East India Company

![]()

East India Company is a redirect to this article. For the darknet market, see East India Company (darknet market).

The British East India Company (BEIC), until 1707 English East India Company (EIC), was a merchant Indian trading company that existed from 1600 to 1874 and rose to become the dominant power in India after defeating the Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, establishing nearly 200 years of British colonial rule over the country.

The BEIC came into being as the first of several European East India Companies when Queen Elizabeth I issued a privilege to a group of wealthy London merchants on 31 December 1600. This granted the Governors and Company of merchants of London trading to the East-Indies the right to transact all English trade between the Cape of Good Hope in the west and the Straits of Magellan in the east, i.e. in the entire area of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, for a period of 15 years. It was given a seal, could elect its own governor and 24 directors, and was allowed to make its own corporate laws ("by-laws").

Initially, the company equipped five ships with 72,000 pounds sterling, which, under the leadership of Captain James Lancaster, landed at Aceh on Sumatra on 5 June 1602. Further expeditions of this kind followed in 1604 and 1610. An envoy to the Great Mogul Jahangir obtained the right to establish trading stations on the west coast of the Near East. This right, however, the company could not exercise until after the victory over the reluctant Portuguese in 1612. It was not able to gain a foothold in Madras and Hugli until 1640, where it encountered opposition from the rival Dutch East India Company (VOC).

Charles II confirmed the earlier privileges on April 3, 1661, and also granted the Company civil jurisdiction, military power, and the right to make war and peace with the "infidels" in India. In addition, he enfeoffed the Company with the city of Bombay, which he had received as a dowry from his Portuguese wife Catherine. Charles's successor, James II, granted it the right to build forts, raise troops and strike coins to put it on an equal footing with the VOC. In 1694 the privileges were reaffirmed, but only amid great protests in the London Parliament by the merchant class, which had been excluded from the monopoly. The Company's oppressive domination practices in its Indian possessions also met with increasing criticism. In 1698, the English government therefore granted a rival company the same rights as the Company of Merchants. The latter was therefore forced to merge with its competitor in 1708 to form the "United East-India Company". Thereafter, the Company's business flourished to an unprecedented extent. It visibly gained influence on the political situation in India and, after Plassy in 1757, became its dominant factor.

The administration during this period was divided into the Bengal Presidency, the Bombay Presidency and the Madras Presidency. Warren Hastings was appointed Governor General of the East Indies for the first time in 1773.

It was not until 1784 that the India Act of the Pitt government placed the Company under the supervision of a government controlling authority. This acted as a ministerial department and supervised the employment of the Company's higher officials, judges and army commanders. In commercial matters, however, the BEIC for the time being retained its old independence. In 1813 it lost its special rights to trade, but retained supreme authority in civic and military affairs. Increasing insurrections, the last of which was that of the Sipahi in 1857, led the British Parliament to transfer the Company's rights to the Crown by the Government of India Act of 2 August 1858. The last meeting of the directors was held on 30 August 1858. It was finally dissolved in 1874.

Heraldic side of the X-cash coin, East India Company, year 1808

Value side X-cash coin of the East India Company from 1808

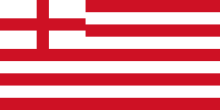

The flag of the English East India Company 1600-1707

.svg.png)

Flag 1707-1801 The number of stripes varies in historical accounts, the 13 stripe form did not appear until after the creation of the Province of Georgia in 1732

.svg.png)

Flag 1801-1858

Meaning

From its headquarters in Leadenhall Street, London, it organized the establishment of the British colony of India. In 1718, the Company obtained an imperial decree from the Mughal Emperor in India exempting it from paying customs duties in Bengal. This gave it a significant advantage over its competitors. A decisive victory by Sir Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive at the Battle of Plassey in 1757 also made the British East India Company a military powerhouse. By 1760, the French had been largely driven out of India. Only on the coast remained some French trading settlements, so also Pondicherry.

The Company also had interests along the routes from Britain to India. As early as 1620, the Company attempted to claim the area around Table Mountain in what is now South Africa. Later it occupied and ruled St Helena. Similarly, it established branches in Hong Kong and Singapore. The company hired William Kidd to fight piracy. Likewise, it expanded tea production in India. Another memorable event in the Company's history was the guarding of the prisoner Napoleon Bonaparte on St. Helena. Also, their goods formed the subject of the Boston Tea Party in the colony of America.

The flag of the British East India Company is said to have served as a template for the US Stars and Stripes flag. The British flag dates back to the founding years in the 17th century, Stars and Stripes was created in 1777.

The shipyards of the East India Company served as a model for those in St Petersburg, parts of their administration have survived in the Indian bureaucracy, and their corporate structure was the most successful model of a joint stock company.

Tribute demands by Company managers to the Bengal Treasury contributed to the great famine of 1770 to 1773, which claimed millions of lives.

History

The founding years

The company was incorporated as The Governor and Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies by a group of enterprising and influential businessmen who obtained a royal charter with an exclusive right (monopoly) of the India trade for a period of 15 years. The company had 125 shareholders and a share capital of £72,000. Initially, however, it could hardly shake the Dutch control over the spice trade. Nor did it initially succeed in establishing a permanent base in India. Eventually her ships reached India and docked at Surat. A trading post was then also established there in 1608. In the next two years she was able to establish her first trading post at Machilipatnam on the Coromandel Coast in the Bay of Bengal. The high profits reported by the company in India prompted King James I to grant licenses to other British trading companies. However, in 1609 he renewed the Company's charter for an indefinite period, with the proviso that the charter would expire after three consecutive years without profits. Negotiations with the Dutch East India Company about a merger of the two companies failed in 1615.

Subsidiaries in India

Their merchants were frequently involved in clashes with their Dutch competitors in the Indian Ocean. Perhaps seeing the futility of trade wars in distant waters, the British in any case decided to explore possibilities of a permanent settlement on the Indian mainland. One prompted the British government to begin a diplomatic initiative. In 1615, Sir Thomas Roe was commissioned by James I to seek out the Mughal emperor Jahangir, who ruled 70 percent of the subcontinent. The purpose of this mission was to conclude a trade agreement that would give the British East India Company exclusive rights to settle in Surat and other areas and to set up counting houses. In return, the Company offered to supply the Emperor with goods and luxuries from Europe. The mission was exceedingly successful, and Jahangir conveyed a letter to James I, writing:

"Upon the assurance of your royal love, I have given general orders to all the kingdoms and ports of my dominions to receive all the merchants of the English nation as the subjects of my friend; that wheresoever they choose to dwell, they shall enjoy perfect liberty without restraint; and wheresoever they shall arrive, neither Portugal nor any other shall dare to disturb their tranquillity; and wheresoever settled, I have directed my governors and captains to grant them such liberty as they may desire for themselves; to sell, buy, and transport into their country as they may choose.

In confirmation of our love and friendship, I desire your Majesty to command her merchants to carry in her ships all kinds of luxuries and splendid wares worthy of my palace; and that you will send me your royal letters on every occasion, that I may enjoy your health and successful affairs; that our friendship may be mutual and everlasting."

The path to a perfect monopoly

Expansion

With such support, the Company soon succeeded in surpassing the Portuguese, who had established branches in Goa and Bombay. It succeeded in establishing branches in Surat (account founded in 1612), Madras (1639), Bombay (1668) and Calcutta. By 1647, the company had 23 offices and 90 employees in India. The main forts became Fort William in Bengal, Fort St George in Madras and Bombay Castle. In 1634, the Mughal Emperor extended hospitality to English merchants in the Bengal region (and in 1717, one of his successors exempted them completely from customs duties on goods). The Company's core business was now cotton, silk, indigo dye, saltpetre and tea. Throughout, it sought to penetrate the Dutch spice monopoly in the Straits of Malacca. In 1711, the Company established a trading post in Canton, China, to purchase tea with silver; this was the beginning of the British China trade. In 1657 Oliver Cromwell renewed the charter of 1609, and instigated minor changes in the Company's ownership structure.

The Company's position was elevated by the restoration of the monarchy in Britain. By a succession of 5 legislative enactments around 1670, King Charles II endowed them with the rights to independently acquire territory, coin money, command forts and troops, enter into alliances, declare war, make peace, and exercise both civil and criminal jurisdiction in the acquired territories. The Company, surrounded by trade rivals, other imperial powers, and at times hostile native rulers, had a growing need for military protection. Therefore, the freedom to manage its own military affairs was a welcome gift, and the Company quickly established its own armed forces from 1680, recruiting mainly from the native population. Thus, it is debatable whether the Company constituted a state on the Indian mainland from 1689, since it was largely sovereign. It administered the vast territories of Bengal, Madras and Bombay and had considerable military clout.

Trade monopoly

Since some of the company's employees were rich, they were able to return home. Thus, the doors to power were then open to them. As a result, the company developed its own lobby in parliament. Despite all this, it came under pressure from ambitious businessmen and former partners of the Company (disparagingly called interlocutors by the Company) who also wanted to establish private trading companies in India. This led to the passing of a Deregulation Act in 1694, which allowed any English company to trade with India unless specifically prohibited by an Act of Parliament. This repealed the charter that had been in force for nearly 100 years. An Act of 1698 created a new "parallel" East India Company (officially called the English Company Trading to the East Indies), which had a government guarantee of £2 million. However, the powerful shareholders of the old company soon acquired shares in the new concern for £315,000 and came to dominate the company. For a time the two companies competed for market share in both England and India. It soon became clear, however, that the original company felt little measurable competition. The two companies merged in 1702 under a tripartite agreement between the government and the two companies. According to this agreement, the merged company loaned the Treasury a sum of £3,200,000 in return for exclusive trading rights for three years - after which the situation was to be reassessed. The merged company became the United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies.

In the decades that followed, a back-and-forth developed between the East India Company lobby and Parliament. The Company sought to establish its privileges permanently, while Parliament would not voluntarily give up the ability to siphon off the Company's profits. In 1712, an act renewed the Company's status, but its debts were repaid. In 1720, 15% of British imports came from India, and almost all of these were transacted through the East India Company. This increased the influence of their lobby. In 1730 a new Act extended the licence until 1766.

At this time Britain and France became bitter rivals, and there were frequent skirmishes between them for control of their colonial acquisitions. In 1742 the British government, fearing the financial implications of war, agreed to extend the East India Company's trade monopoly with India until 1783. In return it received a further loan of one million pounds. The engagements resulted in the feared war, and between 1756 and 1763 the Seven Years' War directed the attention of the state to the strengthening and defense of its territories in Europe and North America. The war also took place on the Indian subcontinent, between the forces of the East India Company and French forces. Around the same time, Britain was gaining an edge over its European rivals with the arrival of the Industrial Revolution. The demand for Indian raw materials was driven by the needs of the economy and to maintain troops in times of war. As the starting point of the Industrial Revolution, Britain experienced a higher standard of living and this cycle of wealth, demand and production had a profound effect on overseas trade. The East India Company became the largest single participant in British world trade, reserving for itself an unassailable position in government decision-making.

Colonial Monopoly

The war ended with the defeat of French forces and limited French imperial ambitions. The defeat also limited the influence of the Industrial Revolution in French territories. General Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive led the East India Company to a remarkable victory against Joseph François Dupleix, the commander of the French in India, and recaptured Fort St. George from them. By the Treaty of Paris (1763), the French were forced to conduct their trade through small enclaves in Pondicherry, Mahé, Karaikal, Yanam, and Chandernagor without a military presence. Although these small outposts remained in French possession for two centuries, French ambitions for Indian territories were de facto buried. The East India Company was thus spared a major potential competitor. In contrast, after this victory and with the backing of its army, the East India Company was able to further expand its influence.

Local resistance

However, the East India Company continued to experience opposition from native rulers. Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive led the Company forces to victory against Siraj-ud-Daula, who had French support, at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Through this he eliminated the last significant resistance in Bengal. This victory alienated the British and the Mughal emperors, to whom Siraj had served as an autonomous ruler. But the Mughal Empire was already in decline after the death of Aurangzeb and subsequently broke into pieces and enclaves. After the Battle of Baksar, the emperor, Shah Alam, who now ruled only formally, handed over administrative rights over Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. Thus, Clive became the first British governor of Bengal. Haidar Ali and Tipu Sultan, the legendary rulers of Mysore, made life difficult for the British. They had allied with the French and continued their fight against the Company with the four wars of Mysore. Mysore was finally captured by the British in 1799. In the process, Tipu was slain. With the gradual loss of power of the Marath Empire in the aftermath of the war with the British, they secured Bombay and its environs. It was in these campaigns that Arthur Wellesley, later Duke of Wellington, first demonstrated his skills, which eventually led to his victory in Spain and at the Battle of Waterloo. A particularly notable clash of forces under his command was the Battle of Assaye. With this, the British secured all of southern India (with the exception of French enclaves and some native rulers), western India, and eastern India. The last vestiges of local administration were confined to the northern regions around Delhi, Avadh, Rajputana and Punjab, where the Company's presence continued to expand amid local strife and dubious offers of protection from the Company. In 1848, after the First and Second Sikh Wars, Punjab was also annexed to the Company's territory. Threats and diplomacy prevented the native rulers from ganging up against the Company. In the hundred years between the victory at the Battle of Plassey and the Great Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Company evolved more and more from a trading company into a state.

Regulation of the affairs of the East India Company

Financial difficulties

Although the East India Company became increasingly brutal and ambitious in its subjugation of recalcitrant states, it became more apparent by the day that the Company was incapable of managing the vast newly acquired territories. The famine of Bengal, which killed one-sixth of the native population, set alarm bells ringing at home. Expenditure on military and administration in Bengal rose steeply because of the decline in productivity. At the same time, economic stagnation and depression prevailed throughout Europe, triggered by the aftermath of the Industrial Revolution. Britain faced rebellion in North America (a major importer of tea), and France was on the verge of revolution. The directors of the East India Company attempted to avert bankruptcy by appealing to Parliament. In this they asked for financial assistance. As a result, the Tea Act of 1773 was enacted, granting the Company greater autonomy to manage its trade in North America. However, due to the monopolistic activities, the Boston Tea Party was triggered. This was one of the major events that later led to the American War of Independence.

Regulatory Act of 1773

After the United States gained independence from Britain, the focus of the British shifted to the other side of the globe to India. The armies destined for India as well as those of the East India Company grew, and with them the cost of operation. The Company was forced by the Regulating Act for India in 1773 to undergo a succession of administrative and economic reforms. Despite stubborn opposition from the East India lobby in Parliament and by the Company's shareholders, the Act was passed. It introduced significant controls by the government and allowed land to be formally placed under the control of the Crown but thereafter surrendered to the East India Company on a two-year lease of £40,000. Under these terms the Governor of Bengal Warren Hastings was promoted to the rank of Governor-General. Under his authority was the administration of the whole of British India. These provided that his nomination in future should be by a council of four, appointed by the crown. He was given power over war and peace. British lawyers were also to be sent to India to ensure the application of British law. The Governor-General and the Council thus had complete legislative powers. Thus Warren Hastings became the first Governor-General of India. The East India Company was allowed to retain its monopoly of trade. In return, it had to pay a sum to the Crown every two years and undertake to export a minimum of goods to Britain. Administrative costs also had to be met by the Company. However, these terms, initially welcomed by the Company, had a negative aftermath: annual burdens were imposed on the Company and its financial situation continued to deteriorate.

Decline of the East India Company

In the meantime, Hastings fell out of favor with the Council of Four. The Council returned to Britain and instituted proceedings against him for corruption, which eventually led to his removal. The Regulating Act was considered a failure, as it was immediately clear that the delineation of powers between the government and the Company was highly uncertain and a matter of interpretation. The government also felt obliged to heed humanitarian petitions seeking better treatment for native populations in British-occupied territories. Edmund Burke, a former East India Company shareholder and diplomat felt compelled to alleviate the situation by introducing an India Bill 1783. However, the bill was defeated due to intense lobbying by the East India Company and allegations of nepotism in the appointment of councillors. Despite all this, this Act was an important step towards pushing back the East India Company, and in the India Act of 1784 the conflict was peacefully settled. In this the control of government and trade was neatly demarcated between the Crown and the Company. After this turning point, the Company functioned as a regulated subsidiary of the Crown, and the Company extended its influence into neighboring territories through coercion and threats. By the mid-19th century, the Company's rule extended over much of India, Burma, Singapore, and Hong Kong, with about 20% of the world's population under its control.

The British sphere of influence continued to expand; in 1845 the Danish colony of Tranquebar was acquired by Britain. The Company had on various occasions extended its influence in China, the Philippines and Java. In the process, the Company remedied its critical shortage of cash to purchase tea by exporting Indian-made opium to China. China's efforts to stop this trade led to the First Opium War with Britain.

The end

The Company's efforts to administer India served as a model for British civil administration, especially in the 19th century. After the Company lost its trading monopoly in 1833, it reverted to being a purely trading company. In 1858, the Company lost its administrative role to the British government after its Indian soldiers mutinied (Indian Rebellion of 1857).

This was done with the Government of India Act 1858, passed by the British Parliament on August 2, 1858 under Palmerston's influence. The key points of the Act were:

- the takeover of all territories in India from the East India Company, which at the same time lost the powers and control hitherto vested in it.

- the government of the possessions in the name of Queen Victoria as a crown colony. A Secretary of State for India was placed at the head of the official administration.

- the assumption of all the assets of the Company and the entry of the Crown into all contracts and agreements previously entered into.

British India then became a formal crown colony. In the years that followed, the Company's holdings were nationalised by the Crown. The Company still managed the tea trade on behalf of the government, especially to St Helena.

The East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act dissolved the company on January 1, 1874. The Times reported:

It achieved a work which, as such, had never before been attempted by any other enterprise in the history of mankind, and which, as such, is not likely to be repeated in the future.

Mughal Empire around 1700

Search within the encyclopedia