Eastern Bloc

![]()

This article or subsequent section is not sufficiently supported by evidence (for example, itemizations). Information without sufficient evidence may be removed soon. Please help Wikipedia by researching the information and adding good supporting evidence.

The term Eastern Bloc is a political buzzword from the time of the East-West conflict for the Soviet Union (USSR) and its satellite states, which had fallen into the Soviet sphere of power and influence after World War II. The Eastern Bloc was antagonistic to the Western world. Alternatively, the states of the Eastern Bloc were also referred to as states east of the "Iron Curtain" or the "communist camp" and - in the GDR, which itself belonged to the Eastern Bloc - as the "socialist community of states".

According to Wolfgang Leonhard, a distinction was made between two economic zones: that of the European Eastern bloc states and that of the Asian allies. The politically close-knit group was formed by a system of bilateral friendship and mutual assistance agreements between the Soviet Union and its allied states and between the latter themselves. The Eastern bloc fell apart from the opening of the Iron Curtain borders beginning in the fall of 1989, followed by the disintegration of the Soviet Union by the end of 1991.

The Eastern Bloc included the Union Republics united in the Soviet Union, the People's Republic of Poland, the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (ČSSR), the Hungarian People's Republic, the People's Republic of Bulgaria, and the People's Republic or Socialist Republic of Romania (SRR). Until the 1960s, the People's Socialist Republic of Albania was also considered an Eastern bloc country. Other countries outside Central and Eastern Europe and Northern and Central Asia were counted as part of the Eastern Bloc as long as they were under the dominant influence of the Soviet Union: the Republic of Cuba, North Vietnam (from 1976: Socialist Republic of Vietnam), the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, the Mongolian People's Republic, and the early People's Republic of China.

The European states of the Eastern Bloc joined together in the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) in 1949 and in the Warsaw Pact in 1955. In the same year, the Council decided on economic integration. The people's democracies were to form a unified economic area in which production tasks were divided among the countries. The Eastern bloc, which originally appeared monolithic, especially in the days of late Stalinism until 1953, gradually fragmented due to conflicting economic, political and ideological interests. In particular, national interests still existed. The popular uprising of June 17 (in the GDR) as well as the popular uprising in Hungary in October/November 1956 made it clear that the socialist (value) order met with more or less strong rejection in many countries and that the regimes there could only hold their ground with massive Soviet support. Some socialist countries began to pursue policies independent of the Soviet Union; China in particular increasingly resisted the Soviet claim to leadership, resulting in an open rupture in the 1960s (→ Sino-Soviet discord). In the 1980s, only the members of the Warsaw Pact were referred to collectively under the term "Eastern Bloc states." The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia is sometimes generalized as an "Eastern Bloc state," but it was an independent socialist state. It was never part of the Warsaw Pact and was not a member of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance. Yugoslavia's President Josip Broz Tito was one of the co-founders of the Non-Aligned Movement; he also pursued Titoism, his own "path to socialism" independent of the USSR.

The term "Eastern Bloc" was coined in the West. It reflected its understanding, which prevailed during the Cold War, of the group of states led by the Soviet Union as a compact formation. A uniform policy was pursued in all decisive areas, based on the pronounced dependence of the respective government of a people's republic on the leadership of the Soviet Union. Not all governments of the Eastern bloc recognized the leadership role of the CPSU, but they did recognize that of the Soviet government.

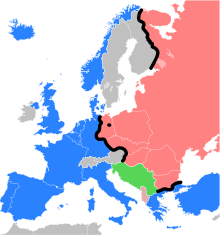

Situation around 1985: blue: member states of the Warsaw Pact; green: other temporarily socialist states under Soviet influence; light blue: socialist states that were not under the influence of the Soviet Union.

3.PNG)

The European Eastern Bloc countries. Albania is shown lighter because it was part of the Eastern Bloc only temporarily (until 1960).

The blocks in Europe: blue the West, red the Eastern bloc, Yugoslavia in between neutral white marked

History

The formation of the Eastern bloc 1945-1968

At three conferences - the Tehran Conference (November 28-December 1, 1943), the Yalta Conference (February 4-11, 1945), and the Potsdam Conference (July 17-August 2, 1945) - the anti-Hitler coalition of the Soviet Union and the Western Allies negotiated the postwar order in Europe. In the process, the Soviet Union insisted on the 1939 state borders, which were based on the 1939 treaty with the German Reich. This concerned the incorporation of the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, independent between the world wars, into the USSR as Soviet republics and also the annexation of Bessarabia. The treaty provided for the westward expansion of the Soviet republics of Belarus and Ukraine at the expense of Polish territory (→ Kresy). As a result of the Winter War, Finland had to surrender East Karelia (Karelo-Finnish Soviet Socialist Republic).

From 1945 to 1949, the Soviet Union established socialist states in all countries within its sphere of influence, such as the GDR in the eastern part of Germany. It encouraged the takeover of power by domestic communist forces, as in Poland or Czechoslovakia. As early as 1945/46, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill spoke of the Iron Curtain, which separated Europe "between the Baltic Sea and Trieste. Fundamentally, the rifts between East and West deepened after World War II in 1947, when U.S. President Harry Truman announced a new political course: The United States of America would stand by all states threatened by (Soviet) communism (Truman Doctrine/Containment Policy), and to the beleaguered European economy he offered the Marshall Plan. Josef Stalin prohibited the Eastern European countries from participating in this reconstruction program, and after the introduction of the DM in the western sectors of Berlin, the Soviet Union blocked the energy and food supply to West Berlin, whereupon the Western Allies established the Berlin Airlift. Although this blockade was lifted in 1949, the division of the world into the Western camp and the isolated Eastern bloc with its people's democracies endured.

The political climate of the people's democracies in their construction phase was characterized by collectivization and expropriation of industrial enterprises, real assets and land, arrests and deportations. A rapidly established secret police and the synchronized judiciary carried out purges with death sentences and extralegal executions. Especially in the harsh climate of the early years and with the influence of Stalinism, there were repeated internal party purges. Stalinist regimes, such as the Czechoslovak one under Klement Gottwald, sought to protect themselves from infiltration, the danger of Titoist deviation, and opportunistic partisans. Their newly acquired belt of states was of considerable importance as a cordon sanitaire and military glacis for the Soviet Union's tone-setting class, the nomenklatura of the state party. It became closely interwoven politically and increasingly "hermetically" secured along the borderline with Western Europe. In the hitherto little industrialized and predominantly agrarian states such as Poland, Hungary and Bulgaria, the Soviet Union promoted the development of heavy industry, not least in the interests of armaments and the creation of a working class. Progress in the educational, social and health care systems ultimately served the same purpose: to enable the new socialist states to assert themselves militarily through technical and industrial progress or, if necessary, to be able to provide "fraternal help" to the workers in the West who had been oppressed by capitalism during the overthrow of the system - as the facts of a just war would have to be described in real socialist terms.

Under the sign of system antagonism, a clear dividing line was drawn with countries with capitalist, market-economy social systems. The term "non-socialist economic area" (NSW) was created for "developing countries" (EL) and "capitalist industrialized countries" (KIL), whereby the latter were constantly accused of militarily aggressive intentions against the alleged "socialist world system" (SW).

Connecting elements

The Eastern bloc was held together on four levels:

- politically-ideologically through the Alliance of Communist Parties, the Communist Information Bureau (Cominform), founded in 1947;

- economically by the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA, Comecon), founded in 1949;

- militarily by the Warsaw Treaty Organization, founded in 1955;

- Strengthening hegemonic measures that should generate a common consciousness, such as the teaching of Russian as a first foreign language in school education or a coordinated sports policy.

The internal form of state or government was uniformly designed as a one-party dictatorship. Democratic elements according to Western understanding, such as freedom of the press, freedom of speech and freedom of travel, were permitted only in rudimentary form, as in the Soviet Union, in order to limit opposition and ensure cohesion. A (pseudo-)multiparty system existed only in the form of the bloc parties in some states. At all levels, the Soviet Union demanded absolute authority in the person of the General Secretary of the CPSU. This right to issue directives was not formally established, but it was applied by force when an Eastern bloc state or its citizens tried to go their own way.

The first disputes and differing views on the Soviet leadership role took place as early as 1947 between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia under Tito's leadership. This led to a break between Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union in 1948. In 1961, Albania broke with the Soviet Union and henceforth oriented itself toward Red China. Albania finally left the Warsaw Pact in September 1968, shortly after the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Soviet and other troops.

As far as possible, as in the GDR in 1953 and in Hungary in 1956, the Soviet army put down insurrectionary movements. In 1968, the emancipation of the ČSSR toward a "socialism with a human face," which had been resented for years, was brought to a violent end when troops from the Soviet Union and other Eastern bloc states marched into the country in a concerted action; since the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) had feared a spread of reform communism to the GDR, the suppression of the Prague Spring in August 1968 was defended by it. This was the first manifestation of the Brezhnev Doctrine. A similar threat arose in 1981 because of the breakaway movements in Poland, after the communist regime there had had to violently suppress protest movements on its difficult terrain (collectivization of agriculture had largely failed in Poland) as early as 1956 and 1970. In 1981, the Soviet Union was tied up in Afghanistan; in this case, reminders and threats from Moscow were enough to bring the state leadership back to the hard Soviet line for the time being in the form of a military dictatorship under Wojciech Jaruzelski. Under special conditions and in certain areas, it was possible for individual states to take a special path: Poland's consumption-oriented but debt-financed economic policy, the so-called Hungarian goulash communism after 1970.

Romania could afford to pursue a very stubborn policy. The Soviet occupation forces had been withdrawn from the country since 1958, and the population's approval of the Soviet Union, but also of the political class, was extraordinarily low. For one thing, Romania was historically and culturally aligned not with Russia but with France as well as Germany; for another, it had suffered territorial losses in Bessarabia, the Herza region, northern Bukovina, and Snake Island. The armed anti-communist resistance in Romania lasted particularly long, and it was not until 1976 that the last armed fighter was arrested.

Another reason was the Soviet Union's refusal to return the Romanian treasury. Romania historically had no significant communist movement: By the end of 1944, the Communist Party had fewer than 1,000 members. As a result, the political elite consisted either of individuals loyal to the Soviet Union who were sent to Romania from the Soviet Union (these were gradually marginalized after Stalin's death) or of native Romanians who joined the Communist Party for opportunistic reasons and had limited sympathy for the Soviet Union. Romania repeatedly broke bloc solidarity, for which the West did not fail to applaud. For example, the country had condemned military action against Czechoslovakia and refused to participate. It ignored the Eastern bloc's boycott of the 1984 Olympics, losing sight of the fact that Romania's long-time head of state and party, Nicolae Ceaușescu, who in his early years pursued a policy of opening up to the West, later developed into a bizarre despot around whom in the 1980s a personality cult was waged that was unprecedented even in the Eastern bloc.

The People's Republic of Bulgaria was considered the most loyal ally of the Soviet Union. This led to the derisive name "16th Soviet Republic." As in Romania, there was no Soviet troop contingent there. However, Bulgaria had historically and culturally a close affinity to Russia and it had a strong communist movement already in the interwar period. Bulgaria lacked the bad experiences with the Soviet Union, such as in Romania.

Cooperation between the members was not always free of tensions either. Relations between the GDR and Poland were strained in the 1980s because of the prosperity gap. On the other hand, rivalries under the banner of "fraternity" were suppressed within the pact system, such as the relationship between Romania and Hungary, which was burdened by many old border disputes and quarrels. Economically, the Soviet Union charged higher prices for raw materials and energy after 1980, which caused the allies considerable problems in industry and energy supply.

In the last years of its existence, the group of states was no longer a unified bloc in every respect. The "satellite states" were dependent on the Soviet Union to varying degrees. This affected the assertion of power by the leading cadres, the economy, and the stationing of strong contingents of Soviet Army troops in several states. Of the total 600,000-700,000 troops of the Soviet armed forces, about two-thirds were in the GDR. Until the 1980s, no decisive action by an Eastern bloc country could be taken without consulting the CPSU Central Committee.

Containment and other anti-communist reactions

During the Cold War, the West, led by the United States, attempted to contain further expansion of the communist sphere of influence, which seemed to be assuming threatening proportions, especially in Asia, after the Soviet Union had made considerable territorial gains. The U.S. countered this with the Truman Doctrine and pursued a policy of containment. On the economic level, the Marshall Plan of 1947 offered generous financial aid to Western European countries for the reconstruction of their war-torn economies. The February upheaval in Prague in 1948, the Berlin crisis in 1948/49, the "loss of China" in 1949 and even more so the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 strengthened the impression of a communist threat to the West in the long term. In the U.S. and Europe, a wave of rearmament began in the early 1950s. The two superpowers engaged in an arms race.

NATO had been the Western military alliance against the Soviet Union's threatening westward expansion since 1949. This, in turn, was followed by the formation of the Warsaw Pact in 1955. On the political level, opposition movements of the Eastern Bloc countries were supported from the West. Until their final destruction in the 1950s, the United States also strengthened armed separatist groups within the Soviet Union, for example in the Baltic states. In parallel, there were initially other concepts of breaking up the Eastern bloc through confrontation.

In the late 1940s and 1950s, communist parties were banned or hindered in their activities in many parts of Western Europe, as in the Federal Republic of Germany in 1956. However, this did not happen in some European countries. Especially in France and Italy (Eurocommunism), communist parties achieved notable shares of the vote in parliamentary elections until the 1970s. U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower's idea of pushing back communism through rollback policies was considered more of a campaign phrase. A military operation seemed too dangerous for U.S. policy in Europe. The clear nuclear strategic superiority of the USA, which still existed at the beginning, could not be converted into political capital and thus remained meaningless.

Poststalinism

In the thaw period under Nikita Khrushchev in the mid-1950s, the Eastern Bloc moved away from the doctrine that systemic conflict must necessarily culminate in war. Maintaining peaceful coexistence now took precedence. In 1954, Georgy Malenkov, a top Soviet official, had expressed concern for the first time about the possibility of nuclear war, which would be better avoided. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Soviet Union achieved a number of successes that caused consternation and amazement in the West at the capabilities of "the East": for example, the Sputnik shock of 1957 and Yuri Gagarin's space flight of 1961. In 1958, there was a new Berlin crisis, and less than a year later - on September 15, 1959 - Soviet leader Khrushchev came to the United States on a state visit.

However, the situation worsened again in the early 1960s. The bloc confrontation threatened to escalate into war. The most dangerous phase between the construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 and the Cuban Missile Crisis in the fall of 1962 was followed by a certain disillusionment on both sides with regard to possible confrontational solutions. For the first time, a real awareness of the threatening possible consequences of a military confrontation between the pact systems waged with nuclear weapons spread.

The real socialist countries managed a certain stabilization in the 1960/1970s. In the West, the rearmament associated with considerable efforts and the increased military clout of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact as a whole were noted, especially with regard to strategic nuclear weapons. In this area, the USSR was widely believed to have achieved near parity with the United States (balance of terror). Thus, the view prevailed in the West that the policy of détente offered a more appropriate means of gradually pushing back the Kremlin's sphere of power and influence. Suspiciously orthodox forces in the GDR, for example, suspected at an early stage and to a certain extent accurately that this was "aggression on felt shoes," but they were unable to offer any effective resistance to the emerging development in the long run. From the end of the 1970s, the GDR - like other Eastern bloc states - was dependent on intensified economic relations and Western support because of its ever-increasing economic difficulties. The billion-euro loan brokered by Franz Josef Strauß in 1983 (followed by a second loan in 1984) was a striking expression of this development.

Even in the days of the West German Hallstein Doctrine, the Eastern alliance, held together by the Soviet Union, was ultimately regarded as the only guarantor of the postwar borders. From this, especially in Czechoslovakia and even in Poland, it derived a not to be underestimated part of its legitimacy and an important residue of acceptance. From the beginning of the 1970s, this factor lost importance with the changed position of the Federal Republic and the concluded treaties with the East.

In the early to mid-1970s, the Eastern bloc seemed to have reached the peak of its international status. In 1975, this was demonstrated by the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, signed by the socialist states. This defined their important role in connection with the human and civil rights issue, to which the collapse of the party-communist systems of Eastern Europe was ultimately attributable.

The zone border between the political East and West respectively, the Iron Curtain, was in particular a prosperity border that can still be felt today. While the Eastern bloc experienced a slow economic decline after World War II due to a planned economy, command structures and the strong dominance of the USSR, democracy, a market economy, the founding of the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) and Marshall Plan funds led to a steady reconstruction in the West. It was precisely this creation of prosperity and attractiveness in the West, combined with its dissemination through the media via TV and radio, that then led to increasing dissatisfaction among the population in the East and flight to the West.

End of the Eastern Bloc 1985-1990

The independent trade union Solidarność, along with the Catholic Church, was the main force behind the movement that marked the end of communism in Poland. To this end, a Polish pope, John Paul II, had been in office since 1978, and he championed Polish Catholic causes through his diplomacy of visits. Mikhail Gorbachev stated in his memoirs in 1992: "Everything that has happened in Eastern Europe in recent years would not have been possible without this pope."

In March 1985, Gorbachev became General Secretary of the CPSU. He changed the course of the domination and oppression of the Soviet satellite states. Already at the funeral of Konstantin Chernenko (he had been General Secretary for 13 months), Gorbachev called the Eastern Bloc leaders together and told them what later became known as the "Sinatra Doctrine." This conceded the socialist brother countries their own path to socialism and was part of the Perestroika (Reconstruction) program. While some states increasingly broke away from the Eastern bloc by 1989, the GDR leadership tried unsuccessfully to keep it together. In addition to the emerging domestic protest movements, in the spring and summer of 1989 the previously strict isolation of Eastern Europe through the Iron Curtain was partially loosened by individual countries and then lifted. Hungary dismantled its border fortifications with Austria as of May 2, 1989. By this time, the Hungarian wire fence system with its electrical alarm devices was already completely outdated or rusty, and almost 99 percent of the alarms were false alarms, with up to 400 soldiers having to be deployed for each alarm. However, the Hungarians wanted to prevent the formation of a green border by increasing the guarding of the border or to solve the security of their western border in a cheaper and technically different way. After the dismantling of border fortifications, neither the borders were opened nor the previous strict controls were discontinued. As late as June 4, 1989, the GDR leadership publicly welcomed the violent suppression of student protests in Tiananmen Square in Beijing, which was to be understood as a threat that such a thing was also conceivable in the GDR; this later led the PRC, for its part, to offer its support by providing manpower against a bleeding out of the country during the mass exodus.

In the spring of 1989, there were army operations against demonstrations within the Soviet Union in Tbilisi and the Baltic States. It was unclear at that time whether the Soviet Union and the Eastern bloc as a whole would intervene militarily if inconvenient anti-communist and anti-Soviet developments occurred.

The opening of a border gate between Austria and Hungary at the Pan-European Picnic on August 19, 1989, which was widely imitated by the media, reinforced the trend and eventually triggered the "crisis of autumn 1989", which was historic for the Eastern Bloc. The patrons of the picnic were the initiator Otto von Habsburg and the Hungarian Minister of State Imre Pozsgay. The latter saw in the planned picnic a chance to test Gorbachev's reaction to a border opening at the Iron Curtain. As early as July 10, 1989, files of the Hungarian State Security Service noted that an event was planned at the border based on a proposal by Otto von Habsburg, and on July 31, 1989, the Hungarian Defense Against Internal Reaction informed its superiors about the preparations for the Sopron Pan-European Picnic. The Pan-European Movement had thousands of flyers distributed inviting people to a picnic near the border at Sopron. Under the motto "Dismantle and take with you!" participants were to be allowed to participate in the dismantling of the Iron Curtain. Leaflets announcing the place and time of the picnic and giving directions also circulated among GDR refugees in Budapest. Many of the GDR citizens understood the message and traveled.

At the event on August 19, 1989, 661 East Germans crossed the border from Hungary to Austria through the Iron Curtain. It was the largest ever escape movement of East Germans since the construction of the Berlin Wall. The USSR did not intervene in these events. The primary victim of the situation resulting from Soviet passivity was initially especially the SED leadership in Berlin, which then asked Moscow for (not granted) support on August 21.

The information about the opening of the border spread by the mass media triggered further events. On August 22, 1989, 240 people crossed the Austro-Hungarian border again, but this time without any preliminary arrangements with Hungarian security authorities. The attempt to repeat this action on August 23 was stopped by border guards, supported by "workers' militias", by force of arms, injuring several refugees. With the mass escape without Soviet intervention, the dams broke. East Germans came by the tens of thousands to Hungary, which was no longer willing to keep its borders tight. The GDR leadership in East Berlin reacted indecisively and did not dare to close its own country's borders. The subsequent occupations of West German embassies by GDR refugees in August 1989, together with the subsequent exit procedures, and Hungary's abandonment of border controls as of September 11, 1989, led to further uncontrolled mass escapes of GDR citizens. Without prior consultation with the GDR government, Hungary allowed all present GDR citizens willing to leave the country to pass through to the West. By the end of September, 30,000 emigrants had arrived in the Federal Republic this way.

On September 30, 1989, after negotiations with Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze and others, then-Federal Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher managed to get several thousand East Germans who had fled to the grounds of the Prague Embassy allowed to leave for the West on special trains via a detour through the GDR.

In the fall and winter of 1989, the communist leaders in all Eastern bloc countries (except the Soviet Union) lost their monopoly on power, so that the Eastern bloc fell apart. The isolation was over and the possibility was given to leave the countries in the direction of the West via the now broken Iron Curtain. The chain reaction starting from the Pan-European Picnic eroded the power of the communists in the Eastern Bloc. This caused a change in the system of government in the GDR, Poland, Hungary, the ČSSR (Velvet Revolution), Bulgaria and Romania by December 1989. The fundamental cause of popular discontent, in addition to the lack of self-determination and freedom, was the economic collapse of the unitary states. Key systemic factors of the Eastern bloc were responsible for this development:

- economic problems due to state economy,

- Indebtedness to Western Lenders,

- internal problems due to party dictatorship,

- External economic problems caused by foreclosure policies.

The USSR disintegrated in 1991, although the first referendum in the history of the Soviet Union in the spring (in which, however, some Union republics no longer participated) still produced a majority in favor of the Union's continued existence.

Border shifts after the Second World War and the formation of the Soviet zone of influence until 1948

The Iron Curtain in Europe during the Cold War. Yugoslavia and Albania were socialist countries, but from 1948 and 1961 respectively they were no longer Eastern bloc states.

Freedom to travel

Since the construction of the Wall in August 1961, travel to non-Socialist countries by GDR citizens under the age of 65 was possible only upon application and on certain occasions. Usually only if a return to the GDR was likely, for example because children or spouses did not travel with them or there were no relatives in the West. Starting in 1964, all retirees were allowed to visit relatives in the West once a year, and later there were further travel concessions.

This was regulated similarly in other Eastern bloc countries. Thus, citizens from the ČSSR, the Hungarian People's Republic and the People's Republic of Bulgaria were already allowed to leave the country for Western Europe in the early 1970s for justified reasons, such as study trips.

In Hungary, it was already possible to make private trips against payment of foreign currency at the beginning of the 1980s. Hungary introduced general freedom of travel for its citizens in early 1988. There were also tighter travel restrictions, as in Romania or the Soviet Union.

Citizens of the SFR Yugoslavia were more privileged as citizens of a socialist but non-aligned state, since it did not belong to any military bloc. Travel to Yugoslavia was no more complicated for Western Europeans than to Italy or France; in particular, Yugoslavs benefited from foreign exchange-earning Western tourists, millions of whom came to the Adriatic coast every year. Yugoslavia was the only socialist country whose citizens could leave without visas for Western Europe, North America and other parts of the world. As early as the 1960s, laborers from Yugoslavia, known as guest workers, began arriving in Germany, Austria and Switzerland in the course of freedom of movement regulations.

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Eastern Bloc?

A: The Eastern Bloc was a group of former Communist states in Central and Eastern Europe, including the countries of the Warsaw Pact, along with Yugoslavia and Albania. They were Soviet satellite states that had been controlled by the Axis countries during World War II and were subject to extensive political and media controls by Joseph Stalin.

Q: What was COMECON?

A: COMECON (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance) was an economic cooperation organization among members of the Eastern Bloc. It was established in 1947 by Joseph Stalin to arrange economic cooperation between member countries.

Q: How did events such as the split of Josip Broz Tito affect control over the bloc?

A: Events such as the split of Josip Broz Tito prompted stricter control over the Eastern Bloc, as it demonstrated that certain oppositional factions could revolt against Soviet rule. This led to increased restrictions on emigration from these countries.

Q: What happened in 1989 that caused dissolution of the bloc?

A: In 1989, counterrevolutions throughout much of the bloc dissolved it due to Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika reforms which had caused inefficiencies and stagnation throughout much of its existence prior to its dissolution.

Q: How do people feel about life after 1989 when free markets became dominant?

A: According to a 2009 Pew Research Center poll, 72% of Hungarians, 62% Ukrainians and Bulgarians felt their lives were worse off after 1989 when free markets became dominant. However, follow-up polls showed that 45% Lithuanians, 42% Russians and 34% Ukrainians approved this change.

Search within the encyclopedia