Dinosaur

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Dinosaur (disambiguation).

The dinosaurs (Dinosauria, from Ancient Greek δεινός deinós, German 'terrible, formidable' and Ancient Greek σαῦρος sauros, German 'lizard') are a group of terrestrial vertebrates that dominated continental ecosystems during the Earth's Middle Ages from the Upper Triassic period about 235 million years ago to the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary about 66 million years ago.

In classical systematics, dinosaurs are considered an extinct branch of reptiles, although they differ significantly in morphology from recent, or present-day, reptiles and are not particularly closely related to most recent reptiles, especially lizards and snakes.

From the cladistic point of view, which is the scientific standard today, both the sauropsids (sometimes alternatively called reptiles altogether) and the dinosaurs include the birds that evolved from small theropod dinosaurs. Thus, not all dinosaurs died out during the mass extinction at the end of the Earth's Middle Ages, but with the birds a special evolutionary lineage of dinosaurs survived to the present day. This lineage proved to be extraordinarily adaptable and successful: birds make up about one third of all recent terrestrial vertebrate species, are represented in all terrestrial ecosystems and, with the penguins, also have a group that is strongly adapted to life in and around water.

However, in zoology, which deals mainly with recent animals, and especially in ornithology, birds are still usually regarded as a class in their own right and not as dinosaurs or reptiles. The same is true in common usage. Even in modern vertebrate paleontology, an informal separation of birds and dinosaurs in the classical sense is common. The latter are also referred to as non-avian dinosaurs, in keeping with the cladistic view.

Paleontologists gain knowledge about dinosaurs by examining fossils, which have survived in the form of fossilized bones, skin and tissue impressions, and trace fossils, which are footprints, eggs, nests, stomach stones or fossilized feces. Dinosaur remains have been found on every continent, including Antarctica, because dinosaurs evolved at a time when the entire mainland was united in the supercontinent Pangaea.

In the first half of the 20th century, dinosaurs were considered to be cold-blooded, sluggish and not very intelligent animals. However, numerous studies since the 1970s have shown that they were active animals with increased metabolic rates and adaptations that enabled social interactions.

Dinosaurs have become a part of global pop culture, starring in some exceptionally successful books and movies like the Jurassic Park series.

Description of the dinosaurs

The English anatomist Richard Owen established the taxon "Dinosauria" in April 1842. According to the current cladistic view, the dinosaurs include all descendants of the most recent common ancestor of Triceratops and the birds. Alternatively, it has been proposed that dinosaurs be defined as all descendants of the most recent common ancestor of Megalosaurus and Iguanodon, since these are two of the three genera Owen named in his initial description of dinosaurs. Both definitions combine the same taxa into the group of dinosaurs: Theropods (bipedal carnivores), Sauropodomorphs (majority large herbivores with long necks and tails), Ankylosaurs (quadrupedal herbivores with massive skin armor), Stegosaurs (quadrupedal bony plate-bearing herbivores), Ceratopsia (quadrupedal herbivores with horns and neck shields), and Ornithopods (bipedal or quadrupedal herbivores).

The known extinct groups of dinosaurs exhibited immense diversity of form. Some were herbivores, others carnivores; some were quadruped, others biped, and still others, such as Iguanodon, could move both bipedally and quadrupedally. Many had armor, horns, bone plates, shields, or dorsal sails. Although known for gigantic size, their size varied considerably; for example, many dinosaurs were only the size of a human or smaller.

However, this diversity of forms was in fact limited exclusively to terrestrial habitats. Only a few species show certain adaptations to a life at and in fresh waters. They also did not actually dominate the airspace (the pterosaurs are a separate group). How well Archaeopteryx, often referred to as the first bird, but still quite dinosaur-like, was able to fly actively (that is, generate dynamic lift) is debatable. Accordingly, it must be assumed that its hitherto unknown, possibly already relatively bird-like immediate ancestors could not fly actively well, if at all. The "four-winged dinosaurs" of the Lower Cretaceous (Microraptor, Changyuraptor), which belong to a different evolutionary lineage than Archaeopteryx, were probably not able to fly actively either, but only to glide from tree to tree.

By 2006, 527 genera of non-bird dinosaurs had been scientifically described out of an estimated total of about 1850 genera. A 1995 study estimates the total number at 3400, many of which have not survived as fossils. On average, two new genera are currently added per month and at least 30 new species per year.

Group-specific characteristics

Compared to their closest relatives within the archosaurs (Lagosuchus, Scleromochlus and the pterosaurs), the representatives of all dinosaur groups are characterized by a number of common derived features (synapomorphies):

- Cranial features: The postfrontal is absent; in the palate, the ectopterygoid overlaps the pterygoid; the head of the quadratum is exposed in lateral view; reduction in size of the posttemporal opening (fenestra posttemporalis, an occipital opening).

- Features of the postcranial skeleton (the skeleton without the skull (cranium)): The glenoid cavity is oriented posteriorly; the hand is asymmetrical with shortened external fingers (IV and V), which are completely absent in higher theropods; the tibia shows a crest-like elevation (cnemial crest) at the anterior superior end; the astragalus (a tarsal bone) shows an upwardly departing process; the middle metatarsal (where toe III attaches) is curved in an S-shape.

While primitive dinosaurs have all of these characteristics, the bone structure of later forms can vary greatly, so that some of the listed characteristics are no longer present or traceable.

In addition, there are several other features that are common to many dinosaurs, but are not called commonly derived features because they are equally found in some non-dinosaurs or do not occur in all early dinosaurs. These include the elongated scapula, three or more sacral vertebrae in the pelvic girdle (three sacral vertebrae have been found in some other archosaurs, but only two in Herrerasaurus), or an open (perforated) acetabulum (closed in Saturnalia).

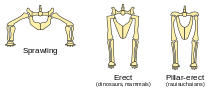

In dinosaurs, the legs stood vertically under the body, similar to most mammals, but unlike most other reptiles whose legs stick out splayed (splayed gait). Their upright posture allowed dinosaurs to breathe more easily while moving, which likely allowed endurance and activity levels that exceeded those of other reptiles with splayed legs. In addition, the straight leg position may have aided in the evolution of gigantism by taking weight off the legs.

Fossil evidence

Paleontologists gain knowledge about dinosaurs by examining fossils; bone finds play a prominent role in this process, providing important data about relationships, anatomy and body structure, biomechanics, and much more.

Further clues, especially about dinosaur behavior, are provided by trace fossils, such as tooth impressions on bones of prey, skin impressions, tail impressions, and especially fossil footprints, by far the most common trace fossils. Trace fossils allow dinosaurs to be studied from a different perspective, as the animal was alive when the tracks were left, whereas bones are always from dead animals. Other information is obtained from fossil eggs and nests, coprolites (fossilized feces), and gastrolites (stomach stones swallowed to break down the food of some dinosaurs).

Reconstructed dinosaur assemblage at "Two Medicine" in Montana (USA)

Pelvic anatomies and gaits of different groups of terrestrial vertebrates

Triceratops skeleton in New York's American Museum of Natural History

Evolution and systematics

Origin

Many scientists long thought that dinosaurs were a polyphyletic group and consisted of unrelated archosaurs - today dinosaurs are considered an independent group.

The first dinosaurs possibly emerged as early as during the Middle Triassic, about 245 million years ago, from original representatives of the avemetatarsalian/ornithodir lineage of archosaurs, as attested by the East African Nyasasaurus, which can be considered either the earliest dinosaur or the closest known relative of the dinosaurs. The fossils of the oldest undoubted dinosaurs Eoraptor and Herrerasaurus come from the approximately 230 million year old (late Triassic) Ischigualasto Formation in Argentina. Eoraptor is considered the most primitive representative and probably looked very similar to the common ancestor of all dinosaurs. Thus, the first dinosaurs may have been small, bipedal carnivores. This view is confirmed by finds of primitive dinosaur-like ornithodires such as Marasuchus and Lagerpeton. These genera, although classified outside the dinosaurs, were probably closely related to the common ancestor of all dinosaurs.

When the first dinosaurs appeared, the niches of terrestrial ecosystems were occupied by various species of primordial archosaurs and therapsids: Aetosaurs, Cynodonts, Dicynodonts, Ornithosuchids, Rauisuchids as well as Rhynchosaurs. Most of these groups became extinct during the Triassic; for example, at the transition between the Carnian and Norian there was a mass extinction in which the dicynodonts and various basal archosauromorphs such as the prolacertiforms and rhynchosaurs disappeared. This was followed by another mass extinction at the transition between the Triassic and Jurassic, in which most other early archosaur groups, such as aetosaurs, ornithosaurs, phytosaurs, and roughosaurs became extinct. These losses left a terrestrial fauna consisting of crocodylomorphs, dinosaurs, mammals, pterosaurs, and turtles.

The early dinosaurs probably occupied the niches vacated by the extinct groups. It used to be assumed that the dinosaurs pushed back the older groups in a long competitive struggle - this is now considered unlikely for several reasons: The number of dinosaurs did not increase gradually, as would have been the case if other groups had been displaced; rather, their number of individuals accounted for only 1-2% of the fauna in the Carnian, whereas after the extinction of some older groups in the Norian, they already accounted for 50-90%. Furthermore, the vertical position of the legs, long considered a key adaptation of dinosaurs, was also pronounced in other contemporary groups that were not as successful (aetosaurs, ornithosuchians, rough-suchians, and some crocodylomorphs).

Systematics and phylogeny

→ Main article: Systematics of the dinosaurs

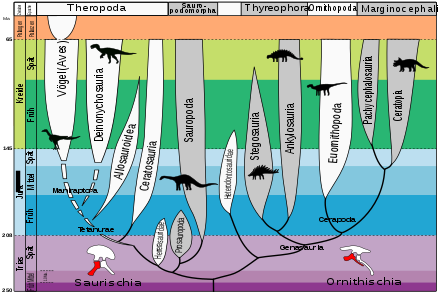

The superorder of dinosaurs, like most modern reptiles, is classified as diapsids. These differ from the synapsids (from which the mammals evolved) and from the anapsids (today's turtles) by two paired skull windows behind the eyes. Within the diapsids, they are counted among the archosaurs ("ruler reptiles"), which are equipped with two more cranial windows. Present-day remnants of this group of reptiles, along with crocodiles, are birds. The dinosaurs themselves are traditionally divided into two orders, Saurischia (also lizard pelvic dinosaurs) and Ornithischia (also bird pelvic dinosaurs). These differ primarily in pelvic structure. Saurischia retained the pelvic structure of their ancestors and can be recognized by pubis and ischium bones protruding from each other. The pubis and ischium bones of the Ornithischia, however, both run parallel to each other obliquely backwards.

The following is a simplified classification of dinosaurs at the family level. A more detailed listing down to the level of genera can be found in the article Systematics of Dinosaurs.

Dinosauria

- Saurischia (lizard pelvic dinosaurs: theropods and sauropods)

- Herrerasauria (early bipedal carnivores)

- Theropoda (bipedal dinosaurs, mostly carnivores)

- Coelophysoidea (Coelophysis and close relatives)

- Ceratosauria (Ceratosaurus and abelisaurids - the latter were important late Cretaceous predators in the southern continents)

- Spinosauroidea (carnivores and possibly piscivores; some had crocodile-like skulls and bony dorsal sails).

- Carnosauria (Allosaurus and close relatives, such as Carcharodontosaurus)

- Coelurosauria (group of various theropods)

- Tyrannosauroidea (small to gigantic, often with reduced arms)

- Ornithomimosauria (ostrich-like, toothless, carnivorous or herbivorous)

- Therizinosauria (bipedal herbivores with long arms and small heads)

- Oviraptorosauria (toothless; their diet and habits are uncertain)

- Alvarezsauridae (small, bipedal and long-legged dinosaurs with short arms)

- Dromaeosauridae (like the classical raptors, for example Velociraptor)

- Troodontidae (similar to dromaeosaurids, but more lightly built, and possibly omnivorous).

- Aves (the birds, the only recent dinosaurs)

- Sauropodomorpha (group of often very long-necked herbivores)

- Prosauropoda (early relatives of sauropods; small to quite large; some may have been omnivorous, biped and quadruped).

- Sauropoda (very large, usually over 15 meters long)

- Diplodocoidea (elongated skulls and tails; teeth are anteriorly directed and pencil-like).

- Macronaria (diverse group of partly giant sauropods)

- Brachiosauridae (very long necks; forelegs are longer than hind legs)

- Titanosauria (diverse; especially common in the Late Cretaceous of the southern continents)

- Ornithischia (avian dinosaurs: diverse group of bipedal or quadrupedal herbivores)

- Heterodontosauridae (smaller herbivores or omnivores with large canine teeth)

- Thyreophora (Armored dinosaurs, mostly quadruped)

- Ankylosauria (armor made of bone plates, some had a bony club at the end of the tail)

- Stegosauria (quadruped, with bone plates and spines)

- Ornithopoda (diverse, were simultaneously quadruped and biped, developed ability to chew, large number of teeth)

- Hadrosauridae (the "duckbills")

- Pachycephalosauria ("thick-headed dinosaurs", with thickened skullcap and head ornaments)

- Ceratopsia (quadrupedal dinosaurs with horns and neck shields, although early forms had only hints of these features).

Evolution, paleobiogeography and paleoecology

The evolution of dinosaurs after the Triassic was influenced by changes in vegetation and the position of the continents. During the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic, all continents were united into the large landmass Pangaea, resulting in a globally uniform dinosaur fauna composed mainly of carnivorous coelophysoids and herbivorous prosauropods. Naked-seeded plants, especially conifers, became widespread during the Late Triassic as a possible food source. Prosauropods could not process plant material in their mouths and relied on other means to break down food in their digestive tracts. The homogeneity of dinosaur faunas continued into the Middle and Late Jurassic: among carnivorous theropods, ceratosaurs, spinosauroids, and carnosaurs dominated, while among herbivores, stegosaurs, ornithischians, and sauropods were common. Important, well known faunas of the Late Jurassic include those of the Morrison Formation in North America and the Tendaguru Beds in Tanzania. Faunas from China, however, already show some differences such as the specialized sinraptorids among carnivores and unusual, long-necked sauropods such as Mamenchisaurus among herbivores. Ankylosaurs and ornithopods became increasingly widespread, but prosauropods became extinct. Conifers and other plant groups such as ferns and horsetails were the dominant plants. Unlike prosauropods and sauropods, ornithischians evolved mechanisms that allowed food to be processed in the mouth. For example, bake-like organs held food in the mouth, and jaw movements allowed food to be ground.

During the Early Cretaceous, the breakup of Pangaea continued, causing the dinosaur faunas of different continents to become more and more distinct. The ankylosaurs, iguanodonts and brachiosaurids spread across Europe, North America and North Africa. Later, especially in Africa, theropods such as the large spinosaurids and carcharodontosaurids were added; in addition, sauropod groups such as the rebbachisaurids and titanosaurs gained importance. In Asia, maniraptors such as the dromaeosaurids, troodontids, and oviraptorosaurs became common; ankylosaurs and early ceratopsians such as Psittacosaurus became important herbivores. Meanwhile, Australia became home to original ankylosaurs, hypsilophodontids, and iguanodontids. Stegosaurs apparently became extinct in the late Lower Cretaceous or early Upper Cretaceous. A major change in the Lower Cretaceous brought the appearance of flowering plants. At the same time, various groups of herbivores evolved tooth batteries that consisted of replacement teeth stacked on top of each other. Ceratopsians used tooth batteries for cutting, while hadrosaurids in particular used them for grinding. Some sauropods also evolved tooth batteries, most distinctly in Nigersaurus.

In the Upper Cretaceous there were three major dinosaur faunas. In North America and Asia, the carnivores were dominated by the tyrannosaurs and various types of smaller maniraptors, while the herbivores were predominantly ornithischians and consisted of hadrosaurids, ceratopsians, ankylosaurs, and pachycephalosaurs. In the southern continents, abelisaurids were the predominant predators and titanosaurs the predominant herbivores. Finally, the fauna of Europe was composed of dromaeosaurids, rhabdodontids (Iguanodontia), nodosaurids (Ankylosauria), and titanosaurs. Flowering plants continued to spread, and the first grasses appeared at the end of the Cretaceous. Hadrosaurids, which ground food, and ceratopsians, which merely cut food, became very common and diverse in North America and Asia towards the end of the Cretaceous. Some theropods, meanwhile, evolved into herbivores or omnivores (omnivores), such as therizinosaurs and ornithomimosaurs.

Feathered dinosaurs and the origin of birds

→ Main articles: Feathered dinosaurs and Evolution of the bird feather.

The first dinosaur considered to be a bird, Archaeopteryx, lived in the Late Jurassic of Central Europe (see Solnhofen Plate Limestone). It probably evolved from early representatives of the Maniraptors, a group of very bird-like theropods from the relatively modern subgroup Coelurosauria. Archaeopteryx exhibits a mosaic of bird and non-bird theropod characteristics, but resembles the latter so closely that at least one fossil without clearly recognizable feather impressions has been incorrectly attributed to Compsognathus, a small non-bird dinosaur. Although the first nearly complete specimen of Archaeopteryx was found as early as 1861, the idea that birds were descended from, or part of, dinosaurs did not gain widespread acceptance until much later, after it was revisited by John Ostrom in 1970. To date, numerous anatomical similarities between theropod dinosaurs and Archaeopteryx have been demonstrated. Similarities are particularly evident in the construction of the cervical spine, the pubis, the wrist, the shoulder girdle, the fork bone and the sternum.

Beginning in the 1990s, a number of feathered coelurosaurid theropods were discovered, providing further evidence of the close relationship between dinosaurs and birds. Most of these finds come from the Jehol Group in northeastern China, a powerful sedimentary sequence famous for excellently preserved fossils. Some of the representatives with down-like feathers (protofeathers) found in the Jehol Group are relatively original coelurosaurs not particularly closely related to birds, for example the compsognathid Sinosauropteryx, the therizinosauroid Beipiaosaurus, and the tyrannosauroids Dilong and Yutyrannus; the latter by far the largest feathered dinosaur, according to current knowledge (as of June 2015), from the Yixian Formation (Barremian to early Aptian) of Liaoning Province. This shows that primitive plumage seems to be an original feature of theropods, or at least coelurosaurs, and that many other theropods, of which only skeletal remains are known today, were also feathered during their lifetime, but their plumage has not been fossilized. This is not affected by the fact that the sediments of the Jehol Group were only deposited in the Lower Cretaceous and are thus geologically younger than the Solnhofener Plattenkalk and Archaeopteryx. Finds of "feathered dinosaurs" are generally rare, which is most likely due to the fact that soft tissues such as skin and feathers only fossilize under particularly favorable conditions, such as those that apparently prevailed in the sediments of the Jehol Group and the Solnhofen Plattenkalk. Many of the feathered non-bird dinosaurs in the Jehol Group would thus be the oldest representatives of their evolutionary lineages that have survived with feathers, although all geologically older representatives of these lineages as well as their common ancestor also had feathers.

However, the contour feathers so typical of birds are only found in representatives of the coelurosaur subgroup Maniraptora, which includes the oviraptorosaurs, the troodontids, the dromaeosaurids and the birds. Protofeathers probably originally evolved for thermal insulation, while contour feathers evolved specifically for visual communication with conspecifics. They took on the function of generating lift when flying or sailing through the air later in evolution. In Microraptor gui, a dinosaur from the Jehol Group that is about the size of a chicken, not only the arms and hands but also the legs are wings equipped with contour feathers, and Microraptor is thought to have sailed from tree to tree on these four wings. However, Microraptor, although geologically younger than Archaeopteryx, is not considered a bird. Instead, its bird-like appearance is due to a parallel evolution (convergence) within the Maniraptora. However, with Jeholornis there was also an early "true" bird in the Jehol group. That Microraptor is not considered a bird is not because it was only capable of locomotion by gliding flight, but because of its skeletal anatomy, which identifies it as a dromaeosaurid. Finally, Archaeopteryx's flying abilities are also quite controversial. One hypothesis for the evolution of the flying ability of "real" birds is that it evolved from gliding flight. The ancestors of Archaeopteryx, possibly even Archaeopteryx itself, would therefore also have been gliders.

Simplified systematics of the dinosaurs

The early dinosaurs Herrerasaurus (large), Eoraptor (small) and a Plateosaurus skull

Questions and Answers

Q: What are dinosaurs?

A: Dinosaurs are a varied group of Archosaur reptiles that were the most powerful land animals of the Mesozoic era.

Q: When did dinosaurs first appear?

A: Dinosaurs first appeared in the Upper Triassic, about 230 million years ago. The earliest date of a dinosaur fossil is 237 to 228 million years ago.

Q: How long did dinosaurs exist for?

A: Dinosaurs existed until the K/T extinction event 66 million years ago.

Q: Are birds related to dinosaurs?

A: Yes, from the fossil record it is known that birds are living feathered dinosaurs and evolved from the earliest theropods during the Jurassic period. They were the only line of dinosaurs to survive to present day.

Q: What adaptations helped make them successful?

A: The first known dinosaurs were small predators that walked on two legs which transformed their whole life-style. Most smaller dinosaurs had feathers and were probably warm-blooded which would make them active with a higher metabolism than modern reptiles and social interaction such as living in herds and co-operation seems certain for some types.

Q: When was dinosaur fossils first recognised as such?

A: Dinosaur fossils were first recognised as such in early 19th century by William Buckland, Gideon Mantell and Richard Owen who saw these bones belonged to a special group of animals.

Q: How have they become part of popular culture today?

A: Today, Dinosaurs have become major attractions at museums around the world and have been featured in many best-selling books and movies with new discoveries reported in media regularly.

Search within the encyclopedia