Crocodilia

![]()

Crocodile is a redirect to this article. For other meanings, see Crocodile (disambiguation).

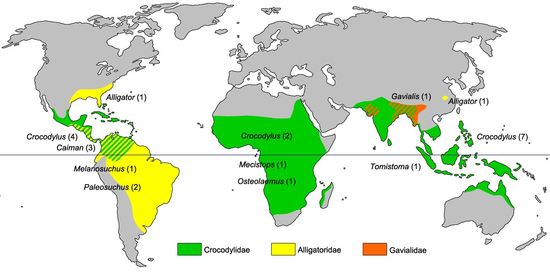

The crocodilians (Crocodylia; ancient Greek κροκόδειλος, "crocodile") are an order of amniotic terrestrial vertebrates. Today, about 25 species are distinguished, divided among 8 to 9 genera in the three families of the true crocodiles, the alligators (including caimans), and the gavials. In a more specific sense, the term "crocodiles" is also applied to the true crocodiles.

Crocodiles live in rivers and lakes of the tropics and subtropics, only the saltwater crocodile can also live in the sea and is often found on the coasts of Australia and various islands of Southeast Asia. Their lizard-like, primal appearance is just one of many adaptations to their lifestyle as aquatic lurking hunters. They have a laterally flattened tail that helps them swim quickly. They also have raised eyes and nostrils, allowing them to be almost completely submerged while still being able to breathe and look out of the water.

Along with birds, crocodilians are one of the two extant (recent) taxa of archosaurs, which include the extinct pterosaurs and the non-bird dinosaurs (see outer systematics). However, modern crocodilians have only a fraction of the species diversity of birds. The relatively close relationship between birds and crocodiles can be demonstrated by a whole range of features, most notably the construction of the cardiovascular system.

Due to a back-armor from bone-plates lying in the skin, the crocodiles are also called armored-lizards colloquially.

Features

General

The physique of today's crocodiles as well as their physiology are very strongly influenced by the way of life in the water. These characteristics include the flat physique with the mostly broad and flat snout as well as the tail, which is formed into a rudder and flattened at the sides. Crocodiles are very large animals compared to most other recent "reptiles" and reach body lengths of 1.20 meters to 6.70 meters depending on the species. The body weight is proportional to the body length to approximately the third power, so that the small species weigh considerably less than 100 kilograms, while the large species can reach more than 1000 kilograms. Fossil species even reached body lengths of over twelve meters and a correspondingly much higher weight (possibly more than 10 tons). Crocodiles grow for almost a lifetime, but the speed of growth decreases significantly with age, so that the annual increase in length of older crocodiles is only a few centimeters.

Skull

The skull of crocodiles is, compared to that of many other reptiles, relatively elongated, in some forms even extremely elongated. The major part of the skull (usually more than two thirds) is occupied by the snout. Depending on the way of feeding, the snouts of the different species differ in length and width. For example, most species have a rather unspecialized, relatively broad snout that allows them to use a wide range of food. Species such as the Ganges gavial (Gavialis gangeticus) and the Sunda gavial (Tomistoma schlegelii), which are specialized in catching fish, on the other hand, have a very narrow, elongated snout.

The eye sockets of crocodiles have migrated up the skull in the course of evolution and the eyes stand out clearly from the forehead in the living animal. The bony external nasal openings have fused into a single opening, as in mammals. This is oval, lies far forward on the snout, and is connected with the pharynx by a long system of canals separated from the oral cavity by a secondary roof of the mouth, so that the animals can breathe without difficulty even when their mouths are full or immersed in water. The anterior portion of the secondary roof of the mouth is formed by the maxillary bones. This also parallels the anatomy of mammals.

As in other representatives of the archosaurs and the diapsids in general, the skull has two temporal windows on both sides. The posterior upper cranium in crocodilians, unlike in many other diapsids, is table-like-flat and consists of thick-walled bone. The upper temporal windows form roundish openings in this "skull table" and are not separated from the lower temporal windows by narrow bony ridges, as is the case in lizards, for example, but are clearly set off from them. The lower temporal window lies, slightly hidden by the laterally overhanging "skull table", behind the eye opening (orbita) in the lateral wall of the skull. Overall, the skull is rather compactly built. Apart from the temporomandibular joint, it has no parts that move against each other (akinetic skull). On the upper side of the snout, on the posterior upper cranial roof and on the outer side of the lower jaw, the bone surface is sculpted like a honeycomb, which is related to the fact that the bone is firmly fused with the overlying skin (integument) in these places.

The posterior region of the outer lateral wall of the mandible is also characterized by a conspicuous oval opening, the so-called mandibular window. The posterior end of the mandible has an outgrowth, the retroarticular process, which makes the mandible longer overall than the top of the skull (cranium) and extends well beyond the occiput. The retroarticular process serves as a lever and attachment for the muscles to open (lower) the lower jaw.

Dentures

The attachment of the cone-shaped, single-pointed teeth in the jaw-bone is thecodont, that is, the tooth-"roots" sit, as with the mammals, in tooth-fans (Alveolen) and are fastened in it by means of connective-tissue.

Significant differences with regard to the organization of the dentition exist especially between the three families of crocodiles. The dentition of crocodiles, as is common for "lower" tetrapods and unlike almost all mammals, is in principle homodont, that is, all teeth have the same shape. However, in true crocodiles (Crocodylidae) and alligators (Alligatoridae), the teeth are not all the same size. Therefore, the dentition of these two groups is called pseudoheterodont. The margins of the maxilla are wavy, both in the longitudinal vertical plane (sagittal plane) and in the horizontal plane (frontal plane), which is called festooning. The largest teeth sit on the "crests" of each wave, further emphasizing the pseudoheterodonty. The margins of the mandibles are also festooned. "Wave crests" and largest teeth are located where the "wave troughs" are in the maxilla. One of these largest teeth is the fourth mandibular tooth. In the true alligators (Alligatorinae), the festooning is less pronounced than in the true crocodilians, and all of the mandibular teeth are inside (on the tongue side) of the maxillary tooth row when the mouth is closed and cannot be seen from the outside. The crown of the fourth mandibular tooth then lies in a pit of the maxillary bone. In the true crocodiles, due to the horizontal festooning, the teeth of the lower jaw lie partly on the tongue side and partly on the cheek side of the teeth of the upper jaw when the mouth is closed, and are therefore partly visible from the outside. The fourth lower jaw tooth thereby engages a particularly deep, notch-like "trough" of the upper jaw. In caimans (Caimaninae), the festooning is less pronounced than in crocodilians, but more pronounced than in true alligators. In the Gavials (Gavialidae) the snout is very narrow, greatly elongated, and not festooned except in the most anterior part. The teeth are relatively long and thin, about all of the same size (homodonty in the true sense) and inclined on the cheek side. This is called a cage dentition.

Crocodilian dentitions, like the dentitions of most vertebrates, undergo multiple, regular tooth replacement (polyphyodonty), with replacement teeth developing in the sockets of functional ("active") teeth. In older animals, each tooth is replaced once a year; in younger animals, more often. It is estimated that over the lifetime of a four-meter-long individual, each tooth is replaced up to 50 times. However, as animals age, tooth replacement occurs less frequently and eventually stops altogether, so that in very old animals the crowns of the teeth may be worn down to the jaws.

Bone armor

Crocodiles owe their name armored lizards to their hard scale armor, which extends over the entire torso, tail and extremities. The uppermost skin layer, the cornea (stratum corneum), consists of an alternating number of layers of collagen fibres. Crocodile embryos have two to three of these layers. As they age, more layers accumulate underneath, so that in an adult Mississippi alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) there may be as many as 24 layers on top of each other. Crocodiles do not shed their skin; new layers are compensated for by abrasion of the outer layers.

The scales on the back are particularly large and strongly developed and are therefore also called dorsal shields. They are keeled and reinforced by bony plates (osteoderms), which are also keeled. Depending on the species, four to ten adjacent plates form a transverse row and each transverse row corresponds to a vertebra of the vertebral column. Also the shields in the neck of the animals, the nuchal plates, are underlaid with osteoderms and form species-typical patterns. The ventral shields of most species are unkeeled-flat and quadrangular, and only in a few species are they reinforced by osteoderms. On the tail, the transverse rows of the dorsal and ventral shields touch, forming transverse rings. The upper side of the tail bears a paired scaly crest, which changes into a single scaly crest towards the tip of the tail. Especially in smaller species, such as the smooth-fronted caiman (genus Paleosuchus), the stump crocodile (Osteolaemus tetraspis) and the black caiman (Melanosuchus niger), the scales on the extremities, neck and even eyelids are also provided with osteoderms. On the eyelids, these are called palpebralia. Larger species such as the inguinal crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) protect themselves primarily by their size and their scales have significantly fewer osteoderms.

Axial skeleton and extremities

The spine of all crocodiles consists of nine cervical and 17 trunk vertebrae, which are followed by the tail with 35 to 37 individual vertebrae. The torso vertebrae can in turn be divided into eight thoracic, seven lumbar and two sacral vertebrae. All vertebrae are so-called "procoele vertebrae", i.e. vertebral bodies which have a cavity at the front end into which the next vertebra in front engages. Exceptions are the atlas, the epistropheus as well as the central sacral vertebra and the first caudal vertebra. Crocodilians have ribs along the entire trunk spine up to the first caudal vertebrae, and they also have abdominal ribs (gastralia) without attachment to the spine. The sternum is cartilaginous.

The shoulder girdle has a simple structure and essentially corresponds to the basic structural plan of the tetrapods. The clavicles are absent, allowing greater freedom of movement. Of interest is the pelvis, which is similar in structure to that of mammals and, because of the alignment of the pubic and ischial bones, gives evidence of an originally bipedal mode of locomotion. The forelimbs terminate in a five-fingered hand, of which only the medial three fingers bear claws. Webbed toes are developed between the four toes of the hind limbs. The outermost (lateral) toe also lacks a claw.

Breathing and circulation

Various organ systems, especially the respiratory and circulatory systems, are particularly adapted to the amphibious way of life. This concerns, among other things, the construction of the nose: the nostrils lie far forward and elevated on the snout, the nasal cavity is almost completely isolated from the oral cavity by the bony secondary roof of the mouth, and the internal nasal openings (choanas) lie far back and open into the pharynx. This nasal structure allows crocodilians to breathe even when almost completely submerged, needing only to hold the tip of the snout out of the water. A fleshy soft palate closes the pharynx against the mouth when the mouth is open underwater, preventing water from entering the trachea. The secondary roof of the mouth also allows crocodiles to breathe while holding onto a larger prey animal with their jaws and waiting for it to give up its resistance. The lungs are very voluminous, divided into several pouch-like individual chambers, and are ventilated by muscular movement of the thoracic cavity and by a septum similar to the diaphragm.

Like all amniotes, crocodiles have a four-chambered heart with two main chambers and two atria. The ventricular septum completely separates the two main chambers (ventricles), just as it does in birds and mammals. Unlike mammals and birds, however, crocodilians, like all other reptiles, have two aortas (body arteries), one right and one left. The left aorta, along with the pulmonary artery, originates in the right ventricle. The right aorta, from which the arteries supplying the head region (carotids) branch off, arises from the left ventricle. Above the aortic root is the so-called foramen panizzae, a small opening between the left and right aorta.

This breakthrough fulfils two main functions. On the one hand, during normal breathing, it ensures that the left aorta also receives oxygen-rich blood and thus carries mixed blood into the torso to the organs (so-called right-left shunt), and on the other hand, during longer dives, it takes over the pressure equalisation between the right and left ventricles or the left and right aortic roots (left-right shunt). left and right aortic roots (left-right shunt), because the pressure in the right ventricle or left aortic trunk is higher during these periods, despite a greatly reduced heart rate, because the pulmonary artery narrows considerably. Since the lungs are filled with air before the dive, relatively oxygen-rich blood is still transported via the pulmonary circulation into the left half of the heart and from there into the right aorta, so that the brain and the sensory organs in the head region are sufficiently supplied with oxygen, while only oxygen-poor blood is transported via the left aorta.

The four-chambered structure of the heart with a completely closed ventricular septum is considered an important indication that crocodiles are more closely related to birds than to any other reptile.

Crocodile, Forefoot

.jpg)

With the real alligators (Alligatorinae), here a Mississippi alligator, all lower jaw-teeth lie within (tongue-sided) the upper jaw-teeth-row.

Crocodile forms (historical representation from 1907)

Skull of an adult representative of a large Crocodylus species with clearly recognizable ornamentation, unpaired nasal opening and distinct retroarticular processes on the lower jaw.

In the true crocodiles (Crocodylidae), here a Nile crocodile, the large lower teeth lie outside (cheek-side) of the row of teeth of the upper jaw. This is particularly clear in the fourth and largest mandibular tooth.

Lifestyle

Habitats

All crocodiles living today are adapted to an amphibious lifestyle in their physique and way of life, spending the majority of their time in water. With one exception, the inguinal crocodile, they all live predominantly in freshwater, but can also be found in brackish water or coastal saltwater. There are species that prefer open waters such as lakes and larger rivers, as well as species that live in streams and in the undergrowth. Their range is restricted to the tropical areas, only the two alligator species live in areas with light winters in their northern range. In addition to these characteristics, their occurrence also depends on the food supply, the availability of breeding sites, the competitive situation and hunting by the local population.

Hunting behaviour

All crocodiles are primarily carnivores. Most species hunt very unspecifically any kind of prey that they can overpower with their size. The very narrow-snouted species with teeth like those of the Ganges gavial, Sunda gavial and Australian crocodile, which prey mainly on fish, are particularly specialized in a range of prey. Juveniles and smaller species hunt mainly insects, frogs and small mammals, while the adult representatives of the larger species attack everything they can reach. Cannibalism, especially on young animals, is also not uncommon. Despite their sluggish appearance, crocodiles react extremely quickly and also act very skillfully on land.

Crocodiles are effective hunters, lying largely submerged in the water for most of the often nocturnal hunt (ambush hunters). They are capable of approaching the shore silently and darting out of the water. In doing so, they use their extremely powerful tail for propulsion. When holding the prey, the conical teeth bore into the victim, and when biting, the extremely strong jaw muscles develop an enormous biting force, which usually makes escape impossible. Once they have captured a victim, they pull it under water to drown it. According to projections from extensive stomach analyses, an adult Nile crocodile probably eats only 50 full meals a year, thus capturing only about one prey animal per week. Mississippi alligators, on the other hand, hunt more frequently, but usually prey only on smaller prey.

In order to tear off pieces of meat, they grab the victim with their teeth and turn themselves around their own axis several times. In doing so, they tear their prey in the places where they have left a perforation with their teeth. To facilitate the dismemberment of the prey, they often hide the carcass for a few days to soften it. Crocodiles are unable to chew food, so they swallow torn-off pieces of meat whole. They often have gastroliths, but their function has not yet been completely clarified. According to the two best-known hypotheses, these stones in the stomach serve either to crush the food or as ballast to reduce buoyancy in the water.

As a scientific study published in July 2013 found, 13 of 18 crocodile species studied, including the Nile crocodile and Mississippi alligator, also regularly consumed fruits, nuts and seeds.

Reproduction and social behaviour

Crocodiles lay between 20 and 80 eggs in nests, depending on the species and nest size. Two types of nests can be distinguished:

- Mound nests are piled up from plant-material, in which the necessary brood-heat originates through fermentation.

- Pit nests are self-dug depressions in which the eggs are covered with soil material or a mixture of soil and plants.

Crocodile eggs have a relatively firm calcareous shell and are more similar to bird eggs than to the eggs of most pangolins. They are thus well protected both against water absorption from the outside and against excessive water loss.

The development of crocodiles depends on the temperature in the nest (temperature-dependent sex determination). They do not have sex chromosomes, so that potentially both sexes can develop from the eggs. If the eggs are hatched below about 30°C, they will hatch into females; if the temperature is around 34°C, they will hatch into males only. If the eggs are buried at different depths, there is a high probability that both sexes will develop.

As adults, crocodiles have no natural enemies, but their young are preyed upon by birds, monitor lizards or even members of their own species. Thus, it is believed that about 90 percent of crocodiles are preyed upon as embryos or juveniles by nest predators or predators. Nest predators include monitor lizards, mammals such as the raccoon and pigs, and birds such as the African marabou. In addition, embryos can die from climatic conditions such as cold or from fungus on the eggs. Young can be preyed upon by birds of prey and herons.

Eggs and young are guarded by the mother in many species to protect them from predators. The mother can also help her young to hatch as soon as they make themselves audibly heard. Afterwards, the mother often even carries her young into the water and fends off potential predators.

Life expectancy

Knowledge about how old crocodiles can become is currently still very limited. Data on crocodiles that certainly died of natural causes come exclusively from zoological gardens, although the exact year of birth was known for only a few animals. It is also unclear whether crocodiles in zoos live longer than their wild counterparts due to medical care and permanent food supply, or whether they die earlier due to visitor stress and living in an artificial habitat. Wild crocodiles are dated by the growth plates on their long bones or their osteoderms (skeletochronology), but this method is subject to certain uncertainties.

For smaller species (e.g. the caimans) in captivity, maximum ages of 20 to 30 years are given. Larger species, such as the saltwater crocodile, can live up to 70 years. The oldest crocodile in the world to die in human care is said to have lived to be 115 years old.

A female alligator with offspring in Everglades National Park, Florida.

Crocodile caiman (Caiman crocodilus) with a captured piranha.

Distribution of representatives of the three families of crocodiles.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is Crocodilia?

A: Crocodilia is an order of Archosaur reptiles.

Q: How many living families are there in Crocodilia?

A: There are three living families in Crocodilia.

Q: What is the relation between birds and Crocodilians?

A: Crocodilians are the nearest living relatives to birds, because they are both survivors of the Archosaurs.

Q: When were Crocodilians first found?

A: Crocodilians were first found in the Upper Cretaceous period.

Q: What were Crocodylomorphs?

A: Crocodylomorphs were a wider group of Archosaurs that were slender land-living forms in the Upper Triassic, and the sister group of the dinosaurs.

Q: What is the relation between Crocodylomorphs and Crocodilians?

A: Crocodilians are descended from the Crocodylomorphs.

Q: What is Crurotarsi?

A: Crurotarsi is an even larger group than Crocodylomorphs, which are first seen early in the Triassic.

Search within the encyclopedia