Deer

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For the German Lutheran theologian and educator, see Georg Karl Hirsche.

The deer (Cervidae) or antlered deer are a family of mammals from the order of artiodactyls (Artiodactyla). The family includes more than 80 species, of which the red deer, the fallow deer, the roe deer, the reindeer and the elk are also common in Europe. In addition, deer are found in Asia, North and South America and with one representative in Africa. The most distinctive feature of the deer are the antlers, which vary in shape and are usually only worn by the males, which are shed annually and formed anew. The main food of the animals consists of plants, whereby soft and hard plant parts are consumed in different measure. Pure grazers, however, as in the hornbearers, do not occur in the deer, which is connected with the formation of the antlers. The social behavior of the animals is very different and ranges from solitary individuals to the formation of large, widely roaming herds. The reproductive phase is marked by characteristic dominance fights.

The systematic division of the deer was and is the subject of numerous debates. Often a division into several subfamilies was proposed. Already in the second half of the 19th century it was recognized that the deer can be divided anatomically into two large groups, one of which is more or less restricted to Eurasia, the other to America. More recently, molecular genetic analyses have supported this dichotomy. The phylogeny of deer dates back to the Lower Miocene, about 20 million years ago. However, some of the earliest forms differed significantly from today's species and most likely did not change their frontal arms in an annual cycle. Today's appearance and behaviour only formed in the further course of the Miocene.

Features

General

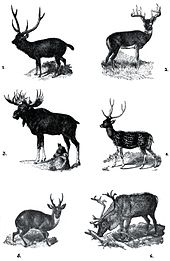

The size of the deer varies considerably: the head-torso length varies between 70 and 310 cm, the shoulder height between 30 and 190 cm and the weight between 5.5 and 770 kg. The smallest living representative is the northern pudu (Pudu mephistophiles), the largest the elk (Alces alces). With most species, with the exception of the muntjak (Muntiacus muntjak), there is a sexual dimorphism in size. In the Tenasserim muntjak (Muntiacus feae) and the water deer (Hydropotes inermis) the females are usually larger than the males, in all other species the male is clearly larger and heavier than the female. The body shape is also variable, within the family two general construction plans can be distinguished. One includes animals with a stocky build, short neck, rounded back as well as strong hind legs and less well developed front legs. These are mostly smaller representatives such as the pudus, the muntjac deer or the spike deer, which still resemble primitive cloven-hoofed animals and possess only short, spike-like antlers. They are often inhabitants of dense forests or of landscapes with luxuriant vegetation, in which they can move quickly by jumping. In addition, the second type is characterized by slender animals with comparatively long limbs and multiple jointed antlers. The members inhabit mainly more open landscapes and are good runners. In both construction plans the tail is rather stubby short. The fur in forest dwellers is predominantly a camouflaged brown or gray coloration; in some species of more open landscapes, such as the Prince Alfred deer (Rusa alfredi) or the Axis deer (Axis axis), a spotted coat has developed; otherwise, accentuation of the head and rump is common. The head is usually elongated, the ears are large and erect. In addition, deer possess three types of glands: In almost all representatives, pre-eye glands are formed, in addition, except for the Muntjak deer, metatarsal brushes occur on the hind legs. Most representatives of the Trughirsche have additionally also interdigital glands.

Antlers

Characteristic for the stags is their antler, a paired formation, which grows out at the frontal bone (Os frontale) from cone-shaped bone formations, called "rosaries". The antlers are connected to these by a bony thickening, the so-called "rose". It consists of bone substance, the largest part of which is hydroxyapatite, a crystallized calcium phosphate, which makes up a good 30% of the antlers. The shape of the antlers depends on the age and the species; in some species they are simple, spear-shaped structures, in others they have widely branched or shovel-shaped forms with numerous tips. The largest antlers of today's stags with a weight of up to 35 kg possess the elk. Comparable to the long bones, a compact layer with a lamellar structure forms the outer mantle of the large and complex antlers of some deer species, while the interior is spongy, but lacks a medullary tube. The spongy nature of the core increases the elasticity of the structure. The rod tips and shoots are composed of compact bone mass alone. The latter is also true of the simple and smaller, sparsely branched antlers of various deer representatives such as the muntjac deer. With the exception of the water deer, all deer species have antlers. However, only in the reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) it is developed in both sexes, otherwise it is an exclusive feature of the males. With these it serves the imponierverhalten and fights around the mating prerogative.

In contrast to the horns of the horn bearers, the antlers are not a permanent formation, but are renewed in the annual cycle. The formation is thereby coupled to the testosterone balance of the male (in the reindeer possibly also to the estradiol, which is produced in both sexes in greater quantity). During the growth phase, the antlers are covered by a short-haired skin called velvet, which is rich in arteries and veins and thus supplies the structure with blood and nutrients. In a departure from normal skin, sweat glands and the like are absent. The growth rate of the antlers is enormous and can be as high as 2.8 cm per day in large deer such as the wapiti (Cervus canadensis) or 417 g in the moose, making the antlers one of the fastest growing organs within mammals. However, the formation of antlers is very costly, as minerals must be partially mobilized from the skeleton, leading to temporary osteoporosis in some species. Once it has reached its full size, the outer layer of skin dries out due to the drying up of the blood supply and becomes itchy, which is why it is stripped or swept off. What remains is a dark and largely dead bone structure, which is connected to the living "rosebush" and is carried for several months.

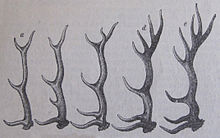

The antlers are shed each year after the mating season and are subsequently regenerated. The shedding of antlers is associated with a drop in testosterone levels, which briefly activates osteoclasts that dissolve the bone at the end of the "rosebush" (the "rose"). The subsequent healing of the wound is probably the trigger for the next antler growth. In most deer, there is an interval of one to two months between shedding and new formation; in true deer, this may be immediately consecutive. In species with a fixed mating season, this shedding occurs at a certain time of year (in the case of roe deer and male reindeer in late autumn, in the case of female reindeer and the other European species in late winter or spring); in species in tropical regions there is no fixed time for this. The formation of antlers already starts in the juvenile stage and begins with the Trughirsche and the Muntjakhirsche in the first year of life, with the real deer from the second year of life. Smaller spits are formed first, and the complex antler structures develop with increasing age. The process of periodic shedding and reformation of antlers was already pronounced in the earliest Lower Miocene deer.

According to phylogenetic analyses, the last common ancestor of today's deer possessed a two-part antler with the (lower) antler bar and the Augspross. Today, this original variant is only preserved in the Muntjak deer. Three-tipped antlers evolved independently within the true deer and the Trughirsche. Thereby it also came to a multiple transformation. Within the true deer, this is how the complex antlers of the red deer (Cervus elaphus) and the wapitis developed, which ideally consist of the eye-shoot, the ice-shoot, the middle-shoot and the crown with three ends, which are connected to each other via the lower and higher pole section. This is found almost identically in the sika deer (Cervus nippon), which, however, lost its ice shoot. The fallow deer (Dama dama) additionally formed a leading shoot as well as a shovel-shaped broadening of the higher pole section. The barasinghas, on the other hand, reduced the ice sprout and the higher pole section, but developed a vertical and a posterior pole section with additional sprouts. In the lyre deer and the David's deer (Elaphurus davidianus), on the other hand, the higher pole section is largely absent, but in addition several cacuminal shoots and a medial shoot occur at the lower pole section, as also in the latter species the augspross enlarged and divided into two ends. The antlers within the Trughirsche took a somewhat different development, whose most original form is still found in the roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). The complex higher pole section is missing, but a forehead sprout was set down. Other forms possess instead of the higher one a secondarily developed upper rod section with additional shoots like the back-shoot and the end-shoots, approximately with the Ren or the representatives of the real Trughirsche. The elk, on the other hand, has no eye and frontal shoots, but oversized terminal shoots. Only the water deer lost the complete antlers.

Skeletal features

The skull generally has a long narrow structure with an elongated rostrum. The nasolacrimal duct (Ductus nasolacrimalis) is forked, at the anterior edge of the orbit are two lacrimal holes (Foramina lacrimalia). The upper incisors are always absent, in the lower jaw there are three per jaw half. The upper canine is enlarged and protrudes tusk-like from the mouth in species with absent or small antlers (water deer, muntjacs), in the remaining species it is reduced in size or absent altogether. The lower canine resembles the incisors and forms a closed row with them. There are three premolars and three molars per half of the jaw, which are rather low-crowned (brachyodont). A crescent-shaped, longitudinal enamel pattern is formed on the chewing surface (selenodont). Altogether, the following dental formula results:

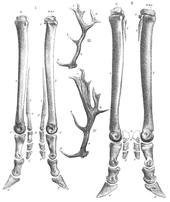

As with all cloven-hoofed animals, the central axis of the foot lies between the rays III and IV, which are enlarged and are the only ones that touch the ground, so the animals stand on toes 3 and 4. The respective corresponding third and fourth metacarpal and metatarsal bones are fused to form the so-called cannon bone. The first toe is completely absent, the second and fifth toes are greatly reduced in size and no longer touch the ground. The degree of reduction of the second and fifth toes on the forefoot is an important criterion for distinguishing the two major lineages of development: Cervinae (true deer and muntjac deer) are "plesiometacarpalia" (from Greek πλησίον (plesion) = "near" and μετακάρπιον (metacarpion) = "metacarpion"), meaning that the proximal (near the middle of the body) parts of the 2nd. and 5th metacarpalia (metacarpal bones) are present, and the respective three phalanges are also formed, but are separated from the metacarpal bones by a large gap. In contrast, the Trughirsche (Capreolinae; Actual Trughirsche, roe deer, and the elk) represent "telemetacarpalia" (from Greek τήλε (tele) = "far" and μετακάρπιον (metakarpion) = "metacarpus"), meaning that only the distal (distant from the middle of the body) portions of the metacarpalia are developed, the associated phalanges articulating directly with the metacarpal bones. The shape and spreadability of the hooves depend on the inhabited landscape and range from more widely spaced hooves in inhabitants of wet to swampy biotopes to broad ones in those in snowy areas.

Anatomical formation of the forelegs in "telemetacarpalia" (left) and "plesiometacarpalia" (right)

.jpg)

Skull of the giant muntjac (Muntiacus vuquangensis)

_skeleton_at_the_Royal_Veterinary_College_anatomy_museum.JPG)

Skeleton of the water deer (Hydropotes inermis)

Development of the antlers of the deer

Different antler types of deer

Different growth stages of antlers

Sika deer (Cervus nippon) as inhabitants of more open landscapes

Crested deer (Elaphodus cephalophus) as inhabitants of more closed landscapes

Distribution and habitat

The natural range of the deer includes large parts of Eurasia and America, they reach their highest diversity in South America and Southeast Asia. In Africa, they occur only in the northwestern part, in the areas south of the Sahara they are absent and are replaced there by the hornbearers. Deer have been introduced by humans to some regions where they were not native, including Australia, New Zealand, New Guinea, and some Caribbean islands. Deer inhabit a wide variety of habitats. The majority of species prefer closed forests, more open woodlands, and forest edges. Some forms, such as the muntjac deer or the spike deer, are generally found in dense vegetation, while others show a more plastic behaviour and mostly occur in forest edges with transition to more open landscapes. Only a few representatives like the reindeer or the pampas deer (Ozotoceros bezoarticus) adapted directly to open landscapes, furthermore the swamp deer (Blastocerus dichotomus) and the water deer, among others, live in swamp or marsh areas. The deer have developed both lowlands and highlands up to 5100 m and inhabit tropical climates as well as the arctic tundra.

.jpg)

roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), the most common deer species in Central Europe

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the family of deer called?

A: Deer are a part of the family Cervidae.

Q: What is a male deer called?

A: A male deer is referred to as a stag or buck.

Q: What is a female deer called?

A: A female deer is known as a hind or doe.

Q: What do you call a young deer?

A: Young deer are referred to as fawns, kids, or calves.

Q: How many species of deer exist?

A: There are approximately 60 species of deer.

Q: Where did they originally live in the world?

A: Deer originally lived in the northern hemisphere, including Europe, Asia, North America and South America.

Q: Have humans introduced them to other places in the world? A: Yes, humans have introduced them to other places such as Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii and South Africa where they did not naturally occur.

Search within the encyclopedia