Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus Affair was a judicial scandal that deeply divided French politics and society in the last years of the 19th century. It concerned the conviction of artillery captain Alfred Dreyfus in 1894 by a court martial in Paris for alleged treason in favor of the German Empire, which resulted in years of public controversy and further court proceedings. The conviction of the Jewish officer from Alsace was based on unlawful evidence and dubious handwriting expertises. Initially, only family members and a few people who had doubts about the accused's guilt during the trial campaigned for the retrial and Dreyfus' acquittal.

The miscarriage of justice, which also contained elements of perversion of justice, developed into a scandal that shook the whole of France. The highest circles in the military wanted to prevent the rehabilitation of Dreyfus and the conviction of the actual traitor Major Ferdinand Walsin-Esterházy. Anti-Semitic, clerical and monarchist newspapers and politicians incited sections of the population, while people who tried to come to Dreyfus's aid were in turn threatened, condemned or dismissed from the army. The eminent naturalist writer and journalist Émile Zola, for example, had to flee the country to avoid imprisonment. He had written a famous article in 1898, J'accuse...! (I accuse...!), he denounced the fact that the actual guilty party was acquitted.

The new government formed in June 1899 under Pierre Waldeck-Rousseau relied on a compromise, not a fundamental correction of the wrongful conviction, to end the controversy in the Dreyfus affair. A few weeks after his second conviction, Dreyfus was pardoned. At the same time, an amnesty law guaranteed immunity from prosecution for all legal violations related to the Dreyfus Affair. Only Alfred Dreyfus was exempt from this amnesty, which allowed him to continue to seek a review of the verdict against him. Finally, on July 12, 1906, the Civil Supreme Court of Appeals overturned the verdict against Dreyfus and fully rehabilitated him. Dreyfus was reinstated in the army, promoted to major and, in addition, made a knight of the French Legion of Honour. The punitively transferred Major Marie-Georges Picquart, formerly head of the French foreign intelligence service (Deuxième Bureau) and a key figure in the rehabilitation of Alfred Dreyfus, returned to the army with the rank of brigadier general.

The Dreyfus Affair was the third major scandal in this phase of the Third Republic, after the Panama scandal and parallel to the Fascoda crisis. With intrigues, forgeries, ministerial resignations and overthrows, court trials, riots, assassinations, an attempted coup d'état (23 February 1899) and increasingly open anti-Semitism in sections of society, the affair plunged the country into a serious political and moral crisis. Particularly during the struggle to reopen the trial, French society was deeply divided, even among families.

Jean Baptiste Guth, contemporary account of Alfred Dreyfus during his second trial before the military tribunal in Rennes, Vanity Fair, September 7, 1899.

Further career of the main actors

Auguste Scheurer-Kestner had died in 1899 on the day Dreyfus was pardoned. The French Senate honoured him and Ludovic Trarieux, who had also died in the meantime, in 1906 by deciding to place their busts in the Senate's Gallery of Honour. Émile Zola also did not live to see the complete rehabilitation of Alfred Dreyfus; he died in 1902 in his Paris apartment from carbon monoxide poisoning due to a blockage in his fireplace.

Alfred Dreyfus attended the funeral with his brother, despite Zola's widow's initial concern that his presence would cause riots, and was among those who held vigil at Zola's coffin the night before. Dreyfus, his wife Lucie, and his brother Mathieu were also present when Zola's remains were ceremoniously transferred to the Panthéon on June 4, 1908. During the ceremony, the extreme right-wing journalist Louis-Anthelme Grégori made an assassination attempt on Dreyfus. The two bullets Grégori fired, however, only lightly grazed Dreyfus's arm. He was acting on behalf of Action Française to disrupt the ceremony. In doing so, according to Duclert, he intended to hit both "traitors" Zola and Dreyfus. Ruth Harris describes Grégori's subsequent acquittal by a Paris court as an indication of how strongly the Dreyfus affair continued to shape French society.

Dishonorably discharged from the French army in 1899, Ferdinand Walsin-Esterhazy spent the rest of his life in exile in England. Impoverished for many years, he complained that Jews had destroyed his existence and that the army had betrayed him. The Forchtenstein line of the Esterházy family paid him money, among other things, so that he would take another name. A small inheritance finally secured him a livelihood until he found work as a journalist under various pseudonyms. Esterhazy died in 1923; he claimed shortly before his death that he had written the Bordereau at the behest of Jean Sandherr, then head of the intelligence service. Du Paty, who had been compulsorily retired at half pay after the discovery of the faux henry, was allowed to return to the reserves in 1912 and re-entered active service at the start of the war in 1914. He succumbed to a war wound in 1916. Édouard Drumont, who was one of the most radical anti-Semites with his newspaper La Libre Parole, died impoverished and largely forgotten in 1918. The former war minister Mercier, whose prejudgement of Dreyfus had set the wheels of lies and deception in motion, held a seat in the French Senate until 1920 and maintained that he had acted righteously until his death in 1921.

Many of the Dreyfusards held influential political posts in the years following the rehabilitation of Alfred Dreyfus. Picquart became Minister of War in the cabinet of the Dreyfusard Georges Clemenceau in 1906, the year in which he had been rehabilitated together with Dreyfus, and held this office until 1909. He died in 1914 as the result of a riding accident. Jean Jaurès fought vehemently for workers' rights during Clemenceau's government and was one of the staunchest opponents of increasing militarism and entry into the war against the German Reich. He was assassinated in 1914 just before the war began. For Léon Blum, who was French Prime Minister for a short time several times between 1936 and 1950, the Dreyfus affair was the defining political event of his younger years.

Alfred Dreyfus lived a largely reclusive life after his retirement from the army. In 1901, he published Cinq années de ma vie (Five Years of My Life), an account of his life dedicated to his two children Pierre and Jeanne, covering the period from the day of his arrest until his release from the military prison in Rennes. In it, one can read the bitter disappointment of his firm confidence, even during solitary confinement, that his superiors would do everything possible to clear up his conviction. He also writes about his admiration for all those who had stood up for him.

At the beginning of the First World War, the 55-year-old returned to active service in the army. He first served in the northern military district of Paris, where he had to inspect defensive installations to protect Paris, and later not far from the front in an artillery detachment stationed first near Verdun and then at the Chemin des Dames. By the end of the war, he had been promoted to colonel and officer of the Legion of Honour.

Mathieu Dreyfus' only son Émile and Adolphe Reinach, the son of Joseph Reinach, who had married Mathieu's daughter Marguerite, both fell in the first year of the war. Alfred Dreyfus's son Pierre survived the First World War, in which he had fought as a young officer on the battlefields of the Somme and before Verdun. He was promoted to captain in 1920 and was admitted to the Legion of Honour in 1921.

Alfred Dreyfus died on 12 July 1935; his wife Lucie survived him by more than ten years. During the Second World War, like most members of her family, she fled to the so-called Zone libre and changed her name to escape persecution of the Jews. She spent the last years of the war hiding in a convent of nuns and returned to Paris after the liberation of France, where she died shortly afterwards.

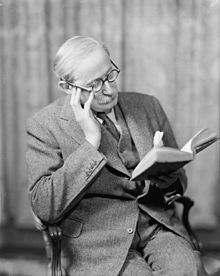

Léon Blum (before 1945)

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the Dreyfus Affair?

A: The Dreyfus Affair was one of the biggest scandals in the history of France. It happened at the end of the 19th century and involved Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army who was accused of being a spy and committing crimes against France.

Q: Who thought that Dreyfus was innocent?

A: People such as his brother Mathieu and a high-ranking officer called Picquart thought that he was innocent. They proved that another soldier, Major Esterhazy, was guilty instead.

Q: How did they prove his innocence?

A: They presented evidence that became so strong that it forced the government to demand a new trial for him. At this new trial, despite their efforts, he was again found guilty by the army.

Q: What happened after he was found guilty?

A: The President of France pardoned him in 1899 and released him from prison due to not wanting an innocent man to suffer any more. Seven years later, he was officially declared innocent and allowed back into the army.

Q: How did people react to this affair?

A: This affair divided France into two sides - those who thought Dreyfus really was a spy and those who thought he was innocent. Many on one side hated Jews and believed that because he was Jewish, he could not be a good Frenchman; this belief is called anti-Semitism while others on the other side believed that an innocent man should not be imprisoned, fearing enemies of France were behind it all.

Q: What island did they send Dreyfus to when they found him guilty?

A: When they found him guilty initially, they sent him to a prison island in South America for life where he stayed until pardoned by President of France in 1899.

Search within the encyclopedia