Eastern Front (World War I)

Major Military Operations on the Eastern Front

(1914-1918)

1914East Prussian

operation (Stallupönen, Gumbinnen, Tannenberg, Masurian Lakes) - Galicia (Kraśnik, Komarów, Gnila Lipa, Lemberg, Rawa Ruska) - Przemyśl - Vistula - Kraków - Łódź - Limanowa-Lapanow - Carpathians

1915Humin

- Masuria - Zwinin - Przasnysz - Gorlice-Tarnów - Bug Offensive - Narew Offensive - Great Retreat - Novogeorgievsk - Rovno - Svenziany Offensive

1916Lake Narach

- Brussilov Offensive - Baranovichi Offensive

1917Aa

- Kerensky Offensive (Zborów) - Tarnopol Offensive - Riga - Albion Enterprise

1918Operation

fist punch

The Eastern Front was the main theatre of warfare between the Central Powers Germany and Austria-Hungary and Russia during the First World War. The war zone encompassed large parts of Eastern Europe and, after Romania's entry into the war in 1916, finally stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea. In contrast to the almost static war of positions on the Western Front, there were major shifts of the front in the middle phase of the war. This was due, among other things, to the fact that the geographical location of the Eastern Front made it easier for the Central Powers to exchange troops with other theaters of war (see: Inner Line).

However, German support for the revolutionary Bolsheviks under Lenin, who took power in Russia in the October Revolution of 1917, had a decisive effect. Strong pressure from the Central Powers finally forced revolutionary Soviet Russia into the separate peace of Brest-Litovsk of March 1918, bought above all by the surrender of the economically important Ukraine. However, this advantage for the Central Powers did not affect the outcome of the war, mainly due to the entry of the United States into the war in the meantime. The dissolution of the multi-ethnic states of Russia and Austria-Hungary and the formation of new nation states in the wake of the war represented an epochal turning point in the history of Europe.

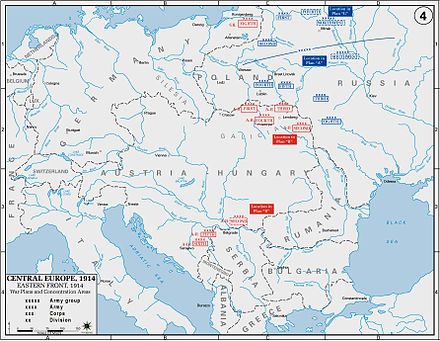

War plans and overview of the year 1914

Initial situation in the German Reich

Pre-war planning

Since 1905 at the latest (cf. Schlieffen Plan), the German General Staff had assumed that a major European war would in any case be waged simultaneously against France and Russia (cf. Two-Front War). The danger of being forced from the outset into a two-front war that would fragment and exhaust one's own forces was to be countered by means of a rapid decision in the West, enforced by an almost complete concentration of the army against France. Only afterwards was active warfare against Russia planned. Until then, weak covering forces were to defend the Prussian eastern provinces as far as possible, whereby, in the worst case, a retreat to the line upper Oder-fortress Posen-lower Vistula was considered justifiable.

The plan for a "great eastward march" that presupposed neutrality or at least passivity on the part of France was still updated year after year after 1905, but on Moltke's instructions it was shelved altogether in April 1913. Thus the German military leadership - without regard to diplomatic contingencies of initiating and triggering a major war - had committed itself to a single war plan that gave every conceivable conflict a continental dimension from the outset.

The question of a war against Russia played a far greater role in the calculations of the civilian Reich leadership for reasons of foreign and domestic policy than it did in the deliberations of the military leaders, who were fixated on France and ultimately even advised against a declaration of war against Russia. Apart from the fact that the circle around Bethmann Hollweg regarded Russia as the greater threat to Germany's position of power in Europe anyway, the Reich Chancellor's main concern in the July crisis was to find a diplomatically viable safeguard for Germany's offensive action in the West and to make it more difficult, or at best to prevent Britain from entering the war. To achieve this, however, Russia had to be manoeuvred into the position of the aggressor, i.e. the war had to come "from the East", as the Chancellor had already remarked to Kurt Riezler on 8 July. Gottlieb von Jagow outlined the logic that led to the German declaration of war on Russia on August 1, 1914 - after the Russian government had mobilized but "had not done the German government the favor of starting the war" - in a letter to an employee of the Reich Archives in 1926 as follows:

"The task of the Political Directorate, accordingly, was to initiate and justify this warlike action, and to do so in such a way as to make us appear as the 'attacked,' the aggressor being Russia. With France we had no quarrel. (...) But with Belgium there was no conflict at all; the intended violation of neutrality by this country could only be motivated by the war with France, and this in turn only by the war with Russia. Russia's action was therefore the sole basis on which action - even towards the West - could be justified. (...) The invasion of Belgium could only be justified by the war with France, and this only by the war with Russia. If there was no war with Russia, there was no reason at all for us to go to war in the West."

Moreover, Bethmann Hollweg also considered war with Russia desirable out of consideration for the Social Democracy's supporters: a war of aggression in the West without a simultaneous "defensive war" against "reactionary tsarism" would, he believed, be impossible to convey to them; severe internal tensions would inevitably be the result in such a case. Albert Ballin, who asked the Reich Chancellor a few hours before sending the declaration of war to Russia the reason for his haste in this matter ("I must have my declaration of war on Russia at once!"), received from Bethmann Hollweg in reply: "Otherwise I won't get the Social Democrats."

War aims

The purposes to be pursued in the war against Russia were determined in the course of lengthy complex disputes in which, in addition to the civilian Reich leadership, the OHL as well as private and political interest groups were intensively involved. Even within otherwise socially and politically homogeneous milieus, diametrically opposed positions were sometimes taken: Thus, exposed representatives of the East German nobility within the framework of the All-German Association and the Fatherland Party were committed to an extreme annexation program, which, among other things, envisaged the annexation of the Russian Baltic governorates to the Kingdom of Prussia, while a notable part of the Moravian, Pomeranian, and East Prussian nobility from the very beginning spoke out quite clearly in favor of a compromise peace, the sparing of the Russian "class comrades," and the restoration of the German-Russian relations of the nineteenth century, which were "good in its sense." Although Bethmann Hollweg considered a clear weakening and "pushing back" of Russia to be desirable in principle, he also pursued more or less vigorously, at least until the summer of 1915, the idea of a separate peace in the East, which would have restored the status quo ante - apart from a few "safeguards and guarantees" that were considered enforceable. In November 1914, as well as in February and July 1915, he had the Danish King Christian X and Danish diplomats make corresponding advances in Petrograd (which, however, were thwarted by the preponderance of the Russian war party around Foreign Minister Sasonov, despite the tsar's relative open-mindedness).

Erich von Falkenhayn, too, remained - basically more emphatically than the Chancellor - an advocate of a German-Russian peace of understanding until his fall in August 1916, which he admittedly no longer considered attainable since the end of 1915. A rapidly growing and ultimately decisive group in and alongside the Foreign Office, on the other hand, had been arguing since the beginning of August 1914 for a policy that - assuming a sufficiently serious military defeat of Russia - amounted to a complete "decomposition of the Russian Empire". In addition to Gottlieb von Jagow, the protagonists in this direction were primarily the Under-Secretary of State Arthur Zimmermann, Rudolf Nadolny, who had been seconded from the Foreign Office to the Politics Section of the Deputy General Staff, the influential liberal publicist Paul Rohrbach, who was employed at the Central Office for Foreign Service and closely associated with the circle around Hans Delbrück and Friedrich Naumann, as well as the professors Theodor Schiemann and Johannes Haller.

This approach envisaged, through vigorous ideological, material and financial support for more or less pronounced nationalist, autonomist and separatist tendencies - of the Finns, Estonians, Latvians, Lithuanians, Poles, Jews, Belarusians, Ukrainians, Crimean Tatars, Cuban Cossacks and various Caucasian peoples - staging a permanent "disintegration" of Russia, which would first paralyse its war effort and then, enshrined in a peace treaty, become the basis for the construction of new statehoods modelled on Germany. Rohrbach and others also toyed in passing with the idea of a "Germanization" of the Baltic States. At Zimmermann's suggestion, the Foreign Office was also prepared, from the autumn of 1915 onwards, to promote the activities of Russian revolutionaries to a certain extent, i.e. to supplement the nationalist "decomposition" with a social "revolutionization" of Russia.

In particular, the extent of German financial support for the Bolsheviks has been the subject of (not only) scholarly debate for decades. The repeatedly asserted political and financial dependence of the Bolsheviks on German support is now considered a "myth" in the specialist literature, but has been and continues to be the subject of extensive discussion in popular science and journalistic publications - especially in the German-speaking world - even in more recent times. The "Polish question" played a prominent role in all official and public discussions of war aims in Germany until the end, and it also became the "key to understanding relations between Vienna and Berlin in the First World War".

.svg.png)

Flag of the German Reich

Initial situation in Austria-Hungary

State of the armed forces

The Austro-Hungarian military consisted, in addition to the Joint Army supplied by both parts of the empire, of the Imperial and Royal Landwehr of the Austrian half and the Imperial and Royal Honved Army of the Hungarian half. Landwehr of the Austrian half of the empire and the k.u.-Honved of the Hungarian half. This political tripartition made for a cumbersome military policy within the Danube Monarchy. The officer corps of the Joint Army and also in the Ministry of Defence were dominated by German-Austrians within the leading positions. Among the militaries of the great powers, however, the Austro-Hungarian army was the smallest. Its mobilization strength was about 1.8 to 2 million men. The officer corps had severe recruitment difficulties due to poor pay. Military spending had been reduced from 29.1% to 19.7% of the budget since 1870. The armed forces were deliberately underfunded so that only about 29% of conscripts actually had to serve in peacetime. Russia and the German Reich came here on about 40 %. France even had 86%. Quarrels within the political leadership and the officer corps also delayed modernization measures in armament and equipment.

Pre-war planning

The Dual Alliance concluded in 1879 ensured that Austria-Hungary was bound to the German Empire. Within the Austro-Hungarian leadership, however, there was definitely a discord in the relationship with Germany, as the elite of the Danube Monarchy feared tutelage by the more powerful ally. The Triple Alliance concluded in 1882 represented a formal alliance with Italy, but Austria-Hungary's relationship with Italy was so fragile that the Austrian leadership expected Italian neutrality at best. The rapprochement between Russia and the United Kingdom that took place from 1907 onwards led to the constellation of a two-front war between the Central Powers against France and England on the one side and Russia and the Kingdom of Serbia on the other.

Joint pre-war planning within the Central Powers was lacking. There were agreements between the Chiefs of Staff Moltke and Conrad, but these remained very superficial. Austria-Hungary was assigned the role of holding the position in the Balkans and against Russia for three to four weeks until the German army had defeated France. The Austrian leadership submitted to the Schlieffen plan, but the Austrian Chief of Staff, Conrad von Hötzendorff, planned to eliminate Serbia first, if possible, and then turn to Russia. In case of war with Russia, the planning of the Joint Army in Galicia foresaw to bring the A Squadron with three armies into position against Russia. A minimal Balkan group was to be brought into position against Serbia. Depending on the situation, the reserves assembled in B Squadron, which comprised one army, were to be brought to bear either immediately against Russia or first against Serbia. The Imperial and Royal Navy, which operated mainly in the Mediterranean, had prepared for war by deploying a Danube flotilla against Serbia. The Imperial and Royal General Staff had no further plans about this case, and the further strategy of the war was left to the German leadership.

The Russian side had detailed knowledge of Austria-Hungary's plans from 1907 to 1913 due to the agent activities of the Austrian Colonel Alfred Redl. However, since the plans were also continually changed from 1913 until the outbreak of war, the actual betrayal of secrets had only minor consequences. Rather, the agent's activities hindered the intelligence activities of the Danube Monarchy, since Redl's activities made it possible for the Russian side to conduct efficient counterintelligence.

k.u.k. Double eagle

Search within the encyclopedia