Euro

![]()

EUR is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see Euro (disambiguation) and EUR (disambiguation).

The euro (Greek ευρώ, Cyrillic евро; ISO code: EUR, symbol: €) is, according to Article 3(4) TEU, the currency of the European Economic and Monetary Union, a policy area of the European Union (EU) governed by Articles 127-144 TFEU. It is issued by the European Central Bank and acts as the common official currency in 19 EU Member States, which together form the Eurozone, and in six other European countries. After the US dollar, the euro is the world's most important reserve currency.

The euro was introduced as book money on 1 January 1999 and as cash three years later on 1 January 2002. It thus replaced the national currencies as means of payment. Euro coins are minted by the national central banks of the 19 Eurosystem countries and currently by four other countries, each with a country-specific reverse side. In the first printing series, the euro banknotes from different countries differ only in the letter in the first position of the serial number, which indicates on behalf of which national central bank the note was printed. In the second printing series from 2013 onwards, which is intended to provide greater protection against counterfeiting, the serial number begins with two letters, the first of which indicates the printing works.

Since 2020, the European Central Bank, along with many other central banks and the Bank for International Settlements, has been studying whether it makes sense to issue a digital euro, or e-euro, as digital central bank money.

.jpg)

Second series euro banknotes

Euro notes and coins

History of the Euro

The euro as a political project

→ Main article: History of the European Economic and Monetary Union

The idea of a single European currency to facilitate trade between the member states of the European Economic Community (creation of a "common European market") arose quite early in the history of European integration. In 1970, the plan was given concrete form for the first time in the "Werner Plan", according to which a European monetary union was to be realised by 1980. The plan led to the foundation of the European Exchange Rate Association ("currency snake") in 1972. Following the collapse of the Bretton Woods system (March 1973), this could not be implemented as planned. The following years were marked by the consequences of the first oil crisis: in the autumn/winter of 1973/74, the oil price quadrupled; in some European countries, trade unions used this occasion to push through double-digit wage increases (→Kluncker Round). It is disputed whether there was a wage-price spiral or a price-wage spiral (what was cause, what was effect? ). Many European countries had stagflation (i.e. stagnation and inflation); the crisis phase at that time was and is also referred to as Eurosclerosis.

By the end of 1978, several countries had left the exchange rate union. The European Community focused its activities strongly on the agricultural sector (Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)); in many countries a net contributor debate began that lasted for decades. Industrialised countries such as Germany and the United Kingdom became net contributors; agricultural countries such as France, Spain and Portugal were net recipients.

The European Monetary System (EMS) was established in 1979. It was intended to prevent fluctuations in national currencies beyond a certain range. Therefore, the European Currency Unit ECU was created. The ECU was a basket currency, which can be called the precursor of the euro. The ECU served only as a unit of account and did not exist as cash, although some token special coins were minted. Some EC Member States issued government bonds in ecus (they were traded on stock exchanges like other government bonds) and borrowed in ecus.

In 1988, a committee headed by EC Commission President Jacques Delors drew up the so-called "Delors Report". In the course of the reunification sought by Germany, according to newspaper reports, the then French President François Mitterrand linked France's agreement to reunification with the agreement of the then German Chancellor Helmut Kohl to the "deepening of economic and monetary union", i.e. with the introduction of the euro. Kohl disagreed with this account but, as he later wrote in his book Aus Sorge um Europa (Out of Concern for Europe), would have considered the common European currency a reasonable price to pay for German unification. He agreed to the project of introducing the euro without first consulting Bundesbank President Hans Tietmeyer. As proposed in the Delors Report, the European Economic and Monetary Union was created in three steps:

- The first stage of monetary union was launched on 1 July 1990 with the establishment of the free movement of capital between the EC Member States. After the legal foundations for further implementation had been laid in the Maastricht Treaty in 1992,

- the second stage began on 1 January 1994 with the establishment of the European Monetary Institute (EMI, the predecessor of the ECB) and the review of the budgetary situation of the Member States.

- The final stage was reached with the establishment of the European Central Bank (ECB) on 1 June 1998 and the final fixing of the exchange rates of the national currencies to the euro on 1 January 1999. From then on, the exchange rates (also known as currency parities) of the participating countries were irrevocably fixed.

On 2 May 1998, the Heads of State and Government of the European Community decided in Brussels to introduce the euro. Chancellor Kohl was aware that he was acting against the will of a broad majority of the population. In a March 2002 interview that became public in 2013, he commented, "In one case [introducing the euro] I was like a dictator." But he had made the decision because he saw the euro as "a synonym for Europe" and a unique opportunity for Europe to grow together peacefully.

Participating countries

- 1999: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Monaco1 , Netherlands, Portugal, San Marino1 , Spain and Vatican City1

- 2001: Greece

- 2002: Kosovo2 and Montenegro2

- 2007: Slovenia

- 2008: Malta and Cyprus

- 2009: Slovakia

- 2011: Estonia

- 2014: Latvia and Andorra1

- 2015: Lithuania

1 with formal agreements

2 passive euro users

Realisation of the Euro project

EU convergence criteria and the Stability and Growth Pact

→ Main article: EU convergence criteria

In the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, the EU member states agreed on certain "convergence criteria" that states had to meet in order to adopt the euro as their currency. Specifically, they include the stability of public budgets, the price level, exchange rates with the other EU countries and the nominal long-term interest rate. On the initiative of the then German Finance Minister Theo Waigel, the first of these criteria was enshrined at the Dublin summit in 1996, even beyond the entry into the euro. This Stability and Growth Pact allows the euro countries a maximum annual new debt of 3 % and a total debt level of no more than 60 % of their gross domestic product.

However, both before and after the introduction of the euro, Member States repeatedly breached these rules. Greece, in particular, was only able to adopt the euro on the basis of falsified statistics, and many Member States, including Germany and France, repeatedly breached the Stability and Growth Pact. However, the sanctions provided for therein against euro countries with excessive deficits, which can be imposed by the finance ministers of the other Member States, have not yet been applied once. Particularly as a result of the sovereign debt crisis in some European countries, this led to a political debate from 2010 onwards about the European Economic and Monetary Union as a possible fiscal union.

Naming

After the old clearing currency ECU had initially been expected to be used for the planned common currency, criticism was voiced at the beginning of the 1990s that it was too technical and impersonal as an abbreviation for European Currency Unit. The fact that the name could be understood in reference to the French Écu, known since the Middle Ages, was largely overlooked. Helmut Kohl complained that "Écu" resembled the word "cow" in German. On 16 December 1995, the European Council in Madrid therefore decided on a different name for the new currency: "Euro". In accordance with the rules, the term should only be used in the singular (see below, plural forms).

Previously, alternative proposals were also under discussion. Important candidates were the European franc (which in its Spanish translation, however, would have inappropriately reminded Franco of Francisco Franco), the European crown and the European guilder. The use of an already familiar currency name was intended to signal continuity and consolidate public confidence in the new currency. In addition, some participating states could have kept the previous name of their currency. However, this very option also met with criticism, as it would have implied a preference for certain member states over others. In the end, all proposals failed due to the reservations of individual states, especially Great Britain. In response, the German delegation led by then Finance Minister Theodor Waigel proposed the name "euro". In the resolution of the German Bundestag there was still talk of extending the currency name regionally with the names of the previous currencies, i.e. "Euro-Mark" in Germany, "Euro-Franc" in France.

In a video published in 2017 at tagesspiegel.de, Theodor Waigel told how he had invented and imposed the name euro in 1995.

The symbolic denomination euro on a medal can be traced for the first time for an issue from 1965. Another private coinage with this nominal denomination was produced in the Netherlands in 1971. The first letter of the euro denomination is written as a C with a short, slightly curved stroke. The first letter of the inscription EUROPA FILIORUM NOSTRORUM DOMUS (Latin: Europe [is] the house of our children) is written in the same way.

Introduction of the euro as book money

On 31 December 1998 the exchange rates between the euro and the individual currencies of the Member States were irrevocably fixed, and on 1 January 1999 the euro became the legal accounting currency. It replaced the former basket currency ECU (European Currency Unit) at a conversion ratio of 1:1. One day later, on 2 January, European stock exchanges were already quoting all securities in euros.

Another change in connection with the introduction of the euro was the change in the method of price presentation for foreign exchange. In Germany, price quotation (1 USD = x DEM) was the usual form of presentation until the reference date. Since 1 January 1999, the value of foreign exchange in all participating countries has been presented in the form of the indirect quotation (1 EUR = x USD). Furthermore, since 1 January 1999, credit transfers and direct debits could be issued in euro. Accounts and savings books could alternatively be denominated in euro or the old national currency.

The European Council decided in Santa Maria da Feira in June 2000, on a recommendation from the European Commission, to admit Greece to the euro area. Greece joined the euro two years after the other Member States on 1 January 2001.

The final transition to the euro

Germany

Cash exchange

In Germany, the euro was distributed to banks and retailers from September 2001 under the so-called "frontloading procedure". Retailers were to be involved in the exchange process by issuing euros and accepting Deutsche Marks.

From 17 December 2001, it was already possible to purchase a first euro coin mix, also known as a "starter kit", in German banks and savings banks. These starter kits contained 20 coins worth €10.23 and were issued for €20, with the rounding difference being covered by the national treasury.

In order to avoid queues at bank counters after the Christmas holidays and the turn of the year 2001/2002, it was made possible to pay at retailers in Deutsche Mark in January and February 2002 as well. Change was issued by retailers in euros and cents. In addition, euro cash came into circulation from 1 January 2002 through withdrawals at cash dispensers and bank counters. Furthermore, during the first two weeks of January there were queues at the exchange counters of banks and savings banks. From the end of January 2002, cash payments were made mainly in euros. One imponderable in the introduction of euro cash was that the nature, appearance and formats of the new banknotes were deliberately not published in advance in order to avoid counterfeiting during the introductory phase. The security features, e.g. watermark, security thread, hologram foil and microprinting, were also not disclosed in advance.

While the conversion of ATMs was largely unproblematic, the ATM industry feared a loss of revenue, since the machines accepted either euros or deutschmarks (other payment options, such as the GeldKarte, were of no significant importance at the time). Some transport companies, such as the Rhein-Main-Verkehrsverbund, had converted about half of their machines to the euro by the deadline, so that customers in many places found an 'old' and a 'new' machine. The transition was less problematic than feared, so that many machines were converted to the euro earlier than initially planned.

Conversion of accounts and contracts

Accounts with banks and savings banks could be held in euro on request from 1 January 1999. In the context of the introduction of euro notes and coins, accounts were then automatically converted to the euro on 1 January 2002; however, some institutions already carried out this conversion for all customers in December 2001. The changeover was free of charge. In the transitional years 1999 to 2001 inclusive, transfers could be made either in DM or in euro; depending on the currency in which the target account was held, an automatic conversion took place; as from 1 January 2002, transfers and cheque payments could only be made in euro.

Existing contracts remained valid. As a rule, monetary amounts were converted on 1 January 2002 (with a factor of 1.95583), so that both receivables and liabilities remained unchanged in value. Nevertheless, it was possible to settle old DM receivables in DM cash up to the end of the transitional period on February 28, 2002, within the limits of any cash holdings still available.

Cash exchange for latecomers

In Germany, the transitional period of parallel acceptance of Deutsche Mark and euro by retailers ended at the end of February 28, 2002. Since then, the exchange of Deutsche Mark into euro has been possible only at the branches of the Deutsche Bundesbank (formerly Landeszentralbanken) for an unlimited period and free of charge. As part of special promotions, some German retail chains and retailers now and then accept the Deutsche Mark as a means of payment.

Despite the simple and free exchange mechanisms, DM coins and notes worth the equivalent of €12.76 billion had still not been exchanged in July 2016. However, according to the Deutsche Bundesbank, most of this was lost or destroyed money.

The euro is thus the fifth currency in German monetary history since the foundation of the Reich in 1871, its predecessors being the gold mark, the Rentenmark (later the Reichsmark), the Deutsche Mark and the mark of the GDR (previously the Deutsche Mark and the Deutsche Notenbank mark respectively).

Austria

In Austria, the Oesterreichische Nationalbank started the frontloading of euro coins and banknotes to credit institutions on 1 September 2001. The banks were able to start supplying corporate customers and retailers with the new means of payment immediately. For this purpose, the National Bank issued cassettes with coin rolls, officially called Start Package Trade, worth 145.50 euro with an equivalent value of 2,000 schillings for the cash register equipment in the trade. Independently of this, each company could register its individual euro requirements with its credit institution.

Coin pouches, officially named Startpaket, were issued to private individuals from 15 December 2001. They contained 33 coins with a total value of 14.54 euro and an equivalent value of 200.07 shillings and were issued for 200 shillings. The general issuance of money - in particular also of the new banknotes - started on 1 January 2002.

As in Germany, the so-called dual circulation period ran in Austria from 1 January to 28 February 2002, during which it was possible to pay in cash with both currencies, i.e. either with the schilling or the euro - but also with a mixture. Although the schilling lost its validity as an official means of payment as of 1 March 2002, many shops continued to accept the schilling beyond the legally stipulated period, since schilling banknotes and coins can be exchanged for euros at the Oesterreichische Nationalbank and schilling coins at the Austrian Mint for an unlimited period and free of charge. The changeover at ATMs went largely smoothly; the banknotes dispensed there were initially only 10- and 100-euro notes. The limit on the amount of cash that can be withdrawn daily from ATMs was increased with the changeover from 5000 shillings (363.36 euros) to 400 euros. In non-cash payment transactions, the changeover of all accounts and payment orders took place automatically on 1 January 2002.

While other vending machines, such as those for cigarettes, were gradually converted from schillings to euros, the sugar, chewing gum, condom and postage lottery ticket vending machines made by Ferry Ebert were taken off the market. The company was unable to finance the conversion of the approximately 10,000 vending machines in Austria alone; its vending machines have become coveted collector's items.

As of 31 March 2010, according to Nationalbank data, shilling stocks of 9.06 billion shillings with an equivalent value of 658.24 million euro were still in circulation. Of this, 3.45 billion shillings (250.9 million euros), which can be exchanged into euros without limit, were banknotes and 3.96 billion shillings (287.5 million euros) were coins. However, the difference, about 18%, 1.65 billion shillings (119.8 million euros), is accounted for by the last two banknotes, some of which are still in circulation, with a preclusion period until 20 April 2018 and which had lost their legal tender status long before the introduction of the euro. These are the 500-schilling "Otto Wagner" banknotes and the 1000-schilling "Erwin Schrödinger" banknotes.

In order to offer Austrians, but also foreign guests, an easy way to exchange their remaining stocks of schillings into euros, the Oesterreichische Nationalbank's Euro Bus has been travelling through Austria during the summer months since 2002. A secondary purpose of the campaign is to inform the population about the security features of the euro notes.

The changeover to the euro was the sixth monetary reform or changeover in Austria's monetary history since 1816, following the Napoleonic Wars. The predecessors of the euro in Austria were the guilder, the koruna (Austria-Hungary), the schilling (First Republic), the reichsmark (after the Anschluss to the "Third Reich") and the schilling (Second Republic); in 1947 there was a currency reform with a devaluation of the schilling to one third.

Other euro area countries

For all existing participants, euro cash was introduced at the beginning of the year.

During a short transitional period after the introduction of euro cash, cash in euro and the old national currency was in circulation in each participating country. However, the former national currencies were generally no longer legal tender at this time, but were accepted on account of payment; the conversion into euro took place at the officially fixed exchange rate. The period of parallel cash circulation was set differently, for example until the end of February or until the end of June 2002. Most currencies can or could still be exchanged for euros at the respective national central bank after that date.

Exchange of old cash

In the euro countries, the handling of the former currencies is regulated differently. Even after these are no longer legal tender, there is or was the possibility to exchange them. However, the exchange periods differ:

- Notes and coins exchangeable for an unlimited period: Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania and Austria.

- Only notes exchangeable for an unlimited period, coins for a limited period: Belgium, Luxembourg, Slovakia and Slovenia (deadlines expired in each case).

- Notes and coins only for a limited period (but sometimes with different expiry dates):

- Coins and notes still exchangeable: Spain (until 30 June 2021)

- Coins no longer exchangeable: Portugal (until 28 February 2022), Netherlands (until 1 January 2032, but not guilder notes issued in transactions after 27 January 2002)

- Deadlines expired: Cyprus, Finland, France, Greece, Italy and Malta

Acceptance of the euro

Acceptance in Germany

In Germany, two and a half years after the introduction of the euro, a research team from the Ingolstadt University of Applied Sciences presented a study on its acceptance by the German population. According to the study, at the time of the survey (2004) almost 60% of the German population had a positive attitude towards the euro. However, many of those surveyed mourned the loss of the D-Mark. Many of those surveyed also converted prices from euros into Deutschmarks, more frequently for higher amounts than for lower ones. For all prices, 48% of respondents converted, but for prices above 100 euros, 74% still did. This was facilitated by the simple conversion factor (almost 1:2, exactly 1:1.95583). In addition, however, the population also associates the introduction of the euro with a general increase in prices, which was carried out by parts of the retail trade. In some of the euro countries (e.g. France and the Netherlands), price increases during the period of introduction of the euro were prohibited by law; in Germany, retailers had relied on a voluntary commitment. The euro is becoming much more popular for foreign travel and holidays within its area of validity. The improved price comparison within Europe is also noted positively. According to the above-mentioned study, many respondents also welcome the fact that the common EU currency has created a counterweight to the US dollar and the yen.

According to the Eurobarometer 2006, a relative majority of 46% of the German population thought that "the euro is good for us, it strengthens us for the future", while 44% thought that the euro "tends to weaken the country". In 2002, euro supporters (39%) were still in the minority compared to eurosceptics (52%). At the end of 2007, however, a study by Dresdner Bank on behalf of the Forschungsgruppe Wahlen showed a drop in Germans' acceptance of the euro to 36%, compared with 43% in 2004.

According to Eurobarometer 2014, a clear majority of Germans (74%) now support the euro, while a minority of 22% reject it.

Acceptance in Austria

According to Eurobarometer, Austrians have a more positive attitude towards the euro than Germans. In 2006, 62 % of the Austrian population were of the opinion that "the euro is good for us, it strengthens us for the future", while 24 % were of the opinion that the euro rather weakens the country. In Austria, the euro supporters (52%) were already in the majority in 2002 compared to the euro sceptics (25%).

Acceptance in Latvia

In the course of the introduction of the euro in Latvia, according to the market research company SKDS, only 22% of the Latvian population approved, while the majority of 53% were against. In the following years, this ratio changed significantly: in 2018, 83% of Latvians were in favour of the euro.

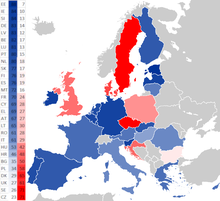

Approval of the euro in EU member states. (As of March 2018) Rejection of the euro Approval of the euro

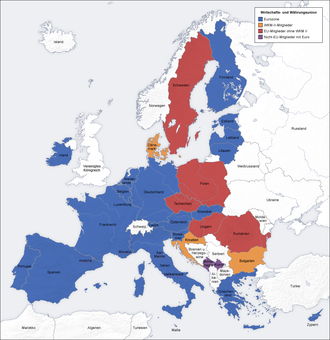

Map of European countries with reference to the euro EU countries with euro EU countries in ERM II EU countries outside ERM II Non-EU members with Euro

German Starter Kit

Austrian start-up package

Euro sign as a work of art by Ottmar Hörl at Willy-Brandt-Platz in Frankfurt am Main

European Central Bank

→ Main article: European Central Bank

The euro is controlled by the European Central Bank (ECB) in Frankfurt am Main. This took up its work on 1 June 1998. However, responsibility did not pass from the national central banks (NCBs) to the ECB until the start of European Monetary Union (EMU) on 1 January 1999. In addition to maintaining price stability, as laid down in Article 105 of the EC Treaty, the ECB also has the task of supporting the economic policies of the Member States. Other tasks of the ECB are to define and implement monetary policy, manage the official foreign reserves of the Member States, conduct foreign exchange operations, supply the economy with money and promote smooth payments. In order to preserve the ECB's independence, neither it nor any of the NCBs may receive or seek instructions from any of the governments of the Member States. This legal independence is necessary because the ECB has the exclusive right to issue banknotes and thus has influence over the money supply of the euro. This is necessary to avoid the temptation to make up for any budgetary shortfalls with an increased money supply. This would diminish confidence in the euro and the currency would become unstable.

The European Central Bank, together with the national central banks such as the Deutsche Bundesbank, forms the European System of Central Banks and has its seat in Frankfurt am Main. The decision-making body is the Governing Council, which is made up of the Executive Board of the ECB and the governors of the national central banks. The Executive Board in turn consists of the President of the ECB, his Vice-President and four other members, all of whom are regularly elected and appointed by the members of the EMU for a term of eight years, re-election being excluded.

The European Central Bank (ECB) in Frankfurt is the cross-border central bank of the euro area (since 2014 ECB headquarters)

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the currency of the countries in the eurozone?

A: The currency of the countries in the eurozone is the Euro.

Q: How many different banknotes are there for euro?

A: There are seven different banknotes for euro, each one with a different colour, size and face value.

Q: What are the eight amounts of coins available for euro?

A: The eight amounts of coins available for euro are €0.01, €0.02, €0.05, €0.10, €0.20, €0.50, €1 and €2.

Q: When did 12 countries adopt euro notes and coins as their only money?

A: In 2002, 12 countries adopted euro notes and coins as their only money.

Q: Are there any differences between designs on euro coins from different countries?

A: Yes, one side of each coin is unique to each country while the other side is shared by all countries who mints them throughout the eurozone despite the country-specific symbol on it's backside.

Q: When did Slovenia become part of using euros?

A: Slovenia became part of using euros in 2006 when they adopted it as their official currency.

Q: Are there any new European countries planning to adopt Euro also?

A:Yes ,the ten new European countries that entered into European Union in May 2004 are planning to adopt Euro also but first they must meet some conditions to show that they have stable economies before doing so .

Search within the encyclopedia