Dutch East India Company

The Dutch East India Company (Dutch: Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie; Vereenigde Geoctroyeerde Oostindische Compagnie, abbreviated VOC or Compagnie for short) was an East India company formed on 20 March 1602 by Dutch merchant companies to eliminate competition among themselves. The VOC was granted trading monopolies by the Dutch state, as well as sovereign rights in land acquisition, warfare and fortification. It was one of the largest trading companies of the 17th and 18th centuries.

The VOC had its headquarters in Amsterdam and Middelburg. The merchant shipping headquarters were located in Batavia, today's Indonesian capital Jakarta on Java. Other branches were established on other islands in what is now Indonesia. A trading post was also located on Deshima, an artificial island off the coast of the Japanese city of Nagasaki, and others in Persia, Bengal, now part of Bangladesh and India, Ceylon, Formosa, Cape Town and South India.

The VOC's economic strength was based primarily on its control of the spice route from the back of India to Europe, thereby dominating part of the lucrative Indian trade. Structured in six chambers (camers), it was the first to issue shares. After the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War of 1780 to 1784, the company ran into financial difficulties and was liquidated in 1798.

During two centuries of monopolized trade in many areas, the VOC had about 4700 ships under sail, carrying a total of about one million people. The first century accounts for about one third of both figures, the second for two thirds. The trade value of the goods transported to Europe already amounted to 577 million guilders in the first century until 1700 and to 1.6 billion guilders in the second until 1795. The VOC's competitor, the English East India Company (EIC/BEIC), founded in London in 1600 and later the British East India Company, was unable to prevail against the VOC. Only towards the end of the 17th century was there a brief phase during which the EIC/BEIC became a serious competitor.

.jpeg.jpeg)

Share from 1606

Small coin of the Dutch East India Company from 1744

Seal of the Company

The flag of the VOC, here in Amsterdam

The pre-companies

In the early 16th century, Portuguese ships reached Indonesia. They were the first to come via the route around the Cape of Good Hope. Knowledge of this sea route to Asia remained the preserve of Portuguese navigators for several decades. In the last decades of the 16th century, however, Dutch cartography developed into the leading one in Europe. The main contribution was made by Dutchmen such as Jan Huygen van Linschoten, who had been seamen or merchants in Portuguese service. Van Linschoten's Itinerario was not printed until 1596, but his observations and advice influenced commercial decisions shortly after his return from Southeast Asia in 1592. Based on his suggestions, a first official Dutch fleet, led by Cornelis de Houtman, set out for Asia in 1595. The Compagnie van Verre had been founded in Amsterdam especially for this trading voyage, which had received a charter from governor Moritz of Orange. The four ships of the fleet represented an investment of 290,000 florins, of which 100,000 florins alone were to be used to purchase spices in the East Indies. The fleet, which returned to its home port in 1597, had not reached its original destination, the Moluccas, but was so economically successful that five expeditions of various East India companies sailed from different Dutch ports in 1598, and nine more followed in the next three years. The destination of most of the expeditions was Banten on Java, but in 1599 one expedition also reached the Moluccas further east, and parts of one fleet even reached the Banda Islands and Sulawesi. The companies that financed these expeditions were formed solely for the individual voyages, and all profits were realized after the voyage was completed. A foundation of trading stations or a continuous development of trade relations did not take place through these so-called pre-compagnies (Dutch voorcompagnieën).

Very early on, there were voices that spoke out against the fragmentation of Dutch merchants into competing ventures. The "Landadvocaat" of Holland, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, in particular advocated a merger. Merchants from the province of Zeeland, who feared the superiority of the Amsterdam merchants, were the main ones to oppose the merger. Associations of individual companies had already existed since 1598, and as early as 1600 the Eerste Vereinigde Compagnie op Oost-Indie was founded in Amsterdam, which was already equipped with a trading monopoly, but which was still on a city level. This monopoly largely anticipated the later VOC privileges. In 1601, the States of Holland broached the situation before the States-General, who were also in favour of amalgamation. The Zealand companies joined this enterprise after the intervention of Moritz of Orange, so that on 20 March 1602 the federally structured VOC could be founded. With the Generale Vereenichde Geoctroyeerde Compagnie, the States General granted the VOC a trade monopoly (octrooi), initially limited to 21 years, for the trade of goods between the Netherlands on the one hand and the area east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the Strait of Magellan on the other, the so-called octrooigebied, the trade zone. The VOC thus possessed the privilege of being the only private or legal entity in the country to trade with the East Indies. For this privilege the VOC paid 25,000 florins in 1602. By 1647, the company had to pay 1.5 million guilders for this right, and 3 million guilders in 1696 and 1700 respectively. Unlike its British rival, the East India Company, the VOC had decided sovereign rights. These included the right to appoint governors, raise armies and fleets, build fortresses and conclude treaties that were binding under international law. In Asia, therefore, the VOC could act like a sovereign state, even though it formally acted in the name of the United Netherlands. Historians point out that in the age of early modern expansion, during which England, France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain were in strong competition with each other, endowing a well-funded company with such extensive privileges ultimately represented a partial privatization of a country's military expenditures.

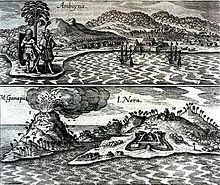

Above: Amboyna, below: Banda Islands. 1655

Organizational features

At each of the original six companies merged into the VOC, a regional administration known as the Chamber was established. The directors of the companies merged into the VOC became the boards of the VOC. However, since eight of these seats were allotted to Amsterdam voorcompagnieën and the other eight to all other companies, the Zealanders continued to fear Amsterdam's domination. The Zealanders' demand that each regional chamber be given equal voting rights now failed because of Amsterdam's opposition, so that a compromise was finally reached to create a seventeenth seat to be filled in turn by a non-Amsterdamer. Of the 17 delegates, in Dutch Heeren XVII, English: the Lords Seventeen, who were at the same time bewindhebbers - active business partners, there were

- eight from Amsterdam

- four from Seeland/Middelburg

- one from Delft

- one from Enkhuizen

- one from Hoorn

- one from Rotterdam and

- one alternately from Zeeland, Delft, Rotterdam, Hoorn or Enkhuizen.

The board of directors thus composed, the Heeren XVII, was to meet in Amsterdam, but for this too a compromise had to be found with the Zealanders. It was agreed on an eight-year cycle. Of these, six years the seat of the board was in Amsterdam under the presidency of an Amsterdamer and then two years in Middelburg under the presidency of a Zealander. The headquarters of the VOC was located in what later became known as the Oost-Indisch-Huis on the Kloveniersburgwal in Amsterdam, and another in Middelburg. The six founding societies continued as regional chambers. The board of the VOC thus corresponded to a federal structure similar to that which had also developed politically between Holland, Zeeland and the cities. An agenda sent out before the meetings by the presiding chamber allowed all chambers to instruct their deputies in detail. For unforeseen points of negotiation, if necessary, the meeting was interrupted for consultations of the deputies with the home chambers.

Shields of arms of the Staten-Generaal van de Nederlanden and cities of Hoorn, Delft, Amsterdam, Middelburg, Rotterdam and Enkhuizen above the entrance to the Castle of Good Hope.

VOC main building in Amsterdam

Questions and Answers

Q: When was the Dutch East India Company established?

A: The Dutch East India Company was established in 1602.

Q: How did the Netherlands give the VOC a monopoly?

A: The Netherlands gave a group of small trading companies a 21-year monopoly to trade in Asia.

Q: What was the VOC's significance in business history?

A: The VOC was the first multinational corporation in the world and the first company to issue stock.

Q: What powers did the VOC have?

A: The VOC had the power to start wars, make treaties, make its own money, and start new colonies.

Q: For how long was the VOC an important company?

A: The VOC was an important company for almost 200 years.

Q: What happened to the VOC in 1800?

A: The VOC became bankrupt in 1800.

Q: What did the VOC's colonies become?

A: The VOC's colonies became the Dutch East Indies, which later became Indonesia.

Search within the encyclopedia