Duisburg

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Duisburg (disambiguation).

Duisburg (with dilation i, /dyːsbʊʁk/, regionally variable [ˈdyːsbʊɐ̯ç] to [ˈdʏːsbʊʀə̆ɕ]) is an independent large city located at the mouth of the Ruhr into the Rhine. The city is part of the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan region with a total of about ten million inhabitants and belongs to both the Lower Rhine region and the Ruhr region. It is located in the Düsseldorf administrative district and, with a population of around half a million, is the fifth largest city in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia after Cologne, Düsseldorf, Dortmund and Essen. According to the city, the population has fluctuated between 498,000 and 503,000 in recent years. The regional center ranks 15th on the list of major cities in Germany. Duisburg was European Capital of Culture in 2010 as part of the Ruhr conurbation.

Located at the starting point of the historic Hellweg and first mentioned in a document in 883, the city developed into an urban trading center as early as the Middle Ages, but lost considerable economic and political importance in the 13th century due to the relocation of the Rhine, which closed the city off from the river. In the 19th century, thanks to its favorable river location with its ports and proximity to the coal deposits in the Ruhr region, Duisburg grew into a major industrial center based on the iron and steel producing industries. In terms of urban development, Duisburg is strongly characterized by industrial facilities of this period, some of which are still in use today and some of which are integrated into parks or, as in the inner harbor, are used by businesses and cultural institutions. The first and third themed routes of the popular Route of Industrial Culture with numerous monuments lead through the Duisburg urban area, namely "Duisburg: City and Port" and "Duisburg: Industrial Culture on the Rhine".

The port (operated by Duisburger Hafen AG) with its center in the Ruhrort district is considered the largest inland port in the world. It shapes the city's economy just as much as the iron and steel industry. Almost a third of the pig iron produced in Germany comes from the eight blast furnaces in Duisburg. Traditional steel production and metal processing in Duisburg is increasingly focusing on the production of high-tech products. As a result of this structural change (steel crisis), which has been ongoing since the 1970s, the city suffers from high unemployment.

With the founding of the Duisburg Comprehensive University in 1972 - which was first merged into the Gerhard Mercator University Duisburg and then into the University of Duisburg-Essen - Duisburg has gained profile as a science and high-tech location. In 2005, the Mercator School of Management with a business focus was established on the campus. Since 2006, the university has also had the NRW School of Governance on the Duisburg campus, the first public governance school in Germany. Other university locations in Duisburg are the University of Applied Sciences for Public Administration, the Folkwang University of the Arts and the FOM - University of Applied Sciences for Economics and Management.

At the same time, as one of the hubs of Central Europe, local logistics is an important economic pillar of the city. Some 60 trains a week run between Duisburg and China on the Trans-Eurasia Express. Duisburg is an important hub of the "new Chinese Silk Road", conveniently located at the intersection of the Ruhr region and the Rhine railroad and at the core of the central European economic area.

Old industrial crane crocodile in landscape park Duisburg-Nord

The Angerpark sculpture Magic Mountain, a landmark of Duisburg

360° panoramic aerial view of Duisburg, drone position: 100 m height above Hansastraße Show as spherical panorama

Swan Gate Bridge in Duisburg's Inner Harbor

Geography

Geographical position

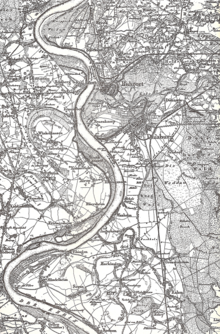

Duisburg is located on the edge of the Niederberg hills at the mouth of the Ruhr into the Rhine. The urban area stretches on both sides of these rivers, with most of it and the city center on the right bank of the Rhine; only the borough of Rheinhausen and the larger part of the borough of Homberg-Ruhrort-Baerl lie on the left bank of the Rhine. In the north of the city, the Alte Emscher and the Kleine Emscher flow into the Rhine.

In state planning, Duisburg is classified as a regional center. As a Rhenish city, it belongs to the Landschaftsverband Rheinland (LVR), and as a city in the Ruhr region, it is a member of the Regionalverband Ruhr (RVR). Duisburg is also part of the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan region and the Rhineland metropolitan region. Since Düsseldorf is only part of the Lower Rhine region in an expanded definition, Duisburg represents the largest city on the Lower Rhine.

The highest elevation in the city is the Haus Hartenfels site at 82.52 m above sea level, while the lowest point is 14.85 m above sea level in Duisburg-Walsum (Kurfürstenstrasse). The average elevation of the city center is 33.5 m above sea level (Duisburg-Mitte, Königstraße/corner of Hohe Straße).

One third of Duisburg's population lives below the water level of the Rhine in a polder area - protected by high Rhine dikes and groundwater pumping stations. The level zero (bottom of the river bed) is 16.09 m above sea level in Ruhrort.

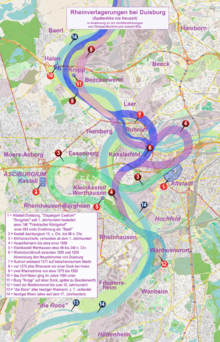

Location on the Rhine

Throughout its history, the Duisburg area has been constantly confronted with Rhine displacements, floods and bank failures:

- Around the turn of time, a loop of the Old Rhine - coming from the Roman Asciburgium (near Moers-Asberg and Duisburg-Rheinhausen) - flowed through the area where the core of the historic city of Duisburg developed at today's Inner Harbor.

- In the year 1000, the main branch of the stream began to turn away from the old Duisburg, even though a tributary continued to provide access to the main branch for over 300 years.

The districts on the right and left bank of the Rhine, which became part of Duisburg through later incorporations, were also affected by Rhine relocations:

- Parts of what is now Wanheimerort were initially located on an island (an oorth) off Wanheim before it was landed on the eastern shore in the 18th century.

- Until the 14th century Ruhrort lay west of the main arm on a Werth or an Oorth in front of Homberg, where it belonged to the parish of Halen on the left bank of the Rhine; it was only through further relocations of the Rhine that Ruhrort lost its insularity and came to the right bank of the Rhine, where it was finally granted its own parish.

- The church village of Halen near Baerl and Knipp Castle, which was situated on a sandbank in front of it, sank into the Rhine around 1595.

- Parts of today's Beeckerwerth were initially located on a large sandbank (on a donk), which was also the site of the first Knipp Castle, destroyed by floods in 1595 (later rebuilt on safe ground in Beeckerwerth).

The authors Tilmann Bechert (excavations Asciburgium) and Joseph Milz (history of the city of Duisburg) as well as the brochure of the City Museum of Duisburg on the occasion of the exhibition on Asciburgium, which runs until March 2014, point out the new findings on the Rhine relocations near Duisburg. The shift of the main branch away from Duisburg, long assumed for the 13th century, has therefore already begun shortly after anno 1000.

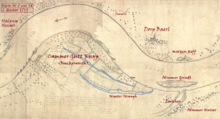

From the Rhine maps drawn in 1713 by the cartographer Johann Bucker it is evident how the course and the riparian region of the Rhine have changed both in comparison with the Middle Ages and in the last 300 years of modern times.

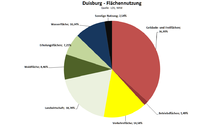

Types of use of the Duisburg urban area

As of December 31, 2009, the cadastral area of the City totaled 23,281.35 hectares. Of this, 8,544.06 hectares (36.7%) were building and open space areas and 347.46 hectares (1.49%) were operational areas. 3,394.24 hectares (14.58%) of the city's territory was used for transportation.

44.69 % of the area consisted of forest, water areas, agricultural areas, parks and green spaces. Duisburg is thus one of the cities with an above-average proportion of green space.

The population density does not exceed 15,000 inhabitants per square kilometer. For example, the population density in Neudorf is around 10,000 inhabitants per square kilometer and in Hochfeld around 15,000 inhabitants per square kilometer. Due to the layout of the districts, the population density does not exceed 6,000 inhabitants per square kilometer.

Neighboring communities

The city of Duisburg is bordered to the west and north by the cities of Moers, Rheinberg and Dinslaken in the district of Wesel, to the east by the independent cities of Oberhausen and Mülheim an der Ruhr, to the south by the city of Ratingen in the district of Mettmann, the independent state capital of Düsseldorf, the city of Meerbusch in the Rhine district of Neuss and the independent city of Krefeld.

Duisburg joined forces with downstream districts to form the Euregio Rhine-Waal special-purpose association back in 1973. This includes the Lower Rhine districts of Kleve and Wesel, cities of Düsseldorf, Arnhem and Nijmegen, as well as some Dutch municipalities near the border.

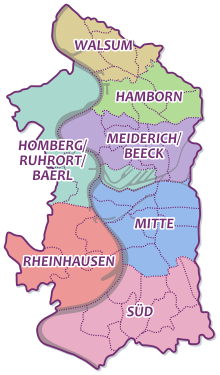

City breakdown

→ Main article: List of districts and boroughs of Duisburg

Since the municipal reorganization of January 1, 1975, the Duisburg urban area has been divided into 46 districts, which are distributed among the seven boroughs of Walsum, Hamborn, Meiderich/Beeck, Homberg/Ruhrort/Baerl, Duisburg-Mitte, Rheinhausen and Duisburg-Süd. In the municipal elections, citizens elect a district council for each city district, which has 19 members. In addition, each city district has a district office.

The Mitte district is the only district with a six-digit population (105,961), making it the largest of the seven urban districts. It is followed by Rheinhausen (77,933), Meiderich/Beeck (73,881), Süd (73,321) and Hamborn (71,891). With 51,528 inhabitants, the northernmost district of Duisburg, Walsum, is the second smallest; the smallest is Homberg/Ruhrort/Baerl, where 41,153 people live. (as of 2008)

With an area of 37.1 square kilometers, the urban district of Homberg/Ruhrort/Baerl is the third largest district in Duisburg in terms of area; only Süd (49.84 km²) and Rheinhausen (38.68 km²) are larger. The other boroughs have areas between 34.98 km² and 20.84 km².

Climate

Due to its location in the west of the Federal Republic, Duisburg has a moderate climate all year round. The total precipitation is therefore about 710 mm. This corresponds approximately to the national average. In addition, Duisburg has a high average temperature; the German Weather Service lists Duisburg together with Heidelberg as the warmest place in Germany. Evidence of this is the officially valid measurement period, which lasted from 1961 to 1990, during which the average temperature in Duisburg was 10.9°C. The high temperature is favored on the one hand by the city climate and on the other hand by the mild winter climate of the Lower Rhine. This is influenced by the proximity to the North Sea and the Atlantic low pressure areas.

| Duisburg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Climate diagram | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monthly average temperatures and precipitation for Duisburg

Source: DWD, data: 2015-2020 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Districts in Duisburg

Location of the city and neighboring districts

Important Rhine relocations from late antiquity to modern times

Bucker's Map No. 1 - Rhine near Duisburg from Wanheim to Homberg 1713

Buckersche map No. 2 - Rhine near Duisburg from Beeckerwerth to Baerl 1713

Land use of the city of Duisburg

History

→ Main article: History of the city of Duisburg

City name

The earliest written mention of Duisburg dates back to 883, when Regino von Prüm, abbot of the Prüm monastery, mentions the name in connection with a Norman raid on the city.

Another medieval mention of the town's name occurred in 1065: "Tusburch in pago Ruriggowe".

The first syllable of the city's name is said to go back to the Germanic "dheus", which means "bulging" or "shining". Duisburggau (Diuspurgau) was the name of the medieval Gau on the Lower Rhine.

Duisburg is not the only place in Europe with this name. A district of Tervuren in Belgium bears the same name. In the Dutch province of Gelderland there is a town called Doesburg, the etymology leading to Mnl. dôse (marsh) or dust (undergrowth) + -burg. A district of Bonn is called Duisdorf. In the Lower Saxon municipality of Bawinkel in Emsland is the village Duisenburg. Likewise a mountain near Bad Driburg, south of Donhausen, carries the name Düsenberg. Other geographical objects also bear a 'Duis' in their name, such as the hill Duisbergkopf in the headwaters of the Wurm near Aachen and the Düesberg in Münster.

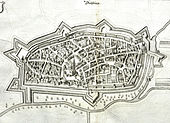

It is also possible that Duisburg is the Roman Dispargum on the right bank of the Rhine mentioned in the "Ten Books of Frankish History" by Bishop Gregory of Tours, from where the Franks led their conquest campaigns into Roman territory on the left bank of the Rhine. In the written explanations to the Corputius Plan of 1566, the identity of Dispargum with Duisburg is still taken for granted.

Roman and post-Roman period

Intensive excavations have proven a permanent settlement of the flood-protected "Burgplatz" already in the first century AD. The Romans maintained a regular presence here to secure the Rhine crossing and the mouth of the Ruhr, which served as a bridgehead for the legions. The Roman settlement Asciburgium mentioned by Tacitus in his Germania (3rd chapter), which is associated with excavations near Asberg south of Moers, could, according to some historians, also have been a transhipment point located directly on the Westphalian Hellweg, used since the Stone Age, and thus one of the ancient amber roads; in this case, the trade route leading from Massilia (Marseille) via the Rhone and Rhine to the North Sea coast.

The "Old Market" was since the 5th century the central trading place of the border town to the Saxon Empire in the ancestral realm of the Franks, which was distinguished by its location on the Hellweg and on a Rhine ford. The first written mention of Duisburg is dated 883, source is the chronicle of Regino of Prüm: the Normans or Vikings conquer Duisburg and spend the winter here. Due to Duisburg's favorable geographical location on a high terrace at the confluence of the Rhine and Ruhr rivers, the city had a strategically important position. Already around 740, the construction of a royal court was begun.

It is disputed whether Chlodio, the first rex or king of the Salian Franks who can be identified by name and who lived in the second quarter of the 5th century, had his headquarters in Duisburg, Germany, or in Duisburg, Belgium, east of Brussels.

Middle Ages and early modern times

At the end of the 9th century Duisburg was affected by the raids of the Vikings in the Rhineland. In the summer of 882, the city was conquered and subsequently occupied by an army led by one Godefried (Duke of Friesland). Two years later, the Viking fortress was successfully recaptured by East Frankish troops under Count Heinrich von Babenberg. In 885, the Viking army returned, but was ambushed by Babenberg's troops on the banks of the Rhine and completely routed.

In the 10th century, the royal court was expanded into a royal palace. At least 18 royal stays in that century are documented. In 929 an imperial synod was held in the town.

Around the 10th century, people in Duisburg began minting pennies on Cologne strike. From Conrad II. (1024-1039), Heinrich III. (1039-1056) and Heinrich IV (1056-1105), Duisburg pennies with independent coin designs are available. The well-cut profile image of the emperor and the arrangement of the city name "DI - VS - BV - RG" in cross or circle form are considered typical. Some of the pennies seem to show the image of a secular complex of the Palatinate on the reverse.

The contract of May 29, 1173 between Emperor Barbarossa and Count Philip of Flanders testifies that heavy pennies of the Cologne foot were minted in Duisburg as late as the 12th century. Then, in 1190, it was agreed between Henry VI and the Archbishop of Cologne, Philip I of Heinsberg, that only two mints would be maintained in the diocese of Cologne, one in Duisburg and one in Dortmund. In the 12th century, the Duisburg mint series breaks off.

In 1002 the Archbishop of Cologne met Henry II and crowned him king together with the Bishop of Liège. In 1173, Barbarossa granted the holding of two fortnightly cloth fairs annually.

Until 1290 Duisburg was a free city, then it was pledged by King Rudolf of Habsburg as a dowry to Count Dietrich of Cleves for 2000 marks of silver. This pledge was changed in 1314 by the German King Louis the Bavarian for 1000 marks from the Count of Cleves to Count Adolf VI of Berg. However, Duisburg already belonged to the County of Cleves again before 1392.

The upward trend of economic development was interrupted by the shifting of the Rhine away from the city around the year 1000 and the increasing silting up of the dead arm of the Rhine in the 13th and 14th centuries. From a prosperous medieval city on the Rhine, which enjoyed support from German kings and Holy Roman Emperors, was a member of the Rhenish League of Cities, and as a merchant city had trade relations with London, Antwerp, Brussels, and other important trading centers, Duisburg developed into a nondescript agrarian town after the millennium flood of 1342, also known as the Magdalen flood. Duisburg's fairs passed to Frankfurt am Main in the 14th century.

In 1407, Duisburg became a member of the Hanseatic League at the suggestion of Cologne.

During the witch hunts from 1513 to 1561 in Duisburg, 13 people were affected by witch trials.

In 1610, the Duisburg General Synod was prepared in Düren. This church meeting, also known as the First Reformed General Synod, took place on September 7 of the same year in the Salvator Church in Duisburg. The synod is considered the birth of the Evangelical Church in the Rhineland.

The work of Gerhard Mercator and the founding of the university in 1655 created the recognition as "Gelehrtes Duisburg" ("Duisburgum Doctum").

In 1666, Duisburg fell with the Duchy of Cleves to Brandenburg-Prussia. In 1674, Frederick William forbade the city to continue calling itself an imperial city.

The period of industrialization

The flourishing of tobacco and textile manufactories in the late 17th century initiated a development that finally led to the "Montanstadt" (mining city) with the high industrialization at the end of the 19th century and the development of the Rhine-Ruhr estuary into the largest inland port in the world.

As late as 1829, Adolph W. Diesterweg wrote succinctly about Duisburg in his "Description of the Prussian Rhine Provinces": "4,500 inhabitants, not far from the Ruhr and connected to the Rhine by a canal, engages in very significant trade, has a high school."

In 1823, the Duisburg district was formed, which included the present-day cities of Mülheim an der Ruhr, Oberhausen and Essen. The eastern areas of the district were separated in 1857 and the new district of Essen was formed.

In 1824, the first large factory was built with the construction of the Curtius sulfuric acid factory. In 1846, Duisburg was connected to the line of the Cologne-Minden Railroad Company. The Duisburg district was dissolved in 1873. Duisburg became a city district and the district of Mülheim an der Ruhr was formed from the rest of the district. From its western part, in turn, the district of Ruhrort was formed in 1887, which included large parts of the present city of Duisburg.

Large industrial plants of the iron and steel industry (including Thyssen and Krupp) settled north and south of Duisburg and, after the incorporation of these areas, played a major role in the development of the city as a whole.

At that time, the principle of "ore comes to coal" prevailed in the production of iron and steel. Coal is the basis for the production of coke, which plays an important role in iron and steel production, and at that time much more coke was needed than ore. Without long transport routes, coal and coke reached the industrial plants in Duisburg, which benefited from the favorable location conditions in the immediate vicinity of the mines, especially in the central and eastern Ruhr region, and from the transport links to the Rhine and Ruhr as well as to the rail network.

The factories that sprang up near old settlement areas attracted workers from the Lower Rhine, the German Empire, the Netherlands, Austria and Poland. New settlements sprang up around the old cores and the population grew rapidly. In 1904 Duisburg became a major city, and in 1905, with the incorporation of Ruhrort and Meiderich, Ruhrort Harbor, whose first basin had been built in 1716, was placed under one administration with the Duisburg Ports.

Weimar Republic and National Socialism

After the end of the First World War in 1918, anarchy also reigned in Duisburg. There were strikes, street battles and firefights between right-wing and left-wing groups. Hyperinflation devalued property values of the middle class. In 1921, French and Belgian troops occupied the city. To mark the French national holiday, French troops paraded through the streets of the occupied city on July 14, 1922. In August 1925, the French and Belgian troops left the city again after the German government accepted the Dawes Plan. However, after a period of economic calm, the city entered a new recession already at the end of 1929. The Great Depression at the beginning of the 1930s hit the city particularly hard. At that time, it had the highest unemployment rate in the German Empire at 34.1 percent.

In 1929, Duisburg and Hamborn were merged to form the city of Duisburg-Hamborn. As early as 1935, this joint urban district was renamed Duisburg.

During the Night of Broken Glass on November 9, 1938, the Nazis in Duisburg destroyed the large synagogue on Junkernstraße as well as synagogues in Ruhrort and Duisburg-Hamborn.

World War II

As an important location for the chemical, steel and metallurgical industries, Duisburg was a regular target of Allied bombers. Not only ports, railroad tracks and industrial plants were targeted, but also the civilian population under the British Area Bombing Directive. Due to its exposed location at the confluence of the Ruhr and Rhine rivers, Duisburg was the entry route to the Ruhr region for British bombers. The city therefore experienced practically daily air alerts from 1942 onward.

According to the official count of the Duisburg air raid police in 1945, the city was subjected to 299 bombing raids. New research has shown that there were a total of 311 attacks on the city. The immense number and severity of the attacks caused considerable destruction to the old cityscape. At the end of the war, about 80 percent of the residential buildings were destroyed or severely damaged. In the post-war years, major areas of the city, including the infrastructure, had to be rebuilt. In the course of this reconstruction, many other historical features disappeared, not only in the old town.

In the period from 1942 to 1944, there was a concentration camp in Duisburg. This was initially located in Duisburg-Ratingsee, but in 1943 it was moved to the already bombed-out Deacon's Institution at Kuhlenwall. Initially, the Duisburg camp was a so-called subcamp of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp; later, the Duisburg camp was subordinated to the Buchenwald concentration camp. The inmates were forcibly deployed, among other things, for cleanup work after air raids.

More detailed information on World War II can be found in the article History of Duisburg.

Postwar and present

After the currency reform, the city was characterized by an unbroken upswing in all areas of life. Coal and steel again became the engines of reconstruction. At the end of the 1950s, the Duisburg labor office district had hardly any unemployed. From 1950 to 1965, North Rhine-Westphalia was consistently the highest contributor to the state fiscal equalization system compared with the other states of West Germany.

The economic power of the Duisburg region was above average and almost 50 percent higher than the national average. There was a huge influx of people into the city. By 1961, the population had soared to 502,933. Despite the coal crisis which began in 1957 and which also led to the closure of coal mines in Duisburg, the steel industry experienced a good boom in the 1960s. The industry increasingly sought foreign labor. However, due to the economic crisis in the first half of the 1970s, the number of employees fell in the 1970s.

In 1975, the towns of Walsum, Homberg, Rheinhausen, Rumeln-Kaldenhausen and Baerl were incorporated. A highly symbolic labor dispute in Rheinhausen to prevent the closure of the Krupp steel mill there gripped the whole of Duisburg and spread to large parts of the Ruhr region. But in the end the massive strike and protest actions, such as the blockade of the Bridge of Solidarity, were unsuccessful, and the Krupp steel mill was finally closed on August 15, 1993.

Duisburg, which 20 years earlier had still been one of the German cities with the highest per capita tax revenues, was now struggling with considerable location problems due to its one-sided, monostructural industry. In 1988, the City of Duisburg and the Lower Rhine Chamber of Industry and Commerce therefore founded the Gesellschaft für Wirtschaftsförderung Duisburg mbH (Duisburg Business Development Corporation) in a joint initiative in a model which was unique in Germany at that time. It was supported and financed by various companies and the city in so-called public-private partnerships. Among other things, it was to help eliminate the land bottleneck in the city and prepare vacated industrial sites for new industries and for the settlement of service and transport companies. However, the new business settlements were not able to compensate for the loss of jobs even in the new millennium.

The considerable loss of purchasing power, which was a consequence of high unemployment and rapid population decline, became particularly threatening for the city. Added to this was the increasing attractiveness of neighboring Lower Rhine towns for shopping. The residents of the Lower Rhine who used to drive to Duisburg for shopping increasingly stayed away as a result of urban developments on the Lower Rhine. The neighboring city of Oberhausen successfully countered this trend with the construction of the CentrO shopping "mall", which further exacerbated the outflow of purchasing power from Duisburg. In Duisburg, too, the much-discussed location of a "mall" (working title MultiCasa) at the main train station, on the site of the disused freight train station, was planned near the city center for many years. Since the city council decided in a controversial decision in 2005 to designate the building site as a special area against the will of the investor, this project is off the table. The current plan is to locate offices and commerce there - as in the inner harbor.

Since September 2008, the inner-city shopping center, Forum Duisburg, has been open on Königstrasse. Together with the City Palais, also newly built, which houses the new Mercatorhalle and a casino, it forms a new attraction in the city center. A new area called Duisburger Freiheit is planned right next to Duisburg's main train station. On the edge of the city center, the inner harbor is to be established as an example of urban redevelopment. There, as the most striking lighthouse project, an office, residential, gastronomy and hotel area called "The Curve" is planned to link the city center and the inner harbor, with construction scheduled to start in early 2018 at the latest.

On May 25, 2009, the city was awarded the title "Place of Diversity" by the German government. As a participant in RUHR.2010, Duisburg was part of the European Capital of Culture project in 2010.

Love Parade in Duisburg

→ Main article: Disaster at the Loveparade 2010

On July 24, 2010, the city of Duisburg became the focus of world attention when 21 people were killed in a mass panic at the Love Parade. Furthermore, at least 652 people were injured, about 40 of them seriously. The Love Parade was held on the site of the former Duisburg Gbf freight station under the motto "The Art of Love".

In 2016, Duisburg made national headlines when, on June 7, the Duisburg Integration Council passed by a large majority a resolution (printed matter 16-0666) entitled: "A lie is a lie and remains a lie. Against the slander of Turkey". In it, the Integration Council rejected the resolution of the German Bundestag of June 2, 2016 on the Armenian genocide and declared that a genocide against the Armenians "never happened". Named members of parliament of Turkish origin who supported the Bundestag resolution were accused by the Integration Council of "betrayal of our common country of origin." Mayor Sören Link suspended the resolution and ordered an extraordinary meeting of the Integration Council on June 20, 2016. He criticized "the partly martial choice of words, the insulting and threatening of individual elected officials".

Incorporations and name changes

At the beginning of the 19th century, the town of Duisburg in the district of Wesel in the Prussian Duchy of Kleve together with the village of Wanheim-Angerhausen, which was an enclave in the Duchy of Berg and the district of Düsseldorf, formed the mayoralty of Duisburg. Among the towns in Kleve, it was the fourth most important after Kleve, Wesel and Xanten.

The city area included other villages or residential areas and settlements, such as Duissern, Feldmark (today's Dellviertel), Neuenkamp, today's Neudorf and Hochfeld. In 1801, Kasslerfeld, which belonged to Moers, was redistributed to Duisburg.

In 1815, after the collapse of French rule as a result of the Congress of Vienna, the town rejoined Prussia and, in the course of the administrative division of the Prussian state in 1816, was assigned to the newly formed district of Dinslaken in the administrative district of Kleve in the province of Jülich-Kleve-Berg. Already in 1822/23 the first changes occurred: The two Rhine provinces were united, likewise the administrative districts of Kleve and Düsseldorf, and the new administrative district of Duisburg was formed from the administrative districts of Dinslaken and Essen. In 1857, the city of Duisburg was removed from the Duisburg mayoralty by the introduction of the city ordinance. The Duisburg-Land mayoralty then consisted only of the municipality of Wanheim-Angerhausen. In 1873 Duisburg became a district-free municipality and in 1902 Wanheim-Angerhausen, which in the meantime belonged to the district of Ruhrort, was reunited with the city of Duisburg.

After that, other incorporations followed, namely:

- on October 1, 1905: the cities of Meiderich (city rights since 1895) and Ruhrort (city rights since 1857, with the municipality of Beeck incorporated in 1904).

- on August 1, 1929: the town of Hamborn (since 1900 a district town in the district of Ruhrort, later Dinslaken and since 1911 a city district) and the localities of Rahm, Huckingen, Buchholz, Wedau, Bissingheim, Mündelheim, Großenbaum, Serm, Ehingen, Hüttenheim and parts of Bockum and Lintorf (all Amt Angermund, district of Düsseldorf). The newly incorporated town was initially given the name Duisburg-Hamborn, which was changed to "Duisburg" in 1935.

- on January 1, 1975: the cities of Homberg (city rights since 1921), Rheinhausen (formed in 1923 from the municipalities of Friemersheim and Hochemmerich, city rights since 1934) and Walsum (city rights since 1958), the municipality of Rumeln-Kaldenhausen (until 1950 Rumeln) and the Baerl district of the municipality of Rheinkamp (until 1950 Repelen-Baerl).

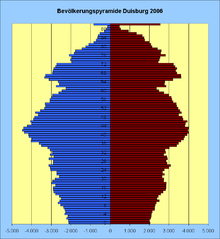

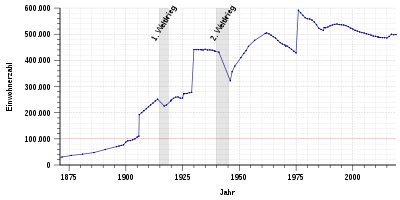

Population development

→ Main article: Population development of Duisburg

In the Middle Ages and early modern times, the city had only about 4000 inhabitants. It was not until the beginning of industrialization that the population in the city increased. In 1903, the population exceeded 100,000 for the first time. Due to incorporations into the city, the mark of 200,000 was already reached in 1906. In 1929, the 400,000 mark was exceeded through further incorporations. Duisburg reached its highest level in 1975 with 591,635 inhabitants, when further districts were incorporated. The population declined continuously until 2014. As of December 31, 2014, Duisburg reported 487,839 residents. Since 2015, the number of inhabitants has been rising.

Demographics

As is the case with almost all large cities, Duisburg in its current boundaries is the result of several territorial reforms. For a long time, the city was the tenth largest in Germany. However, having lost more than 17 percent of its population over the past 30 years, it now ranks 15th. In 2005/2006, the city was overtaken by Leipzig, Dresden and Nuremberg. As recently as the early 1970s, around 650,000 people lived in the area of today's city.

According to the North Rhine-Westphalia State Office for Data Processing and Statistics, 428,594 people lived in the area before the major incorporations on December 31, 1974. To date, the number of inhabitants living there has fallen by 24 percent to just under 325,000. Compared to 1961, this is even a loss of 35 percent. The population density has fallen since 1961 from around 3,500 inhabitants per km² to 2,304 inhabitants per km² in the area before the territorial reform.

In the early 1970s, the proportion of foreigners was less than six percent; today it is about 22 percent. In 2015, about 717 migrants naturalized. From 2004 to 2014, between 1,000 and 1,600 were naturalized annually, and from 2000 to 2003, between about 2,000 and 3,400 were naturalized annually. Overall, according to the 2010 report by the Federal Statistical Office, 32.7 percent of Duisburg's population had a migration background. The largest group came from Turkey (38,063), followed by Poland (3820). Of these approximately 159,000 people, about 84,800 had German citizenship and about 74,700 were foreigners.

At the end of 2018, the share of foreigners was 21.8% (109,471 people), while the share of citizens with a migrant background was 42.4% (213,433 people).

In 2012, there were 159,308 employees subject to social insurance contributions in Duisburg. The number of employees subject to social insurance contributions increased to 174,072 by 2019. Duisburg is one of the cities with one of the highest unemployment rates in western Germany. On November 30, 2014, it was 12.4%. In 2018, it dropped to 10.4% due to the good economy. As purchasing power, the Chamber of Industry and Commerce determines an annual sum of 17,404 euros per inhabitant for Duisburg, which is significantly below the national average of 20,621 euros per inhabitant. Around 76,000 people (approx. 15.1 %) received benefits under SGB II ("Hartz IV") in 2018.

Inner harbor, outer area

Loveparade accident site

Inner harbor, inner area

City fortification

Market on the Duisburg Burgplatz, 1850

Duisburg-Ruhrort Ports, western part, 1931

Duisburg-Ruhrort ports, eastern part, 1931

City wall at the inner harbor

French troops during the occupation of the Ruhr

Population pyramid of Duisburg in 2006

Population development of Duisburg from 1871 to 2018

Duisburg 1647, copperplate engraving Matthäus Merian

Duisburg and Ruhrort in the Topographic Map of Rhineland and Westphalia, about 1850

Overview of the east and center of Duisburg with Sechs-Seen-Platte, bed tower of the sports school in the Sportpark Duisburg, Schauinsland-Reisen-Arena, Salvatorkirche and industry in the north

Medieval three-gabled house, the oldest preserved residential house of Duisburg

Duisburg in the Middle Ages (model photograph)

Search within the encyclopedia