliamentary term (2019-2024) |

Fractions

→ Main article: Political group in the European Parliament

The European Parliament - like a national parliament - is not organised along national groups, but according to ideological groups. These are composed of MEPs with similar political views and essentially correspond to European political parties. However, different European parties often form a common group (for example, the Greens/EFA group, composed of the European Green Party and the European Free Alliance, or the ALDE group, formed by the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe together with the European Democratic Party), and several groups also include non-party MEPs. Since the 2009 European elections, at least 25 MEPs from at least a quarter of the Member States (i.e. seven) are required to form a political group.

Below the parliamentary group level, the Members of Parliament also organise themselves into so-called national delegations, each of which comprises the members of a national party. They thus correspond roughly to the regional groups in the German Bundestag.

Since the European Parliament - unlike national parliaments - does not elect a government in the traditional sense, the juxtaposition of governing coalition and opposition factions is less pronounced here. Instead of confrontation, compromise solutions are usually sought between the major parties. Traditionally, the two largest groups, the conservative Christian Democratic EPP and the social democratic S&D, dominate the scene. Until 1999, the Social Democrats made up the largest group, since then the EPP. No single group has ever had an absolute majority in the European Parliament, but this informal "grand coalition" has always had a majority of between 50% and 70%.

This constellation is further promoted by the fact that, according to the ordinary legislative procedure, an absolute majority of the elected (not the present) members of the European Parliament is necessary for the adoption of a decision in second reading. Since not all MEPs are usually present for plenary sessions, the Parliament can in fact only organise the necessary majorities through cooperation between the EPP and the S&D. A clear sign of the cooperation between the large political groups is also their agreement to share the five-year mandate of the President of the Parliament among themselves. Nevertheless, the grand coalition is still not formalised, there is neither a coalition agreement nor a fixed joint "government programme". In the day-to-day work of the European Parliament, decisions are usually taken with changing majorities from different groups, albeit almost always starting from a compromise between EPP and S&D.

However, the practice of the Grand Coalition was repeatedly criticised by members of the smaller groups, in particular the Liberals and the Greens. During the 1999-2004 legislative period, the corruption scandal surrounding the Santer Commission led to a temporary break in the Grand Coalition and cooperation between the EPP and the Liberals. In 2004 - during the discussion on the appointment of Rocco Buttiglione as Justice Commissioner - the EPP and the Liberals distanced themselves from each other again, so that - despite the differences between the EPP and the Social Democrats - a new informal Grand Coalition was finally formed. Before the 2009 European elections, Graham Watson, the Liberal Group leader, announced his aim to be part of a stable coalition with the EPP or Social Democrats in the next parliamentary term. However, no such "small" coalition achieved a majority in the elections. The following table lists the distribution of MEPs among the political groups (absolute numbers and percentages) since 1979, at the beginning and end of each legislative term.

| Legislative period | Communists/Left | Socialists/ | Green | Regional. | Liberal | Christian Democrats/Conservatives | Conservative | National Conservative / Eurosceptic | Right-wing extremists | Unaffiliated | Total | |||

| 1979–1984 | COM | SCO | CDI | L | EVP | ED | DFA | NI | Total | |||||

| 44 (10,7 %) | 113 (27,6 %) | 11 (2,7 %) | 40 (9,8 %) | 107 (26,1 %) | 64 (15,6 %) | 22 (5,4 %) | 09 (2,2 %) | 410 | ||||||

| 48 (11,1 %) | 124 (28,6 %) | 12 (2,8 %) | 38 (8,8 %) | 117 (27,0 %) | 63 (14,5 %) | 22 (5,1 %) | 10 (2,3 %) | 434 | ||||||

| 1984–1989 | COM | SCO | RBW | L | EVP | ED | RDE | ER | NI1 | Total | ||||

| 41 (9,4 %) | 130 (30,0 %) | 20 (4,6 %) | 31 (7,1 %) | 110 (25,3 %) | 50 (11,5 %) | 29 (6,7 %) | 16 (3,7 %) | 07 (1,6 %) | 434 | |||||

| 48 (9,3 %) | 166 (32,0 %) | 20 (3,9 %) | LDR45 | 113 (21,8 %) | 66 (12,7 %) | 30 (5,8 %) | 16 (3,1 %) | 14 (2,7 %) | 518 | |||||

| 1989–1994 | GUE | CG | SCO | V | ARC | LDR | EVP | ED | RDE | DR | NI | Total | ||

| 28 (5,4 %) | 14 (2,7 %) | 180 (34,7 %) | 30 (5,8 %) | 13 (2,5 %) | 49 (9,5 %) | 121 (23,4 %) | 34 (6,6 %) | 20 (3,9 %) | 17 (3,3 %) | 12 (2,3 %) | 518 | |||

| 13 (2,5 %) | SPE198 | 27 (5,2 %) | 14 (2,7 %) | 45 (8,7 %) | 162 (31,3 %) | 20 (3,9 %) | 12 (2,3 %) | 27 (5,2 %) | 518 | |||||

| 1994–1999 | GUE | SPE | G | ERA | ELDR | EPP/ED | RDE | FE | EN | NI | Total | |||

| 28 (4,9 %) | 198 (34,9 %) | 23 (4,1 %) | 19 (3,4 %) | 44 (7,8 %) | 156 (27,5 %) | 26 (4,6 %) | 27 (4,8 %) | 19 (3,4 %) | 27 (4,8 %) | 567 | ||||

| GUE/NGL34 | 214 (34,2 %) | 27 (4,3 %) | 21 (3,4 %) | 42 (6,7 %) | 201 (32,1 %) | UFE34 | I-EN15 | 38 (6,1 %) | 626 | |||||

| 1999–2004 | GUE/NGL | SPE | Greens/EFA | ELDR | EPP/ED | UEN | EDD | TDI | NI | Total | ||||

| 42 (6,7 %) | 180 (28,8 %) | 48 (7,7 %) | 50 (8,0 %) | 233 (37,2 %) | 30 (4,8 %) | 16 (2,6 %) | 18 (2,9 %) | 09 (1,4 %) | 626 | |||||

| 55 (7,0 %) | 232 (29,4 %) | 47 (6,0 %) | 67 (8,5 %) | 295 (37,4 %) | 30 (3,8 %) | 18 (2,3 %) | 44 (5,6 %) | 788 | ||||||

| 2004–2009 | GUE/NGL | SPE | Greens/EFA | ALDE | EPP/ED | UEN | IND/DEM | ITS2 | NI | Total | ||||

| 41 (5,6 %) | 200 (27,3 %) | 42 (5,8 %) | 088 (12,0 %) | 268 (36,7 %) | 27 (3,7 %) | 37 (5,1 %) | 29 (4,0 %) | 732 | ||||||

| 41 (5,2 %) | 217 (27,6 %) | 43 (5,5 %) | 100 (12,7 %) | 288 (36,7 %) | 44 (5,6 %) | 22 (2,8 %) | 30 (3,8 %) | 785 | ||||||

| 2009–2014 | GUE/NGL | S&D | Greens/EFA | ALDE | EVP | ECR | EFD | NI | Total | |||||

| 35 (4,8 %) | 184 (25,0 %) | 55 (7,5 %) | 84 (11,4 %) | 265 (36,0 %) | 55 (7,5 %) | 32 (4,4 %) | 27 (3,7 %) | 736 | ||||||

| 35 (4,6 %) | 195 (25,5 %) | 58 (7,3 %) | 83 (10,8 %) | 274 (35,8 %) | 57 (7,4 %) | 31 (4,0 %) | 33 (4,3 %) | 766 | ||||||

| 2014–2019 | GUE/NGL | S&D | Greens/EFA | ALDE | EVP | ECR | EFDD3 | ENF | NI | Total | ||||

| 52 (6,9 %) | 191 (25,4 %) | 50 (6,7 %) | 67 (8,9 %) | 221 (29,4 %) | 70 (09,3 %) | 48 (6,4 %) | 52 (6,9 %) | 751 | ||||||

| 52 (6,9 %) | 187 (24,9 %) | 52 (6,9 %) | 69 (9,2 %) | 216 (28,8 %) | 77 (10,3 %) | 42 (5,6 %) | 36 (4,8 %) | 20 (2,7 %) | 751 | |||||

| since 2019 | GUE/NGL | S&D | Greens/EFA | RE | EVP | ECR | ID | NI | Total | |||||

| 41 (5,5 %) | 154 (20,5 %) | 75 (10,0 %) | 108 (14,4 %) | 182 (24,2 %) | 62 (8,3 %) | 73 0(9,7 %) | 56 (7,5 %) | 751 | ||||||

| The Left39 | 146 (20,6 %) | 73 (10,4 %) | 98 (13,8 %) | 177 (24,8 %) | 63 (8,9 %) | 71 (10,5 %) | 38 (5,5 %) | 705 | ||||||

1 In addition, from 17 September 1987 to 17 November 1987, the Group for the Technical Coordination and Defence of Independent Groups and Members had 12 members.

2 The Identity, Tradition, Sovereignty Group existed between January 2007 and November 2007 and comprised 20 to 23 members.

3 The Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group was dissolved on 16 October 2014 and re-established on 20 October.

Current composition of Parliament

The following table shows the composition of the European Parliament by national parties (as of 23 June 2021). For an overview of the parliamentarians in detail, see List of Members of the 9th European Parliament.

| Fraction Country | The Left | S&D | Greens/EFA | Renew | EVP | EKR | ID | f'loose | seats in parliament | ||||||||

| European Union | 39 | 146 | 73 | 98 | 177 | 63 | 71 | 38 | 705 | ||||||||

| Belgium | PTB-PVDA | 1 | PSVooruit |

| EcoloGroen |

| Open VLDMR |

| CD&VcdHCSP |

| N-VA | 3 | VB | 3 | 21 | ||

| Bulgaria | BSP | 5 | DPS | 3 | GERBSDSDB/DSB | 511 | IMRO | 2 | 17 | ||||||||

| Denmark Denmark | EL | 1 | S | 3 | SF | 2 |

|

| KF | 1 | DF | 1 | 14 | ||||

| Germany | Left | 5 | SPD | 16 | GreensÖDP | 211111 | FDPFW |

| CDU | 2361 | Mountain | 1 | AfD | 10 | PARTY |

| 96 |

| Estonia | SDE | 2 | REK |

| I | 1 | EKRE | 1 | 7 | ||||||||

| Finland | VAS | 1 | SDP | 2 | VIHR | 3 | KESKRKP |

| KOK | 3 | PS | 2 | 14 | ||||

| France | FiGRS |

| PSPPND |

| EELVAEIRPS/PNC |

| LREMMoDemMRSLAgirItalia |

| LRLC |

| RN |

| 79 | ||||

| Greece | Syriza | 6 | Kinal | 2 | ND | 8 | EL | 1 | KKEELASYN |

| 21 | ||||||

| Ireland | I4CSFFlanagan |

| Green | 2 | FF | 2 | FG | 5 | 13 | ||||||||

| Italy | PD | 18 | Independent | 4 | Italia Viva |

| FISVPSud | 711 | FdI | 8 | Lega | 25 | M5S |

| 76 | ||

| Croatia | SDP | 4 | IDS | 1 | HDZ | 4 | HKS | 1 | Živi zid |

| 12 | ||||||

| Latvia | SDPS | 2 | LKS | 1 | AP! | 1 | JV | 2 | NA | 2 | 8 | ||||||

| Lithuania | LSDP | 2 | LVZS | 2 | LRLS | 1 | TS-LKDAMT |

| LLRA | 1 | DP | 1 | 11 | ||||

| Luxembourg | LSAP | 1 | Gréng | 1 | DP | 2 | CSV | 2 | 6 | ||||||||

| Malta | PL | 4 | PN | 2 | 6 | ||||||||||||

| Netherlands | PvdD | 1 | PvdA | 6 | GL | 3 | VVD |

| CDA |

| JA21 |

| PVV | 1 | GO | 1 | 29 |

| Austria | SPÖ | 5 | Green | 3 | NEOS | 1 | ÖVP | 7 | FPÖ | 3 | 19 | ||||||

| Poland | SLDWiosna |

| Spurek | 1 |

| 1232 | PiSSPPJG | 2421 | 52 | ||||||||

| Portugal | BECDU/PCP |

| PS | 9 | Guerreiro | 1 | PSDCDS-PP |

| 21 | ||||||||

| Romania | PSDPROPPU | 811 | USRPLUS |

| PNLUDMRPMP | 1022 | PNȚ-CD | 1 | 33 | ||||||||

| Sweden | V | 1 | S | 5 | MP | 3 |

|

| M |

| SD | 3 | 21 | ||||

| Slovakia | SmerSD | 3 | PS |

| SPOLUKDHOĽaNO |

| SaS | 1 | SPHR |

| 14 | ||||||

| Slovenia | SD | 2 | LMŠ | 2 | SDSSLSNSi |

| 8 | ||||||||||

| Spain | UP/PodemosUP/R. PalopUP/IUAnticapitalistasAR/EH |

| PSOE | 21 | AR/ERCUP/CatComú |

| CsEAJ-PNV |

1 | PP | 13 | Vox | 4 | Junts | 3 | 59 | ||

| Czech Republic | KSČM | 1 | Maxová | 1 | Piráti | 3 | ANO | 5 | TOP 09 |

| ODS | 4 | SPD | 2 | 21 | ||

| Hungary | DKMSZP |

| Momentum | 2 | KDNP | 1 | FideszJobbik |

| 21 | ||||||||

| Cyprus Republic of | AKEL | 2 | DIKOEDEK |

| DISY | 2 | 6 | ||||||||||

| European Union | 39 | 146 | 73 | 98 | 177 | 63 | 71 | 38 | 705 | ||||||||

| GUE/NGL | S&D | Greens/EFA | Renew | EVP | EKR | ID | f'loose | seats in parliament | |||||||||

Bureau and Conference of Presidents

→ Main article: President of the European Parliament

The Bureau of the European Parliament is elected by an absolute majority of MEPs from among their number. It consists of the President of Parliament, 14 Vice-Presidents and five Quaestors.

The President of Parliament represents Parliament externally and chairs plenary sittings, although he or she may also be represented by the Vice-Presidents. The Bureau is also responsible for the administration of Parliament and its budget. The Quaestors, who have only a consultative vote in the Bureau, are mainly responsible for administrative activities that directly concern the Members.

The members of the Presidency are each elected for half a legislative term, i.e. for two and a half years. Until 1989, the election of the President of Parliament was a relatively hotly contested post, sometimes requiring third and fourth ballots. It was not until 1989 that an agreement was reached between the EPP and the PES on a division of this post, which was then shared between the two large groups until 1999 and again since 2004, so that the Parliament is led by a Social Democrat for half of each legislative term and by an EPP member for the other half. Only in the period 1999-2004 was there a similar agreement between the EPP and the liberal ALDE group instead. In the first half of the 2009-2014 parliamentary term, the Pole Jerzy Buzek (EPP) was parliamentary president; in January 2012, the German Martin Schulz, who had been group leader of the Social Democrats since 2004, took over. The 14 Vice-Presidents were from the EPP (5), S&D (5), ALDE (2) and Greens/EFA (1) groups, one Vice-President was non-attached. The five Quaestors were members of the EPP (2), S&D, ALDE and GUE-NGL (1 each).

Another important body for the organisation of the European Parliament is the Conference of Presidents, which is made up of the President of Parliament and the chairmen of all the political groups. The Conference of Presidents decides, among other things, on the agenda of the plenary sessions and on the composition of the parliamentary committees.

Presidents of the European Parliament since its foundation

| President | Tenure | Country of origin | national party | European party/political direction | Fraction |

| David Sassoli | since 2019 | Italy | PD | SPE | S&D |

| Antonio Tajani | 2017–2019 | Italy | FI | EVP | EVP |

| Martin Schulz | 2012–2017 | Germany | SPD | SPE | S&D |

| Jerzy Buzek | 2009–2012 | Poland | PO | EVP | EVP |

| Hans-Gert Pöttering | 2007–2009 | Germany | CDU | EVP | EPP/ED |

| Josep Borrell | 2004–2007 | Spain | PSOE | SPE | S&D |

| Pat Cox | 2002–2004 | Ireland | nonpartisan | liberal | ELDR |

| Nicole Fontaine | 1999–2002 | France | UDF | liberal-conservative | EPP/ED |

| José María Gil-Robles | 1997–1999 | Spain | PP | EVP | EVP |

| Klaus Hänsch | 1994–1997 | Germany | SPD | SPE | S&D |

| Egon Klepsch | 1992–1994 | Germany | CDU | EVP | EVP |

| Enrique Barón Crespo | 1989–1992 | Spain | PSOE | Confederation of Social Democratic Parties | S&D |

| Charles Henry Plumb | 1987–1989 | United Kingdom | Conservatives | conservative | ED |

| Pierre Pflimlin | 1984–1987 | France | CDS | christiandemocrat | EVP |

| Piet Dankert | 1982–1984 | Netherlands | PvdA | Confederation of Social Democratic Parties | S&D |

| Simone Veil | 1979–1982 | France | UDF | liberal | Liberal |

| Emilio Colombo | 1977–1979 | Italy | DC | EVP | EVP |

| Georges Spénale | 1975–1977 | France | PS | social democratic | S&D |

| Cornelis Berkhouwer | 1973–1975 | Netherlands | VVD | liberal | Liberal |

| Walter Behrendt | 1971–1973 | Germany | SPD | social democratic | S&D |

| Mario Scelba | 1969–1971 | Italy | DC | christiandemocrat | Christian Democrats |

| Alain Poher | 1966–1969 | France | MRP | christiandemocrat | Christian Democrats |

| Victor Leemans | 1965–1966 | Belgium | PSC-CVP | christiandemocrat | Christian Democrats |

| Jean Duvieusart | 1964–1965 | Belgium | PSC-CVP | christiandemocrat | Christian Democrats |

| Gaetano Martino | 1962–1964 | Italy | PLI | liberal | Liberal |

| Hans Furler | 1960–1962 | Germany | CDU | christiandemocrat | Christian Democrats |

| Robert Schuman | 1958–1960 | France | MRP | christiandemocrat | Christian Democrats |

| Hans Furler | 1956–1958 | Germany | CDU | christiandemocrat | Christian Democrats |

| Giuseppe Pella | 1954–1956 | Italy | DC | christiandemocrat | Christian Democrats |

| Alcide De Gasperi | 1954 | Italy | DC | christiandemocrat | Christian Democrats |

| Paul-Henri Spaak | 1952–1954 | Belgium | BSP | social democratic | S&D |

Committees

→ Main article: Committees of the European Parliament

As is customary in parliaments, MEPs specialise in order to be able to deal with issues in an expert manner. They are appointed by the political groups or the non-attached group to a total of 20 standing committees and three subcommittees, which are responsible for specific subject areas and prepare the work of the plenary sessions. Parliament also has the option of setting up temporary committees and committees of inquiry. The chairmen of all the committees together form the Conference of Committee Chairs, which can make proposals to the Conference of Presidents (i.e. the political group chairmen) on the work of the committees and the drawing up of the agenda.

The official abbreviations of the committees included in the following list are generally based on the English or French names.

| Designation | Abbreviation | |||

| Foreign Affairs | AFET |

| ||

| Human rights (AFET subcommittee) | DROI |

| ||

| Security and Defence (AFET subcommittee) | SEDE |

| ||

| Employment and social affairs | EMPL |

| ||

| Internal market and consumer protection | IMCO |

| ||

| Civil liberties, justice and home affairs | LIBE |

| ||

| Development | DEVE |

| ||

| Fishing | PECH |

| ||

| Budget | BUDG |

| ||

| Budgetary control | CONT |

| ||

| Industry, research and energy | ITRE |

| ||

| International trade | INTA |

| ||

| Constitutional questions | AFCO |

| ||

| Culture and education | CULT |

| ||

| Agriculture and rural development | AGRI |

| ||

| Petitions | PETI |

| ||

| Law | JURI |

| ||

| Women's rights and gender equality | FEMM |

| ||

| Regional development | REGI |

| ||

| Environmental issues, public health and food safety | ENVI |

| ||

| Transport and tourism | TRAN |

| ||

| Economy and currency | ECON |

| ||

| Tax issues (ECON subcommittee) | FISC |

|

Interparliamentary delegations

Delegations have been set up in the European Parliament to maintain relations with parliaments of third countries and to promote the exchange of information with them. Interparliamentary delegations are set up on a proposal from the Conference of Presidents. The interparliamentary meetings take place once a year in one of the European Parliament's places of work and in the third country concerned.

These delegations play a special role in the accession process of a candidate country to the European Union. This is monitored by a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) composed of a delegation from the European Parliament and a delegation from the candidate or associated country. At the meetings, the members of the delegations inform each other about their priorities and the implementation of the association agreements.

The EURO-NEST Parliamentary Assembly looks after the relations of the Eastern European countries with which the EU is linked through the Eastern Partnership. In the framework of the Union for the Mediterranean, a delegation of the European Parliament also participates in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Union for the Mediterranean (PA-UfM).

A European Parliament delegation also participates in the NATO Parliamentary Assembly.

Informal groupings

In addition to these institutionalised forms of work, there are also informal cross-group groupings of MEPs. These are, on the one hand, the so-called intergroup working groups, which are intended to promote exchange on certain special topics and contact with civil society. In the 2009-2014 parliamentary term, these range from the topic of "water" to "Tibet" or "reindustrialisation" to the "Way of St James". The intergroups receive certain support, such as logistical support, from Parliament and must therefore meet certain minimum requirements, which are laid down in an internal regulation. However, unlike the committees, they are not bodies of Parliament.

In addition, there are also cross-group associations of MEPs that are completely independent of the parliamentary infrastructure and represent certain common positions. These include, for example, the Spinelli Group, which advocates European federalism and comprises around 100 MEPs from various political groups.

Parliament's administration and Members' assistants

Members of the European Parliament are assisted in their work by Parliament's Administration: The General Secretariat is divided into ten Directorates-General (not to be confused with the Directorates-General of the European Commission) and the Legal Service. It is headed by a Secretary General, since March 2009 this is the German Klaus Welle.

The Directorates-General closer to policy are located with their staff in Brussels, the others in Luxembourg. With about 3500 employees, slightly more than two thirds of the total of about 5000 employees work here, including many translators and administrative services remote from the sessions. The Speaker of the European Parliament is the Spaniard Jaume Duch Guillot.

In addition to administrative support, Members have the possibility of employing personal assistants, known in the European Parliament as parliamentary assistants, from their monthly secretarial allowance.

In total, there are around 1400 assistants accredited to Parliament.

Parliamentary groups in the election periods since 1979, in each case at constitution. From left to right: Communists and Socialists, The Left Social Democrats, S&D Greens/Regionalists (1984-1994 "Rainbow"), Greens/EFA Greens (excluding regionalists, 1989-1994) "technical" group (1979-1984, 1999-2001) Unaffiliated Liberals, Renew Radical Alliance (1994-1999) Christian Democrats, EPP Forza Europe (1994-1995) Conservatives (1979-1992), ECR Eurosceptic (1994-2014) Gaullists, National Conservatives (1979-2009) Far Right (1984-1994, as of 2019), id.

Anna Lindh Room in Brussels shortly after the end of a meeting of the Foreign Affairs Committee, which is meeting here.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the European Parliament?

A: The European Parliament is the parliament of the European Union (EU).

Q: What was the European Parliament formerly known as?

A: The European Parliament was formerly known as the European Parliamentary Assembly or Common Assembly.

Q: Who elects the members of the European Parliament?

A: EU citizens elect the members of the European Parliament once every five years.

Q: What is the role of the European Parliament in the institutions of the Union?

A: The European Parliament, together with the Council of Ministers, is the law-making branch of the institutions of the Union.

Q: Where does the European Parliament meet?

A: The European Parliament meets in two locations: Strasbourg and Brussels.

Q: How often are members of the European Parliament elected?

A: Members of the European Parliament are elected once every five years by EU citizens.

Q: What body does the European Parliament work together with to create laws?

A: The European Parliament works together with the Council of Ministers to create laws as a law-making branch of the institutions of the Union.

Search within the encyclopedia