Equus (genus)

![]()

This article is about the horse genus. For the domesticated horse, see domestic horse, for other meanings horse.

The horses (Equus) are the only recent genus of the family Equidae. The genus includes the wild horses (the Przewalski's horse and the now extinct tarpan), the various wild ass forms (the African and Asian asses and the kiang, respectively), and at least three species of zebra (the steppe, mountain, and Grevy's zebra). It also includes domestic forms domesticated from wild animals. The number of species and their delimitation from one another remain controversial to this day. A total of seven or eight species are often distinguished, the majority of which are endangered. The animals now live in sub-Saharan Africa and southern and central and eastern Asia. The inhabited habitats consist of open, often grassy landscapes, which can sometimes be very dry to desert-like. Horses are adapted to these regions by their strong build and long, slender limbs. The distinguishing feature of the species is also found on the legs, as both the front and hind feet each have only one toe, which is covered by a broad hoof. The reduction in the number of toes, which also earned the horses the higher-ranking designation of "solipeds", enables fast and low-friction locomotion in the steppe and savannah regions.

In general, horses are social animals. Two group types can be distinguished in the social community: one with groups of mothers and young animals and stallions living individually, and a second with larger groups of mares and young animals that also include one or more males, the so-called "harems". The formation of one or the other basic type is usually dependent on external factors. These include above all the food supply, which can be constant over the year or - due to the stronger influence of seasons - also changing. The main food of the animals consists of grasses, occasionally they also eat leaves and twigs. To chew the hard grass food, horses developed molars with extremely high tooth crowns, which is considered another typical characteristic of the species. The less efficient gastrointestinal tract compared to other ungulates causes the horses to spend most of their active time eating. Stallions mate with several mares, while mares have either one or more stallions as mating partners, depending on the social group type in which they live. In most cases, a single foal is born, which is independent after a maximum of six years. Both the male and female offspring then leave the parental group.

Horses have a great importance in the history of human development. In prehistoric times they were used as an important source of raw materials and food. In the course of settling down, two species were domesticated. The domestic horse developed from the wild horse, the domestic donkey from the African donkey. Both types of domestic animal play an important role as riding and pack animals and spread worldwide in the wake of man. The systematic study of the genus began in 1758 with the establishment of the generic name Equus. In the following period, various subdivision proposals were made, most of which, however, did not hold much water. From a phylogenetic perspective, horses are the most recent member of a family evolutionary process that spans a good 56 million years. The earliest representatives of the horse genus appeared in North America in the Pliocene, about three and a half million years ago. Only a little later, these early horses had colonized Eurasia and Africa. The American branch of the horse became extinct about 10,000 years ago.

Features

Habitus

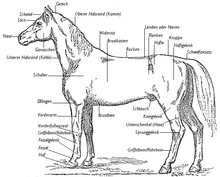

Horses are generally stocky animals with a cylindrical body and long neck, a comparatively large head and long limbs. Size and weight vary from species to species: Overall, the animals reach head-torso lengths of 200 to 300 cm, the tail becomes 30 to 60 cm long. Shoulder height varies between 110 and 140 cm with a weight of 200 to 275 kg in the smaller species such as the Asian (Equus hemionus) and the African donkey (Equus asinus), the largest recent species, the Grevy's zebra (Equus grevyi) grows up to 150 cm high at the withers and weighs between 350 and 430 kg, in exceptional cases up to 450 kg. The sexual dimorphism is only slightly developed, males surpass females by only about 10% in body weight. On the head, especially the facial area is elongated. The eyes are situated on the side of the head, the ears are long and mobile. The coat is dense and often short, most species have longer hair on the neck, mop of hair and tail, called long hair or mane. The coat coloration in some species is gray or brown on top and whitish-gray on the underside. Stripes on shoulders and limbs may be present in several species. The three zebra species are distinguished by their striking black and white coat. Chestnuts or "night eyes," callus-like dark spots on the legs, form a distinctive feature. Zebras and wild asses have these mainly on the front legs, wild and domestic horses often have them on all four legs. Size and shape vary individually. These may be vestigial glands or remnants of a wrist and ankle pad. The front and hind feet end in broad hooves, of which horses have only one per limb ("one hoof"). The "hoof shoe" completely covers the last phalanx.

Skull and dentition characteristics

Horses have a massive head, the facial skull is strikingly elongated and is formed mainly by the upper jaw. The intermaxillary bone is also elongated. The nasal bone has a long narrow shape. The orbit is set far back and lies behind the teeth. It is completely enclosed by bone. The posterior part of the skull is comparatively short, but the brain capsule is relatively large. A peculiarity of horses is found in the air sac, which is an outpouching of the eustachian tube below the base of the skull. The paired opening has a capacity of 350 to 500 ml each. Originally interpreted as helping to cool the brain, according to Horst Erich König and Klaus-Dieter Budras, among others, the air sac probably serves - like the paranasal sinuses - rather to reduce the specific weight of the skull. The lower jaw is also massively shaped. The mandibular joint lies high, the mandibular branch is enlarged. At the rear end a strong angular process appears, to which the masseter muscle anchors.

Horses have three incisors, one canine and six to seven posterior teeth per half of the jaw. The dental formula is:

Limbs

One of the most characteristic features of horses is the reduction in the number of toes. Thus, all species living today have only one functional toe (monodactyly). This is the third toe, the remaining toes are degenerated and preserved on the skeleton of the limbs as rudimentary grip bones. The grip bones are not functionless, however, as they provide an important support function for the tendons that connect the lower limbs to the fore and hind feet. The metacarpals are shorter than the metatarsals, which also affects the overall length of the fore and hind legs. Horses, like all odd-toed ungulates, have a saddle-shaped talonavicular joint-the hock joint between the hock bone (talus) and the navicular bone (naviculare)-that significantly limits mobility. The ulna is greatly reduced and fused to the radius in the lower half. Similarly, the lower end of the fibula fuses completely with the tibia. The femur is comparatively short, though provided with a large bony process (trochanter tertius) at the upper part of the shaft below the condyle. The clavicle is missing.

Internal anatomy

The heart of horses, as in all vertebrates, circulates blood throughout the body as a muscle pump. It is more globoid in shape than the human heart and consists of four chambers: the left and right atria and the left and right ventricles. The average adult horse has a heart weighing 3.4 kg, or about 0.6 to 0.7% of body weight. In domestic horses, it may increase somewhat in size in response to conditioning. Circulatory capacity is determined in part by the functional mass of the heart and spleen. The heart rate in animals at rest is 15 to 45 beats per minute. It can increase threefold during strenuous activity. Studies on zebras show that young animals generally have a higher heart rate than old animals. In contrast, greater muscle mass results in slower heart rates.

Horses, like all odd-toed ungulates, are terminal intestinal fermenters, which means that most digestion takes place in the intestinal tract. The stomach is - in contrast to that of ruminants - always simple and single-chambered with a length of about 74 or 14 cm (measured over the outer and inner curvature) and a volume of 0.8 l in the case of the domestic donkey. Fermentation takes place in the very large appendix and the double-looped, 2 to 4 m long ascending colon. The pH values in the small intestine increase from anterior to posterior and range from 6.3 to 7.5, dropping again to about 6.7 in the following large intestine. Similarly, the individual proportion of microflora increases in the small intestine, amounting to about 2.9 × 106 per gram (wet weight) in the anterior section and about 38.4 × 106 in the posterior. In the caecum and colon they amount to 25.9 and 6.1 × 106, respectively. The caecum can hold up to 33 l of filling, the entire small intestine up to 64 l, and the colon up to 96 l. Altogether, the intestinal tract becomes up to 18 m long with the house-donkey and up to 30 m with the house-horse.

Horses differ from other mammals in the structure of the ovary: The ovarian tissue with the follicles, usually called the "cortex", is located inside the organ, whereas the vascular ovarian medulla is located outside. The ovarian cortex reaches the surface only at one point. This point is also visible from the outside as a retraction and is called the "ovulation pit" (Fossa ovarii); ovulation can only occur at this point. The follicle, which is ready for ovulation, reaches a diameter of 5 cm and is thus more than twice as large as that of a bovine. Male animals have a scrotum but, like all odd-toed ungulates, no penis bone. The penis itself is about 35 cm long with a diameter of about 5 cm in the house donkey when it is not erect. The testicles weigh between 123 and 136 g each. Their weight increases considerably during the mating season, in the case of the steppe zebra, for example, it increases from about 268 to 345 g for both testicles combined. The increase in size is all the more pronounced the more strictly the reproductive phase is seasonally limited. The kidneys lie below the lumbar vertebrae and weigh 240 to 270 g in the domestic donkey, in the domestic horse they reach double to triple this weight.

Chromosome number

The chromosome number of horse species varies from 2n = 66 to 2n = 32:

| 2n = 66 |

| 2n = 64 |

| 2n = 62 |

| 2n = 54–56 |

| 2n = 50–52 |

| 2n = 46 |

| 2n = 44 |

| 2n = 32 |

The span in E. hemionus as well as in E. kiang is explained by Robertson translocation.

.jpg)

Heart of a horse - clarified preparation for visualization of anatomical structures

Skull of an Asian donkey

Molar teeth of the extinct Equus mosbachensis with the characteristically strongly folded enamel

Anatomy of a stallion

A short standing-mane is characteristic for Przewalski-Horses.

Range and habitat

The wild forms of the recent horse species still live in eastern and southern Africa and in the central regions of Asia. As a habitat, horses prefer open terrain. They are found in savannahs and steppes, but also in drier habitats such as semi-deserts and deserts. Habitats, however, do not only include uniform grassy areas, but in some cases also include scrub and forest landscapes. The use of closed habitats depends in particular on how well the individual species can utilize leafy food. The influence of predators also plays a role. Furthermore, the different regions in the range of today's horses are subject to seasonal changes due to varying precipitation (rain in the more tropical and snow in the more temperate climate zones). The presence of available water sources is also an important criterion for the presence of horses in a given area.

Over the last millennia, the range of horses has declined significantly. Until the end of the Pleistocene, they were widespread over large parts of Eurasia, Africa and America. They became extinct in the Americas about 10,000 years ago for reasons that are not well understood. Explanations range from hunting by newly immigrated humans to climatic changes after the end of the last ice age to epidemics or a combination of these factors. In South America, at least, the range of horses began to decline rapidly in the late Pleistocene with the presence of the first early human colonizers. In parts of Europe, too, individual populations probably became extinct about 10,000 years ago. In North Africa and West Asia they were probably wiped out in ancient times - only in Iraq and Iran did a population of the Asian donkey persist into the 20th century. In eastern Europe, the last wild horse species - the Tarpan (Equus ferus) - became extinct in the 19th century.

In contrast, the domestic horse and donkey have been dispersed worldwide by humans, and feral populations of both forms exist in some countries. The largest number of feral domestic horses and donkeys each live in Australia, but they can also be found in the USA and other countries.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the genus of mammals in the family Equidae?

A: The genus of mammals in the family Equidae is Equus.

Q: How many living species are there?

A: There are seven living species.

Q: What type of environment do equines prefer?

A: Equines prefer grasslands and can live on low-quality vegetation.

Q: How do equines communicate with each other?

A: Equines communicate with each other visually and vocally.

Q: Are wild equine populations widespread?

A: Feral equine populations are widespread, but wild equines are found only in Africa and Asia.

Q: What type of social system do wild horses typically have? A: Wild horses typically have either a harem system or a territorial system where males control territories with resources that attract females.

Q: Where did the one-toed horses originate from? A: The one-toed horses originated from smaller three-toed horses which lived more in forests and wooded savannahs.

Search within the encyclopedia