Currency

A currency (mhd. werunge for 'guarantee') is, in the broader sense, the constitution and order of the entire monetary system of a state, which concerns in particular the determination of the coin and note system within the currency area. The currency area is the area of validity of a currency as a means of payment. It enables the transfer of goods and services without providing anything in return in the form of other goods and services.

Currency or monetary unit is also the type of money recognised by the state (the legal tender of a country). In this case, currency is then a sub-form of money. Most currencies are traded on the international foreign exchange markets. The resulting price there is called the exchange rate. Almost all common currencies are now based on the decimal system, i.e. there is a main unit and a sub-unit, with the sub-unit representing a decimal fraction (usually one hundredth) of the value of the main unit (decimal currency). In specialist circles, the sub-unit is also called the sub-currency.

In the respective countries, the finance minister or the state central bank exercise control over the currency or monetary policy. In almost all Western countries, the central banks have a large degree of autonomy, i.e. the government cannot influence the central bank at all or only to a very limited extent or indirectly.

If a currency is tradable and exchangeable worldwide, it is referred to as convertible. If a currency is backed by gold and/or silver and the exchange of banknotes into the respective metal is possible at any time, convertibility is also given in this context.

There are currently over 160 official currencies worldwide, but only the US dollar and, increasingly, the euro are regarded as international reserve currencies. In addition, there are complementary currencies that are only accepted regionally as a medium of exchange alongside the official money.

If a currency has lost a great deal of confidence among the population, substitute currencies such as cigarettes (e.g. cigarette currency in Germany after the Second World War) are often formed, which then serve as a means of payment and exchange. So-called emergency money also serves as a substitute for the official currency in times of crisis. Often currencies of other countries become substitute currencies. A well-known example is the use of the "Westmark" in the GDR alongside the GDR mark. In particular, the so-called "blue tiles" (100 DM notes) were a popular medium of exchange on the black market.

Banknotes from different countries

Young people trading cigarettes on the black market, West Germany 1948

Overview

In a broad sense, the term currency refers to the monetary constitution, i.e. the legal order of the monetary system of a state. More often, however, currency refers to the legal tender of a state. Most countries have their own national currency. An exception is the euro area, with the euro as the common currency for 19 countries (monetary union).

Payment

→ Main article: Means of payment

Currencies are issued by an issuer, nowadays usually by the central bank. It is usually mandated by law to produce and issue the currency. Currency designed as legal tender has a legal obligation to accept within the state, i.e. a creditor is obliged to accept repayment of a monetary debt with the legal tender unless otherwise validly agreed. This ensures its value as a means of payment. In Germany and the other participating Member States of the European Economic and Monetary Union, euro cash has been legal tender since 1 January 2002: in accordance with the second sentence of Section 14(1) of the Bundesbank Act, the euro notes issued by the ECB are the only unlimited legal tender in this respect.

Currency symbols and abbreviations

For many currencies own characters (mainly with double bar) or abbreviations, the currency symbols of a currency unit are used, for example:

- £ for the pound

- $ for a whole range of currencies, including the US dollar

- ¥ for yen

- 元/¥ for Renminbi/Yuan

- € for Euro

- ₦ for Naira

- ₹ for Indian Rupee

for the Russian rouble

for the Russian rouble

There are usually two different abbreviations: On the one hand, a sign or letter abbreviation without a standardised structure (e.g. "Fr.", "SFr." or "sfr" for Swiss francs), which is mainly used domestically; on the other hand, a standardised three-letter abbreviation in accordance with ISO standard 4217 (e.g. "CHF"), which is mainly used in international currency trading.

Exchange rate

→ Main article: Exchange rate

In order to be able to make purchases abroad, it is usually necessary to exchange the domestic means of payment for the foreign means of payment. Even if, for example, a German exporter has sold goods abroad and received money in foreign currency in return, he will usually exchange it for domestic currency. The exchange takes place at the exchange rate valid at the time. The exchange rate is the exchange ratio of two currencies.

The buying and selling of currencies takes place on the foreign exchange market. Transaction costs arise in connection with the exchange of one currency for another. In addition to credit institutions, major market participants in the foreign exchange market include larger industrial companies, private foreign exchange dealers, foreign exchange brokers and trading houses. The central banks of various countries can also intervene in the foreign exchange market through foreign exchange market intervention for economic policy reasons. Due to increasing international integration, international trading of currencies in the foreign exchange market has become much more important in recent decades. Currencies are traded both for speculative purposes and for exchange purposes based on real economic considerations.

Since 1999, the European Central Bank has been determining euro reference rates for selected currencies. In addition, the German banks have introduced the euro fixing, i.e. reference rates for eight important currencies (USD, JPY, GBP, CHF, CAD, SEK, NOK, DKK) are determined daily and serve as the basis for the currency transactions of the banks participating in the euro fixing.

Monetary policy

→ Main article: Monetary policy

Monetary policy is all measures aimed at shaping the internal and external value of money. Monetary policy in the narrower sense (= shaping the external monetary value) is the shaping of monetary relations with foreign countries and the safeguarding of the external economic balance. Monetary policy measures directed at the domestic market are also referred to as monetary policy. Monetary policy in the narrower sense can pursue various objectives:

- Price stability

- Reduction of transaction costs

- Achieving a high level of international competitiveness

- Achieving a high level of domestic purchasing power

- External balance

Which of these sometimes conflicting goals a country is pursuing is also reflected in the choice of exchange rate regime:

With a fixed exchange rate, the central bank is obliged to keep the exchange rate of its own currency stable on the foreign exchange market by buying or selling foreign currency (foreign exchange intervention), depending on the market situation. For example, nowadays some countries have pegged their national currency to the value of the dollar or the euro. The advantage of a fixed exchange rate is the planning security for internationally operating companies. Exchange rates are an important calculation factor for trade and capital transactions with foreign countries. If, for example, an invoice is denominated in a foreign currency and this currency appreciates until payment due to exchange rate fluctuations, then the goods purchased will be more expensive in real terms than initially calculated. The disadvantage of fixed exchange rates is that it becomes difficult or impossible for a central bank to pursue an independent (national) monetary policy.

Nowadays, most currencies have flexible exchange rates. The exchange rate is therefore formed on the foreign exchange market in the interplay of supply and demand. Currency fluctuations lead to uncertainty and reduce the planning and calculation security of internationally operating companies. An appreciation of the domestic currency causes domestic companies to lose competitiveness because foreign goods and services become relatively cheaper, while exports become relatively more expensive.

Currency crisis

A currency crisis is an economic crisis in the form of rapid and unexpected currency devaluation. It is triggered by the unintentional abandonment of a fixed exchange rate to one or more other currencies or to gold. The cause or consequence of currency crises can be financial and economic crises.

Although currency crises vary in nature, some leading indicators can be identified that occur very frequently. These include (persistent) current account deficits, strong foreign exchange inflows in the capital account, an increase in short-term external liabilities, high credit growth and strong asset price increases (especially real estate and equities).

After the outbreak of a currency crisis, typical crisis symptoms can again be observed. These include increasingly shorter maturities in foreign debt, increased settlement of foreign liabilities with foreign currencies, higher interest rates for borrowers in the debtor country, high losses in the value of shares and real estate, reversal of capital flows (capital flight) and heavy losses in currency reserves.

Examples of currency crises after the end of the Bretton Woods system include the dollar crisis of 1971, the Latin American debt crisis of 1982/83, the Mexican crisis of 1994/95 (Tequila crisis), the Southeast Asian financial and currency crisis of 1997 (Asian crisis) and the Brazilian crisis of 1999.

.jpg)

Exchange rates of an Asian exchange office.

Cumulative current account balances 1980 to 2008: green = positive, red = negative, grey = no data.

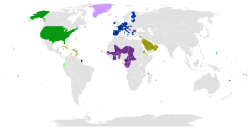

Countries with currencies pegged to the euro or the US dollar: USA Other countries with US dollar as legal tender Currencies with a fixed exchange rate to the US dollar Currencies with a narrow exchange rate band to the US dollar Members of the European Monetary Union with euro Other countries with euro as legal tender Currencies with a fixed exchange rate to the euro Currencies with a narrow exchange rate band to the euro

Historical development

→ Main article: History of money

Earlier forms of currency up to the age of coinage

Ancient Orient, Egypt and Africa

The classical functions of money (medium of exchange, means of payment, measure of value and store of value) were already fulfilled at the beginning of the 3rd century BC by metals such as copper, silver, tin and gold. In addition, grain functioned as a medium of exchange and a measure of value. However, the palace economy in connection with the oikos economy as well as the subsistence production associated with them was an obstacle to the development of a monetary economy, since goods not produced by the people themselves were usually procured by means of barter or service. Coinage therefore only became established later and initially only in some branches of the economy.

In Africa at that time there existed the most diverse forms of currencies. What they all had in common was their function as a store of value. Thus, for example, pearls, ivory, cattle or also the manilla currency functioned as a means of payment. In the 15th century, with the advent of the slave trade, manilla rings, which served as payment for slaves, were particularly important.

Greece

In ancient Greece there was initially a whole class of goods, each of which embodied individual monetary functions.

- Valuer: Cattle

- Value store: Jewels

- Means of exchange: wine, copper, iron and slaves

- Means of payment: arrowheads and roasting spits

In the course of time, precisely weighed uncoined precious metal prevailed as a means of payment in the Greek poleis. It can be assumed that money was of crucial importance for standardized public payments in the polis. The first real coins date to about 600 BC and were minted in western Anatolia. These coins were made of a naturally occurring silver-gold alloy and were most likely used only locally. However, the use of coins quickly became established throughout Greece, whereby (due to better extraction possibilities in mines - in contrast to the gold currency in the Persian Empire) silver was generally used as the metal of coinage (in exceptional cases also gold and bronze). The guaranteed weight was guaranteed by stamps of the polis. The most important currency was the drachma, which was again used as the currency of Greece from 1831 to 2001 (Greek drachma).

However, it is not until the beginning of the 5th century BC that one can speak of a monetary economy in the true sense. The center of ancient monetarization was Athens, whose currency circulated throughout the Mediterranean region. The reasons for this lie in Athens' democratic structure and its trading power. Only Alexander the Great introduced a new significant currency, which ended Athens' supremacy.

Rome

As in ancient Greece, there were also different forms of money in Rome. A standardization towards a generally valid currency took place around 500 BC. Money was initially used to set penalties. In the course of the expansion of the Roman Empire, ever greater deposits of gold, silver and bronze came to Rome as spoils of war. This encouraged the now emerging large-scale minting of coins. At first, bronze and silver coins were produced. However, it took a relatively long time for Roman coinage to match the scale of Greek coinage. In the course of the Punic Wars, the metal content of the coins was reduced, as ever larger amounts of money were needed to finance the military. On the other hand, the Roman currency also spread more and more throughout Italy, so that all other Italian cities virtually stopped minting coins. In the newly conquered territories outside Italy, countless different currencies existed, but they were convertible with the main Roman currency.

As a result of further expansions, ever greater quantities of silver flowed into Rome, so that a large part of state expenditure was financed by the minting of new silver coins, which in the following centuries initially led to the devaluation of money and in the 3rd century AD to the complete collapse of the Roman silver currency. Increasingly, Roman citizens no longer had confidence in ever new forms of coinage, which tended to have an ever decreasing silver content. The result was that older coins in particular were hoarded or melted down. As a result, money lost much of its importance, so that the pay of Roman soldiers, for example, was paid directly in grain. In response, the emperor Constantine the Great replaced the silver currency with a stable gold currency.

In late antiquity there was finally a reorganization of the monetary system, whereby silver coins were again minted - but this time with a high silver content - as well as bronze coins. Gold coins, however, continued to exist. Regardless, silver coinage nevertheless continued to lose importance, so that Rome's monetary system, once based on silver and bronze coins, was replaced by a system of a gold and bronze currency.

Byzantium

The basis for the Byzantine monetary system was the gold currency introduced under Constantine I, the so-called solidus. It was introduced by the emperor Constantine the Great in 309 in place of the aureus as a new nominal and remained, from the 10th century as histamenon and from the 11th century as hyperpyron, until the conquest of Constantinople (1453) longer than a millennium in circulation. This currency existed for about 1000 years. The reasons for this are the high gold content and the resulting stability of the gold currency. Silver lost more and more importance in the course of this development. However, like bronze money, it continued to exist alongside the gold currency as a means of payment. Money had an enormously high value in Byzantine society. It was used in all areas of the economy as well as for public expenditure and made international trade possible. However, as a result of growing insecurity (including piracy on the trade routes), international trade collapsed almost throughout the Byzantine area.

Early Middle Ages

Following on from the solidus already mentioned, the heavy silver denarius, also called the penny, developed under Charlemagne. However, the circulation of gold within the framework of state institutions per se decreased. On the other hand, money increasingly developed into a medium of exchange that served trade and market activities. The original gold currency became less important as a means of payment and was hoarded only as a store of value. In the 7th to 8th century the transition to the pure silver currency took place, which only had the pure calculation reference to gold.

introduction of paper money

Paper money in the form of banknotes was first used in China. Its introduction was a lengthy and steady process that extended roughly from 618 to 1279. Thus, in the 10th century, paper money initially served only on a very limited regional scale as a convenience for traders in the state-owned salt industry. Banknote production was subsequently nationalized, but there were many regionally distinct currencies. The actual mass production of banknotes was not made possible until the invention of printing with movable type in the 11th century. In the mid-13th century, the many different currencies were unified into one state currency for the first time.

A strong monetary economy developed in the Islamic world during the period from the 7th to the 12th centuries, benefiting from increased trade turnover and a stable high-value currency (the dinar). It was during this period that loans, cheques, promissory notes and savings accounts were first introduced. The necessary banking structures also emerged with this development.

In 1661, banknotes were officially introduced in Sweden for the first time at the European level. Although Sweden had rich copper deposits, copper coins had a low face value, so large and exceptionally heavy coins had to be minted. The use of paper money thus represented an enormous relief.

The use of banknotes naturally revealed many advantages, so that, for example, the granting of credit was noticeably facilitated and the very risky transport of gold and silver was also eliminated. Furthermore, it was now possible for the first time to issue shares in companies in the form of paper.

On the other hand, however, there were some disadvantages, such as the fact that governments were now theoretically able to reprint unlimited amounts of money to cover their financing needs (simplified war financing), since, unlike coins with a precisely defined precious metal content, there was now no longer a fixed deposited value of banknotes. One possible consequence of this development would be the onset of strong inflation.

The paper currency, which was not tied to precious metals, finally gained acceptance in the 20th century - at the latest during the world economic crisis.

transition to national single currencies

In the High Middle Ages, the right to mint coins was a privilege to which every noble aspired, for the right to mint coins was a profitable sovereign right. This led to the fact that there were many non-comparable currencies, where the precious metal content could fluctuate greatly for individual types of coins. This was because in the Middle Ages, kurant coins were common; the exchange value of foreign coins was determined on the basis of their precious metal content. This in turn hindered supra-regional trade. For these two reasons - facilitation of trade and concentration of power - the tendency towards national single currencies increased.

In the early days of curant money, the metal content of the coins corresponded to their nominal value. However, since the mint lords were often tempted to debase coins in order to cover their monetary needs, inflation occurred several times in the early modern period. For example, the so-called Kipper and Wipper periods at the beginning of the Thirty Years' War were based on coin debasement.

The driving force in Europe was France, which, with its central government, collected the coinage rights early on and made them subject to the king. The first important monetary reform was the great coinage reform under Louis XIII in 1640-1641, when the Louis d'or was introduced. The introduction of the French franc in 1795 established the first decimal currency. Napoleon's campaigns spread this currency and especially its decimal denomination throughout Europe. As a result, a number of coinage systems emerged in and around France that were similar in structure and formed fixed exchange rates because of the high purity curant coins. This led to the creation of the Latin Coinage Union on December 23, 1865; it was a monetary union consisting of France, Belgium, Italy, Switzerland, and Greece that gave clear guidelines for coinage. The countries minted their own coins, but all 100 denomination coins (100 francs, 100 francs, 100 lire, 100 drachmas) were made of 32.26 grams of gold and were 35 mm in diameter. The disadvantage of the Latin Monetary Union was bimetallism, i.e. the fixed rate of exchange between gold and silver coins (the term limp currency referred to a monetary system in which two metals (usually gold and silver) were legal tender).

The gold standard

→ Main article: Gold standard

In addition to the sharp fall in the price of silver towards the end of the 19th century, the bimetallic currencies brought further problems with them, so that many states decided to back their currency only with gold. By backing currencies with gold, the disadvantages that the introduction of paper money brought with it (especially with regard to the increased risk of inflation) were to be cushioned. Great Britain was a pioneer in this development and introduced the gold standard as early as 1817. Germany (1871 in the course of the Franco-Prussian War) and the USA (1900) followed. However, there was no general harmonisation, i.e. after 1880 there were various forms of gold currency.

| Foreign exchange reserves in the form of | Predominantly gold coins | Gold, silver, bullion coins, banknotes |

| Gold | England, Germany, France, USA | Belgium, Switzerland |

| mainly foreign exchange | Russia, Australia, South Africa, Egypt | Austria-Hungary, Japan, Holland, Scandinavia, other British dominions |

| foreign-exchange-only | Philippines, India, Latin America |

With the introduction of the gold standard, the so-called "obligation of convertibility" came into being, i.e. it was theoretically possible for every citizen at any time to exchange his cash for the corresponding amount of gold at the central bank. Gold parity here refers to the exchange ratio. This pure gold standard actually existed only in theory. In practice, however, the deposit of the currency with gold functioned only as a kind of hedge against excessive cash inflation (price stabilization).

With the beginning of the First World War, the need for money on the part of governments increased dramatically. This development was intensified during the Great Depression and finally by the outbreak of the Second World War. Many countries now moved away from the pure gold standard and restored it to a gold core standard. The direct exchange of banknotes for gold was thus ruled out.

Bretton Woods and the IMF System

→ Main article: Bretton Woods system

As early as 1944, during the Second World War, 44 countries decided to introduce a new monetary system. According to the White Plan, the core idea was to link international currencies to the US dollar. The US central bank was obliged to exchange the dollar for gold at a certain exchange rate vis-à-vis the central banks of other countries in the Bretton Woods system. This created fixed exchange rates between the respective currencies and the US dollar as the anchor currency.

Furthermore, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank were established. The IMF was to promote the stability of the international monetary system and to correct imbalances. It therefore de facto monitored the fixed exchange rates. The introduction of special drawing rights by the IMF also served this purpose.

The value of the dollar as an anchor currency was to be secured by the fact that the central banks of the participating countries had the right vis-à-vis the Fed to exchange dollars for gold at an exchange rate of $35 per fine ounce. The actual rate of exchange depended on the size of the FED's gold reserves. In 1948, the FED had $25 billion worth of gold reserves (71% of the world's gold reserves), offset by short-term foreign debt of $18.6 billion. After World War II, almost all Bretton Woods countries had large pent-up demand for capital and consumer goods, so they preferred to accumulate dollar stocks rather than exchange dollars for gold. Due to constant trade deficits of the United States, the foreign debt kept increasing. In 1961, the FED still held 44% of the world's gold reserves, but short-term maturing foreign debt was already $1 billion higher than the value of gold reserves. By 1971, US gold reserves had fallen to $12 billion. The central banks of the other Bretton Woods countries had dollar reserves of more than $50 billion in 1971. The system could continue to function only as long as the Bretton Woods countries were willing to hold large dollar reserves without exchanging them for gold. In the early 1970s, the Bretton Woods Agreement was abandoned, but the institutions continued to exist, sometimes with altered responsibilities.

The system of flexible exchange rates

At the beginning of 1973, dollar exchange rates were liberalized in most Western European countries and in Japan. Exchange rates became flexible. This gave rise to the concept of free floating, which contrasted with fixed exchange rates. However, smaller economies in particular, which were more dependent on international trade than, for example, Japan or the USA, decided to keep fixed exchange rates. This became increasingly difficult over time as international capital movements became easier and faster due to new developments in computer technology and telecommunications. In addition, control also became more difficult.

Shortly after the introduction of flexible exchange rates, the new system was confronted with two oil price shocks. This resulted in substantial current account surpluses (OPEC countries) and deficits (OECD countries). However, this evened out again in the medium term.

It was not until the 2nd IMF Amendment Agreement that the choice of exchange rate system was left to the member states themselves. However, this was tied to the obligation of the individual states to ensure stable monetary and economic conditions. Gold thus finally lost its position as a reference value.

Exchange rates subsequently fluctuated noticeably and also changed permanently. In particular, the interdependent states in Western Europe tried to jointly hedge against exchange rate fluctuations and created the European Monetary System (EMS) for this purpose. They aimed for stable exchange rates on the basis of graduated flexibility.

The flexible exchange rates benefited international trade in particular, which grew disproportionately compared to the development of gross domestic products.

However, no general trend in the development of inflation could be identified. Inflation rates in Germany and the USA diverged significantly.

The Mount Washington Hotel 2003, site of the Bretton Woods Conference 1944

Swedish banknote, 1666

Regensburg penny from the 10th century.

Solidus Constantine I.

Marble statue of Constantine I in the Musei Capitolini, Rome

Tetradrachmon Macedonia, Alexander the Great 336-325 BC, showing Heracles with the lion skin

Questions and Answers

Q: What is currency?

A: Currency is the unit of money used by the people of a country or Union for buying and selling goods and services.

Q: What does it mean when a currency is pegged or fixed?

A: When a currency is pegged or fixed, it means that it has a constant value compared to what it is pegged to, usually another currency.

Q: What is an example of a pegged currency?

A: An example of a pegged currency is the Cape Verdian escudo, which is pegged to the Euro.

Q: How does a fixed or pegged currency value change?

A: If the value of the currency that a fixed or pegged currency is pegged to goes up 1% compared to another form of currency, the value of the fixed or pegged currency also goes up 1% compared to that same currency.

Q: What did many countries use as the basis for their pegged or fixed currency before the 20th century?

A: Many countries used either gold or silver as the basis for their pegged or fixed currency before the 20th century.

Q: What was the term for the system where a currency was pegged to a commodity such as gold or silver?

A: The term for the system where a currency was pegged to a commodity such as gold or silver was the "gold standard" or "silver standard".

Q: When did most countries stop using silver and gold standards?

A: Most countries stopped using silver and gold standards in the 20th century.

Search within the encyclopedia