Crimean War

Crimean War

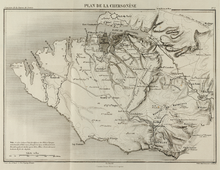

Most important theatres of the Crimean War: Crimea, the coast of southern Russia, the northern coast of Turkey and the Danubian Principalities

Crimean War (1853-1856)

Oltenița - Achalziche - Başgedikler - Sinope - Cetate - Silistra - Nigojeti - Cholok - Odessa - Kurekdere - Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky - Alma - Sevastopol - Bomarsund - Balaklava - Inkerman - Yevpatoriya - Taganrog - Çorğun - Kars - Chernaya - Malakov - Kinburn - Paris Peace

The Crimean War (also Oriental War; Russian Восточная война, Крымская война Vostochnaya voyna, Krymskaya voyna or 9th Turkish-Russian War) was a military conflict lasting from 1853 to 1856 between Russia on the one hand and the Ottoman Empire and its allies France, Great Britain and, from 1855, Sardinia-Piedmont on the other. It began as the ninth Russo-Turkish War, in which the Western European powers intervened to prevent Russia's territorial expansion at the expense of the weakened Ottoman Empire.

Background

Between the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1853, there was a prolonged period in which the great powers of Russia, Great Britain, France, Austria and Prussia avoided waging war against each other. Rather, they formed what has been described as a "European Concert of Powers".

According to historian Jürgen Osterhammel, the Crimean War came about less purposefully than the later Sardinian War or the German Wars of Unification after a chain of diplomatic mistakes, misunderstandings and enemy perceptions. In a wide variety of systems, both autocratic Russia and more liberal Britain, there had been war promoters at work, in Russia, for example, an "ill-informed" tsar and in France "a political harebrain." However, there was also "a logic of geopolitical and economic interests". At its core, it was a conflict between the two powers, Britain and Russia, which had interests in Asia, and it revealed the military weakness of both. "For the first time since 1815, war was accepted to the extent that it actually happened."

Several independence movements, including one in Egypt under Muhammad Ali Pasha, weakened the Ottoman Empire in the 1830s. In 1833, Egyptian forces under Ali Pasha had conquered Syria and threatened Constantinople. The Russian Tsar then formed an alliance with the Turkish Sultan and sent troops, which alarmed Britain, as they saw this as an attempt by the land power Russia to gain military strategic access to the Mediterranean.

The Egyptian troops had to retreat to Syria. In 1839 the Middle East problem became acute again when the Sultan asserted his claims in Syria and attacked the Egyptian troops there. France sided with Egypt, while Palmerston, then British foreign secretary, arranged for Austria, Russia, and Prussia to intervene in the Sultan's favor. The Oriental Crisis ensued, with European powers intervening in the conflict between the Ottoman Empire and Egypt, which was formally part of the Ottoman Empire, in 1839-1841. The Egyptian army commander gave up Syria, which limited France's ambitions in the Orient. With the Dardanelles Treaty of 1841, the Ottoman Empire undertook to close the straits to warships in peacetime. This pushed back the influence of Russia, which had previously been able to threaten British access from the Middle East to India.

Protectorate of the Tsar over the Holy Land

→ Main article: Church of the Holy Sepulchre

A significant cause of the war was religious conflict over the use of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Until then, the claim to ownership of this site, which is considered holy by Christianity, had been shared by the followers of the various Christian denominations. Since the beginning of the 19th century, however, the Greek Orthodox Christians had expanded their position in the use of the church. The Catholics, with the support of Napoleon III, proclaimed Emperor of France in December 1852, now tried to change this situation.

The decisive incident was the removal of the silver star in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem in 1847. Although the High Gate under Sultan Abdülmecid I replaced the star in 1852, it could not prevent the Russian Tsar Nicholas I from demanding the protectorate over all Christians in the Holy Land (the region of Palestine), i.e. sole patronage, in order to protect the Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman Sultan as the political representative of the interests of Islam and the French Emperor - representing the interests of Catholicism - were in no way willing to agree to Russian domination over the Christians in Palestine.

France showed a strong determination to oppose further Russian expansion. Conflict with the government in St. Petersburg, however, was only superficially about the holy places. Jerusalem and other cities of the Holy Land were predominantly inhabited by Muslims and Jews, who at that time still coexisted peacefully. The Christian minorities, of all people, were strongly divided there. Especially at Easter there were fierce conflicts between the Greek Orthodox monks and the Catholic Franciscans. Already at that time the term "monks' quarrel" was used for it. It was about things like who was allowed to repair the Church of the Holy Sepulchre or who was allowed to keep the key to the Church and Grotto of the Nativity. Russia stood behind the claims of the Orthodox, France distinguished itself as the advocate of the Catholics, and Napoleon III tried to continue to base himself and his weak regime on his support among the Catholics in his own country. The mobilization of society for the Crimean War was intended to help the French supporters of the Revolution reconcile with their Catholic despisers, who were equally represented in the population.

For Britain's elites, apart from pretended religious motivation, there was no doubt that a war against the Tsar was generally a war for English values of fair play and the values of the free world, such as the separation of powers and free trade.

Later in the war, there was a widespread public perception that the two Christian nations of France and Britain, ostensibly out of concern for the holy sites, had allied with a Muslim state against Christian Russia.

The Russia expert Orlando Figes calls this war the "last crusade" in the context of the long sequence of military conflicts of this kind, which certainly show parallels to this one. All crusades on the part of the "Christian West" were without exception strategically, religiously and economically motivated wars between 1095/99 and the 13th century. In the narrower sense, however, among the crusades only the Oriental crusades conducted during this period are considered as such, which were directed against the Muslim states in the Middle East. Already after the First Crusade, the term "crusade" was extended to other military conflicts whose goal was not the Holy Land and was applied until modern times, among other things, to very different military actions.

The "sick man on the Bosporus"

One of the real and deeper causes of the war, however, was the internal disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, which was described by many media of the time as the "sick man of the Bosphorus". Russia saw this as an opportunity to expand its power in Europe and, in particular, to gain access to the Mediterranean and the Balkans. Ottoman rule in the Balkans appeared to be under threat, and Russia was pushing to gain control of the important straits of the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles. Earlier, the Russian Tsar had tried unsuccessfully to persuade the governments of Austria and Britain to partition the Ottoman Empire. Britain and France balked at this Russian expansion. They did not want key positions to fall into Russian hands and supported the Ottomans in order to maintain the status quo and thus secure their own power in southeastern Europe on the Ottoman borders. In the so-called Oriental Question about the continued existence of the Empire, they believed that the Ottoman Empire, which at that time still possessed a vast expanse, stretching from the Balkans to the foot of the Arabian Peninsula, from Mesopotamia in the east to Tunisia in the west, should in principle be preserved. Its collapse would have created a power vacuum. For Great Britain, the Ottoman Empire's most important trading partner at the time, it was also a matter of securing the connecting routes to India and preventing Russian ambitions of supremacy in Asia (The Great Game). Economically, the Ottoman Empire sank to the level of a semi-colonial supplier of raw materials and became increasingly dependent on the economically highly developed countries of Western Europe. British exports to Turkey had increased eightfold between 1825 and 1852. Meanwhile, the empire was the main importer of English industrial products. The Tsarist Empire, on the other hand, had developed into the Ottoman Empire's most dangerous opponent.

An overthrow of the European order created at the Congress of Vienna - which was perceived as disadvantageous - as a result of a congress ending the foreseeable war was Napoleon III's war and peace objective. An opportune moment to apply the lever to the construction of this 1815 order presented itself to Napoleon III in the explosive situation of 1853 in the Orient. His later policy in the Crimean War and especially his attitude after the fall of Sevastopol were strongly connected with the overriding aspect of his great fundamental plan. The Oriental crisis and the fate of the Ottoman Empire interested him only within the limits of their usefulness for the realization of his idea of re-establishing France as a great European power. It was not, however, the only attempt to put his ideas into practice, and for their realization the Crimean War was only a desirable war, but not a necessary one. He hesitated for a long time, considering the risks and sacrifices of war.

In the 19th century, the Oriental question moved onto an international stage. The armed conflict between the strengthened Russian and the weakened Ottoman empire did not automatically mean the entry into the war of the other major European powers, although additional pressure to this end arose from the nationalism that was germinating to varying degrees everywhere. In the wake of the French Revolution, nationalist sentiments were also stirred up in the Balkans among the local peoples of the Ottoman Empire, which became a factor of its own weight in the complex of the question. The aggravation of the question did not alone cause the Crimean War, for the Russo-Turkish War of 1827/28 and that of 1877 did not, like this war, expand into a European one. The role of the element of public opinion present here points to other contributory causes.

Ideologies and enemy images

Russia's motive to crush the Ottoman Empire, however, was not based solely on geopolitical interests. It was also based on the pan-Slavism that had been widespread in parts of Russian society since the beginning of the 19th century and the desire to free the Orthodox Slavic peoples of the Balkans from Ottoman rule. Reports of bloody suppressions of regularly flaring up freedom struggles of the Balkan Slavs outraged the Russian public and led to calls for intervention. Russia saw itself as the protecting power of the Orthodox Christians and claimed to represent both the Orthodox living in its own country and those of the Ottoman Empire. At the same time it was a question of preventing an Islamic and nationalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire.

In Great Britain, France and other countries of Western Europe, on the other hand, there were Russophobic and Turkophile ideas, some of which took hold of larger sections of the population. Russia, for example, was hated by many as the gendarme of Europe, not only oppressing the peoples of Russia but also fighting freedom movements in the rest of Europe. The suppression of the Polish uprising in 1830/1831 and the invasion of Hungary in 1849 were seen as examples.

Some intellectuals, on the other hand, were of the opinion - with regard to the Ottoman Empire - that it could certainly reform itself in a liberal sense. Aggression arose from the many ideological resentments of the West, but these were not directed against Islam in this period, but against Russian Orthodoxy. Clerics and newspapermen in England feared its spread to the Balkans more than they feared the religious domination of the region by Muslims, which had been fought for centuries before. Anglican clergymen in Britain, which at that time liked to regard itself as something like the moral spearhead of humanity, did not hesitate to praise Islam from their pulpits as a beneficial supremacy for Oriental Christianity and to extol its alleged tolerance in contrast to orthodox despotism. Liberal politicians such as Anthony Cooper, the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, for example, appraised the Tanzimat reforms, which were controversial in the Ottoman Empire, as Turkey's dawning of an age of progress and tolerance. The Ottoman-perpetrated massacre of Chios (1822), for example, depicted in a painting by Eugène Delacroix, was omitted. At that time, hundreds of apostates were still executed annually in the Ottoman Empire according to Islamic law. The most modern and technologically advanced empire in the world at the time, Great Britain, went to war against its former Christian ally Russia, alongside a Muslim empire on European soil.

Menshikov's Mission

The trigger for the war was the appearance of Prince Menshikov at the end of February and March 1853. The tsar had sent the military to Constantinople to deliver a series of demands to the Ottoman Empire. Thus, the continuation of the prerogative of Orthodox Christians in the holy places of Christianity and the repair of the dome over the tomb of Christ were demanded, without the participation of the Catholics. The Sultan was at first willing to meet part of these demands. But Menshikov had delivered a second, very far-reaching demand: that the Ottoman Empire recognize by treaty Russia's patronage over the Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire, who constituted one-third of its population. Menshikov's appearance caused the negotiations to break down. It did not help him to extend his ultimatum several times for a few days: the Sultan, supported by the British ambassador, rejected the Russian demands. This gave Russia a pretext for the military escalation of the conflict. Menshikov left on May 21, 1853, amid great éclat. Russia broke off diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire.

Just three weeks later, France and Great Britain sent a clear signal: Their Mediterranean fleets dropped anchor in Besika Bay near the entrance to the Dardanelles. Charles John Napier was appointed commander-in-chief of the British fleet in the Baltic Sea. He sailed his warships into the Baltic as early as March 11, 1854, 17 days before the British declaration of war, to blockade Russian ports. As the Russian fleet then did not engage in combat, Russian shipyards and ports in Finland were attacked or shelled in the following weeks.

The Russian Tsar was then ready to go to war against the Ottoman Empire and its possible allies France and Great Britain. Ivan Fyodorovich Paskevich, the Tsar's most important military advisor, was not sure of Austrian support in such a war, however. He therefore recommended that the Tsar occupy the Danubian principalities, for several years if necessary. This, together with Russian propaganda, would lead to 50,000 Balkan Christians making themselves available to the Tsar as soldiers. This would deter the Western powers from intervening and force Austria into neutrality.

The autocrat Nicholas I, at the military head of the "steamroller Russia", did not strive in a planned manner for the domination of Europe by blowing up the strategically important Dardanelles Lock. The Tsar certainly felt sincerely committed to the rules and norms of conduct as demanded of its participants by the "European concert" embedded in the treaty system of the Congress of Vienna. Against his original will, he was forced into the later war with France and Great Britain.

Kladderadatsch, caricature about the diplomacy of Menshikov, 1853

Prince Menshikov (1787-1869)

.jpg)

Nicholas I (1796-1855)

Lord Palmerston, 1855

Church of the Holy Sepulchre 1864

Military consequences

Changes in the organization and military budgets

After 25 years of Wellington's supreme command, there was a stagnation in the training of the British army; this was evident in the Crimean War. In addition, for example, officers' patents were still sold for money, outdated military tactics were maintained, and they still disciplined their soldiers with corporal punishment. The poor organization of the British army led, among other things, to the overthrow of the Aberdeen government in February 1855. The new Commander-in-Chief of the British Army - Henry Hardinge, 1st Viscount Hardinge - was ordered by Prince Albert to improve the training of the British Army. Thus, the garrison of Aldershot (The Home of the British Army) was established. Aldershot was considered synonymous with the training of the British Army in Victorian Britain.

Overall, the Crimean War led to increased military spending by all states. For the first time, Russia procured cannons with rifled barrels and rifled breech-loading rifles, also from the USA (Remington rifle of 1867). Austria became so indebted for armaments as a result of the Crimean War that austerity programs led to the disbanding of entire units, which was ultimately to contribute to defeats in later wars, among other things.

Strategic consequences

The Black Sea region was to become something like a militarily neutral zone on the basis of the Third Peace of Paris. Henceforth, Russia was not allowed to maintain a navy and fortresses there.

In the two wars only between Russia and the Ottoman Empire, 1828-1829 and 1877-1878, the Russians captured Edirne and marched directly to just outside Constantinople. Again in 1878 there was the prospect of a Russian conquest of the straits; Russia had already conquered practically the entire European part of the Ottoman Empire. The British dispatched their fleet to the Bosphorus and threatened Russia with another war with them. Weakened by the course of the war, Russia could not afford a continuation war against Britain and stopped its offensive at San Stefano (now Yeşilköy, a western suburb of Istanbul on the Sea of Marmara). The Peace of San Stefano ended the tenth and last of the Russo-Turkish Wars.

Technology

In terms of the partly modern technology used, the Crimean War is considered the first "modern" war in world history. For the first time, infantry units were deployed on the British side that consistently used rifles with rifled barrels. This was the Enfield Rifled Musket, a Miniégewehr-type muzzle-loader with a 99 cm barrel length in 0.577 inch (.577) or 14.66 mm calibre, which had been introduced in 1852 and had an effective range of 800 metres, in massed fire up to 1000 metres. On the Russian side, by contrast, smoothbore muskets were still in use, with an effective range of about 200 yards. The success of the British Enfield rifle led to Prussia and all other great and middle powers equipping their entire infantry with rifled rifles, which had previously been reserved for the so-called fighter troops. The effect of this rifle was so impressive to the military that shortly after the war - soon to become obsolete - they began to consider dispensing with artillery altogether.

However, the British military in general was still stuck in the ideas of the Napoleonic Wars and the British soldiers received the new long-range Minié rifles (the last muzzle-loaders of this type of rifle) only shortly before their departure for the Crimea; very few soldiers had undergone training on them. This was revealed at the Battle of the Alma. The infantry, having already decimated themselves in several senseless bayonet charges, opened fire on the advancing enemy at an unusually long range, contrary to the orders of their overtaxed officers. They thus brought the surprised Russian columns to a standstill in many cases.

The new weapons technologies led to social upheavals in the military. Longer-range, more precise and more energetic rifles and artillery made traditional officers and generals in splendid uniforms on horseback or decoratively on commanders' mounds pale into insignificance. Meanwhile, the higher social classes were just as much in the dirt with the "common soldier" or hiding in bullet-proof dugouts. As before, war was located on land and sea, but soldiers and technology increasingly moved underground. This war was also moved under the water surface, especially in the Baltic Sea area, with naval mines from the Russian side. Explosive power and technology were still in the early stages of development, but electromagnetic remote detonation of underwater mines was already available. An air war had not yet been fought. Until World War I, most military leaders did not realize what could have been done with the tactical battlefield reconnaissance technology already available using reconnaissance balloons. The first air attack by means of balloons on a city (Venice) took place already in the revolution years 1848/49 by Austrian troops under field marshal Radetzky. In the classic war of movement, there was little use for such cumbersome equipment anyway. It was only in the course of the World War that the advantages for positional and trench warfare were fully recognized and realized. This was mainly due to the lack of coordination and the limited expertise of the higher command authorities or army agencies.

In the more than eleven months of the Sevastopol siege, 120 kilometers of trenches were dug by all warring parties. About 150 million rifle shots and 50 million gun shots were fired. However, the real technical revolution of firearms was still to come, so that the Crimean War still enjoyed a high level of public acceptance and the image of the war of bygone days, which was widely glorified among the population, could still be maintained. On the one hand, technical innovations were already being used militarily; on the other, this war was still partly characterized by colorful troop collisions, for example. Contemporary paintings, mostly without much documentary accuracy, give us a good idea of the sometimes spectacular and colourful appearance of the war. There is evidence in pictures of commanders who still directed their armies from the proverbial commander's hill by visual contact in the field battle and staged a colourful martial spectacle in the advance of their regiments - by now completely inexpedient from a military tactical point of view. Despite all the mass deaths, this war was probably the last time that there were any comprehensive echoes of traditional soldierly virtues, such as chivalry. Parliamentarians with white flags, for example, still regulated truces and evacuations of the wounded and fallen on the battlefields on a large scale. Steam warships armoured with cast-iron plates were used for the first time, and the French and British navies developed them into so-called ironclads after the war. Steam propulsion allowed greater speed and independence from the wind. Also new was modern artillery with explosive shells. During the siege of Sevastopol the British had their base in the harbour town of Balaklava. They therefore built the first strategic railway line in the history of railways here in 1855 to transport their supplies from Balaklava to the camp of the British-French siege army outside Sevastopol. Under Thomas Brassey's direction, work began in September 1854 on the eleven-kilometre stretch of the Great Crimean Central Railway. It was completed after only seven weeks and before the onset of winter.

The Crimean War was also historically the first trench and positional warfare. Furthermore, the Crimean War with the death ride of Balaklava challenged the use of the classical cavalry charge, as it was hardly able to prevail against the more modern faster, more energetic, respectively more accurate firing weapons in connection with the changing field entrenchments. The cavalry, however, retained an important function until the later emergence of extensive motorization of armies.

The electromagnetic telegraph was used for the first time on a large-scale strategic and tactical scale. On the Russian side, several optical-mechanical telegraph lines based on the Chappe system already existed before the war. In addition to the Moscow - St. Petersburg - Warsaw line, there was also a connection from Moscow to Sevastopol in the Crimea, which allowed a simple message to be transmitted in about two days. In 1854, Russia began building much faster electromagnetic telegraph lines from Moscow again to St. Petersburg and Warsaw and south to Odessa and Sevastopol, which were completed in 1855. These lines allowed Russia to coordinate troop and materiel movements, as well as establish rapid contact with Berlin for ordering war supplies.

On the Allied side, the existing electromagnetic telegraph network from London via Paris to Bucharest was extended to Varna on the Black Sea. In April 1855, the longest submarine cable to date, 550 kilometres long and made of iron wire insulated with gutta-percha, was laid from Varna to Balaklava in the Crimea in just 18 days. This reduced the time for a message from Paris to the Crimea from previously twelve days to three weeks to only 24 hours. Field telegraphs were first used in the Crimea by the French and British, the cables being laid by means of a wagon with a plough or by digging trenches in the ground. Submarine cables as well as field telegraphs proved short-lived, however; the lines of the field telegraphs often broke, and the submarine cable also broke in December 1855, shortly after the fall of Sevastopol, without being repaired. Little research has been done on the importance of the then new means of communication for the course of the war, but two aspects on the Allied side are highlighted: First, news from the front reached the public in France and Britain within a very short time, drawing warfare into the arena of politics. Second, the chain of command extended to headquarters in Paris and London.

This was seen as ambivalent progress by commanders in the field. They believed that the efficiency of warfare suffered because tactical decisions, which until then had been made on the ground, were interfered with by heads of state far removed from the theatre of war. British General Simpson is reported to have said, "Telegraphy has made a mess of everything!" French General Canrobert resigned his command in part because of Napoleon III's telegraphic interference in the conduct of the Crimean campaign.

For all the influence that new technological developments had on the war, Britain, of all countries, the most modern and technologically advanced country in the world at the time, failed to meet the tactical and logistical demands of this first war of the modern era.

In 1989, the historian and journalist German Werth described the Crimean War as an "anticipation of Verdun". From now on, human lives mattered less than ever, and only a few years after the Crimean event, 200,000 soldiers fell in the American Civil War, 400,000 succumbed to their wounds, illnesses and privations.

The aftermath of the cannon bombardment of buildings.

Routes of the Strategic Railway

The cramped starting point of the strategic railway line in the port of Balaklava

.jpg)

Port of Balaklava in 1855: sailing and steamship technology side by side. Above all, the armoured steamships of the French fleet were technically far ahead of the Russian navy. The Tsarist Empire could not keep up with the industrialization of England and France.

Questions and Answers

Q: Who fought in the Crimean War?

A: The Russian Empire fought against the French Empire, the United Kingdom, the Kingdom of Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire.

Q: Where did most of the fighting of the Crimean War occur?

A: Most of the fighting, including the Battle of Balaclava, occurred in Crimea, but some of it took place in what is now western Turkey and around the Baltic Sea.

Q: What is the Crimean War sometimes called, and why?

A: The Crimean War is sometimes called the first "modern" war because its weaponry and tactics were used for the first time and affected all later wars.

Q: What was the significance of the Crimean War?

A: The Crimean War was significant in that it was the first war to use a telegraph to give information to a newspaper quickly.

Q: When did the Crimean War take place?

A: The Crimean War took place from 1853 to 1856.

Q: Who won the Crimean War?

A: The war ended in a stalemate, but the Russian Empire was defeated, and its power and influence were significantly weakened as a result.

Q: What was the main location of the battles in the Crimean War?

A: Most of the fighting took place in Crimea, a peninsula in the Black Sea region of Eastern Europe.

Search within the encyclopedia