Edvard Munch

Edvard Munch [![]()

![]() ɛdvɒ:rt muŋk] (b. 12 December 1863 in Løten, Hedmark, Norway; † 23 January 1944 at Ekely in Oslo) was a Norwegian painter and graphic artist. In addition to over 1700 paintings (see the list of paintings by Edvard Munch), he produced numerous prints and drawings. Munch is considered a trailblazer for the expressionist direction in modernist painting. His first exhibition in Germany caused a scandal ("Munch case"). Subsequently, he enjoyed an early reputation in Central Europe as an epoch-making new creator. Today, his idiosyncrasy and status are also recognized in the rest of Europe and the world.

ɛdvɒ:rt muŋk] (b. 12 December 1863 in Løten, Hedmark, Norway; † 23 January 1944 at Ekely in Oslo) was a Norwegian painter and graphic artist. In addition to over 1700 paintings (see the list of paintings by Edvard Munch), he produced numerous prints and drawings. Munch is considered a trailblazer for the expressionist direction in modernist painting. His first exhibition in Germany caused a scandal ("Munch case"). Subsequently, he enjoyed an early reputation in Central Europe as an epoch-making new creator. Today, his idiosyncrasy and status are also recognized in the rest of Europe and the world.

Munch's paintings focus on the human being and his essential emotional experiences, from love to grief and death. In them, Munch primarily processed autobiographical experiences and adventures. The artist painted important motifs over and over again in different versions, including many of his major works grouped together in the so-called Life Frieze, among them The Scream, Madonna, Vampire, Melancholy, Death in the Sickroom or The Dance of Life.

Life

Origin

Edvard Munch grew up in the Norwegian capital Oslo, which at that time was called Christiania (from 1877 Kristiania). His father Christian Munch was a deeply religious military doctor with a modest income. The historian Peter Andreas Munch was Edvard Munch's uncle.

Munch's father Christian married the twenty years younger merchant's daughter Laura Catherine Bjølstad at the age of 44. The young wife gave birth to their son Edvard at 27 and died of tuberculosis at 33, when Edvard was five years old. Edvard himself was of frail health, but it was not he but his elder sister Sophie who was the next victim of consumption. His younger sister Laura was under medical treatment for "melancholia" (by today's classification most likely depression). Posthumously, medical experts also hypothesized a borderline personality disorder (emotionally unstable personality disorder) with regard to Edvard Munch, partly in connection with a bipolar disorder (manic-depressive illness). Of the five siblings (Edvard included), only his brother Andreas married, but died only a few months after the wedding.

The parental home was culturally stimulating - but it was the impressions of illness, death and mourning to which Munch mainly returned in his art.

Realism

At his father's request, Munch went through a year at technical school and then, supported by his aunt Karen, turned to art with great seriousness. He studied the Old Masters, followed lessons in nude drawing at the Royal Drawing School, and for a time received correction from Norway's leading naturalist, Christian Krohg. His early work was marked by a French-inspired realism, and he soon stood out as a great talent.

In 1885 Munch was in Paris during a short study visit. In the same year he began work on his decisive work The Sick Child. Here he broke radically with realism, in which Christian Krohg, for example, had painted a similar motif five years earlier. Munch worked on the painting for a long time in search of a first impression and a valid painterly expression for a painful personal experience, the death of his sister Sophie. He dispensed with space and plastic form and advanced to an iconic composition. The coarse materiality of the surface showed traces of the laborious creative process. The criticism was very negative. Nevertheless, Munch took up this motif again and again throughout his life.

The major works of the following years are less provocative in form. Inger on the Beach from 1889 testifies to Munch's capacity for lyrical mood depiction in keeping with the neo-Romantic current of the time. He painted this picture in Åsgårdstrand, a small coastal town near Horten. The winding coastline, so characteristic of this area, is a leitmotif in many of Munch's compositions.

Kristiania-Bohème

In 1889 Munch also painted a portrait of the head of Kristiania's bohemian scene, Hans Jæger. Munch's interaction with Jæger and his circle of radical anarchists in the second half of the 1880s became a decisive turning point in his life and the source of an inner ferment and conflict. It was at this time that he began his extensive biographical-literary production, which he continued to record at various stages of his life. These early notes functioned as a "reference work" on several of the central motifs from the 1890s. In keeping with Jæger's ideas, he wanted to convey truthful "close-ups" of the longings and agonies of modern life-he wanted to "paint his life."

France

In the autumn of 1889 Munch had a major solo exhibition in Kristiania, after which the state granted him an artist's grant for three consecutive years. Paris was the natural destination, where he was for a short time - together with his friend Kalle Løchen - a pupil of Léon Bonnat. The more important impulses, however, he received by orienting himself to the artistic life of the city. It was here that a Post-Impressionist breakthrough took place at the time, with various anti-naturalist experiments that had a liberating effect on Munch.

Shortly after Munch arrived in France that first autumn, news reached him of his father's death. The loneliness and melancholy in his painting Night in Saint-Cloud (1890) are often seen against this background. The dark interior with the solitary figure at the window is entirely dominated by blue tones - a valeur painting that recalls Whistler's nocturnal colour chords, but also captures in a distinct, modern way the "decadence" of the last decade of the 19th century.

At the autumn exhibition in Kristiania in 1891, Munch showed Melancholy, among other works. Here large, curved lines and more homogeneous areas of color dominate - a simplification and stylization of the motif related to Paul Gauguin and French synthetists. "Symbolism - nature is formed by a mood of the mind," Munch wrote about it.

At this time he made the first sketches for his most famous work, The Scream. He also painted a series of pictures in an impressionistic and almost pointillist style, with motifs of the Seine, Parisian streetscapes and Kristiania's Karl Johans gate paradise street. However, Munch's main interest was in impressions of the soul rather than the eye.

·

Spring at Karl Johans gate (1890)

· .jpg)

Rue Lafayette (1891)

·

Melancholy (1892)

·

Despair (1892)

·

The Scream (1893)

Germany

→ Main article: Munch case

In the autumn of 1892, Munch presented the results of his visits to France in Kristiania. The Norwegian landscape painter Adelsteen Normann saw this exhibition and helped the then still unknown Munch to an invitation from the Berlin Kunstverein. Munch's first exhibition in Berlin took place in the "Architektenhaus" at Wilhelmstraße 92. It opened with 55 paintings on 5 November 1892 and ended with a great scandal. The public and the older painters took Munch's pictures as an anarchistic provocation, and the exhibition was closed in protest as early as 12 November 1892 at the instigation of Anton von Werner, the director of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts.

As a result, Munch's name suddenly became known in Berlin and he decided to stay in the city. He came into a circle of literati, artists and intellectuals in which Scandinavians were strongly represented. The circle included the Swedish playwright August Strindberg, the Polish poet Stanisław Przybyszewski, the Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland, the Danish writer Holger Drachmann, and the German art historian Julius Meier-Graefe. They met at the Gasthaus Zum schwarzen Ferkel Unter den Linden/corner of Neue Wilhelmstraße and discussed Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy, occultism, psychology, and the dark side of sexuality.

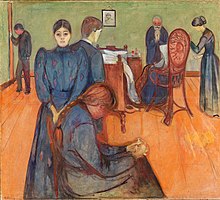

In December 1893, Munch exhibited at Unter den Linden and showed, among other things, six paintings under the heading Study for a Series: Love. This was the beginning of what later developed into the Life Frieze, "a poem about life, love, death". This cycle of paintings includes motifs saturated with atmosphere, such as The Storm, Moonlight and Starry Night, where one can sense an influence from the Swiss-German Arnold Böcklin. Other motifs such as Rose and Amalie or Vampire illuminate the night side of love. Several paintings have death as their theme, and the one that attracted the most attention was Death in the Sick Room, a composition that particularly shows the influences of French Synthetism and Symbolism. In garish yet pale colours, the painting depicts a frozen scene, comparable to a tragic final tableau in an Ibsen play. This motif also goes back to the memory of the death of his sister Sophie and shows Munch's entire family. The dying woman, seated in a chair, turns her back on the viewer, but is brought into view by the figure Munch himself depicts. The following year, Munch expanded the frieze to include motifs such as Fear, Ashes, Madonna, and Sphinx (The Woman in Three Stages). The latter is a monumental motif entirely in the spirit of Symbolism.

Together with Meier-Graefe, Przybyszewski and others published the first book on Munch's art in 1894. He characterized it as "psychic realism".

· .jpg)

The Tempest (1893)

·

Starry Night (1893)

· ,_Gothenburg_Museum_of_Art.jpg)

Vampire (1893)

·

Fear (1894)

· .jpg)

Ashes (1895)

· .jpg)

Madonna (1894/95)

Back in France 1896

Munch left Berlin in 1896 and settled in Paris, where Strindberg and Meier-Graefe, among others, were staying. Here he devoted more and more attention to graphic means. In Berlin he had already begun with etching and lithography, and now, in collaboration with the famous printer Auguste Clot, he created exquisite color lithographs and his first woodcuts. Munch also planned to publish a portfolio entitled "The Mirror", a graphic "frieze". Thanks to his mastery of means and his great artistic originality, Munch enjoys in our time the reputation of a classic of graphic art.

In Paris he also produced programme posters for two Ibsen performances at the Théâtre de L'Œuvre, while the commission to illustrate Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal remained in its infancy.

The turn of the century

Returning to Norway in 1898, Munch created the illustrations for a special edition of the German magazine Quickborn to texts by August Strindberg.

Around the turn of the century, Munch attempted to complete the frieze. He painted a series of new pictures, some in larger format and partly influenced by the Art Nouveau aesthetic. For the large painting Metabolism/Metabolism (1898) he produced a wooden frame with carved reliefs. It was initially given the title Adam and Eve, revealing the central place that the Fall myth occupied in Munch's pessimistic philosophy of love. Motifs such as The Empty Cross and Golgotha (both c. 1900) reflect a metaphysical orientation in Munch's own time and also echo Munch's childhood and youth in a Pietist milieu.

A gruelling love affair with Tulla Larssen at that time encouraged Munch to experience art as a vocation.

The period around the turn of the century was one of restless experimentation. A colorful and decorative style manifested itself, influenced by the art of the Nabis and especially by a Maurice Denis. In 1899 Munch painted The Dance of Life, which can be understood as a bold and personal monumentalization of this decorative surface style.

A series of landscape paintings have the Kristiania fjord as their subject. These decorative and sensitive nature studies are considered highlights of Nordic symbolism. The classic atmospheric painting The Girls on the Bridge was painted in Åsgårdstrand in the summer of 1901.

·

Metabolism (1898/99)

· .jpg)

Golgotha (1900)

· .jpg)

The Dance of Life (1899/1900)

·

The Girls on the Bridge (1901)

Success and crisis

At the beginning of the new century Munch's career as an artist took another upswing. In 1902 he showed the whole frieze for the first time at the Berlin Secession exhibition. A Munch exhibition in Prague became important for several Czech artists. Portraits, often in full figure, gradually became an important part of his work. The group portrait The Four Sons of Dr. Max Linde (1903, Museum Behnhaus, Lübeck) is considered a major work of modern portrait painting. He often sought recreation in Travemünde at this time and donated the painting of the same name to the Behnhaus out of attachment.

The Fauvists, with Matisse at their head, shared with Munch many of his artistic aspirations. The Brücke group of artists in Dresden showed interest in Munch, but failed to attract him to their exhibitions.

The artistic success was accompanied by conflicts on a personal level. Alcohol had become a problem and Munch was psychologically unbalanced. He tormented himself with memories of his tragic love story. His relationship with Tulla had ended in 1902 with a revolver scene in which Munch's left hand had been shot. Although he was never to get over the disgrace, during these years it became an obsession. Tulla's traits can be traced, among others, in Marat's Death (two versions from 1907), a motif that can more generally be said to depict "the struggle between man and woman that can be called love".

Henrik Ibsen died in May 1906, and in the autumn Munch produced set designs for Max Reinhardt's performance of Ghosts in the small hall of the Deutsches Theater Berlin. For the foyer of the theatre he also created a new version of his life friezem the Reinhardt Frieze, which can be seen today in the Berlin National Gallery. Since then, Ibsen has occupied an ever larger space in Munch's consciousness: the Self-Portrait with Wine Bottle of 1906 shows a powerless, slumped figure sitting alone at a table in a claustrophobic café; a tragic apparition, closely related in spirit to Oswald in Ibsen's drama.

Munch executed a monumental fantasy portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche on commission, and during several visits to Weimar he painted a portrait of the late philosopher's sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche. The Nietzsche portrait was the only portrait Munch created from a photograph rather than a living model. During this period Munch also painted portraits of Harry Graf Kessler and Henry van de Velde.

Between 1902 and 1908 Munch spent most of his time in Germany. Painting commissions took him several times to Berlin, Lübeck (1903), Weimar (1904) and Chemnitz (1905). Afterwards Thuringia with Elgersburg, Weimar, Ilmenau and Bad Kösen (1905/1906) and finally Warnemünde (1907/1908) became his permanent domiciles. Warnemünde was to be the last station of the self-chosen German exile and offered the artist for a short time the sought-after physical and mental recreation.

New motifs testify to a more extraverted orientation. Bathing Men (1907/1908) pays lively homage to vital masculinity. Alcohol and nervous problems nevertheless reached a critical point, and Munch decided to spend eight months in a Copenhagen mental hospital under the care of Daniel Jacobson. In Norway, his artistic achievement was finally recognized, and while he was in the clinic, he was awarded the Norwegian Order of Saint Olav.

·

The Four Sons of Dr. Max Linde (1903)

·

Marat's Death I (1907)

·

Friedrich Nietzsche (1906)

· .jpg)

Bathing men (1907)

·

Self-portrait in the clinic (1909)

Back in Norway

Munch lived in Norway from 1909 until the end of his life. He first settled in Kragerø, a coastal town in the south of the country. Here he painted, among other things, several classical winter landscapes and threw himself with zeal into the competition for the decoration of the new ballroom of Oslo University, the Aula.

In 1912, at the great Sonderbund exhibition in Cologne, Munch was given a prominent place among the pioneers of modern art.

In Kragerø he had spacious outdoor studios built, where he worked for several years on the designs for the university auditorium. After protracted disputes, Munch was finally accepted and his work mounted on site in 1916.

In Munch's own words, the motifs pay homage to "the eternal forces of life". The background motif, called The Sun, is a sunrise over the fjord, inspired by the view Munch had from his property rented in Kragerø. At the same time, he used the symbolic potential of light here. Counterparts in the auditorium are the large canvases The Story and Alma Mater. Under a mighty oak tree in a barren, rugged landscape, an old man sits and tells a young boy the saga of the people. In a wild, lush landscape, a woman sits on a beach with an infant while older children explore nature. Apart from the fact that the two "archetypal" motifs allude to humanities and natural science, they are expressions of the masculine and feminine principle, which is a central opposition in Munch's imagery.

Munch devoted himself to the emerging workers' movement in several motifs from that period, some in monumental form. The painting Workers on their Way Home (1913-15) is, moreover, a dynamic study in perspective and movement. In 1916 Munch acquired the Ekely estate near Kristiania. Landscape, people in harmony with nature, ploughing horses are motifs now depicted in clear, strong colours. A fresh, spontaneous brushwork gives the impression of a sensual homage to sun, air and earth.

At Ekely, Munch lived in increasingly self-imposed isolation, spartan, surrounded only by his paintings. He was exceedingly productive. Although he was reluctant to part with "his children", the paintings were lent to a number of exhibitions at home and abroad.

In later years Munch often painted studies and compositions from models. Among them there are some that are more lively and life-affirming than earlier works. And yet even now he was devoted to exploring the conflicted themes of the 1890s. His graphic production continued to be considerable, including a series of lithographic portraits. Edvard Munch died in January 1944.

·

The Sun (1911)

·

The Story (1911, 1914-16)

· ![]()

Alma Mater (1916)

·

Workers on their way home (1913/14)

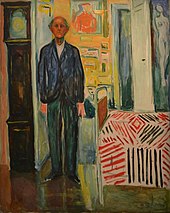

Self-portrait between clock and bed (1940-43)

Munch 1933, photograph by Anders Beer Wilse

Self-portrait with wine bottle (1906)

Munch's house (today museum) in Åsgårdstrand

Edvard Munch in 1902 in the garden of the Linde Villa in Lübeck. In the background The Iron Age by Auguste Rodin.

Death in the Sick Room (1893)

,_NG.M.01111.jpg)

Night at Saint-Cloud (1890)

Hans Jæger (1889)

The Sick Child (1885/86)

.jpg)

Self-portrait (1882)

Pilestredet 30 in Oslo. From 1868 to 1873 the Munch family lived in house 30A, later until 1875 in 30B (in the foreground).

Factory

Style and painting style

Munch is counted - often in connection with van Gogh, Gauguin, Ensor or Hodler - among the "early expressionists", the forerunners of Fauvism and Expressionism. What they have in common is an "expressive art" and the great colorfulness of their works, but also their solitary nature. With little or no academic training and no subsequent pupils, their work reveals a strong subjectivity and reference to their own biographies. Thus, all the artists mentioned have also created significant self-portraits.

Munch's early works were still in the tradition of Norwegian naturalism and realism. In Paris he became acquainted with Pointillism and Synthetism. However, his painterly temperament and the permissiveness of his technique remained largely unaffected by these styles. According to Tone Skedsmo, Munch merely experimented with the technical possibilities offered by Impressionism, for example, and rejected everything that did not lead him further in his search for a form of expression that suited him. Even when new avant-garde styles emerged in the 20th century with Cubism, Futurism, and Constructivism, Munch adhered to representational, figurative painting in his later work and consciously distanced himself from the "modern style" of abstract painting.

Munch painted from the arm with great impulsiveness. He often literally fought with the canvas, attacked it like an adversary, scratched, scraped, stabbed and cut, worked with overpaintings and transparent permeability. He also did not shy away from incorporating the elements of nature, which he called a "horse cure," in order to force natural decay - at the risk of completely destroying the works. Munch's contemporary, Rolf Stenersen, described one such encounter: 'It happened that Munch simply fought with the paintings, attacking them furiously, tearing them up and kicking them. 'The damned painting is getting on my nerves, now it's been through one horse-cure after another and is only getting worse. Please be good enough to carry it up to the floor, just throw it in as far as you can.'"

Reference to personal experience

According to Arne Eggum, Munch placed man and his attitude to life at the centre of his art. In doing so, he drew on his own experiences and traumatic experiences and transformed them into archetypal images that were composed of his private symbolism. Expressionism, as Munch understood it, was thus "an extremely subjective art while retaining something primal and primitive." Where Gauguin, for example, explored the primitive in human nature in Tahiti, Munch found "his own Tahiti within himself." Munch thus took up positions of subjectivism that were reflected in Scandinavia at his time in the literary works of Ibsen and Strindberg as well as in the philosophy of Kierkegaard.

Munch did not strive for a copy of nature, but for a symbol of his state of mind. He described himself: "I do not paint after nature - I take my motifs from it - or draw from its abundance. I do not paint what I see, but what I saw. The camera cannot compete with the brush and palette - so long as it cannot be used in hell or heaven." In this, Munch deliberately included the "hell" of his own traumatic experiences. Of his unstable condition, both physically and psychologically, he wrote: "I don't want to reject my illness, because my art owes it much." Art itself was like a disease for him: "Painting is a disease for me, an intoxication. A sickness I don't want to get rid of. An intoxication that I need."

Art offered Munch the opportunity to come to terms with himself, but also to communicate his experiences to other people: "Through my art I tried to explain life and its meaning to myself. In doing so, I also wanted to help others come to terms with life." Elsewhere he wrote: "My art had its root in reflection, in which I sought to explain this disproportion to life - Why wasn't I like the others? Why born - something I had not asked for. The curse and the reflection on it became the undertone in my art. Its strongest undertone, and without it my art would be a different one - But in the reflection on it and in the release of it in my art there was an urge and a desire for my art to bring me light - darkness and also light for people."

Life frieze and picture cycles

Munch compiled his most important works of the early creative period - pictures such as The Scream, Madonna, Vampire, Melancholy, Death in the Sickroom or The Dance of Life - in the so-called Life Frieze. He named the central themes: "The frieze is a poetry about life, love and death." Munch's art was often called "literary," especially in France. The painter himself rejected this term, which he understood as an accusation, just as he defended himself against the derogatory label "thought painting." However, he also always defended himself against a purely decorative art and drew a comparison with Cézanne, for example: "I painted a still life just like Cézanne, only that I painted a murderess and her victim in the background." Elsewhere, he compared himself to da Vinci: "Just as Leonardo da Vinci studied the inside of the human body and dissected corpses - so I try to dissect the soul." Whereas in da Vinci's day the autopsy of corpses was punishable by law, in Munch's present "it is the psychic phenomena that are almost considered immoral and frivolous to dissect."

The Life Frieze took up the idea of a picture cycle also pursued by other contemporary artists such as Van Gogh, Klinger or Klimt. However, it was also Munch's attempt to create an overall artistic conception of "the modern life of the soul", as he put it, from the individual aspects of his art, thereby transcending his personal memory work and achieving artistic autonomy. In his later work, too, he held on to the idea of a picture cycle and created as commissioned works the Linde Frieze (1904 for Max Linde), the Reinhardt Frieze (1907 for Max Reinhardt), the Freia Frieze (1922 for the Freia chocolate factory) as well as the decoration of the auditorium of the University of Kristiania, unveiled in 1916, with its central head painting The Sun.

Seriality, graphics and photography

Together with Monet, Munch is also a founder of serial art. Monet was concerned here with the external impression of a motif, which he captured in different representations, Munch with the recurring implementation of some very basic memories and experiences. Munch realized many of his central pictorial motifs in several paintings or prints; he often wrestled for many years with one and the same motif, for which he always sought new, more valid representations. His ultimate failure in the final completion of a motif points ahead to a paradigm of modern art: the abandonment of the ideal of a valid one-off.

An important step towards seriality was Munch's preoccupation with graphic art, which began in 1894 and gained new popularity in France during this decade. It soon took an important place in Munch's oeuvre alongside painting. Munch tried his hand at a wide variety of techniques, from drypoint etching to lithography and woodcut. His handling of the new medium resembled that of canvas: he worked intensively on the printing plates, altered them again and again, added new elements, sanded down other parts, and colored the prints by hand in different variations. According to Hans Dieter Huber, Munch treated the printing plate "like a kind of sketch paper" and, as in his paintings and notebooks, was always looking for new ways of expressing the same motif.

·

The Sick Child (drypoint, 1894)

·

The Scream (lithograph, 1895)

· _G0192-59_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Self-portrait with skeleton arm (lithograph, 1895)

· .jpg)

Madonna (Lithograph, 1895)

·

Evening. Melancholy I. (Woodcut, 1896)

Experimentation with an uncertain outcome was an artistic concept of Munch's, not only in his painting and graphic works. According to Dieter Buchhart, he also regularly crossed the conventional boundaries between artistic techniques, be it painting, graphics, drawing, photography or film. In 1902, Munch acquired his first camera and also explored pictorial problems in the new technique, such as the interaction of several image layers and the design of forms, shadows, and empty spaces. The subject of his photographs was often himself, so that the works that were never exhibited during Munch's lifetime are now presented as an early artistic form of selfies.

·

Self-portrait in Warnemünde (1907)

·

Self-portrait in Warnemünde (1907)

·

Self-portrait à la Marat (1908)

·

Self-portrait in Ekely (1930)

.jpg)

Auditorium of the University of Oslo

Self Portrait in Hell (1903)

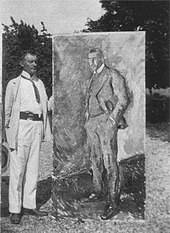

Edvard Munch with the portrait of Jappe Nilssen, 1909, painting by Aksel Waldemar Johannessen

Questions and Answers

Q: Who was Edvard Munch?

A: Edvard Munch was a Norwegian painter and print-maker born in Adalsbruk.

Q: How many known paintings did Edvard Munch paint?

A: Edvard Munch painted 1789 known paintings.

Q: What is Edvard Munch known for?

A: Edvard Munch is known for his treatment of emotion, particularly fear, and his influence on expressionism in the 20th century.

Q: Did Edvard Munch have success as a painter during his life?

A: Yes, Edvard Munch had success as a painter during his life, becoming famous outside Norway and having his paintings sell for high prices.

Q: Did the National Gallery (Norway) purchase paintings by Edvard Munch?

A: Yes, the National Gallery (Norway) used much money to buy paintings by Edvard Munch.

Q: Where did Edvard Munch paint a large murals?

A: Edvard Munch painted a large mural in the aula (main room) of Norway's (then) only university.

Q: What was the style of painting that Edvard Munch is associated with?

A: Edvard Munch is associated with expressionism.

Search within the encyclopedia