Alfred Rosenberg

![]()

This article is about the ideologue and politician Alfred Rosenberg. For other persons, see Alfred von Rosenberg.

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg (Russian Альфред Вольдемарович Розенберг, Alfred Woldemarowitsch Rosenberg; b. 31 December 1892jul. / 12 January 1893greg. in Reval; † 16 October 1946 in Nuremberg) was a politician and leading ideologue of the Nazi Party during the Weimar Republic and Nazi era. As a student he witnessed the revolution in Moscow in 1917. Under the influence of Russian emigrants, he interpreted this as the result of a Jewish-Masonic world conspiracy. With this conception he later decisively shaped the ideology of the NSDAP. From 1920 onwards, Rosenberg contributed significantly to the intensification of anti-Semitism in Germany with numerous racial ideological writings. During World War II, he and his Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR) undertook raids throughout Europe, especially to loot cultural property. As head of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories (RMfdbO), he pursued the project of Germanizing the occupied eastern territories while systematically exterminating the Jews as part of his Ostpolitik. Rosenberg was tried at the Nuremberg Trial of the Major War Criminals, found guilty on all four counts, sentenced to death, and executed.

Alfred Rosenberg (1941), Photo: Hoffmann (Federal Archive)

Weimar Republic

Political writer

In the spring of 1919, he gave his first political speech in Munich, in which he formulated his rejection of the revolution in deliberate imitation of a speech by the far-right Duma deputy Markov II. Despite important contacts, the situation for Rosenberg was not easy at first. He was almost penniless, spoke only poor German, and was a Russian citizen until February 1923; and after the suppression of the soviet republic, Rosenberg was only able to remain in Munich through the intercession of his publisher, the German nationalist Thule member Julius Friedrich Lehmann.

With the beginning of the Weimar Republic, Rosenberg published his first writings such as Die Spur des Juden im Wandel der Zeiten (1919), Das Verbrechen der Freimaurerei. Judentum, Jesuitismus, Deutsches Christentum (1921), Börse und Marxismus oder der Herr und der Knecht (1922) and Der staatsfeindliche Zionismus. The summary of which is: "Zionism is [...] a means for ambitious speculators to create for themselves a new staging ground for world overgrowth."

He spread a theory, adopted by the Russian far right, of the "Judeo-Masonic world conspiracy" (židomasonstvo), which aimed to "undermine the existence of other peoples". To this end, the Freemasons had brought about the World War and the Jews the Russian Revolution. Therefore capitalism and communism were only apparent opposites, in reality they were one and the same pincer movement with which "international Jewry" was striving for world domination (Die Hochfinanz als Herrin der Arbeiterbewegung in allen Ländern, 1924). This idea, he argues, goes back decisively to an anti-Semitic writing by Dostoevsky, which Rosenberg repeatedly cited. The emergence of these thoughts, however, must also be seen in the context of the crisis-ridden climate of early 1920s Germany. Here they found numerous adherents and contributed to the image of a "Jewish-Bolshevik world conspiracy" that was to form the core of Hitler's thinking, propaganda, and policies. Rosenberg's biographer Ernst Piper even wrote that it was Rosenberg who played a decisive role in conveying to Hitler the image of the supposedly Jewish character of the Russian Revolution.

In 1923 Rosenberg published a commentary on The Protocols of the Wise Men of Zion, an anti-Semitic inflammatory pamphlet that he had been working to spread since his arrival in Germany and which was quoted several times in Mein Kampf two years later. It states:

"A new epoch is beginning today in the midst of the collapse of an entire world. [...] As one of the portents of this coming struggle for a new world order stands the realization of the nature of the demon of our present decay."

The influence of Russian right-wing extremist thought on Rosenberg was not limited to his time in Russia; he studied the emigrant newspapers of the Russian right-wing extremists carefully and made extensive use of them for his own activities. According to Laqueur, what he had to say about Jews and Jewish culture can be read almost word for word in the writings published by Fyodor Winberg in 1919, and the pamphlet Plague in Russia, published in 1922, can be described as Rosenberg's variant of Fyodor Winberg's Krestnyj Put and also represents the culmination of the appropriation of emigrants' positions.

Rosenberg was a member of the Wirtschaftliche Aufbau-Vereinigung (Economic Reconstruction Association) founded by Scheubner-Richter, which sought to restore the pre-revolutionary order in Europe, and, like other members of this organization, engaged in propaganda for German-Russian cooperation against world Jewry. Accordingly, his image of Russia in the first post-war years was by no means clearly Russophobic, as in his later writings; rather, he made positive references between the peoples and their culturally important artists and writers.

His view further led him to see the distancing of National Socialism from National Bolshevism and other forces seeking rapprochement with the Soviet Union as a major task. Like other Aufbaum members, he interpreted the extermination policy carried out by the Bolsheviks as a deliberate annihilation of the Russian national intelligentsia and warned that Russia's fate threatened other countries as well. Although he condemned the Bolsheviks' actions, he also noted their "expediency".

As early as 1921, he had moved with Dietrich Eckart to the Völkischer Beobachter, whose editor-in-chief he took over from Eckart in February 1923; this shows the strong position Rosenberg had built up within the National Socialist movement with his conspiracy theories. From 1937 he was finally editor of the paper.

Prohibition phase of the NSDAP

Rosenberg took part in the "March on the Feldherrnhalle" in 1923, but unlike other participants in the putsch, he was not charged. While Hitler was serving his prison sentence, he entrusted Rosenberg with the leadership of the now banned NSDAP, a task Rosenberg, however, was hardly up to. Under the pseudonym Rolf Eidhalt (an anagram of Adolf Hitler), he founded the Großdeutsche Volksgemeinschaft (GVG) in January 1924, but he was unable to prevent the fragmentation of the National Socialist movement. He was soon forced out of the leadership of the GVG by Hermann Esser and Julius Streicher.

As director of the anti-Semitic monthly or quarterly Der Weltkampf, which he edited from 1924, Rosenberg worked closely with Gregor Schwartz-Bostunitsch.

After Rosenberg's first marriage had been divorced in 1923, he married a second time in 1925, the marriage with Hedwig Kramer lasted until his death. In 1930, daughter Irene was born, a son died shortly after birth.

Combat League for German Culture

In 1927, Rosenberg was commissioned by Hitler to found a National Socialist cultural association. Although apparently originally intended as a cultural association of the party, the association did not appear in public until 1929 as an ostensibly non-partisan "Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur". Here, various manifestations of Classical Modernism, such as Bauhaus architecture, Expressionism and abstraction in painting, or twelve-tone music, were defamed and fought against across the board as "cultural Bolshevism.

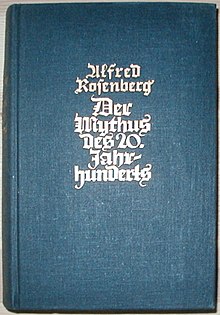

"The Myth of the 20th Century"

→ Main article: The myth of the 20th century

The book The Myth of the 20th Century, published in 1930, was intended as a sequel to Houston Stewart Chamberlain's work The Foundations of the 19th Century. According to Rosenberg, a new "religion of blood" would have to replace a Christianity steeped in "Jewish influences" by replacing it with a new "metaphysics" of "race" and its inherent "collective will".

Rosenberg envisioned "race" as an independent organism with a collective soul, the "racial soul"; he wanted everything individual suppressed. According to Rosenberg, the only race capable of producing cultural achievements was the "Aryan race". In contrast to the Jewish religion, which Rosenberg regarded as devilish, there was something divine in the "Aryans". In Rosenberg's book, Jesus Christ became a transfigured "embodiment of the Nordic racial soul". Thus, in his opinion, Jesus could not have been a Jew. Marriage as well as sexual intercourse between "Aryans" and Jews should also be made punishable by death.

Following the natural philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, Rosenberg saw the "will" as not subordinate to any morality; if a strong leader gave appropriate orders, they could be carried out. He thus paved the way for the National Socialist world view and an action in which other peoples were to be oppressed and a "pure" race bred.

Rosenberg's racial doctrine, which he outlined against the background of his criticism of Christianity and the church, provoked numerous critical reactions. While the Protestant theologian Walter Künneth wrote an extensive refutation on behalf of the church, the Protestant Jena theology professor Walter Grundmann took his cue from Rosenberg's call for a "Germanization" of Christianity and founded the Institute for the Study and Elimination of Jewish Influence on German Church Life.

Clemens August Graf von Galen, the Catholic Bishop of Münster, had the anonymous publication Studien zum Mythus des 20. Jahrhunderts (Studies on the Myth of the 20th Century) published in his diocese at the end of 1934 as an official supplement to the official church gazette of his diocese. In it, among others, the Bonn church historian Wilhelm Neuß turned against Alfred Rosenberg's racial ideology laid down in the Myth of the 20th Century. Von Galen, after the Archbishop of Cologne, Karl Joseph Cardinal Schulte, had withdrawn his consent to the publication of the study as an official publication two days before it went to press, had written a brief foreword to the paper that bears his name. In his pastoral letter at Easter 1935 he dealt with Rosenberg's theses in an aggravated tone. He calls there "idolatry, ... idolatry, ... relapse into the night of paganism", if the nation is seen as origin and final goal.

Member of Parliament

In 1930 he became a member of the NSDAP for Darmstadt in the Reichstag, where he was particularly active in the Foreign Affairs Committee.

"The Myth of the 20th Century," cover of the 143rd-146th edition of 1939.

After the end of the war

Nuremberg Trial

Alfred Rosenberg was taken to Kiel the day after his arrest in Mürwik and from there transported by plane to Luxembourg. There, in Bad Mondorf, he was interned with other major war criminals in the Palace Hotel, where he remained until his transfer to Nuremberg in August 1945. The Nuremberg trial of the major war criminals began for the accused on November 21, 1945. Rosenberg was charged with conspiracy, crimes against peace, planning, initiating and waging a war of aggression, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. He was found guilty and sentenced to death. The verdict was based, with regard to the conspiracy, on Rosenberg's function as a "recognized party philosopher" and, with regard to the crimes against peace, on Rosenberg's activity as head of the Foreign Policy Office. In particular, he was jointly responsible for the attacks on Denmark and Norway. With regard to the crimes against humanity, the court referred to Rosenberg's function in the Reichsleiter task force and in the East Ministry. He was also proven to have been complicit in the procurement of forced laborers.

Rosenberg asked his defense counsel to get him the diaries, which he knew must be at least partially in the hands of the Americans. The International Military Tribunal then claimed that they were "untraceable." Robert Kempner, the chief deputy prosecutor for the United States, did not hand them over. Rosenberg never entered an admission of guilt, but rather, like most of the other co-defendants, attempted to shift the blame to the trio of Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler, and Martin Bormann, who had already died by then, and to remove himself from responsibility. Rosenberg remained committed to his own Nazi racial ideology to the end. Still in prison he wrote:

"National Socialism was a European answer to the question of a century. It was the noblest idea for which a German was able to use the powers given him. It was a genuine social worldview and an ideal of blood-based cultural purity."

On October 1, 1946, Alfred Rosenberg was sentenced to death and, along with nine other convicts, executed by hanging in Nuremberg's justice prison in the early hours of the morning on October 16. The body was cremated one day later in the municipal crematorium at Munich's Ostfriedhof and the ashes scattered in the Wenzbach, a tributary of the Isar.

Diaries

In 2013, US authorities announced that Rosenberg's diaries, amounting to 425 pages, had resurfaced. Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) officials seized them in upstate New York. German-born lawyer Robert Kempner, who was deputy to U.S. chief prosecutor Robert H. Jackson during the Nuremberg trial, had apparently taken possession of them after the trial and retained them upon his return to the United States. They are said to concern the years 1934 to 1944 and were handed over in June 2013 to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, which intends to evaluate the records scientifically. Since late 2013, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has posted handwritten pages and transcripts online, and in 2018 the diaries covering the years between 1934 and 1944 were finally published as an annotated book edition by historians Jürgen Matthäus and Frank Bajohr. Previously, only a partial edition from the years 1934/35 and 1939/40 had been known.

Impact history

Rosenberg's image was subject to strong fluctuations for a long time. Among his contemporaries and during the immediate postwar period, the author of the myth of the 20th century was regarded as a demonic master thinker, a murderously cool intellectual of the NSDAP and its chief ideologue. In an anti-fascist book published in Paris in 1934, the phrase "Hitler orders what Rosenberg wants" was attributed to a Hitler biographer.

This image remained unchallenged until the 1960s. Then Joachim Fest formulated his judgment based on Albert Speer's memoirs. Fest quoted, for example, that Rosenberg had been dismissed by Hitler only as a "narrow-minded Balte who thinks in a terribly complicated way" - so his importance did not seem to have been as great as had hitherto been assumed. In the same year as Fests Gesicht des Dritten Reiches, Ernst Nolte's Der Faschismus in seiner Epoche (Fascism in its Era) was published, in which it was stated that National Socialism was in its essence a reaction to communism, which was perceived as a threat, and therefore not an ideology in its own right.

Younger German historians of the late 1960s (Anglo-Saxon historiography continued to focus on the problem of ideology, but was initially hardly taken up in Germany) aimed in a similar direction. Reinhard Bollmus and Hans-Adolf Jacobsen worked out, on the basis of the offices and departments headed by Rosenberg, that National Socialism had not established a monolithic Führerstaat, but a polycracy without a clear hierarchy, in which individuals, offices and authorities fought each other. Reinhard Bollmus, who in 1970 was still inclined to place Rosenberg's importance in the National Socialist era in the shadow of historical interest, wrote, however:

"Rosenberg, on the contrary, determined all his powers himself, as he believed they arose from the Fuehrer's mandate, and also determined his fields of activity without instructions from higher authority. Hitler and Hess expressed no approval, but neither did they deny the correctness of the action. They gave no advice, set no definite tasks, imposed no prohibitions, and made no comment on the question whether Rosenberg's interpretation of the Weltanschauung was authoritative alone, in part, or even at all."

In the biography of Rosenberg by Ernst Piper (2005), the focus was no longer on the easily graspable but, in the opinion of many historians, less influential myth, as it had been in the 1950s, but on the major role Rosenberg played as a producer of anti-Semitic ideology and propaganda, such as the Völkischer Beobachter and other publication organs. His widespread conspiracy theories, his daily diatribes against everything Jewish, his paranoid but effective equation of Judaism and the Soviet regime justified for Piper the long ostracized term "chief ideologue", which his book carries in its subtitle.

A. Rosenberg after his execution

1946 in the Nuremberg courtroom: Rosenberg (front row, left)

1945/46: Alfred Jodl, Hans Frank and Alfred Rosenberg (from left to right) during the Nuremberg Trial

Search within the encyclopedia