Eugenics

![]()

This article is about the human genetically oriented population policy called eugenics; for other meanings see Eugenics (disambiguation).

Eugenics (from the ancient Greek εὖ eũ 'good', and γένος génos 'gender') or eugenetics, in German also Erbgesundheitslehre, in the National Socialist era (since also called Erbpflege) or in Germany usually synonymous with Rassenhygiene (cf. Nationalsozialistische Rassenhygiene), refers to the application of theoretical concepts or the findings of human genetics to population and health policy or the gene pool of a population with the aim of increasing the proportion of positively evaluated hereditary characteristics (positive eugenics) and decreasing the proportion of negatively evaluated hereditary characteristics (negative eugenics). of human genetics to population and health policy or the gene pool of a population with the aim of increasing the proportion of positively evaluated hereditary traits (positive eugenics) and reducing the proportion of negatively evaluated hereditary traits (negative eugenics). The British anthropologist Francis Galton (1822-1911) coined the term as early as 1869 and 1883 for the improvement of the human race or "the science concerned with all influences which improve the innate characteristics of a race". Around 1900, the counter term dysgenics also emerged, meaning "the study of the accumulation and spread of defective genes and traits in a population, race or species".

Eugenic considerations were widespread and widely discussed in the first half of the 20th century. In Great Britain, the Boer War in particular, in which serious problems due to the lack of suitable recruits, fears of a loss of significance in foreign policy and domestic degeneracy ideas came together in the environment of the first English war fought under the conditions of mass democracy, led to the formation of an active eugenics movement. Among its well-known representatives were Ronald Aylmer Fisher, Margaret Sanger, Julian Huxley, D. H. Lawrence, George Bernard Shaw, and H. G. Wells. A distinction was made between active and passive eugenics. In the popular socio-political discussion, biologistic interpretations of the theory of heredity according to Mendel as well as behavioral interpretations in the tradition of Lamarckism still play an important role today. Corresponding viewpoints have found expression in the legislation of a number of industrialized countries on immigration, school policy, and the treatment of minorities. After a long period of liberalism, the British eugenics movement stood for an active role of the state in these policy areas and also appealed to classical social democratic representatives, for example in the Fabian Society.

In classic immigration countries such as Canada and Australia, it was above all the treatment of immigrants and ethnic minorities that was viewed from a eugenic point of view. Many of the measures that were considered progressive at the time are today perceived as racially motivated and regretted. In Japan and Germany, both former agrarian states with few immigrants at the time and experiencing a period of rapid growth, the term was subsumed and widely adopted under the catchphrases racial hygiene and blood purity (Junketsu 純血 pure and Konketsu 混血 impure blood, respectively).

National Socialist racial hygiene served to justify the murder of the sick during the National Socialist era in the context of the "extermination of life unworthy of life", for example in "Aktion T4" and "child euthanasia", and for human experiments in concentration camps. With regard to the implementation of "racial hygienic reforms", the National Socialist racial hygienist Fritz Lenz had advocated the use of the word "racial hygiene" instead of "eugenics". In the postwar period, the term eugenics was associated by lay people and experts alike with these and other crimes committed under National Socialism, as well as with war crimes committed by the Japanese armed forces in World War II, especially by units of the Imperial Japanese Army. In Germany in particular, "racial hygiene" and the term eugenics were henceforth shunned.

At the end of the 20th century, due to advances in both genetics and reproductive medicine, the ethical and moral significance of eugenic issues was again more widely discussed in the German-speaking world. In the process, the term is occasionally also used as a fighting concept. The almost unbroken tradition in the English-speaking world followed this development only later. The important British Eugenics Society was renamed the Galton Institute in 1989.

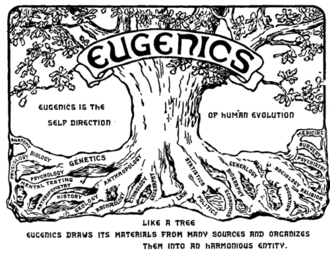

"Eugenics is the self-direction of human evolution": logo of the Second International Eugenics Conference, 1921.

Basics

Self-image

Galton understood eugenics as a science in the service of a healthier humanity. Even its earliest proponents regarded efforts to achieve social balance, to civilize social crises, and to equalize life chances as detrimental to public health and "biological higher development. In order to reduce or prevent the offspring of sick people who were at the same time considered inferior, and to open up better future opportunities for healthy and thus supposedly superior people, they called for political intervention. Their main representatives not only ensured the theoretical foundation and dissemination, but also the political implementation of their demands through appropriate health, social and population policies.

Ideas derived from animal breeding were transferred to humans: by favouring the reproduction of healthy people - e.g. by rewarding high numbers of children - and preventing the reproduction of sick people - e.g. through contraception, birth control and forced sterilisation - the genetic make-up of the population was to be improved in the long term and hereditary diseases reduced. Such ideas were strongly motivated by the degeneration of society or of the "races" predicted by various Social Darwinist movements, which they expected to occur due to an assumed elimination of natural selection by civilizing influences.

Application of eugenics

Eugenic goals were methodically pursued in three ways,

- On the one hand, as authoritarian and legally enforced state requirements, as in the case of the forced sterilization of individuals or entire groups of people, and by means of eugenically justified or concealed restrictions on immigration, education and freedom of movement,

- Furthermore, as a regulation recommended by state or private institutions, for example in the case of preliminary examinations of pregnant women,

- lastly, as a personal decision on the part of the couple, for example when hereditary diseases are known or become known in connection with human genetic counselling.

The French philosopher Michel Foucault emphasized the character of eugenics, racial hygiene and population policy as a new power technique, which he called biopolitics. Foucault saw the initial grounds of this new power technique as early as the second half of the 18th century with the rise of the bourgeoisie and its intense preoccupation with sexuality, which was increasingly subjected to state regulation.

"Structural Elements of the Racial-Hygienic Paradigm."

According to Hans-Walter Schmuhl, four structural elements characterize the "racial hygiene paradigm."

- "Racial hygiene was based on the monistic axiom fundamental to the theorizing of Social Darwinism, according to which social events are based on natural laws - namely, the laws of development demonstrated for Darwinian evolution and selection theory. Based on this premise, Social Darwinism constituted itself as a natural theory of society.

- Racial hygiene presupposed the primacy of the selection principle characteristic of the selectionist phase of Social Darwinism, which was associated with a relativization of the teleological dimension of the evolution theorem typical of the evolutionist phase of Social Darwinism.

- Racial hygiene received dynamizing impulses from the dichotomy, the incompatibility of degeneration theories and breeding utopias.

- On the basis of a bioorganismic metaphor, racial hygiene developed a decided anti-individualism that relativized the value of human life to society understood as a higher level of being."

A central component of the racial-hygienic paradigm was the concept of degeneration, since "the carriers of 'inferior genetic material' multiplied more rapidly than the carriers of 'superior genetic material', so that from generation to generation there would have to be a progressive erosion of genetic substance - in relation to the population as a whole", which explains the "apocalyptic population discourses" in the first half of the 20th century.

Backgrounds

Mastermind

Modern eugenics has its origins in the 19th century. Ideas, measures and justifications of state and social interventions and influences on reproduction have been known since antiquity. They can already be found in Plato's Politeia, but here they are limited to state selection and education of so-called "guardians" and are not aimed at evaluating their genetic make-up.

In the Renaissance, corresponding lines of thought can be found in the social utopian writings Utopia by Thomas Morus, Nova Atlantis by Francis Bacon and La città del Sole by Tommaso Campanella.

Gobineau

From 1852 to 1854, the French writer Arthur de Gobineau published a four-volume Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines (Attempt on the Inequality of the Human Races), in which he introduced the concept of miscegenation and adopted the concept of the Aryan, common in linguistics, into the field of racial theories. He postulated a Nordic-Aryan original race and propagated its preservation or restoration through human breeding and selection. He considered the mixing of races to be harmful, which was plausible at the time because, according to a common hypothesis (blending inheritance), heredity was thought to be tied to the blood, in the progressive mixing of which valuable dispositions would be lost through dilution. Gregor Mendel's discovery that the hereditary material does not behave like a liquid, but consists of mutually independent hereditary units, was not acknowledged by experts until 1900 and then established itself as the prevailing doctrine over the course of several decades.

Gobineau's theses met with a wide response in the German translation by Karl Ludwig Schemann, gained additional popularity in the nineteenth-century foundations of Houston Stewart Chamberlain, and spread through Cecil Rhodes, the All-German Association, and the program of the Deutschvölkische Partei, founded in 1914, to National Socialism.

Social Darwinist theories of society

Charles Darwin published his book The Origin of Species by Natural Selection (the German translation) in 1859. In it, he described his theory of natural selection of the best-adapted animal and plant species, constantly renewed from generation to generation. This, he argued, was the main driving force of evolution towards new species. In 1871 he published his work The Descent of Man and Sexual Selection. With this, Darwin shared the view, widespread since Malthus, that welfare state measures and natural selection were incompatible.

Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) adopted Darwin's term struggle for life (often translated as "struggle for existence") and coined the term Survival of the Fittest (not "survival of the fittest", but "of those best adapted to changing environmental conditions"), which was often erroneously attributed to Darwin and was already controversial at the time of its emergence.

In his work Bau und Leben des sozialen Körpers (1875-78), Albert Schäffle (1821-1903) sketched a picture of a social order that resembles the anatomy of the human body in all its parts and manifestations. He concluded from this, among other things, the hopelessness of social democracy (book title 1885), which was based on an illusory principle of equality and image of man.

The basic idea of Social Darwinist social theories was that the natural selection of the most suitable for survival would be hindered by medicine and social welfare aimed at indiscriminate life support. Proponents of this assumption claimed that social policies interfering with "natural selection" would lead to "counter-selection" and thus to a gradual weakening of public health. One of the masterminds of eugenics was the zoologist Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919). He was of the opinion that "the history of peoples [...] can largely be explained by natural breeding, but that there is also artificial breeding". As an example he cites the Spartans, who killed weak, sick or malformed newborns: "Certainly the people of Sparta owe their rare degree of manly strength and rugged heroism largely to this artificial selection or breeding." This comparison would later be taken up by the racial hygienists and also by Hitler.

In 1899, the philosopher Heinrich Rickert (1863-1936) coined the term biologism for this, which he critically distinguished from biology as a politicizing ideology (Kulturwissenschaft und Naturwissenschaft 1899; Der Biologismus und die Biologie als Naturwissenschaft 1911).

Eugenics in the Labour Movement

Eugenic tendencies also found their way into the workers' movement. According to Reinhard Mocek, the early workers movement tried to reassure itself of its goals in a social-philosophical and at the same time biologistic way. In this sense there was a "proletarian biologism" or a "proletarian liberation biology". Early approaches oriented towards phrenomesmerism, Franz Anton Mesmer and Franz Joseph Gall had been replaced by neo-Lamarckism in August Bebel's time. With Karl Kautsky, a "Copernican turn" in the discussion in the workers' movement had become apparent. Bourgeois thought had gained increasing influence; the restoration of the natural rights of human beings had now been replaced by the reorganization of human existence. The fact that Kautsky dared to address questions such as degeneracy and overpopulation contributed to the emergence of a reformist social policy.

A number of members of the British Fabian Society were also eugenicists. The so-called Minority Report by Beatrice Webb and Sidney Webb, 1st Baron Passfield was, among other things, the basis of the first programme of the Labour Party and eugenically influenced. This was also true of key figures who shaped both the British and Swedish welfare states, such as Richard Titmuss and Gunnar Myrdal.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is eugenics?

A: Eugenics is a social and political philosophy that tries to influence the way people choose to mate and raise children, with the aim of improving the human species.

Q: What are some basic ideas behind eugenics?

A: The basic ideas behind eugenics include that in genetics, what is true of animals is also true of man, and that characteristics are passed on from one generation to the next in heredity.

Q: What are negative and positive eugenics?

A: Negative eugenics aims to cut out traits that lead to suffering by limiting people with those traits from reproducing, while positive eugenics aims to produce more healthy and intelligent humans by persuading people with those traits to have more children.

Q: How has eugenics been used in the past?

A: In the past, many ways were proposed for implementing eugenic principles, and it was sometimes used to justify discrimination and injustice against people who were thought to be genetically unhealthy or inferior.

Q: Is there controversy surrounding eugenics?

A: Yes, because of its history of being used as a justification for discrimination against certain groups of people.

Q: Are all interpretations of eugenics similar?

A: No, different people interpret it differently depending on their own beliefs and values.

Search within the encyclopedia