Eastern Front (World War II)

![]()

This article deals with the German-Soviet War. The war plan itself deals with Unternehmen Barbarossa.

Significant military operations during the German-Soviet War

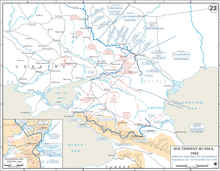

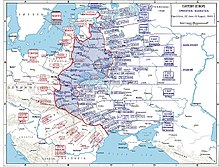

1941: Białystok-Minsk - Dubno-Luzk-Rivne - Smolensk - Uman - Kiev - Odessa - Leningrad Blockade - Vyazma-Bryansk - Kharkov - Rostov - Moscow - Tula1942

: Rzhev - Kharkov - Operation Blue - Operation Brunswick - Operation Edelweiss - Stalingrad - Operation Mars1943

: Voronezh-Kharkov - Operation Iskra - Northern Caucasus - Kharkov - Enterprise Citadel - Oryol - Donets-Mius - Donbass - Belgorod-Kharkov - Smolensk - Dnepr1944

: Dnepr-Carpathians - Leningrad-Novgorod - Crimea - Vyborg-Petrosavodsk - Operation Bagration - Lviv-Sandomierz - Yassy-Kishinev - Belgrade - Petsamo-Kirkenes - Baltic States - Carpathians - Hungary1945

: Courland - Vistula-Oder - East Prussia - West Carpathians - Lower Silesia - East Pomerania - Lake Balaton - Upper Silesia - Vienna - Oder - Berlin - Prague

The German-Soviet War was a part of the Second World War. In the former German Empire it was called the Russian or Eastern Campaign, in the former Soviet Union, in present-day Russia and some other successor states of the Soviet Union it was called the Great Patriotic War (Russian Великая Отечественная война Velikaya Otetschestvennaya woina). From 1941 to 1945, the Eastern Front formed the main land front of the Allies in the fight against the Nazi German Reich and its allies. The war began on June 22, 1941, with the invasion of the Soviet Union by the German Wehrmacht, and ended with the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht on May 8-9, 1945, after the end of the Battle of Berlin on May 2, 1945. The surrender of the German Wehrmacht is honored in many countries as Liberation Day.

Adolf Hitler announced his decision to launch this war of aggression to the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) on July 31, 1940, and on December 18, 1940, he ordered military preparations to be made for it by May 1941 under the code name "Unternehmen Barbarossa." This was a deliberate attempt to break the German-Soviet non-aggression pact concluded on August 24, 1939. In order to conquer "living space in the East" for the "Aryan master race" and to destroy "Jewish Bolshevism", large parts of the Soviet population were to be expelled, enslaved and killed. The Nazi regime deliberately accepted the death by starvation of millions of Soviet prisoners of war and civilians, had Soviet officers and commissars murdered on the basis of orders contrary to international law, and used this war for what was then called the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question."

After initial German successes, Soviet victories in the Battle of Moscow in late 1941 and especially in the Battle of Stalingrad in 1942/43 ushered in Germany's complete defeat. After the German "Unternehmen Zitadelle" failed in the summer of 1943, the initiative finally passed to the Red Army. After the collapse of Army Group Center in the summer of 1944, which followed the opening of the long-awaited "Second Front" in Western Europe by the Western Allies of the anti-Hitler coalition, the Wehrmacht was militarily defeated and could only offer stalling resistance. Nevertheless, the final months of the war were still marked by extremely heavy casualty fighting.

Primarily because of the mass crimes planned and executed by Germans against the civilian population, between 24 and 40 million inhabitants of the Soviet Union died in the course of the war. This war is generally considered the "most monstrous war of conquest, enslavement and extermination known to modern history" because of its criminal objectives, warfare and results.

Previous story

See also: Prehistory of the Second World War in Europe

National Socialist goals

→ Main article: Hitler's "Eastern Program

The German-Soviet War can be traced back essentially to the ideological-political goals of National Socialism, which saw itself as a radical ideological antithesis to Bolshevism. In his programmatic pamphlet Mein Kampf (1925), Hitler regarded Bolshevism as a tyranny of an alleged "world Jewry" aimed at world conquest. Its annihilation and the subjugation of the allegedly dependent, "racially inferior" Slavs were inevitable in order to provide the German "Aryans" with the "living space in the East" to which they were entitled. To conquer this was a main goal of Nazi foreign policy.

The intended conquest of large parts of Eastern Europe was indeed linked to older goals of the traditionally anti-communist military elites of the Kaiserreich and the Weimar Republic; the necessary rearmament, the breaking of the Treaty of Versailles and the withdrawal from the League of Nations were also largely consensual in the Reichswehr already around 1930. The German military, however, was essentially concerned with revising the results of the First World War. However, the Lebensraum policy of the Nazi leadership, based on pure racism, and its intention to destroy the Soviet Union as a state and at the same time its actual or presumed elites, went far beyond these earlier goals.

Hitler's foreign policy from 1933 initially put his long-term goal of conquest on the back burner. However, his speech to the highest representatives of the Reichswehr on February 3, 1933, already hinted at it (see Liebmann recording). He later emphasized it again and again to the Wehrmacht leadership, for example during the Sudeten crisis. The Nazi regime's goals of mass extermination and Germanization became apparent during the invasion of Poland, in which specially established Einsatzgruppen carried out massacres of members of the ruling elite and of Jews, some of which had been coordinated with the Wehrmacht leadership. These specifically Nazi extermination goals were to achieve a determining, "never-before-seen dimension" for the planning and conduct of the war against the Soviet Union, which distinguished it from all previous wars, including those of the Nazi regime.

According to Hans-Erich Volkmann, Hitler was also concerned with the achievement of world domination for which he needed the Soviet raw materials as a foundation for a self-sufficient and unassailable Europe. On September 17/18, 1941, Hitler expressed this during a conversation at the Führer's headquarters:

"The struggle for hegemony in the world is decided for Europe by the possession of Russian space; it makes Europe the most blockade-proof place in the world."

German-Soviet relations from 1939

In the "Great Terror" of 1936 to 1938, Soviet dictator Josef Stalin had thousands of war-experienced Soviet generals and officers murdered, greatly weakening the Red Army. Since the Munich Agreement of October 1938, he had been convinced that the Western powers would not offer any significant resistance to Nazi Germany and were trying to pressure the Soviet Union into a war that they themselves did not want to fight. As a result, he made a turn in Soviet foreign policy and sought a reconciliation of interests with the German Reich.

The Nazi regime was willing to acknowledge Soviet expansionist interests in Eastern Europe in order to "push Britain off the Continent," to be able to "wage the invasion of Poland as a war on a single front," and to "have room on its back for the later turn to the West," "which in turn was envisaged as a pre-switch event of the Lebensraum War."

With a credit agreement of August 20, 1939, both states agreed on Soviet deliveries of food and raw materials to Germany in exchange for German industrial and armaments goods to the Soviet Union. This was followed on August 23, 1939, by the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact ("Hitler-Stalin Pact") with a secret additional protocol in which the contracting parties delimited their mutual spheres of interest in Eastern Europe. The central point of the protocol provided for the fourth partition of Poland and assigned Estonia, Latvia, Finland, eastern Poland and Romanian Bessarabia to the Soviet sphere of interest.

On September 1, 1939, the German invasion of Poland triggered World War II. For its part, the Soviet Union occupied eastern Poland and later Lithuania from September 17, 1939, in accordance with the secret additional protocol, for which it exchanged parts of Poland to the German occupiers. In addition, at the end of September 1939, it concluded a border and friendship treaty with Germany, which was to regulate the final course of its borders.

In the following months, the Soviet Union, with the acquiescence and support of the German Reich, pursued a policy of expansion within the zone of influence granted to it by the Hitler-Stalin Pact. It exerted pressure on several neighboring states with the aim of regaining territories that had belonged to tsarist Russia until 1917/18. Finland opposed this policy during the Winter War (1939/40), during which the weakness of the Red Army became apparent. Although the Soviet Union was able to annex large parts of Karelia, it had to continue to recognize Finland's state independence. In contrast, the Red Army occupied Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania without a fight in mid-June 1940. Under the pretext that the mutual assistance pacts concluded the previous year were in jeopardy, the Soviet Union declared these countries to be union republics. With the occupation of Bessarabia by Soviet troops on June 28, 1940, their expansion ended for the time being.

Stalin and his generals had originally assumed that Germany would be involved in a protracted war with the Western powers and that they would have enough time to prepare the Red Army for a possible conflict. However, the rapid victory of the Wehrmacht in the Western campaign over France (1940) had dashed these hopes. Stalin responded to the new situation with two fundamental decisions: First, he wanted to maintain the alliance with Germany at all costs and not provoke Hitler to war. Second, he tried to improve the Soviet Union's strategic position by exerting further pressure on neighboring states. Thus, beyond the territories of Bessarabia conceded in the Hitler-Stalin Pact, the Red Army occupied northern Bukovina and the Herza region. In addition, Stalin proposed a Baltic-style mutual assistance pact to Bulgaria (see History of Bulgaria). This created tensions with Germany.

At that time, however, Hitler had long since decided to go to war against the Soviet Union. As early as September 4, 1936, Hermann Göring explained Hitler's August memorandum on the Four-Year Plan to the cabinet. It served the political objective of crushing the Soviet Union with a war of aggression in the inevitable confrontation with it. Victory in the East was to make Germany economically self-sufficient on the Continent and a British naval blockade, as had existed in World War I, ineffective. Beginning on June 2, 1940, Hitler had communicated to confidants in the Army High Command (OKH) his thoughts for an attack on the Soviet Union. On July 29, 1940, Alfred Jodl, chief of the Wehrmacht Joint Staff, informed his staff of Hitler's decision to "[...] eliminate the danger of Bolshevism once and for all at the earliest possible moment by a surprise invasion of Soviet Russia." On July 31, 1940, Hitler informed the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) of his decision to attack and ordered operational preparations for war. He now justified the two-front war, notwithstanding Soviet treaty loyalty, on the basis of the alleged danger that unconquered Britain might ally with the Soviet Union and thus use it as a "continental sword" against Germany. He had the Norwegian-Finnish border fortified, concluded a transit agreement with Finland, and sent so-called training troops to Romania. In addition, Germany and Italy guaranteed the Romanian borders. In return, Stalin had a Romanian group of islands in the mouth of the Danube and the strategically important Snake Island offshore occupied.

On November 12, 1940, Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov visited Berlin at the invitation of the German government to discuss the Soviet Union's possible entry into the Three-Power Pact. Hitler ordered the OKW on the same day to continue attack preparations as planned regardless of the outcome of the scheduled talks with Molotov. Molotov made accession conditional on concessions such as increased Soviet influence in Hungary, Yugoslavia, Greece, and Turkey, and further concessions in Finland and Romania. Moreover, in a note of November 25, 1940, the Soviet Union demanded that Japan cede to it the mining concessions on northern Sakhalin. Despite several requests, Hitler did not reply to this note. Neither did he want to see the Finnish nickel area and the Romanian petroleum area within reach of the Soviet Union, nor did he want to persuade the Japanese to give up their naphtha and coal mines. Today, however, historians assume that for Hitler's policy "Soviet behavior at best gave occasions and pretexts for the about-turn, but did not cause it."

In particular, Hitler rejected Molotov's instructed demand for further concessions regarding Finland's neutrality. This was interpreted by the Red Army leadership, which at the time was planning a further occupation of Finland, as Hitler's plan for war. Stalin, however, did not change his policy toward Germany: in January 1941, the Soviet Union concluded an agreement with Germany on the continued supply of raw materials for armaments. A conversion to a war economy was omitted. Because of the economic and strategic advantages for both sides from this agreement, Stalin assumed that Hitler also wanted to maintain the status quo for the time being. His expansive Balkan policy and the Japanese-Soviet neutrality pact concluded on April 13, 1941, were to give the Soviet Union enough time for increased rearmament.

German war planning

Instruction No. 21

Following Hitler's announcement of his decision to go to war on July 31, 1940, the OKW, OKH, and OKM began strategic war planning and each had independent attack studies prepared, which were consolidated beginning on September 3 and presented to Hitler on December 5. On December 18, 1940, Hitler, as "Führer and Supreme Commander of the Wehrmacht," issued Directive No. 21 to the Wehrmacht Leadership Staff in the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW): with it, he ordered the high commands of the three Wehrmacht branches to prepare the attack on the Soviet Union in a targeted manner by May 1941 in order to "also defeat Soviet Russia in a rapid campaign (Fall Barbarossa) before the end of the war against England." The objective was to "destroy the mass of the Russian army standing in western Russia" and to reach a line from which the air forces of the Soviet Union could no longer attack German territory. The ultimate objective of the operation was to "shield against Asiatic Russia on the general line Volga-Arkhangelsk," that is, to occupy most of the European Soviet Union.

Conquest strategy

Unlike the Western campaign, Hitler and the Wehrmacht leadership largely agreed on the strategy and objectives of this war. The operational attack plans of the three Wehrmacht components drawn up by then envisaged a chain of encircling movements and encirclement battles aimed at destroying the Red Army. While Walther von Brauchitsch and Franz Halder mainly wanted to advance directly on Moscow, however, Hitler ordered in his Directive No. 21 that the "center of the total front should only create conditions for turning fast troops into Leningrad and the Donets Basin." Hitler wanted to reach the targeted line in a blitzkrieg of up to 22 weeks; General Erich Marcks calculated only up to 17 weeks. Fast units were to make wedge-shaped breaches in the Red Army defenses, cutting them off from rearward communications and preventing their formations from evading; marching units were to encircle them. After that, the motorized forces were to push further east.

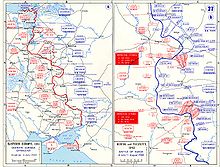

The German Eastern Army was divided into three army groups:

- Army Group North (Leeb) with the 16th Army (Busch), Panzer Group 4 (Hoepner) and the 18th Army (Küchler).

- Army Group Center (Bock) with 4th Army (Kluge), Panzer Group 2 (Guderian), Panzer Group 3 (Hoth), 9th Army (Strauss) and 2nd Army (Weichs).

- Army Group South (Rundstedt) with 17th Army (Stülpnagel), Panzer Group 1 (Kleist), 6th Army (Reichenau) and 11th Army (Schobert).

- from Northern Norway, which was already occupied at the time, and from Northern Finland, two corps of the Army High Command Norway (Falkenhorst).

The Luftwaffe competed with four air fleets, each of which operated within the area of an Army Group but was independent:

- Luftflotte 1 (Keller; area of Army Group North)

- Luftflotte 2 (Kesselring; area of Heeresgruppe Mitte)

- Luftflotte 4 (Löhr; area of Army Group South)

- Air Fleet 5 (Stumpff; units stationed in northern Finland and northern Norway only).

Attacks against the Soviet Union were also to be launched from Norway. They were aimed in particular at Murmansk and the railroad connection there, the Murman Railway, through which British and U.S. aid supplies later reached the Soviet Union. Several ventures in the direction of Murmansk ("Unternehmen Silberfuchs", "Platinum Fox") and on the Murman Railway ("Unternehmen Polarfuchs") were unsuccessful. This was due on the one hand to the extreme climatic conditions, the long polar night and the pathless tundra terrain, and on the other hand to the weak German forces here.

The six-week Balkan campaign, which began in April 1941, delayed the scheduled attack date by a month, although military leaders also believed it would improve the initial chances for the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Despite the delay, the Wehrmacht leadership planned to achieve decisive victories before the onset of Rasputitsa, the so-called "mud season," and to complete the campaign by the onset of winter. About 50 to 60 occupying divisions were to remain in the country; only for them was special clothing adapted to the Russian winter planned.

Extermination plans and murder orders

After the strategic war planning of the Wehrmacht, it entered its concrete operational phase in the spring of 1941. Now its tasks were coordinated with those of the SS, which had been expanded into a parallel army in some areas from 1941, and various police forces for the areas to be conquered.

On March 13, 1941, Hitler issued the directives on special areas to the directive Barbarossa: With this, he assigned Heinrich Himmler, since 1934 the "Reichsführer SS", special powers for "special tasks on behalf of the Fuehrer, which result from the final struggle to be fought between two opposing political systems". For this purpose, the Reich Security Main Office set up four so-called Einsatzgruppen. According to Hitler's guidelines, they were to murder all "suspicious" and "other radical elements" as well as "Jews in party and state positions." Heydrich specified Hitler's murder order with secret orders to the leaders of the Einsatzgruppen to incite pogroms against Jews by the local population.

On March 30, 1941, Hitler proclaimed before 250 Wehrmacht generals the coming war as a "struggle of two world views against each other" and a "war of annihilation." He called for the "annihilation of the Bolshevik commissars and the communist intelligentsia." This intention and demand flowed into some orders of the OKW and OKH for the coming war.

According to the decree on the exercise of wartime jurisdiction in the Barbarossa area of May 13, 1941, crimes committed by members of the Wehrmacht against civilians no longer had to be prosecuted. The decree freed Wehrmacht soldiers from ties to international law norms and encouraged arbitrary and violent acts against the Soviet population. The Guidelines for the Conduct of Troops in Russia of May 19, 1941, required troops to "ruthlessly and vigorously crack down on Bolshevik agitators, free agents, saboteurs, Jews." The Guidelines for the Treatment of Political Commissars of June 6, 1941, ordered the Wehrmacht to "in principle finish off political commissars immediately at gunpoint." The Prisoner of War Regulations of June 16, 1941, called for "ruthless and vigorous crackdowns on the slightest signs of recalcitrance, especially against Bolshevik agitators." Accordingly, the Ten Commandments for the conduct of war by the German soldier, which were pasted into the covers of every pay book and forbade inappropriate cruelty or conduct contrary to international law, were suspended. After the war began, some of the murder orders were further tightened or their scope expanded. For example, on July 2, 1941, Reinhard Heydrich ordered the "Higher SS and Police Leaders" to implement the Commissar Order of June 6 as follows: "To be executed are all functionaries of the Comintern (as well as, in general, Communist professional politicians par excellence), the higher, middle, and radical lower functionaries of the Party, the Central Committees, the Gau and Area Committees, People's Commissars, Jews in Party and state positions."

With these criminal orders, the Nazi regime prepared the German-Soviet War as a war of extermination. OKW and OKH passed on the orders to lower officer ranks; objection of the recipients against it was missing. Thus, the Wehrmacht allowed itself to be integrated into Hitler's Lebensraum program. Specialized historians explain this with the anti-Semitic, racist, anti-Bolshevik and anti-Slavic character of the German officer corps, which blamed the November Revolution of 1918 on Jews and communists, equating them, the long-standing Führer cult, imperialist goals and hubris after the Western campaign. Hitler's war aims and those of the Wehrmacht leadership largely coincided: for example, some leading generals envisaged the goal of crushing the Soviet Union and exploiting its territory for economic "autarky" for Germany even before Hitler's decision to go to war on July 31, 1940. In March 1941, therefore, they also endorsed the deemed necessary task of breaking expected Soviet resistance through terror in order to "create calm in the rear of the front" and regarded Einsatzgruppen set up for this purpose as a relief.

Wehrmacht logisticians calculated that German units could be supplied only to a line along Pskov, Kiev, and the Crimea. Since Hitler demanded the conquest of Moscow in the course of a single uninterrupted campaign, the Wehrmacht was to be supplied by the ruthless requisitioning of food and material essential to the war effort from the areas to be conquered. Because an annual requirement of five million tons of grain from the USSR was calculated to secure the food supply of the German Reich, whereas in 1940 the USSR had been able to supply only 1.5 million tons on a commercial basis, Göring's Four-Year Plan authorities planned before the invasion to exploit the largest possible quantities of grain, meat, and potatoes by deliberately undersupplying the Soviet population. The entire Wehrmacht was to be fed by "extracting from the country what is necessary for us"; in the process, it was calculated that "undoubtedly tens of millions of people would starve to death." In this starvation policy, the Nazi regime combined war-economy considerations of utility with racist motives. Christian Gerlach sees this as a starvation plan; other historians deny a decided plan and speak of a "hunger calculation." Based on the relevant documents, most historians see no contradiction in this. Eastern European historian Hans-Heinrich Nolte estimates seven million starvation deaths among a total of 26 to 27 million Soviet war dead; he takes Russian research into account. Yale historian Timothy Snyder cites 4.2 million Soviet famine deaths in Wehrmacht-occupied territories.

In addition, Himmler had initiated comprehensive plans for the deportation ("resettlement") of "Slavs" by the millions and the subsequent "Germanization" of conquered territories from September 1939 and had begun to implement them in Poland, with tens of thousands of the deportees already dying. These plans were enormously expanded from 1941 and integrated into a "General Plan East". This planned to shift the German "Volkstumgrenze" almost 1000 km to the east, to expel the majority of the Soviet citizens living there, initially estimated at 30, in 1942 up to 65 million, behind the Ural Mountains or to Siberia and to use some hundred thousand "Slavic subhumans" as labor slaves for the construction of "defense settlements" for "Teutons" or "ethnic Germans".

Role and goals of allied states

The Nazi regime considered Finland and Romania as "natural allies" because of their recent conflicts with the Soviet Union and did not conclude formal agreements with these states for a wartime coalition. They were informed in advance about the planned attack so that they could prepare their troop deployment.

Finland under Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim wanted to regain the territories lost in the Winter War. It closed in on the border with an army on both sides of Lake Ladoga and granted German troops stationing rights in northern Finland.

At the beginning of the German campaign, Romania under Marshal Ion Antonescu was the most important ally in terms of numbers and at the same time probably the one most motivated to join forces. It participated in the Eastern campaign on June 22 with 325,685 men and 207 aircraft. The clear goal of the Romanian leadership was to regain the territories annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940, although Romanian occupation desires beyond this also played a role. Antonescu was the only foreign head of government to be personally informed of the impending attack at a meeting with Hitler in Munich on June 11-12, 1941. The Romanian 3rd and 4th Armies were moved to the country's eastern border to join the German 11th Army in attacking the southern Soviet Union and retaking Soviet-occupied Bessarabia. From the Romanian territory, the German "Einsatzgruppe D" began exterminating Jews.

Italy declared war on the Soviet Union on June 23, although there had been diplomatic overtures between the two countries in the months before. Negotiations, however, had been repeatedly disrupted by German intervention, and the German attack on the Soviet Union sealed their end. Benito Mussolini sent an expeditionary force of 62,000 men, 220 guns, and 83 aircraft. Hungary, on the initiative of its imperial administrator Miklós Horthy, sent two corps with 45,000 men, including a motorized one with 160 tanks. The Slovak Republic, which had become independent, sent its "fast division" and later two securing divisions. Croatia sent several "legions" in succession. Spain under Francisco Franco sent some 15,000 volunteers to the Eastern Front, who wore a blue scarf with their Wehrmacht uniform and fought as the Blue Division under Wehrmacht command.

From eight countries and regions a total of about 43,000 "foreign volunteers" came in 1941 to support the "European crusade against Bolshevism" and the "new racial order". Larger volunteer units gathered in France, Holland, and Belgium, and smaller ones from Scandinavian countries. They were either integrated into the Wehrmacht or wore the uniforms of the Waffen-SS.

Soviet defense preparation

The Communist leadership saw the Soviet Union as surrounded by a capitalist world hostile in principle and considered war with it inevitable. In February 1931, at the All-Union Conference for Industrial Officials, Stalin expressed, "We are 50 to 100 years behind the advanced countries. We must go the distance in ten years. Either we can manage it or we will be crushed." As a result, the Five-Year Plans have involved unusually high armaments efforts. These were achieved at the expense of living standards. By 1935, the Red Army had 10,180 tanks and 6,672 aircraft. Plans called for an inventory of 90,000 tanks and 15,000 aircraft. The Nazi seizure of power went far beyond the level of tension in which Soviet foreign policy was generally interested, as real possibilities for conflict were seen. The Comintern's main organ, the Rundschau über Politik, Wirtschaft und Arbeiterbewegung (Review of Politics, Economics, and the Workers' Movement), commented on the Westerplatte incident of March 6, 1933, as an "aggravation of the danger of war between Germany and Poland" and said that Danzig could one day become "the signal for the ignition of an imperialist war." On March 22, 1933, Pravda noted in an article "Where is Germany Headed?" that "The National Socialists have developed a foreign policy program against the existence of the USSR," and demanded that the German government state clearly where it was headed. At the XVII Party Congress of the CPSU in 1934, Nikolai Bukharin read out the passage from Mein Kampf where Hitler spoke of conquering the Soviet Union and commented:

"This is the enemy, comrades, that we are up against! He will face us in all the formidable battles that history imposes on us".

From 1934 onward, the Red Army's military strategy was based on forward defense: An attack was to be answered as soon as possible with offensive counterattacks in order to fight the battle on the enemy's territory and defeat him there. Germany with its allies Italy, Romania and Hungary were considered as possible main opponents in the west, which could deploy up to 300 divisions in case of war. In September 1940, the Soviet General Staff under Boris Mikhailovich Shaposhnikov quite realistically anticipated the course of the later two German lines of attack, attempts at encirclement, subsequent German advances on Moscow and Leningrad, and a war lasting several years, which would require sustained and broad mobilization.

After the German invasion of Poland, the Soviet Union began to establish the Molotov Line along the new border with the German Reich, replacing the Stalin Line, some 300 kilometers to the east, as the western line of defense. The mobilization plan, tailored for offensive defense and envisioning a strength of 7.85 million soldiers in the European and Caucasian military districts of the USSR, had to be reformed after the occupation of eastern Poland and the Winter War against Finland. A redraft by Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko and Kirill Afanasyevich Merezkov in September 1940 provided for a counteroffensive south of the Pripyat Marshes in the event of a German attack. Stalin put it into effect in October 1940, but ordered a concentration of troops in the Kiev area to counter a feared German advance to occupy Ukraine and the Caucasus. From February to May 1941, troop deployment, distribution, command structures, and supply lines of the western military districts were changed several more times. In the process, the previous strategy of an immediate broad counteroffensive was abandoned in March 1941; this was now to take place at most in some sections of the front and only after full mobilization and successful repulse of enemy advances. Beginning in May 1941, the Red Army drew together additional divisions from other parts of the country in the western military districts and distributed them along the entire western frontier. In doing so, it followed Stalin's directives of October 1940 and responded to the German troop buildup of which it was aware.

The preemptive war thesis that Hitler's attack was merely a preemptive response to a Soviet offensive has therefore been scientifically refuted. Rather, the Red Army's deployment was a reaction to German war preparations in the sense of the doctrine of forward defense. This was well known to the Wehrmacht leadership. The German "Abteilung Fremde Heere Ost" (Foreign Armies East Department) in the OKH, which meanwhile resumed the contractually forbidden German reconnaissance flights over Soviet territory, assessed the Soviet troop reinforcements unanimously and continuously from April to June 1941 as purely defensive. According to Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, the OKH and the Nazi regime even regarded the Soviet troop concentration near the border as "the best thing [...] that can happen at all" because it facilitated the planned "push-through" and made possible "an easy prisoner haul."

Stalin and his generals assumed that the Red Army would not be ready to defend itself against the Wehrmacht before 1942, mainly because the generals and officers killed by the "purges" of 1936 to 1938 could not be replaced quickly enough by competent men. In Stalin's May 5, 1941, speech in the Kremlin to graduates of Soviet military academies, he declared, "We must pass from defense to the military policy of offensive action. We must rebuild our education, our propaganda, agitation, our press in the offensive spirit." He thus wanted to swear the Red Army's junior officers to the implementation of the offensive strategy in effect from October 1940, partly because he expected the Soviet Union to enter the war from 1942.

The Soviet military intelligence service GRU had informed Stalin for the first time on January 20, 1940, then on April 8 and June 28, as well as on September 4, 27, and 29, 1940, about possible German war intentions against the Soviet Union, and on December 29, 1940, also about Hitler's "Directive No. 21." The NKVD also reported six times between July 9 and November 6, 1940, on German troop movements to the eastern border of the Reich. In 1941, such reports became more frequent. Stalin had them all sent to him directly and without comment, but he did not consult them and thus reserved the right to select and interpret them in accordance with his policy. In early May 1941, Richard Sorge, an agent working in Japan, reported to the Soviet Union that the German attack was to begin with 150 divisions on June 20. But Stalin, who did not believe in a German surprise attack, would not take note of Hitler's obvious intention to attack until the war began. He judged all substantial warnings from circles of the German resistance as well as from the British and Soviet secret services as deliberate disinformation with which Great Britain was trying to draw him into the war against Germany. The flight of Hitler's deputy Rudolf Hess to Britain on May 10, 1941, on his own initiative to try to broker a peace between the two states, also contributed to this. The British, for their part, spread rumors that Hess might succeed in doing so in order to provoke the Soviet Union into ending its alliance with Germany or even into a preemptive strike. Stalin, however, thought it impossible that Hitler would start a two-front war until he had made peace with Britain. Until then, he wanted to wait and not be provoked. This misjudgment contributed significantly to the later initial successes of the Wehrmacht.

On May 15, 1941, the People's Commissar for Defense, Marshal Timoshenko of the Soviet Union, and the Chief of the General Staff of the Red Army, Army General Zhukov, presented Stalin with a plan for a preemptive strike against the German buildup. However, according to their concurring postwar statements, the latter strictly rejected the proposal and forbade them to take such action. Nevertheless, the Red Army strengthened its offensive deployment; whether it initiated a covert partial mobilization is judged differently by military historians. Stalin's order to do so is not documented.

On June 13, 1941, the Soviet leadership finally decided to hold 237 of 303 Soviet divisions with six million soldiers in four front sections near the border against an attack from the west. To this end, about one-third of the personnel and motor vehicles were to be brought in from the interior. In addition, the assumed inferiority of the air forces was to be compensated for by 100 new aviation regiments by the end of 1941. As a result of the constantly reformed plan, the full mobilization originally planned for the end of May 1941 was missed; once the war began, it could not be implemented as planned. The Molotov Line was not yet completed; 60 percent of the finished bunkers lacked armament and communications. Only 13 percent of the planned heavy tanks, 7 percent of the medium tanks, 67 percent of the combat aircraft, 65 percent of the antiaircraft guns, 50 to 75 percent of the communications equipment were ready for use when the war began. The defense squadrons could not reach their staging areas fast enough, so they were easily cut off from each other and from supplies. The Red Army General Staff had not planned for a German surprise attack before the target strength of its troops was reached, assuming early detection of enemy intentions and timely deployment orders from Stalin. The head of the Military Council of the Leningrad Military District, Andrei Alexandrovich Zhdanov, took a recuperative leave on June 21 for health reasons. Despite many warnings by defectors and diplomats, only Moscow's air defenses were initially brought to 75 percent combat readiness on June 21. On the night of June 21-22, after several hours of consultation with his generals, Stalin had troops in the border districts put on alert. In many places, however, the Soviet units were surprised by the German attack that immediately followed. Stalin, too, reacted with shock.

As a result of the German invasion, Stalin had the "Great Patriotic War" (Russian Вели́кая Оте́чественная война́, Velikaya otetschestwennaja wojna) proclaimed. The editorial of Pravda by Yemelyan Mikhailovich Yaroslavsky on June 23, 1941, was titled: "The Great Patriotic War of the Soviet People." Stalin himself called it "patriotic" in his first radio address after the war began on July 3, 1941, and again in a speech on November 6, 1941. Russian historiography had already called the Russian campaign of 1812 "Patriotic War". The term was also common in the Eastern bloc after 1945 and is still used today in Russia and other successor states of the Soviet Union. His volume On the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union, published in Moscow in 1946 and containing speeches and orders by Stalin, aimed to portray the fighting as a "just patriotic people's and liberation war."

State Visit of Marshal Antonescu to Munich on June 11-12, 1941

Molotov signs the German-Soviet Border and Friendship Treaty in the Moscow Kremlin on September 28, 1939

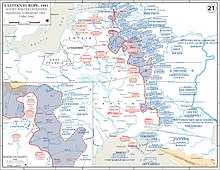

Planned directions of advance in Unternehmen Barbarossa (1941)

Military balance of power

Troop and weapon numbers at the start of the war

Military historians David Glantz and Mikhail Ivanovich Meltyukhov have given various figures on the relationship between the two forces on June 22, 1941:

| Force | Axis powers | Red army | ||

| Author | Glantz | Meltyukhov | Glantz | Meltyukhov |

| Soldiers | 3.767.000 | 4.306.800 | 2.780.000 | 3.289.851 |

| Tank | 3.612 | 4.171 | 11.000 | 15.687 |

| Aircraft | 2.937 | 4.846 | 9.917 | 10.743 |

| Protected | 12.686 | 42.601 | 42.872 | 59.787 |

The approximately three million soldiers of the German Eastern Army were distributed among 150 divisions, including 20 armored divisions. The allies provided another 690,000 soldiers. These troops were divided into three army groups with a total of ten army high commands and four armored groups. In addition to the above weapons, they had 600,000 motor vehicles and 625,000 horses. In the western military districts of the Soviet Union they were opposed by 2.9 million Red Army troops, 145 divisions and 40 brigades, divided into four army groups with ten army high commands.

According to a list in the work Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweiten Weltkrieg (The German Reich and the Second World War), compiled by historians of the Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (Military History Research Office), by the start of the war on June 22, 1941, the German Army had transferred 3648 of 5694 tanks and assault guns of its then total inventory (~ 64%) to the Eastern Front, including 3255 Type I-IV armored fighting vehicles, 143 tank command vehicles, and 250 of 377 Type III assault guns. As a result of reorganizations since the 1940 Western campaign, the Wehrmacht had almost doubled the number of its armored divisions, but not its tanks. Accordingly, it had to continue using older or captured foreign models and equipped one-third of its armored divisions with 157 Czechoslovak 35(t) tanks and 651 38(t) tanks. The Panzerkampfwagen I had provided almost half of all German tanks in 1939 and had often been converted to the Panzerjäger I or other purposes thereafter. The eastern armored divisions still used 281 of the original model in 1941, 743 of Panzerkampfwagen II, 651 of Panzerkampfwagen III, 444 of Panzerkampfwagen IV, and Schützenpanzerwagen Sd.Kfz. 251. The Panzerkampfwagen IV with its short 7.5-cm gun (L/27) was not very suitable for breakthrough operations. The 250 examples of the Sturmgeschütz III (subordinate to the artillery) with its equally short gun were mainly intended to support the infantry. Although each armored division was to have an armored infantry battalion, most were equipped with only an armored rifle company because of the lack of vehicles.

Among Soviet tanks, only about 27% of the old tank types were reported to be operational. On June 15, 1941, 29% of all tanks needed major repairs and 44% needed medium repairs.

For organization of forces, see Schematic War Organization of the Red Army on 22 June 1941 and Schematic War Organization of the Wehrmacht on 22 June 1941.

Weaponry development

Secret German-Soviet military cooperation until the early 1930s had contributed to a modernization of Red Army strategy and armament under Marshal Tukhachevsky, which military historians believe made the Soviet counteroffensives of 1941 to 1944 largely possible.

Ground forces

The artillery weapons of the Wehrmacht and the Red Army were considered roughly equivalent. The situation was different with the tank weaponry. The German tank models Panzer I, Panzer II, Panzer 35 (t), Panzer 38 (t) and also the Panzer III had too little armor and firepower compared to the heavy Soviet models. Therefore, the Wehrmacht often had to use flak artillery to break through the heavy armor of the KW-1 and KW-2. However, at least the Panzer III and IV proved superior to the Soviet tank models T-26, T-28, T-35, BT-5 and BT-7, some of which were obsolete in 1941.

The Soviet KW-1 and KW-2 heavy tank models were quite resistant to most German army anti-tank weapons. The Luftwaffe was mainly used to combat them. The modern T-34 medium tank was very fast, well armed, and adequately armored, but was not used in large numbers by the Red Army at the beginning of the war. The first prototypes still had shortcomings in the areas of propulsion and all-round visibility, and initially there were hardly any radios available. However, the T-34 was continuously improved during the war, and a total of over 50,000 units were produced. It is therefore considered the "standard tank" of the Red Army. Only the medium German tank V (Panther) and the heavy VI (Tiger) were qualitatively equal to the T-34, but they still suffered from development deficiencies in 1943 and could no longer be produced in sufficiently high numbers. With the appearance of the JS-1 and JS-2 heavy tanks, the Red Army finally had the most effective tanks of the war at its disposal. In order to meet the quantitative requirements of tank warfare, both sides used so-called assault guns and sometimes improvised-looking self-propelled guns and tank howitzers by, among other things, mounting captured guns on existing tank chassis. The Red Army's gun models were all relatively simple, reliable and robustly built, and thus much better suited for mass production than the more sophisticatedly designed and often hand-built German gun models.

Air Force

Although the Soviet Union's air forces already had combat-experienced pilots from the battles at Chalchin Gol against the Japanese and from the Winter War against Finland in 1941, they were often prevented from putting their experience into practice by strong political indoctrination. The lack of radios made effective command and control virtually impossible.

In the area of equipment, structure, and tactics, a clearly noticeable change took place in the Soviet air forces beginning in 1942. The Stavka began to form independent air armies from the air regiments, which until then had been subordinated to the "fronts" (army groups), which could support these fronts but were independent in their organization. Under the leadership of General Novikov, who was appointed commander-in-chief of the air forces in 1942, 18 air armies were formed, each of which roughly corresponded in size and structure to an air fleet of the German Luftwaffe.

In the area of fighter aircraft, the Soviet Union was still using some aircraft types from the Spanish Civil War period until April 1942, but by the end of the year most regiments had upgraded to more modern types such as MiG-3, LaGG-3 and Yak-1. Deliveries of fighters and radios from the U.S. and Britain contributed significantly to modernization during this period.

Technically, these types were still inferior to a certain extent to the Bf 109 F/G and FW-190 used by the German Luftwaffe, partly because of deficiencies in armament and equipment, stability and flight performance. The La-5, La-7, Jak-3, Jak-7 and Jak-9 models produced from 1942 onward were also able to match the Luftwaffe aircraft in every respect in terms of quality. As early as 1941, British Hawker Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfires were delivered to the Soviet Union as part of the loan and lease agreement, and numerous Bell P-39 and Curtiss P-40 fighters arrived from the United States.

As early as the invasion of Poland in 1939, the German Wehrmacht effectively employed tactical air units in conjunction with armored troops. This tactic was effectively adopted by the Red Army in its offensives beginning in 1942. On the Soviet side, the counterpart to the Ju 87 dive bomber, which was already obsolete and vulnerable by 1941, was the heavily armored Ilyushin Il-2. To this day, the Il-2, with over 36,000 completed, is considered one of the most widely built aircraft in the world, along with the Po-2. Both the Ju 87 and the Il-2 underwent further development during the course of the conflict and were geared toward anti-tank combat.

As medium bombers, the German Ju 88 and He 111 were opposed by the Soviet Pe-2, IL-4 and, from 1943, Tu-2, all of which were capable of a variety of tasks and balanced advantages and disadvantages in terms of quality. While minor technical advantages were evident on the German side, the Soviet bombers had more experience and were better equipped for the winter war. More than 3,000 Douglas A-20 bombers and a relatively small number of about 800 North American B-25 bombers were delivered to the Soviet Union under the Lend-Lease Act and were used until the 1950s. The heavy strategic bombers of both opponents in the conflict were of secondary importance except for a few long-range sorties by Soviet Pe-8 bombers.

Transport aircraft had a special role to play. In the winter of 1941/42, trapped units near Demjansk and Cholm were supplied by air despite heavy losses; the missions were largely flown by Ju 52s, a military-adapted airliner from 1932. Despite its age, this type was able to perform the task because of its robustness. However, the attempt to supply Stalingrad by air in the winter of 1943 failed due to a lack of capacity, the weather and Soviet air defenses, among other reasons. Ju 90s, Heinkel He 177s and Fw 200s were also used in this airlift. The Soviet Union received permission to build the powerful U.S. Douglas C-47 under license; it designated it the Li-2 and discontinued its own previously produced models. Like the Ju 52, the Li-2 could be used as a transport aircraft or as an auxiliary bomber and could be equipped with on-board weapons. On both sides, many other types of aircraft were used in addition to the aforementioned models.

War production

The German economy was only gradually converted to a wartime economy from 1941 onward. The rationalization measures initiated by Fritz Todt for cheap and technically simple mass production did not take full effect until 1944 under his successor Albert Speer. Until then, the elaborate manual production of precision weapons favored by military procurement agencies predominated, so that the Wehrmacht used a large number of different and high-maintenance weapon systems. Until 1942, the factories still mostly worked in only one shift.

Industrial exploitation of the raw material reserves resulted in relatively high production volumes. However, the raw material reserves of the Axis powers were scarce overall and hardly lasted beyond a six-month war.

The Soviet Union had many more raw material reserves at its disposal, but due to the initially unfavorable course of the war with the relocation of many industrial plants to the east, it was not able to fully exploit them until the end of the war. Thanks to more advanced rationalization and standardization, the Soviet defense industry was able to produce more armaments from fewer raw materials than the German Reich.

| Soviet (red) and German (blue) war production | |||||

| Armaments and heavy industry (selection) | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 |

| Aircraft | 15.735 | 25.436 | 34.900 | 40.300 | 20.900 |

| 11.776 | 15.409 | 28.807 | 39.807 | 7.540 | |

| Tank | 6.590 | 24.446 | 24.089 | 28.963 | 15.400 |

| 3.804 | 5.997 | 12.151 | 19.087 | 4.400 | |

| Coal (in million tons) | 151,4 | 75,5 | 93,1 | 121,5 | 149,3 |

| 315,5 | 317,9 | 340,4 | 347,6 | no data | |

| Steel (in million tons) | 17,9 | 8,1 | 8,5 | 10,9 | 12,3 |

| 28,2 | 28,7 | 30,6 | 25,8 | no data | |

| Oil (in million tons) | 33,0 | 22,0 | 18,0 | 18,2 | 19,4 |

| 5,7 | 6,6 | 7,6 | 5,5 | 1,3 |

The limited number of motorized units of the Wehrmacht was partly upgraded with looted vehicles from the Western campaign in preparation for Operation Barbarossa. In the process, new large units often received looted vehicles (trucks and passenger cars), while in some cases at the same time, especially in the Luftwaffe, the much more suitable German-built vehicles remained in the West. Overall, this improved armament situation allowed the Wehrmacht to conduct long-range attack operations appropriate to the blitzkrieg concept. In addition, 650,000 horses were added in 1941 and up to two million in 1944. The German motor vehicle industry was less efficient than that of other industrialized nations, except for motorcycles. Even before the war, the motorized equipment of the civilian population was high. Consequently, Kradschützen units were formed, which were the fastest and most mobile armament of the Rapid Troops. However, they were quickly worn out in the traffic conditions, which were severely affected by dust, mud, snow and frost, and were therefore soon disbanded.

The Göring program of June 23, 1941, was intended to shift the armament focus to the Luftwaffe for the fight against the Western powers, but it could not be realized.

Despite the defeats of 1941/42, the Soviet Union was able to gradually secure supplies of arms and munitions for two main reasons: A large part of its industrial plants to the west for the urgently needed armaments were dismantled in time to be rebuilt east of the Urals beyond the reach of the German air force. Great Britain and, from August 2, 1941, the USA also supplied equipment, motor vehicles, foodstuffs, raw materials such as aluminum, and weapons (→ Lending and Leasing Act). This compensated for temporary production slumps at Soviet armaments plants. During the war, the U.S. supplied 57.8 percent of aviation fuel, 53 percent of all explosives, nearly 50 percent of copper, aluminum, and rubber tires, 56.6 percent of all rails laid during the war, 1900 locomotives, and 11,075 freight cars. This contrasted with 92 locomotives and 1087 freight cars of Soviet manufacture. At the end of 1942, only five percent of Soviet military vehicles were of foreign production; by the end of the war, over 30 percent were. By weight, nearly 50 percent of all U.S. supplies were food.

After the relocation of the industrial plants, Soviet wartime production grew rapidly until 1944 and surpassed German production in many areas: For example, the technically simple weapons systems consumed fewer raw materials. From a much smaller quantity of iron ore than in Germany, an equal quantity of guns, tanks and aircraft was produced. The Soviet Union benefited from the centralization of the economy.

German Messerschmitt Bf 109 in Northern Russia, 1942

Soviet Ilyushin Il-2 during the battle of Kursk, summer 1943

.jpg)

Repair on a tank V, 1944

BT-7, A-20, T-34 model 1940 and T34 model 41 in comparison

Course 1941

German announcements of the attack

On June 22, 1941, early in the morning at 4 a.m. CEST, the German ambassador, Friedrich-Werner Graf von der Schulenburg, presented a "memorandum" to Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov in Moscow: the Soviet Union had broken the non-aggression pact by deploying the Red Army on the border, conspiratorial activity of the Comintern in Germany, and the annexation of eastern Poland and the Baltic states, and had thus "stabbed warring Germany in the back." The Wehrmacht had orders to "counter this threat with all available means of power." The word "declaration of war" had to be avoided on Hitler's orders; however, when asked by Molotov, Schulenburg confirmed that it was. German planes had already been bombing Soviet cities for three hours.

Shortly after 4 a.m., German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop delivered a note to Soviet Ambassador Vladimir Georgievich Dekanosov, which he announced to the international press at about 6 a.m. The note said that the Soviet Union had "turned against Germany with its entire armed forces". The text justified the attack on the grounds that the Soviet Union, "contrary to all the commitments it had assumed and in stark contrast to its solemn declarations," had "turned against Germany" and "marched up with its entire armed forces on the German border, ready to jump."

At 5:30 a.m., Propaganda Minister Goebbels read out a "Proclamation of the Fuehrer to the German People" over all German radio stations. The core statement read: "To ward off the imminent danger from the East, the German Wehrmacht has entered the midst of the enormous deployment of enemy forces at 3 a.m. on June 22." A little later, the Russia fanfare introduced the OKW's "Radio Special Messages."

With these public statements, Nazi propaganda began a long prepared campaign to justify the invasion, which the regime adhered to until the end of the war, and many Wehrmacht generals even beyond. Historical research has rejected this preemptive war thesis as baseless since 1960 and completely refuted it by 2000.

Initial successes of the Wehrmacht

In the early morning hours of June 22, 1941, the advance of 121 German divisions began on a 2130 km wide front between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea, divided into three army groups (South, Central and North). The invasion force consisted of three million German soldiers plus another 600,000 soldiers from Italy, Hungary, Finland, Romania and Slovakia, 600,000 motor vehicles, 625,000 horses, 3350 tanks, 7300 guns and 3000 aircraft. The fighter planes assigned to the army groups conducted a massive air strike against the Soviet airfields, made possible by the reconnaissance results of the Rowehl Command, destroying about 1200 planes on the ground on the first day of the war alone.

Two divisions operated from Finland on a front 1180 km wide, eight divisions were stationed in Norway, one division was in Denmark, 38 remained in the West. Two divisions were fighting in North Africa (African campaign) and seven divisions had been in the Balkans since April 1941. The 7th Flieger Division, planned for follow-on operations as the 1st Parachute Division, was not available after the catastrophic losses on Crete and was transferred back to Germany.

This force was opposed by 170 Soviet divisions in the western military districts, for the command of which three fronts had been formed, the "Northwest Front", "Western Front" and "Southwest Front". In the days following the German invasion, two more fronts were formed from the Leningrad and Odessa Military Districts, the Northern and Southern Fronts, respectively. The first operational squadron, consisting of 53 rifle and three cavalry divisions, was stationed between 10 and 50 kilometers from the German-Soviet border of interest. Behind it, a second operational squadron of 13 rifle, three cavalry, 24 armored, and 12 motorized rifle divisions stood by as a reserve to repel attackers and seal off incursions. A third echelon of 62 divisions, intended as a strategic reserve, formed along the Dwina and Dnepr rivers 100 to 400 kilometers from the border. Since the deployment had not been completed by 22 June 1941, the Soviet divisions averaged only 60 to 80 percent of their target strength. Some of the mechanized units had no vehicles or only obsolete ones; telecommunications and other special equipment were not available or were available only in small numbers.

For the Red Army, "alert level 1" (full war readiness) existed from June 22, 0:30 a.m., therefore the attackers did not succeed in tactical surprise at all sections. At least, the river crossings necessary for long-range tank movements quickly came into German hands. Nevertheless, more than 300 German aircraft were irretrievably lost to Soviet anti-aircraft fire in the first days of the attack.

Despite sometimes fierce resistance from the Red Army forces, which had been put on alert at too short notice, the German Wehrmacht was able to make major space gains in the first few weeks. Cooperation between ground forces and the Luftwaffe in the battle of the linked arms proved to be extremely effective. The Ju 87s and Bf 110s taken out of combat during the Battle of Britain because of heavy losses were able to perform their missions in the absence of enemy fighter defenses.

The two armored groups of Army Group Center closed their "pincers" first around Białystok and then around Minsk. After the German invasion on June 22, 1941, the People's Commissar for Defense Semyon Timoshenko ordered his troops to advance to the border on the same day, first to destroy the troops that had invaded Soviet territory and then to proceed to the counterattack. On July 9, 1941, the OKW reported 328,898 prisoners, 3102 captured guns, and 3332 destroyed tanks (as many combat vehicles as the German Eastern Army possessed). The reasons for the high numbers were that the Red Army was caught by surprise at the moment of its reorganization, its low mobility, its overestimation of its own capabilities, and the prohibition to withdraw without explicit orders from the General Staff. After clearing the kettles, the Wehrmacht formations continued to advance toward Smolensk, where the Kesselschlacht bei Smolensk (July 10-September 10) - again successful for them - was fought. Completely contrary to previous experience in the Polish and Western campaigns, Soviet troops continued to fight even in the Kessel. Moreover, due to the size of the country, the kettles could never be completely closed. Therefore, in all kettles, Soviet troops could always break out in whole columns, especially at night.

The other German army groups could not report such successes at first. On the wings, the Soviet High Command withdrew its troops from encirclement, surrendering Lithuania, the Dune Line, Bessarabia and western Ukraine. Nevertheless, Army Group North succeeded in sealing off Leningrad in the south and east in early September.

In an assessment of the situation on 25 June, Heeresgruppe Süd had already come to the conclusion that the enemy was a "serious opponent in every respect" in terms of "his will to fight, his combative toughness, and apparently also with regard to his leadership measures". This realization led to a modification of the operational plans in Instruction No. 1 of 26 June. The enemy was no longer to be encompassed and defeated west of the Dnepr, but only along the Bug. In the tank battle at Dubno-Luzk-Rivne, it succeeded in largely destroying several of the Red Army Mechanized Corps engaged here, but with heavy losses of its own. On July 2, two Romanian and German 11th Armies began their attack on the territories occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940. The Romanian 4th Army subsequently began the siege of Odessa. Army Group South had earlier annihilated several Soviet armies in the Kesselschlacht near Uman and thus dominated the Dnieper arc.

The defeats of the Red Army resulted, among other things, in many of its commanders, as well as ordinary soldiers, being arrested and executed for "cowardice," "treason" or "incompetence." Among them was the commander-in-chief of the Soviet Western Front, Army General Pavlov, who was relieved of his command by Stalin on June 28, 1941, and shot along with other officers in Moscow on July 22, 1941.

In order to impede the German advance, paramilitary extermination battalions with a strength of over 300,000 men of the Wehrmacht left scorched earth in their wake.

Only on 30. June, long after the fall of Minsk, a State Defense Committee (GKO) was formed to deal with the complex task at hand and to formulate long-overdue orders (which until then only Stalin himself could issue). In addition to Stalin, the GKO included Nikolai Bulganin (Minister of Defense), Kliment Yefremovich Voroshilov (First Marshal), Nikolai Vosnessensky (Deputy Prime Minister), Lasar Kaganovich (Chief of Railways), Georgy Malenkov (Central Committee Secretary), Anastas Mikoyan (Minister of Trade), and Foreign Minister Molotov, whose leadership Stalin assumed the following day.

On July 12, 1941, Great Britain and the Soviet Union formed an alliance. The U.S. extended the Lend-Lease Act in favor of the Soviet Union. To transport most of the relief supplies, Soviet and British troops occupied Iran on August 24, 1941, and extended supply routes from the Persian Gulf to the Caspian Sea (Persian Corridor). Further Allied deliveries were made by larger convoys across the North Sea from Britain to the port of Murmansk (the northernmost ice-free port in Russia). During the course of the war, convoy battles with the German Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe resulted in heavy losses.

In order to shake the Soviet resistance, the German Luftwaffe began its air attacks on Moscow on July 21. There it encountered comprehensively prepared air defenses and was unable to inflict any major damage.

After the border battles, growing resistance by Soviet forces and counterattacks slowed the German advance from 5 km a day in July, to 2.2 km in August and 1.4 km in September.

Although the guidelines called for a rest period after 4 to 5 days of operations to restore readiness, Hitler drove the tank units to non-stop forward assault. This, combined with a driving distance of 4,000 km by November 1941 under the harshest terrain and climatic conditions, resulted in more tanks failing due to wear and tear than enemy action. As early as August 22, 1941, Heeresgruppe Mitte reported that the tank units were "worn out and used up to such a high degree" that "an operational use of their mass is not to be thought of before a total refreshment." In addition, there was a failure in the supply of spare parts.

In July/August, the failure of the Blitzkrieg plan against the Soviet Union became apparent. This led to the so-called "August Crisis," in which Hitler and the OKH argued about the further conduct of the war. Contrary to an OKH memorandum of August 18, 1941, which proposed a direct attack on Moscow, Hitler ordered the complete seizure of Ukraine and the establishment of a common front with Finland on August 21, 1941, because of the Kessel Battle at Uman, which had just been won, and for political and economic considerations. To this end, he had Army Group Center turn Panzer Group 3 northward, where it was to help isolate Kronstadt and Leningrad, while Panzer Group 2 was shifted southward to support the German advance in Ukraine.

In August 1941, Finnish units occupied the Karelian Isthmus as part of the Continuation War. Beginning on September 4, 1941, artillery of Army Group North, advancing across the Baltic, shelled Leningrad; on September 6, a series of German air raids on the city began. On September 8, the Wehrmacht captured Schlüsselburg on the shore of Lake Ladoga, cutting off all land communications with Leningrad. This marked the beginning of the Leningrad Blockade, which lasted until January 18, 1944. To organize the defense of the city, General Zhukov relieved General Voroshilov and worked closely with Leningrad party leader Zhdanov. On September 25, the front stabilized. Stalin assumed that the city would not be taken, but besieged and starved. He ordered Zhukov to the defense of Moscow, where he flew on October 5. It was not until November 22, 1941, that trucks were able to bring supplies into the city and evacuate refugees across the frozen Lake Ladoga, the so-called "Road of Life." Over a million people died as a result of starvation and cold during the siege; some tried to escape starvation through cannibalism.

On September 26, the Kesselschlacht around Kiev ended with the greatest success of the Wehrmacht so far: according to German figures, about 665,000 Red Army soldiers became German prisoners of war, 2718 guns were captured. Until then, the campaign represented a defeat of unparalleled magnitude for the Soviet Union: The troops of the Soviet southwestern front with four armies as well as strong parts of two other armies were destroyed and the Soviet front was torn in a width of more than 400 km.

In the meantime, euphoria was growing in the German Reich. Now that Hitler had ordered the attack on Moscow, the double battle of Vyazma and Bryansk took place; according to German figures, more than 600,000 Red Army soldiers were also taken prisoner. Due to the tremendous successes, the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht (OKW) announced as early as October 10 at an official press conference that the campaign in the east had been won. The German population believed that the soldiers could be home before winter. During the Wehrmacht's advance, some 12 million civilians fled the contested areas for the Soviet hinterland. When the Moscow population was first officially informed of the German threat on October 10, a panic broke out in the capital, with crowds of people trying to escape eastward by train or car. Stalin had these riots brutally suppressed with the help of NKVD barricade units, killing many Muscovites.

But in the same month the heavy autumn rains of the Rasputitsa set in, so that almost all roads and paths were softened in the muddy season, and thus were almost impossible to pass for wheeled vehicles and difficult even for tracked vehicles; the German offensive literally got stuck in the mud and could be resumed only after the ground froze. However, precipitation levels, and thus mud, remained below normal averages. The average precipitation for October was 51 mm compared to other 59 mm, and in November even only 13 mm compared to 45 mm.

Battle before Moscow

→ Main article: Battle of Moscow

On October 16 in Moscow, the Politburo, government offices and almost all diplomats were evacuated to Kuybyshev, and one million people left the threatened capital. Over 100,000 new soldiers were recruited and 500,000 men and women were committed to entrenchment work. Stalin himself decided to stay in Moscow.

On October 20, Army Group Center under the command of Fedor von Bock again emerged victorious from the twin battles of Vyazma and Bryansk, allowing it to continue its advance toward Moscow. However, this advance was considerably stalled, as the Army Group's main supply line, the Vyazma-Moscow highway, was constantly interrupted by Soviet explosive charges with timed fuses. These charges ruptured craters 10 meters deep and 30 meters wide and were set so that several blasts occurred each day, each one completely blocking the highway.

The Luftwaffe now began bombing strategic targets in the Moscow area, especially railroad facilities, with the aim of stopping the movement of troops and industries to the east. In defiance of this, on November 6, on the eve of the celebration of the 24th anniversary of the October Revolution, a people's meeting was held in a Moscow metro station, where Stalin appealed to the patriotism of the Moscow population. After the military parade the next morning on Red Square, the participating units marched directly to the front.

According to Dmitri Volkogonov, on November 17, 1941, Stalin issued Order No. 0428 ("Torchmen Order"): according to it, "all points of settlement where German troops are located were to be destroyed and set on fire for a distance of 40 to 60 kilometers from the main battle line into the depths ..." (see also Scorched Earth War Tactics). "For the destruction of the settlement points", "for setting fire to and blowing up the settlement points", i.e. the villages, air force, artillery and fighter commandos were to be used. Volkogonov describes how in this way countless villages were destroyed by the own army. Other villages were set on fire by the German invaders to punish Soviet partisan actions. Their inhabitants were often deported for Nazi forced labor or murdered.

Frost set in in mid-November, freezing the roads and making them passable again. Meanwhile, the German advance on Moscow stalled in the face of massive Soviet opposition. Then on December 5, under General Zhukov, a Soviet counteroffensive began with fresh units from Siberia and Central Asia. This reinforcement was made possible, among other things, by the well-known radio message of Dr. Richard Sorge, a correspondent of the Frankfurter Zeitung who worked as an agent in Japan. In it, he informed in mid-August 1941 that the Japanese Crown Council had decided not to launch (another) attack against Soviet territory from the puppet state of Manchukuo - in Manchuria. The role of the Siberian divisions is often overstated. On October 1, 1941, there were 123 rifle divisions in reserve, of which only 25 were in Siberia.

On December 7, 1941, Japan invaded the United States - without a prior declaration of war - by attacking Pearl Harbor, thus entering World War II. At the same time, low temperatures down to -35 °C caused rifles and guns to jam on the German side, engine oil and gasoline to thicken, and many soldiers' limbs to freeze to death, as early and proper winter equipment and its timely replenishment were omitted in favor of general supplies for the further advance. Since the German leadership had not anticipated that the war would last more than a few weeks, the troops were inadequately prepared for the Russian winter. German air force operations, which had become indispensable in both direct air-to-ground support and transportation, came to a virtual standstill due to the extreme winter conditions. As a result, the prospects of success for long-range ground offensives were greatly diminished.

By mid-December 1941, the danger of the Germans encircling Moscow had finally been averted. After Hitler declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941, in the midst of the Soviet counteroffensive, the war developed into a global confrontation. On December 16, British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden visited Stalin in Moscow to prepare with him the draft of a British-Soviet military agreement.

In the Moscow offensive operation (December 5, 1941-January 7, 1942), the Red Army advanced as far as 250 kilometers westward on a front about 1000 kilometers wide.

The failure in the Battle of Moscow was followed by a wave of dismissals among the commanders of the Wehrmacht. Hitler looked for culprits (or scapegoats); he dismissed von Brauchitsch after the latter had tendered his resignation several times, and from then on took over the supreme command of the army himself. Field Marshals General Gerd von Rundstedt, Fedor von Bock, and Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb were relieved of their command; some of them were later given new official duties. The "tank weapons specialist" Colonel General Heinz Guderian (Panzer Group 2, from November 2nd Panzer Army) was relieved of his front-line command and transferred to the Führer Reserve until further notice. Colonel General Erich Hoepner (Panzer Group 4, from December 4th Panzer Army) was demoted and additionally "humiliated [...] by Hitler even expelling him from the Wehrmacht." In addition, 35 corps and division commanders were relieved almost simultaneously.

According to historian David M. Glantz, the greatest mistake of German reconnaissance was underestimating the Soviet ability to restore shattered units and create new ones from scratch. He estimates this as a major reason for the failure of Operation Barbarossa. By December 31, 1941, the Soviet Union fielded 800 units at division strength. By December, the Soviet Union was able to raise 45 new armies. The experienced staffs of destroyed units formed the nucleus for the creation of the new units. This more than compensated for the loss of 20 armies destroyed by the Wehrmacht in 1941. Even before the war, Soviet planning assumed that all units would have to be completely replaced after four to eight months of heavy fighting. Invisible to outside observers, the Red Army had trained 14 million reservists for this purpose.

Soviet Winter Offensive

The German defeat before Moscow marked a turning point. The Red Army had reorganized and was now able to resist more and more efficiently. War production was moved behind the Urals, out of reach of the German air force. New soldiers arrived from the far reaches of the Soviet Union, and the new T-34 tank was produced in far greater quantities than the German tank models.

During the fighting before Moscow, urgently needed materiel and tanks were held back in Reich territory, because on Hitler's orders eight fast divisions in the west were to be made "fit for the tropics" instead: The intention was to attack the Middle East via the Caucasus. In the elation of German victories, it had even been originally assumed that there would be an "expeditionary army" on the scale of some 30 motorized divisions and panzer divisions. These units were lacking on the Eastern Front.

Moreover, contrary to what the German propaganda proclaimed, the German troops were completely inadequately equipped for the winter, since Hitler and the generals had believed in a quick campaign and believed that the Soviet Union would be defeated within a few weeks or months. As a result, the soldiers wore summer uniforms that were far too thin; the winter gear that was available was only suitable for Central Europe. In the German Reich, a fur and wool collection was conducted for the benefit of the troops. During 1942, new directives on winter warfare were issued for the second winter of the Eastern campaign.

Many divisions of the Wehrmacht had been severely decimated in the constant fighting with the Red Army, because the victories of the first months of the war had been bought with very high losses. Many weapons and other equipment had failed after weeks of marches and battles. Supplies and replacements for the overlong fronts were inadequate. In this situation came the onset of winter; and the Soviet Union was constantly throwing into battle new fighters who were rested and trained in winter warfare and also had short distances to their supply bases.

The long battles for Rostov-on-Don, which the Germans first took on November 21, 1941, but were forced to evacuate on November 29, 1941, after which it took until July 24, 1942, to retake the city in heavy fighting, acted like a prelude to Stalingrad. Also in the north of the front, an ambitious German advance, originally aimed at establishing a link with the Finns east of Lake Ladoga, was repulsed in the Battle of Tikhvin. For the victorious German leadership, the Soviet counteroffensive came as a surprise. Wilhelm Keitel admitted in his interrogation by Soviet officers that the Soviet attack "came completely unexpectedly to the High Command" and that they had "grossly miscalculated the Red Army's reserves."

The Soviet attack led to a retreat of German troops and signs of disintegration that approximated the retreat of the Grande Armée in the Russian campaign of 1812. Guderian opined, "All we really have left are armed hawsers slowly trundling back." For General Gotthard Heinrici, "the retreat in snow and ice" was "absolutely Napoleonic in nature. "As late as December 8, 1941, Hitler had ordered the "transition to defense" in his "Directive No. 39" in order, among other things, to provide "the greatest possible rest and refreshment" for the Eastern Army. On December 16, Hitler issued a halting order forbidding any rearward movement without his express permission, fearing that the entire front might fall apart. By demanding "fanatical resistance" from the battered troops and using Luftwaffe transport units to resupply cut-off sections, regardless of heavy losses, Hitler was actually able to stabilize the fragile front. In the opinion of many military historians, this order was nevertheless a serious mistake, because on the one hand it encouraged Hitler in the fatal mistaken belief that he could stabilize any front by holding orders if necessary, and on the other hand German losses were much higher in this way than they would have been in the case of a flexible defense with tactical retreats to favorable defensive positions.

By the end of 1941, however, the Wehrmacht had been pushed far back, especially in the central section of the front, and the front had been torn open in several places. Among other things, a large frontal arc formed around Rzhev and, a little later, the Demyansk encirclement; to stabilize the front, units had to be transferred here from the west and reserves mobilized. A conquest of Moscow was now out of the question. The Wehrmacht had thus lost the first major battle in the east; today, historical research refers to this as the "turn of the war in front of Moscow".