Crime and Punishment

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Guilt and atonement (disambiguation).

![]()

Crime and Punishment is a redirect to this article. For the film of the same name, see Crime and Punishment (film).

Crime and Punishment (Russian Преступление и наказание Prestuplenije i nakasanije), also Raskolnikov in older translations, Crime and Punishment in more recent ones, is the first major novel by Fyodor Dostoevsky, published in 1866. The novel was published, while Dostoevsky was continually writing more chapters, as a feature novel in 12 installments in the monthly Russki Westnik, beginning in late January 1866 and ending in December 1866.

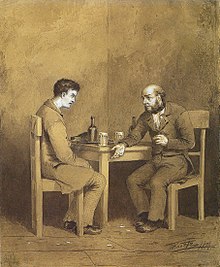

Raskolnikov and Marmeladov . Illustration by Mikhail Petrovich Klodt, 1874. .

Title

The original Russian title of the novel, Prestuplenije i nakasanie (Преступление и наказание), cannot be translated exactly into German. However, the most common translation title Schuld und Sühne (guilt and atonement), with its strong moral orientation, does not match the Russian terms, which are more likely to come from legal usage. A more accurate translation is Verbrechen und Strafe (Crime and Punishment), which again does not fully capture the ethical content of the Russian terms. This title was used after Alexander Eliasberg in 1921, among others by Svetlana Geier in her much acclaimed new translation of 1994; Geier mentions the words Übertretretung and Zurechtweisung as possible alternatives. In other languages such as English, French, Spanish and Polish, on the other hand, the title Verbrechen und Strafe has always been preferred (Crime and punishment, Crime et châtiment, Crimen y castigo and Zbrodnia i kara respectively). In Romanian, the title Murder and Punishment (Crimă şi pedeapsă) was used. The novel was also partially published in German under the name of its main character, Rodion Raskolnikov.

Storyline

Main storyline

The novel is set in St Petersburg around 1860 and features Rodion Romanovich Raskolnikov, a bitterly poor but exceptionally gifted former law student. The mixture of poverty and conceit of superiority increasingly splits him off from society. Under the impression of an inn conversation he overhears, he develops the idea of "permitted murder", which seems to support his theory of "the 'exceptional' people who enjoy natural privileges in the sense of general-human progress". He sees himself as such a privileged person who knows how to maintain calm and overview even in the situation of a "permitted crime".

This self-claim is countered by the oppressive, cramped external circumstances. Raskolnikov's clothes are ragged, and he lives in a room of coffin-like confinement. His precarious financial situation forces him to turn to that old usurious pawnbroker, Alyona Ivanovna, to whom his murder plan has long been directed. To him, she is nothing but a stingy and heartless old woman who lives solely to amass an ever-increasing fortune to be used for her salvation - the fortune is to go to the church after her death. For Raskolnikov, she is the epitome of a "louse", a worthless person whose life the truly great people are allowed to pass over.

Inherited in this worldview, the idea of murdering the pawnbroker becomes more and more entrenched in Raskolnikov until, prompted by a letter from his mother about his sister's unjust fate, he finally comes to the obsessive decision to take action. Later, he conceals his inner resistance, which accompanies him throughout the execution, by ideological motives. Thus he tells Sofja Semjonowna Marmeladowa, called Sonja, a young girl who prostitutes herself because of her family's need for money: "I wanted to learn then, to learn as soon as possible, whether I was a louse, like everyone else, or a human being." "A man" here means for him: a great man, a Napoleon, whom he cites as an example of such "permitted" ruthlessness.

He visits the old woman under a pretext and kills her with a hatchet. He splits the skull of her accidentally appearing sister Lisaveta, a mentally retarded person symbolizing innocence, with the axe. Only with great luck can he escape undetected. His nervous tension also does not allow him to seize the old woman's money. He is not up to his own standards, as he must discover. Thus, after the deed is done, he falls into a feverish stupor lasting several days; he is not the man without conscience that he thought he was. Moreover, the act of murder has changed him: Although Raskolnikov has remained undetected with his crime, as a double murderer he now feels the social segregation inwardly all the more painful.

After the murder he can no longer find peace, he even rejects his own mother. So it is not long before he is recognized as the guilty party by the investigating judge Porfirij, although he is unable to prove Raskolnikov's culpability. Both the perpetrator and the investigator are aware of this, even if it is not openly expressed. Instead, the intellectual battle between the adversaries escalates into a subtle psychological game, which, although Raskolnikov could be reassured by the outward state of the investigation, drives him more and more into a corner. The devout Sofya Semyonovna, whom he meets and later comes to love, finally advises him to turn himself in to "pay" for his sins. Raskolnikov, who has himself considered and rejected going to the police several times, does indeed turn himself in.

In the epilogue, Raskolnikov's eight years of imprisonment in a Siberian labour camp are sketched out as an almost physiological, protracted liberation from the past in Petersburg based on the intense experience of the time. At the end of the novel, he discovers his love for Sofja (who travelled with him), which is accompanied in the narrative by metaphors of resurrection. However, the novel does not give a clear answer to the much-discussed question of whether Raskolnikov finds Christian faith at the end. In the last paragraph, a possible continuation of the story is hinted at, but Dostoevsky never wrote it.

Subplots

More closely than in other novels by Dostoevsky, the main and subplots are related to each other both personally and thematically. Thus, the author has included various parallel or contrasting plots related to Avdotya and Sonya, which complement the guilt and atonement theme:

Sofja (Sonja) feeds her family through prostitution because her father Semjon Sacharowitsch Marmeladow, as an alcoholic, does not fulfil his duties, loses his jobs several times, pawns all his valuables and even his uniform, disappoints his second wife Katerina and their children Polja, Kolja and Lida again and again through his unkept promises, is finally run over by a carriage while drunk and dies of his injuries. Raskolnikov sees here a paradigmatically desolate situation of the poor people.

While Raskolnikov receives new courage to live through Sonja's love, his sister Awdotja (Dunja) cannot play this redeeming role with the landowner Arkadij Iwanowitsch Swidrigailow. During her employment as a governess, she has been courted by the landlord, who is in love with her and has hoped for her to save him from his sinful life, especially his pedophilic or parthenophilic tendencies. In his nightmares, the 14-year-old girl he abused appears to him, drowning herself after the act because of the shame she suffered (Part 6, Chapter 6). As atonement, he tries to compensate his inclination with financial benefits. Thus, after, as it is colocated, poisoning his wife Marfa, he becomes engaged to a 15-year-old girl who fascinates him with her Madonna face, after receiving the richly paid blessing of her parents (6/4). He also supports Sonja after the death of Marmeladov and his wife Katerina, driven mad by her misfortune, and pays for the children's placement in an orphanage. He seeks to win Avdotya's affection by sharing with her the truth about Rodion's crimes, learned through an overheard conversation he had with Sonja, and by offering to help him escape abroad if she will become his wife. She refuses his proposal (6/5) because she loves Rodion's friend Dmitri Razumikhin, and he shoots himself in his hopelessness (6/6). Raskolnikov seeks a similar way out before his confession when he crosses a Neva bridge, but he cannot bring himself to commit suicide and follows Sofia's advice (6/7).

Sofja and Dunja are connected not only through Rodion, but through a second person: the advocate Pyotr Petrovich Lushin, through Marfa Svidrigailova's mediation - she thus wants to accommodate a rival in a marriage - becomes engaged to Dunja, who, as a poor girl, will be dependent on him and whose gratitude he expects as the basis of his marriage. When she breaks up with him, partly on the advice of her brother-in-law-to-be, he wants to prove to her her brother's moral depravity, since he, despite his own financial problems, helps Sofja's uprooted family and adores their socially ostracized daughter for her sacrifice for her relatives. Lushin lures Sofja into a trap and accuses her of theft. However, his plot fails due to the testimony of the witness Andrei Lebesyätnikov (5/3). Raskolnikov, who is present at this unmasking, sees himself vindicated in his criticism of an immoral, unjust society from which he wants his deed to be distinguished and which is therefore not entitled to judge him. Such experiences are a major reason why the protagonist refuses to face justice for a long time.

Questions and Answers

Q: Who is the author of the novel "Crime and Punishment"?

A: Fyodor Dostoevsky is the author of the novel "Crime and Punishment".

Q: When was "Crime and Punishment" published?

A: "Crime and Punishment" was first published in the literary journal The Russian Messenger in 12 monthly series in 1866.

Q: Was "Crime and Punishment" published as a single volume later on?

A: Yes, "Crime and Punishment" was later published in a single volume.

Q: How would you describe "Crime and Punishment" in terms of its significance in the author's works?

A: "Crime and Punishment" is the second of Dostoevsky's novels, written after he returned from his punishment (exile in Siberia). It was the first great novel of his mature period.

Q: In what language was "Crime and Punishment" originally written?

A: "Crime and Punishment" was originally written in Russian.

Q: What was the format of the original publication of "Crime and Punishment"?

A: The original publication of "Crime and Punishment" was in 12 monthly series in a literary journal.

Q: What is the genre of "Crime and Punishment"?

A: "Crime and Punishment" is a novel.

Search within the encyclopedia