Crito

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Kriton (disambiguation).

The Kriton (ancient Greek Κρίτων Krítōn) is a work written in dialogue form by the Greek philosopher Plato. The content is formed by a fictional conversation in literary form. Plato's teacher Socrates is discussing with his friend and pupil Kriton, after whom the dialogue is named.

Socrates has been sentenced to death for asebie (impiety) and seducing the youth. He is in prison awaiting his imminent execution. Kriton visits him in order to persuade him to escape. Socrates, however, rejects the proposal. He explains his decision in detail. It is based on the philosophical principles he professes: conventional views are irrelevant, only reason is decisive, and justice must be the guiding principle under all circumstances. One must not repay injustice with injustice and generally do no wrong; obligations must be kept. These principles are more important than saving one's life. Nor may a citizen evade an unjust court judgment, for otherwise he would deny the validity of the laws and thus the basis of orderly coexistence in the state, which would be an injustice. It would be a violation of the citizen's duty of loyalty to the state community. Kriton cannot reply to Socrates' arguments.

In ancient studies, but also in modern philosophical debates, the unconditional obedience to the law, which is the theme of the Criton, is controversially discussed. In philosophical discourse, the issue is the conflict of conscience that arises when a valid legal norm compels one to behave in a way that, from the point of view of an affected person, constitutes a manifest grave injustice. In research on the history of philosophy, the question of whether the Criton should be understood as a plea for unconditional obedience is answered differently; "authoritarian" models of interpretation compete with "liberal" ones. Opinions differ about the validity of the argumentation in the dialogue.

The beginning of the Kriton in the oldest surviving medieval manuscript, the Codex Clarkianus, written in 895.

Place, time and participants

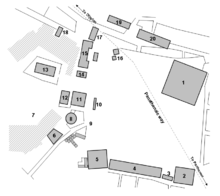

The conversation, whose literary representation is possibly based on a historical event, takes place in the prison of Athens in 399 BC. Socrates has been imprisoned there since the death sentence was passed on him about four weeks ago. The execution is expected to take place on the next day or the day after. The location of the prison cannot be determined with certainty. It was probably located near the court of Heliaia, according to excavation results probably about 100 meters southwest of this building, just outside the grounds of the agora.

Plato paints a true-to-life picture of his revered teacher Socrates. However, since this is a literary work, it should always be noted that the views and arguments that Plato puts into the mouth of his dialogue figure need not be identical to those of the historical Socrates.

The philosopher's only interlocutor, his friend and peer Kriton, was a historical figure. He was a wealthy Athenian who, like Socrates, came from the demos Alopeke. When Socrates was accused, Kriton unsuccessfully offered to vouch for its payment if a fine was imposed. After the death sentence, he was prepared to stand surety with the court that Socrates would not escape. In this way he hoped to spare his friend a stay in prison, but this proposal was also rejected. At both the trial and the execution, Kriton was among those present.

Plato also lets Kriton appear in other dialogues - in the Euthydemos and the Phaidon. It is striking that Kriton, as a conventionally thinking Athenian, remains alien to the philosophy of Socrates, whom he personally holds in high esteem, despite his sincere efforts.

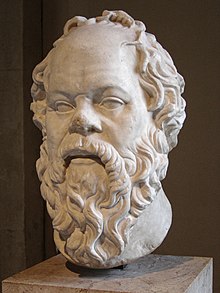

Socrates (Roman bust, 1st century, Louvre, Paris)

The Agora of Athens; the prison was probably located about 100 meters southwest of the building marked No. 5.

Content

The proposal and the arguments of Kriton

Kriton has gone to the prison very early, long before daybreak and before the beginning of the regular visiting hours. With special permission of the jailer he has entered; silently he has seated himself beside the sleeping philosopher. Meanwhile dawn has broken, Socrates has awakened, and expresses surprise at seeing his friend so early. Kriton explains that he did not want to wake him prematurely. He expresses his amazement at the ease with which Socrates takes his fate upon himself. The latter points out that at his age - he is seventy - it would be inappropriate to be unwilling about death, which is approaching anyway.

The reason for the early coming of the visitor is the imminent execution of the prisoner. Kriton expects it for the following day, Socrates for the day after next. For Kriton, who wants to persuade his friend to escape the next night, time is therefore pressing. He has already devised a plan of escape and intends to accomplish it by bribing the prison guards. In doing so, he assumes that his fortune will be sufficient; however, should this not be the case, many other friends are willing to provide the required sum. Thanks to this broad willingness to help, Kriton assures us, it is not necessary for any individual to ruin himself financially. In Thessaly, Kriton has friends who hold Socrates in high esteem and who gladly take him in and ensure his safety.

Kriton fears to lose a friend as he will never find one again. With several arguments he tries to convince Socrates. He thinks it is the duty of friends to sacrifice their property in such a situation; therefore Socrates can accept the offer without hesitation. In the event of execution, Kriton fears ill-repute; he thinks that the philosopher's friends will then be accused of having failed to save him out of stinginess and cowardice. Criton does not wish to expose himself to such reproaches. Moreover, he finds it unjust that Socrates, in going to his death, fulfills the will of his enemies. Furthermore, Kriton argues that a father bears responsibility for his still young children. He who has fathered children like Socrates must take care of their upbringing and not abandon them and leave them to the fate of orphans.

The theoretical premises of Socrates' argumentation

After Kriton has presented, explained and justified his proposal, Socrates goes into it in detail. He wants to have an open discussion and asks Kriton to express objections if necessary. Kriton, however, does not raise any objections to the following remarks, for his friend's argumentation seems conclusive to him. He only listens and expresses his agreement with the individual lines of thought or says that he has not understood something.

First, Socrates reminds us of the principle that only objective, rational consideration may determine a decision. If subjective fears or needs oppose what is found to be right, they must not be allowed any influence, otherwise one is not in accord with one's principles. Also irrelevant is the fact that some opinions are widely held, for what is important is not the number but only the competence of the representatives of a view. Just as an athlete follows only the advice of physical education instructors and doctors and not that of a crowd of ignorant people, because otherwise he would damage his body, so too in matters of right and wrong, good and bad action, only informed judgment is relevant. The opinions of the ignorant crowd do not count.

For those who have treated their bodies wrongly out of incompetence and have thus broken down their health, continuing to live no longer seems worthwhile. But there is also another kind of disruption. It concerns that in man - "whatever it may be" - to which justice and injustice refer. By this paraphrase Socrates means the immortal soul. It is, according to his conviction, damaged by unjust action. After such disruption, life is no longer worth living for the philosopher. Since the soul is far nobler and more important than the body, its damage is far worse than physical impairment and also worse than death. It is not life itself that is worth striving for, but only a good life. To live well is to live virtuously, that is, to be always just. Criton agrees with this. Thus, the question of whether escape from prison is appropriate for a wrongfully convicted person can only be examined and resolved from the perspective of justice.

Criton's considerations about the financial aspect, about a possible damage of reputation and about the education of the children are not taken seriously by Socrates. Such considerations are inconsequential to him. He compares such motives to the impulses of irrational people who carelessly condemn someone to death and would later gladly undo their deed, if that were possible.

Socrates reminds his friend of their common convictions, which they agreed upon long ago and to which they have always adhered ever since. It would be absurd to simply drop these well thought-out principles now at an advanced age, as if they had been mere childish ideas. The starting point is the conviction that, under all circumstances without exception, it is wrong in principle to do something wrong. By wrong Socrates understands everything that harms someone. He considers harming to be absolutely wrong even if it is in retaliation for a wrong one has suffered oneself, such as insulting an insulter. Another principle is that a commitment to something just that one has made must be kept at all costs. Kriton reaffirms his earlier commitment to these principles.

The application of the theory to the current case

As Socrates subsequently sets out, the question now to be examined is whether by fleeing he would harm someone or disregard a just obligation. To this end, he recites what he believes the laws would say if they could speak and justify their claim to validity. He lets the personified laws take the floor and represent the position of the state, as would a speaker who had to defend legality.

The laws would assert that without respect for their rules the state community could not exist. They would ask a Socrates acting in Kriton's sense whether he wanted to ruin the state by granting himself, and thus every citizen, the right to disregard legally binding court decisions according to his personal discretion.

To this Kriton - or Socrates, if he agreed with Kriton - could reply that he does not oppose the entire legal system, but only a judgment of injustice. But then the question would have to be addressed to him, what he had to reproach his hometown, whose legal system he undermined with his behavior. Socrates, if he behaved in this way, would have to be reminded of the basis of his existence: It would then have to be held against him that the existence of the state order had been the precondition for his father being able to marry his mother. Thanks to this order he had been born, within its framework he had been well brought up. He owed to the laws, like every Athenian, everything good that a legal order could provide for citizens. Therefore, the fatherland with its laws was, as it were, a father to him and, even more than a father, was entitled to his reverence and loyalty. He who disapproved of the conditions and laws in Athens could emigrate with all his possessions. But he who remained implicitly entered into an agreement with the state by which he pledged himself to law-abidingness. If he considers something in the judicial system to be wrong, it is up to him to point out the injustice by argument; if he is not in a position to do so, he has to respect the applicable law. This was especially true of Socrates, he argued, because he had spent his entire life in Athens, preferring that place to any other, even to the states he was wont to praise. He had also demonstrated his acquiescence to Athenian living conditions by founding his family in his hometown. Moreover, in his trial he had rejected banishment as a possible alternative to execution, explicitly preferring death to it. If he had wanted to, he could have chosen exile during the trial and then left Athens legally. A retrospective attempt to unilaterally reverse a free and binding decision was disgraceful.

Furthermore, the laws argue against Criton's opinion that Socrates, if he accepted the offer, would expose his helpers to the danger of also having to flee or forfeiting their fortune. In addition, as a fugitive lawbreaker in a well-established state, he would be suspect to the well-meaning, for he would be suspected of disobeying the laws there as well. So he would have to make do with a place like Thessaly, where disorder and licentiousness reigned. There he might excite mirth with the story of his miserable escape. But as a philosopher unfaithful to his principles, he would be so discredited that he would have to give up his previous purpose in life, philosophical dialogue. Then his meaning in life would consist only in eating. His children, if he did not want to abandon them, he would have to take with him to Thessaly, where they would be homeless. If, on the other hand, he left them in Athens, their good education by his friends would be guaranteed, but his survival would be of no use to them.

In conclusion, the laws recite an urgent admonition: If Socrates now dies, he departs from life as one who has been wronged by men-not by the laws. But if he flees, he in turn becomes a wrong-doer against himself, against his friends, his fatherland, and the laws. Then, as a wrongdoer, bad things await him in Hades, the realm of the dead.

After Socrates has finished the imaginary plea of the laws, he confesses to be as moved by it himself as a cult dancer intoxicated by the sound of flute music, a corybant. Nevertheless, he invites Kriton to express any counter-arguments. Kriton, however, knows nothing to object to, and Socrates ends the conversation by referring to the divine guidance in which he wants to entrust himself.

Questions and Answers

Q: Who wrote the dialogue Crito?

A: Plato, an ancient Greek writer and philosopher, wrote the dialogue Crito.

Q: Who are the only characters in the dialogue Crito?

A: The only characters in the dialogue Crito are Socrates and Crito.

Q: What is the central topic of the dialogue Crito?

A: The central topic of the dialogue Crito is the moral consequences of helping Socrates escape from prison.

Q: What does Socrates argue against in the dialogue Crito?

A: Socrates argues against defying the law in the dialogue Crito, even though Crito is willing to help him.

Q: Does Socrates eventually convince Crito to help him escape from prison?

A: No, Socrates convinces Crito that morally, he must stay in prison and accept his execution.

Q: Who wrote the dialogue Crito among many other works?

A: Plato, who had been a student of Socrates, wrote the dialogue Crito among many others.

Q: How did Socrates die in real life?

A: Socrates died in real life by drinking hemlock.

Search within the encyclopedia