Ernest Mason Satow

Sir Ernest Mason Satow (b. June 30, 1843 in Clapton (North London); † August 26, 1929 in Ottery St Mary near Exeter, Devon) established relations between Britain and the emerging modern Japan as a British diplomat and scientist. He was Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George and a member of the Privy Council.

Satow was the son of a German-born father (Hans David Christoph Satow, born in Wismar, British citizen from 1846) and an English mother (Margaret Satow, née Mason). He received his education at Mill Hill School and University College London. He is particularly known for his book A Diplomat in Japan, in which he describes the years 1862 to 1869, when Japan was making the transition from the Tokugawa Shōgunate to the restoration of imperial power (Meiji Restoration).

The 19-year-old had been working as an interpreter in Japan for barely a week when, on September 14, 1862, British merchant Charles Lennox Richardson was killed on the road between Tōkyō and Kyōto for remaining seated in the saddle of his horse in the face of the passing Daimyō of Satsuma, Shimazu Hisamitsu (Namamugi Incident). Satow was aboard one of the British ships that shelled Kagoshima in 1863 to punish Hisamitsu for Richardson's murder and his refusal to pay the compensation demanded. Immediately before this, he met for the first time with Itō Hirobumi and Inoue Kaoru of Chōshū. He also maintained relations with numerous other influential figures in Japan, including Saigō Takamori of Satsuma. In 1864, Satow was part of the allied force of Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, and the United States that enforced the right of passage for foreign ships through the Kammon Strait between Honshū and Kyūshū by attacking Shimonoseki. Furthermore, he traveled the Japanese hinterland together with A. B. Mitford and the draftsman and illustrator Charles Wirgman.

With his excellent knowledge of the Japanese language, Satow soon made himself indispensable for intelligence work, as well as British minister Sir Henry Parkes' negotiations with the weakening Tokugawa Shōgunate and the powerful clans of the Satsuma and Chōshū fiefdoms. He was promoted to chief interpreter, then secretary of the British legation in Japan. In addition, he began writing translations and newspaper articles on subjects concerning Japan as early as 1864. In 1866, three articles by Satow appeared anonymously in the Japan Times, whose Japanese translation under the title Eikoku Sakuron (roughly "British Political Principles") apparently made an impression on many Japanese and probably contributed to the acceleration of the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Satow pointed out that the Shōgun had concluded agreements with Britain and other states on behalf of Japan without even mentioning the existence of the Tennō, and therefore cast doubt on their validity. He accused the Shōgun of deception and demanded clarification as to who was the actual head of state of Japan, as well as a revision of the treaties to reflect political reality. In A Diplomat in Japan, he later admitted that the publication of these articles had been "in stark contrast to the rules of (diplomatic) service," because interference in the internal affairs of the country in which he was serving was not a diplomat's right.

In 1869 he returned home to England for an extended vacation, but traveled again to Japan in 1870. Satow was a founding member of the Asiatic Society of Japan, established in Yokohama in 1872, whose mission was the thorough study of Japanese culture, history, and language (i.e., Japanology). During the 1870s, he gave several lectures for the society, and some of his publications can be found in the reports of the Asiatic Society, which is still active today.

After years of service in Siam (1884-1887, during which time he was promoted from the consular to the diplomatic corps), Uruguay (1889-1893), and Morocco (1893-1895), Satow returned to Japan on 28. He returned to Japan as envoy extraordinary and plenipotentiary general on July 28, 1895, and spent five more years in Tōkyō, interrupted by his presence in London for Queen Victoria's diamond coronation jubilee in 1897. In August of that year, he met the queen in person at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight.

On April 17, 1895, the Shimonoseki Peace Treaty had been signed between Japan and China, and Satow was able to follow closely the steady buildup of Japanese land and naval forces in retaliation for the humiliating defeat of April 23, 1895, at the hands of Russia, Germany, and France ("Triple Intervention"). In his position, he was also able to observe the end of extraterritoriality for British citizens in Japan in 1899, sealed by the Anglo-Japanese Trade and Navigation Agreement, which came into being in London on July 17, 1894.

The honor of being appointed the first official British ambassador to Japan was not bestowed on Satow, but only on his successor Sir Claude Maxwell MacDonald in 1905. Satow served as British envoy to Peking from 1900 to 1906. He was involved in the negotiations that led to the final protocol on compensation payments to the victorious Allies after the Boxer Rebellion, and witnessed from Beijing the Russian defeat in the 1904-05 war with Japan. His appointment to the Privy Council, the British secret council of state, followed in 1906, and in 1907 he was Britain's second plenipotentiary to the 2nd Hague Peace Conference, which adopted the Hague Land Warfare Regulations.

In accordance with his will, Satow's extensive diaries and correspondence (the Satow papers) are preserved in the Public Record Office at Kew (West London), and of his rare Japanese books, many are now in the collection of Cambridge University Library. After retiring to Ottery St Mary (Devon) in 1906, he devoted himself mainly to topics of diplomacy and international law. He is less well known in Britain than in Japan, where he is recognized as perhaps the most important foreign observer of the Bakumatsu and Meiji periods.

As a diplomat serving in Japan, he was unable to marry his Japanese partner, Takeda Kane (武田 兼), with whom he had two sons, Eitarō and Hisayoshi (久吉). At the instigation of his granddaughters, the letters of the Takeda family, including numerous correspondences between Satow and his family, were added to the Yokohama Historical Archives.

Satow's wife Kane, 1870

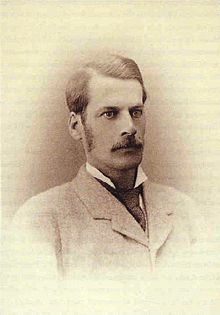

Ernest Satow

Search within the encyclopedia