Encyclopedia

An encyclopedia ( ![]() ), formerly also from French: Encyclopédie (from ancient Greek ἐγκύκλια παιδεία enkýklia paideía, German 'circle of sciences and arts which every free Greek had to pursue in youth before entering civil life or devoting himself to special study', i.e. what we now call 'basic education, general education, general training'), is a particularly comprehensive reference work. The term encyclopaedia is intended to indicate comprehensiveness or a wide range of topics, as in a person said to have encyclopaedic knowledge. A summary of all knowledge is presented. Accordingly, the encyclopedia is an overviewing arrangement of the knowledge of a certain time and space, which presents interrelationships. In addition, works that deal with only a single subject or subject area are called specialized encyclopedias.

), formerly also from French: Encyclopédie (from ancient Greek ἐγκύκλια παιδεία enkýklia paideía, German 'circle of sciences and arts which every free Greek had to pursue in youth before entering civil life or devoting himself to special study', i.e. what we now call 'basic education, general education, general training'), is a particularly comprehensive reference work. The term encyclopaedia is intended to indicate comprehensiveness or a wide range of topics, as in a person said to have encyclopaedic knowledge. A summary of all knowledge is presented. Accordingly, the encyclopedia is an overviewing arrangement of the knowledge of a certain time and space, which presents interrelationships. In addition, works that deal with only a single subject or subject area are called specialized encyclopedias.

The meaning of the term encyclopaedia is fluid; encyclopaedias stood between textbooks on the one hand and dictionaries on the other. The oldest completely preserved encyclopaedia is considered to be the Naturalis historia from the first century after Christ. It was above all the great French Encyclopédie (1751-1780) that established the term "encyclopaedia" for a non-fiction dictionary. Because of their alphabetical arrangement, encyclopedias are often called lexicons.

The present form of the reference work has developed mainly since the 18th century; it is a comprehensive non-fiction dictionary on all subjects for a wide readership. In the 19th century, the typical neutral, factual style was added. Encyclopedias became more clearly structured and contained new texts, not mere adoptions of older (foreign) works. One of the best-known examples in the German-speaking world was for a long time the Brockhaus Encyclopaedia (from 1808), in English the Encyclopaedia Britannica (from 1768).

Since the 1980s, encyclopedias have also been offered in digital form, on CD-ROM and on the Internet. Some of these are continuations of older works, others are new projects. A particular success was the Microsoft Encarta, first published on CD-ROM in 1993. Wikipedia, founded in 2001, has become the largest Internet encyclopaedia.

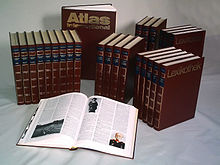

Bertelsmann Lexikothek in 26 volumes, in the edition of 1983

Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, 4th edition, volumes 1-16 (1885-1890)

Nouveau Larousse illustré , 1897-1904

The Naturalis historia of the elder Pliny in a richly illustrated edition of the 13th century

Subject Encyclopedias

The word general in general reference work refers to both the general audience and the generality (universality) of the content. Subject encyclopedias (also called specialty encyclopedias) are limited to a specific subject, such as psychology, or a subject area, such as dinosaurs. Often, though not necessarily, they appeal to a specialist audience rather than a general audience, because specialists are particularly interested in the subject. To distinguish it from the subject encyclopedia, the general encyclopedia is sometimes called the universal encyclopedia. If, however, an encyclopedia is defined as a reference work covering all subjects, then universal encyclopedia is a pleonasm and subject encyclopedia is an oxymoron.

Although most subject encyclopaedias, like general encyclopaedias, are arranged alphabetically, subject encyclopaedias have retained a somewhat stronger thematic arrangement. However, subject-limited reference works in thematic arrangement are usually given the designation handbook. Systematic arrangement is appropriate when the subject itself already strongly follows a system, such as biology with its binary nomenclature.

Perhaps the first specialized encyclopedia can be considered the Summa de vitiis et virtutibus (12th century). In it, Raoul Ardent treated theology, Christ and redemption, practical and ascetic life, the four main virtues, human behavior.

With a few exceptions, subject encyclopaedias were produced mainly from the 18th century onwards, in the field of biography, such as the Allgemeines Gelehrten-Lexicon (1750/1751). Subject encyclopedias often followed the rise of the corresponding subject, such as the Dictionary of Chemistry (1795) in the late 18th century and many other chemistry dictionaries thereafter. The wealth of publications was only comparable in the field of music, beginning with the Musikalisches Lexikon (1732) by the composer Johann Gottfried Walther. In its field, Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft (1837-1864, 1890-1978) is unparalleled.

One of the best-known popular encyclopaedias was Brehms Thierleben, founded by the non-fiction author Alfred Brehm in 1864 and published by the Bibliographisches Institut, which also published Meyer's Konversations-Lexikon. The large edition from the 1870s already had 1,800 illustrations on more than 6,600 pages and additional pictorial plates, which were also available separately, some of them colored. The third edition in 1890-1893 sold 220,000 copies. In 1911, animal painting and nature photography brought a new level of illustrations. The work continued, eventually digitally, into the 21st century.

Since the end of the 19th century, encyclopaedias on specific countries or regions have also appeared. Geographical encyclopaedias should be distinguished from national encyclopaedias, which focus on their own country. Examples include the Deutsches Kolonial-Lexikon (1920), The Modern Encyclopaedia of Australia and New Zealand (1964), and the Magyar életrajzi lexikon (1967-1969). The last volume of the Great Soviet Encyclopaedia (1st edition) had dealt exclusively with the Soviet Union; it was published in 1950 as the two-volume Encyclopaedia of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in the GDR. The Fischer Weltalmanach (1959-2019) covers the countries of the world in alphabetical order, in currently held volumes per year.

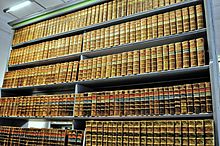

The largest encyclopedia ever printed in the German language had 242 volumes. The work, entitled Oeconomische Encyclopädie, was largely edited by Johann Georg Krünitz between 1773 and 1858. The University of Trier has completely digitized this work and made it available online.

See also: List of special encyclopaedias

The complete works of the Oeconomische Encyclopädie in the Upper Lusatian Library of Sciences and Humanities

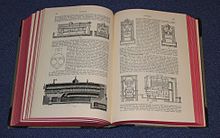

Opened volume of the encyclopaedia of all technology by Otto Lueger, 1904

Pauly's Real Encyclopedia of Classical Antiquities

Structure and order

Until the early modern period, encyclopaedias tended to have the character of non-fiction or textbooks. The distinction between encyclopaedias and dictionaries seems to be even more difficult. There is no sharp distinction between subject matter and words, for no language dictionary can do without factual explanations, and no subject dictionary like an encyclopedia can do without linguistic references.

The individual contributions to an encyclopedia are arranged either alphabetically or according to some other system. In the latter case, one often speaks of a "systematic" arrangement, although the alphabet can also be regarded as a system and therefore the term "non-alphabetical" would be more correct. Encyclopaedias arranged systematically may further be distinguished according to whether the division is of a more pragmatic or even arbitrary nature, or whether there is a philosophical system behind it. Instead of "systematic" one often uses the expression "thematic".

Systematic arrangement

→ Main article: List of systematics in encyclopedias

For the true scholar, the systematic arrangement alone is satisfactory, wrote Robert Collison, because it places closely related subjects side by side. He assumed that the encyclopedia would be read as a whole, or at least in large chunks. In nature, however, there are no compelling connections. Systems are arbitrary because they come about through a process of human reflection. Nevertheless, a systematic account has didactic value if it is logical and workable.

Pliny, for example, used many different principles of order. In geography, he begins with the familiar coastline of Europe and then progresses to more exotic parts of the world; he treated people before animals because people were more important; in zoology, he begins with the largest animals; in soul creatures, with those of the Indian Ocean because they were the most numerous. The first Roman tree treated of is the vine, because it is most useful. The artists appear in chronological order, precious stones according to their price.

Systematic arrangement was traditionally the norm until the 17th/18th centuries, when alphabetical arrangement became the norm. Nevertheless, even after that, there were individual major non-alphabetical works, such as the unfinished Culture of the Present (1905-1926), the French Bordas Encyclopédie of 1971, and the Eerste Nederlandse Systematisch Ingerichte Encyclopaedie (ENSIE, 1946-1960). In the original ten-volume ENSIE, individual named major contributions are listed according to thematic order. To search for an individual item, one must consult the index, which in turn is a kind of encyclopaedia in its own right.

After the encyclopedias were mostly arranged alphabetically, many authors still added a system of knowledge in the preface or introduction. The Encyclopaedia Britannica (like the Brockhaus in 1958) had an introductory volume called Propaedia since 1974. In it, the editor Mortimer Adler set out, by way of introduction, the merits of a thematic system. With it, he said, one could find an item even if one did not know its name. The volume broke down knowledge: first into ten major topics, and within those into a variety of sections. At the end of the sections, reference was made to corresponding specific articles. Later, however, the Encyclopaedia Britannica added two index volumes. In the case of the Propaedia, it is said that its main purpose is to show which topics are covered, while the index shows where they are covered.

In 1985, a survey of American academic libraries found that 77 percent found the new arrangement of Britannica less useful than the old one. One response commented that the Britannica came with a four-page manual. "Anything that needs that much explanation is too damn complicated."

Not encyclopedias per se, but nonetheless encyclopedic in nature, are nonfiction series in which many different topics are treated according to a uniform concept. One of the best known internationally is the French series Que sais-je ?, founded in 1941, with over three thousand titles. In Germany, C. H. Beck publishes the series C. H. Beck Wissen.

Alphabetical order

For a long time there were only a few texts in alphabetical order. In the Middle Ages, these were mainly glossaries, i.e. short collections of words, or lists such as of medicines. Glossaries were created from the 7th century onwards, by readers noting down difficult words on individual sheets of paper (according to initial letters) and then making a list out of them. The alphabetical order was usually followed only by the first or at most the third letter, and was not very consistent. Moreover, many words did not yet have a uniform spelling. Even in the 13th century, strict alphabetical order was still rare.

Some of the few early alphabetical encyclopedias mentioned include: De significatu verborum (2nd half of 2nd century) by Marcus Verrius Flaccus; Liber glossarum (8th century) by Ansileubus; and especially the Suda (c. 1000) from the Byzantine Empire. They are, however, more in the nature of linguistic dictionaries; significantly, the entries in the Suda are usually very brief and often deal with linguistic topics, such as idioms. After the alphabetical works of the 17th century, it was then above all the great French Encyclopédie (1751-1772) that definitively associated the term "encyclopaedia" with alphabetical arrangement.

Ulrich Johannes Schneider points out that encyclopedias previously followed the "university and academic culture of knowledge disposition through systematization and hierarchization". The alphabetical arrangement, however, has decoupled the encyclopaedias from this. It is fact-oriented and weights content neutrally. The alphabetical arrangement spread because it facilitated quick access. One such encyclopedia, the Grote Oosthoek, opined in its 1977 preface that it was a matter of utility, not scientific principle. Quick information from foreign subjects is obtained by a great wealth of keywords, thus saving time and energy. According to a 1985 survey, ready reference is the most important purpose of an encyclopedia, while systematic self-study was mentioned much less frequently.

It was easier for the editor if a larger work was divided thematically. A thematically delimited volume could easily be planned independently of others. With alphabetical arrangement, on the other hand, one must (at least theoretically) already know from the beginning how to distribute the contents among the volumes. One had to know all the lemmas (keywords) and agree on the cross-references.

Even those encyclopedists who advocated the systematic classification opted for the alphabetical arrangement for practical reasons. Among them was Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert of the great French Encyclopédie. A later editor and editor of that work, Charles-Joseph Panckoucke, again wanted to impose a thematic arrangement. But he merely distributed the articles among various subject areas, and within these subject areas the articles appeared in alphabetical order. This Encyclopédie méthodique par ordre des matières was thus a collection of 39 subject dictionaries.

Article length

Even within the alphabetically arranged works, there are still a number of different possibilities. Articles on individual topics, for example, can be long or short. The original Brockhaus encyclopaedia is a typical example of a short-article encyclopaedia, with many short articles describing a single subject. Cross-references to other articles or occasional summary articles provide context.

Long-article encyclopedias, on the other hand, contain large articles reminiscent of textbook-like treatises on relatively broad topics. An example is the part of the Encyclopaedia Britannica called Macropaedia in the 1970s to 1990s. Here it is not always clear to the reader in which major article to look for the subject he is interested in. As a reference work, such an encyclopaedia can therefore only be used well with an index, similar to a systematic arrangement.

The idea of using long, survey articles may have first come from Dennis de Coetlogon with his Universal history. It probably served as a model for the Encyclopaedia Britannica (which originally had some long articles, called treatises or dissertations). Longer articles were also a countermovement to the increasingly definitional and keyword-like encyclopaedia. However, long articles could not have been the result of a deliberate move away from the rather short dictionnaire articles. Sometimes they were the result of a weak editorial policy that did little to curb the authors' desire to write or simply copied texts.

| Longest articles in selected encyclopedias | |||

| Factory | Item name | Length in pages | Comments |

| Zedler (1732-1754) | "Wolfish Philosophy" | 175 | |

| Universal history (1745) | "Geography" | 113 | The work deliberately consisted of longer treatises. |

| Encyclopaedia Britannica (1768-1771). | "Surgery" | 238 | |

| Encyclopaedia Britannica (1776-1784). | "Medicine" | 309 | |

| Oeconomical Encyclopedia (1773-1858) | "Mill" | 1291 | The article covers the whole of volume 95 and most of volume 96, both published in 1804. |

| Ersch-Gruber (1818-1889) | "Greece" | 3668 | The article covers eight volumes. |

| Encyclopaedia Britannica (1974). | "United States" | 310 | Created by combining the articles on the individual constituent states. |

| Wikipedia in German (November 2020) | "Chronicle of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States." | 392 (PDF; 1,564,136 Bytes) | |

Internal resources

For the practical use of an encyclopedia, various tools have been developed over time. Even in ancient times, it was common to divide a long text into chapters. Corresponding tables of contents, on the other hand, are a relatively late development. They arose from titles of works. Before the 12th century, they were still very rare and only became common in the 13th century.

Thus the Naturalis historia has a summarium, an overview, written by Pliny. In some manuscripts, the summarium is found undivided at the beginning, sometimes divided into the individual books, as was probably most practical in the age of scrolls. Sometimes the text is found both at the beginning and again later before the individual books. How Pliny himself handled it is impossible to determine today. While Pliny described the contents of the work in prose, some later printed editions turned it into a table, similar to a modern table of contents. In doing so, they were quite free with the text and adapted it to the presumed needs of the readers.

| Print from 1480 (Beroaldo) | Budé edition from 1950 |

| The twenty-sixth book contains remaining | BOOK 26 INCLUDES |

Indexes, i.e. registers of keywords, also appeared in the 13th century and spread rapidly. In an encyclopaedia, Antonio Zara had first used a kind of index in his Anatomia ingeniorum et scientiarum (1614); truly suitable indices did not appear in encyclopaedias until the 19th century.

One of the first works with cross-references was the Fons memorabilium by Domenico Bandini (ca. 1440). By the 18th century at the latest, they became common. In the 20th century, some encyclopaedias, following the example of the Brockhaus, switched to using an arrow symbol for the reference. In the digital age, hyperlinks are used.

Content balance

A frequently recurring theme in research is the balance between subject areas in an encyclopedia. This balance or equilibrium is lacking, for example, if history or biography are given a lot of space in a work, while natural sciences and technology are given much less. In a subject encyclopedia, the lack of balance is criticized when, for example, political history is treated in much greater detail than social history in a work on ancient history.

Sometimes the criticism is of individual articles, measuring which lemma has received more space than another. Harvey Einbinder found noteworthy about the 1963 Encyclopaedia Britannica, for example, the article on William Benton. This American politician, according to the encyclopedia, has become "a champion of liberty for the whole world" in the Senate. The article is longer than the one on former Vice President Richard Nixon; as Einbinder speculates, because Benton was also editor of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Einbinder also criticized the fact that while the "Music" article highly praised Béla Bartok and Heinrich Schütz, these composers were not given their own articles.

Even pre-modern encyclopedias usually had a universal claim. Nevertheless, the interests or the abilities of the author often brought with them a limitation. The Naturalis historia, for example, included treatises on ethnology and art, but the focus was on areas of knowledge that today are classified as natural sciences. In the 18th century, universal encyclopaedias began to break down the opposition between more humanistic and more scientific works. In some cases, a work could still be seen to have its origins, or the editor made a conscious decision to raise its profile by focusing on a particular field or approach: Ersch-Gruber followed the historical approach, because of its descriptiveness, while Meyer preferred the natural scientific.

The question of balance is not least of importance in works for which the reader has to pay. He is likely to be dissatisfied if, in his opinion, a universal encyclopedia leaves too much space to such topics as are of little interest to him personally, but which he helps to pay for. Robert Collison points out the irony that readers wanted the most complete outlines possible and "unquestioningly paid for millions of words they probably never read," while the encyclopedia makers also strove for completeness and wrote entries on minor topics that hardly anyone reads.

However, balance is still debated even in the case of freely accessible encyclopedias such as Wikipedia. For example, there is the question of whether it does not say something about the seriousness of the work as a whole if pop culture topics are (allegedly or actually) represented above average. At the very least, as historian Roy Rosenzweig pointed out, the balance is strongly dependent on which part of the world and which social class the authors come from.

Information in traditional encyclopedias can be evaluated by measures related to a quality dimension such as authority, completeness, format, objectivity, style, timeliness, and uniqueness.

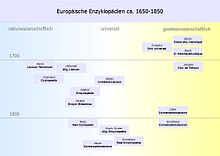

Some important encyclopaedias of Europe according to their position between more scientific and more humanistic contents

The internationally best-known modern encyclopaedia in print: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1990s. The first volume, with a green stripe, is the systematic Propaedia ("Outline of Knowledge") with its references to Micropaedia and Macropaedia. Then follows, with red stripes, the Micropaedia ("Ready Reference"), a classic short-article encyclopedia with about 65,000 articles. The Macropaedia ("Knowledge in Depth"), lower board, covers major topics in about seven hundred articles. Finally, behind the Macropaedia, with blue stripes, is the two-volume alphabetical index with references to Micropaedia and Macropaedia.

Tree of knowledge in the Encyclopédie, 18th century, based on Francis Bacon. The human faculties were assigned subject areas: history to memory, philosophy to reason (including the natural sciences), poetry to imagination.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is an encyclopedia?

A: An encyclopedia is a collection of information, usually in the form of a book. It can also be on CDs or online.

Q: What is the largest encyclopedia in the English language?

A: The largest encyclopedia in the English language is English Wikipedia, which has more than 6 million articles.

Q: How long have encyclopedias been around for?

A: Book series that summarize all knowledge have been published for thousands of years. A famous early one was the Natural History by Pliny the Elder and the word "encyclopedia" was first used in the 16th century.

Q: Who wrote the French Encyclopédie?

A: The French Encyclopédie was written by Denis Diderot and had major parts written by many people from all around the world.

Q: How did encyclopedias become popular after printing press invention?

A: After printing press invention, dictionaries with long definitions began to be called encyclopedias that were books that has articles or subjects For example, a dictionary of science, if it included essays or paragraphs, it was thought of as an encyclopedia or knowledgeable book on the subject of science. Some encyclopedias then put essays on more than one subject in alphabetical order instead of grouping them together by subject. The word "encyclopedia" was put in title some encyclopedias and companies such as Britannica were started for purpose publishing these books for sale to individuals and public use libraries.

Q: How are internet encyclopedias different from printed ones?

A: Internet encyclopedias allow their paying customers to submit articles from other encyclopedias while printed ones hire hundreds of experts to write articles and read and choose articles.

Search within the encyclopedia