Alexander von Humboldt

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Alexander von Humboldt (disambiguation).

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt (* 14 September 1769 in Berlin; † 6 May 1859 ibid.) was a German explorer with a sphere of influence that extended far beyond Europe. In his complete works, written over a period of more than seven decades, he created "a new state of knowledge and reflection of the knowledge of the world" and became the co-founder of geography as an empirical science. He was the younger brother of Wilhelm von Humboldt.

Several years of research trips took Alexander von Humboldt to Latin America, the USA and Central Asia. He conducted scientific field studies in the fields of physics, geology, mineralogy, botany, vegetation geography, zoology, climatology, oceanography and astronomy, among others. Further research concerned economic geography, ethnology, demography, physiology and chemistry. Alexander von Humboldt corresponded with numerous experts from various disciplines and thus created a scientific network of his own.

In Germany, Alexander von Humboldt achieved extraordinary popularity, especially with his works Views of Nature and Cosmos. Even during his lifetime he enjoyed a high reputation at home and abroad and was considered "the greatest naturalist [of his] time". The Academy of Sciences in Berlin praised him as "the first scientific greatness of his age", whose world fame surpassed even that of Leibniz. The Paris Academy of Sciences gave him the epithet "the new Aristotle".

The complexity of Humboldt's work and life meant that, after his death, numerous social and political movements invoked him for their respective goals. Since the end of the 20th century - under the impression of a comprehensive globalisation - his work has been received as a pioneer of ecological thinking, for whom the insight applied: "Everything is interaction".

Reception aspects

In the 21st century, Alexander von Humboldt has become "a highly significant figure in public discourse" in the most diverse "fields of knowledge and science" as well as among a broad public, according to Ottmar Ette. In many other countries, Humboldt has been "continuously present" in the general consciousness, but in the German-speaking world it has taken a variety of efforts "to regain awareness of the buried traditions of his research and his designs for science and economics, culture and conviviality.

Among contemporaries

Wilhelm von Humboldt made his brother Alexander appear to his wife Caroline as the antithesis of himself in his orientation "outwards". Alexander likes to show what he can do and what he knows. "Only in order to gain a large sphere of activity, he does many things that must seem necessary vanity to others, digs out his knowledge, seeks to dazzle people with it, soon to win them over. If I myself had so much knowledge, I would never show it in this way; I would always be more anxious to have it trained myself than to apply it directly to others."

Among the Weimar classics, it was originally Friedrich Schiller to whom Alexander von Humboldt felt more attracted than to Goethe. But Schiller had little understanding for the ambitions of the younger of the Humboldt brothers: "I do not yet have a correct judgement of Alexander; I fear, however, that despite all his talents and his restless activity, he will never achieve anything great in his science. [...] It is the naked, cutting intellect that shamelessly wants to measure nature, which is always incomprehensible and in all its points venerable and unfathomable, and with an impudence that I do not understand, makes its formulas, which are often only empty formulas and always only narrow concepts, its standard. In short, it seems to me that he is far too crude an organ for his subject, and at the same time far too limited an intellect."

The contacts between Alexander von Humboldt and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe extended over three and a half decades in a loose sequence and varying intensity in a relationship determined by the highest mutual respect. In 1795 Goethe and Alexander von Humboldt worked together on the first draft of a general introduction to comparative anatomy, based on osteology. Goethe's questions about the archetype and wholeness exerted the strongest influence on Humboldt; however, Goethe noted a striking difference in their methodological approaches: while he himself proceeded from the figure and the whole, for Humboldt it was the element and the part, respectively. Differences of opinion between the two arose not only with regard to volcanism - for Goethe the "vermaledeite Rumpelkammer der neuen Weltschöpfung" - but also with regard to Goethe's theory of colours, which Humboldt rejected. Notwithstanding such differences, which were not settled publicly, Goethe described Alexander von Humboldt to Eckermann as a "fountain with many pipes, where one only needs to keep vessels underneath everywhere and where it always flows towards us refreshingly and inexhaustibly."

Among the personalities influenced by Humboldt was Charles Darwin, who also studied Humboldt's travelogue from the tropics in preparation for his Beagle expedition. A great similarity has been noted in Darwin's travel diaries, both in the way they view nature and in the way they are executed in writing. The view of Humboldt by Emil du Bois-Reymond as a "pre-Darwinian Darwinian" has been contradicted in more recent times, for statements on the problem of the origin and transformation of species, which had been frequently discussed even before Darwin, were considered by Humboldt, who was oriented towards empirical methods of natural research, to be speculative and inadmissible, and he denied himself them.

On 1 July 1859, the Academy of Sciences in Berlin commemorated Alexander von Humboldt - who had forbidden his bust to be erected next to that of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in the Academy during his lifetime. The philologist and historian August Böckh gave the commemorative address, which included the following statement: "A brilliant star in the realm of the spirit has gone out for this world. [...] undisputedly he remains in general recognition the first scientific greatness of his age. [...] By placing his bust now near Leibniz's, we honor more ourselves than him, who deserves not a bust in this gloomily vaulted hall, but a statue under the open firmament of the divine cosmos beside the benefactors of the fatherland." The naturalist Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg also emphasized that "a new epoch of earth and world view" had begun with Humboldt's writings. Ten years later, Rudolf Virchow and other prominent figures campaigned for the erection of a national monument to Alexander von Humboldt. It was not until 1874 that Wilhelm I allowed a monument to be built for the Humboldt brothers at the entrance to the university grounds, but with the proviso that the figures could under no circumstances be as high as the nearby statues of Generals Bülow and Scharnhorst. The dedication of the two Humboldt monuments took place on 28 May 1883.

Abroad, too, Humboldt's life's work was exceptionally honoured in many places. In Paris, Humboldt's place of work for many years, he was regarded by his fellow researcher Claude-Louis Berthollet, with whom he met in the Société d'Arcueil, as a man who united "an entire academy" in himself. The Paris Academy of Sciences had a commemorative coin minted for him after Humboldt's passing, "the greatest scholar of his century" with the epithet "The New Aristotle". Simón Bolívar called him the real "discoverer of the New World" who had given America better things "than all the conquistadors." In Mexico, President Benito Juárez declared Humboldt a "benefactor of the fatherland" in a decree of 28 June 1859 and suggested the erection of a marble monument to him.

The centenary of Alexander von Humboldt's birth - a good ten years after his death - was celebrated internationally with enthusiasm and great expense. From Melbourne and Adelaide, to Moscow and Alexandria, to Buenos Aires and Mexico City, the celebrations stretched - with the largest events in the United States. "From San Francisco to Philadelphia and from Chicago to Charleston, there were street parades, feasts and concerts." In New York, thousands followed the marching bands in tribute to a man of whom the New York Times wrote that no nation could claim his fame. The largest German celebration occurred in Humboldt's hometown of Berlin, where "despite torrential downpours, eighty thousand people gathered. All offices and authorities remained closed that day."

However, the appreciation and reception of Alexander von Humboldt in Germany was already partly limited and partly distorted during his lifetime and thus to this day. In addition to the long-standing "hereditary enmity" between the Germans and the French, popular editions of Humboldt's writings contributed to this, which were edited by the respective compilers very freely and sometimes in a way that was contrary to their meaning. The various recent editions of Alexander von Humboldt's original writings can, however, serve, among other things, to counteract a misguided reception.

Recent and current

Humboldt was first described as the "first ecologist" by Pierre Bertaux in 1985. Matthias Glaubrecht opposes an uncritical glorification of Alexander von Humboldt. For example, Humboldt did not adequately acknowledge Jean-Louis Giraud-Soulavie as an important forerunner of his own plant geography research and rather marginalized the animal geography approach of Eberhard August Wilhelm von Zimmermann, which is why he did not find access to Darwin's theory of evolution. For Glaubrecht, the "cosmic approach" of Humboldt's understanding of nature was already unsustainable and his world view "long outdated".

Benedikt Vallendar, who has examined the reception of Humboldt's American voyage of discovery in Germany against the background of the respective intellectual currents and political framework conditions in the 19th and 20th centuries from a socio-psychological point of view, summed up that it was not "gaining knowledge" but the urge to interpret and instrumentalisation that had frequently been the driving forces in the history of reception: "The combination of scientific documentation and narrative style was a suitable vehicle for many authors to appropriate Humboldt for their own purposes." During the 19th century, according to Vallendar, the reception of Humboldt's travelogues in Germany was predominantly determined by a dismissive to hostile mood towards France. In the era of the Kaiserreich, there were voices that appropriated Humboldt as a "proud German" despite his long stays abroad. At the beginning of the Weimar Republic, on the other hand, the cosmopolitan-oriented Humboldt, because of his advocacy of humanity and progress and because of his critical distance from dictatorial regimes, had become "a role model for the public humiliated by the lost war," "which sought to come to terms with the burdens of the past." During the National Socialist era, Humboldt was portrayed, among other things, as a "fighter" who held his own in the jungle struggle for survival and as a "trailblazer into the world as a whole."

The two world wars of the 20th century greatly dampened Humboldt enthusiasm, especially among Germany's wartime opponents, beginning with the United States' entry into the war in 1917. In Cincinnati, for example, all German publications were removed from the shelves of public libraries and "Humboldt Street" was renamed "Taft Street". During the period of German bi-statehood from 1949 to 1989, there were different interpretative interests and claims on both sides.

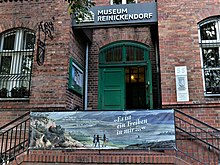

To mark the 250th anniversary of Alexander von Humboldt's birth in 2019, numerous thematic events took place in the Berlin district of Reinickendorf. The venues included the Humboldt Library adjacent to Tegel Palace and the Museum Reinickendorf. A cultural institution that follows on from Alexander von Humboldt's ideas is the Humboldt Forum in the museum centre of the capital of reunited Germany, which, contrary to plans for 2019, is not yet finished. According to Rüdiger Schaper, Alexander von Humboldt had already envisaged a universal museum for Berlin's collections in 1807 - incorporating the Kunstkammer of the palace whose reconstructed parts now provide the setting for the Humboldt Forum - but it never came to pass. "The Humboldt Forum now wants to pursue this connection between nature and culture with a delay of more than two hundred years." "The claim to present world knowledge in the spirit of Humboldt, to abolish the separation between nature and culture in the process, and to understand the world as a whole on the basis of Berlin's rich collections, is a broad goal and leaves plenty of room for different interpretations."

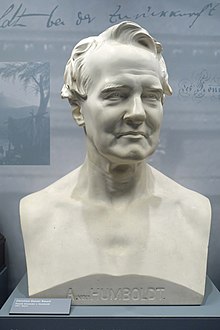

Alexander von Humboldt (Bust by Christian Daniel Rauch, 1857)

Anniversary exhibition at the Museum Reinickendorf on the occasion of Alexander von Humboldt's 250th birthday

Honors

Membership in scholarly associations

Alexander von Humboldt was a member of numerous domestic and foreign academies, including the Akademie gemeinnütziger Wissenschaften zu Erfurt (1791), the Leopoldinisch-Karolinische Akademie der Naturforscher (1793 with the academic epithet Timaeus Locrensis under matriculation no. 970), the Prussian Academy of Sciences (1800), the Bavarian Academy of Sciences (1808), the Royal Society of Edinburgh, the Academy of Arts (Berlin) (1829), the Russian Academy of Sciences (1829), the Académie des sciences (1804), the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1822), the American Philosophical Society (1804), and the Société cuvierienne (1838).

Honorary doctorate

Alexander von Humboldt was an honorary doctor of the universities of Frankfurt (Oder) (1805), Dorpat (1827), Bonn (1828), Tübingen (1845), Prague (1848) and St. Andrews (1853).

Awards during lifetime

Alexander von Humboldt was awarded these orders and decorations:

- Order of the Red Eagle (Prussia, in various degrees)

- Order of the Black Eagle (Prussia)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Bavarian Crown

- Grand Cross of the Brazilian Order of the Rose

- Grand Cross of the Danish Order of Dannebrog

- Grand Cross of the French Legion of Honour

- Grand Cross of the Mexican Order of Guadeloupe

- Grand Cross of the Portuguese Order of Christ

- Russian Order of Alexander Nevsky and Order of St. Vladimir

- Grand Cross of the Order of Saxony for Civilian Services

- Grand Cross of the Weimar House Order of the White Falcon

- Grand Cross of the Sardinian Order of Knights of St. Maurice and Lazarus

- Grand Cross of the Spanish Order of Charles III.

Statues and monuments

- Monument in honour of Alexander von Humboldt designed by Gustav Blaeser, built in 1869 for Central Park in New York by Georg Ferdinand Howaldt.

- Monument in honour of Alexander von Humboldt in Philadelphia, after design by Johann Friedrich Drake, 1876

- Monument in honor of Alexander von Humboldt in St. Louis, after design by Ferdinand Miller, 1878

- Seated picture in front of the main building of the Humboldt University in Berlin, executed by Reinhold Begas from 1882 to 1883.

- Monument in Humboldt Park in Chicago, created in 1892 by Felix Göring

- Secondary bust to the central statue of Frederick William IV in monument group 31 of the Siegesallee, executed by Karl Begas in 1900.

Stamps, banknotes, coins and medals

·

40-Pf special stamp of the Deutsche Bundespost Berlin (1957) from the series Men from the history of Berlin

·

40-Pf special stamp of the German Federal Post (1959) for the 100th anniversary of his death

·

5-Pf special stamp of the German Democratic Republic (1950)

· _1959,_MiNr_0685.jpg)

20-Pf special stamp of the German Democratic Republic (1959)

·

50-Pf special stamp of the German Federal Post Berlin (1969) for the 200th birthday

·

5-Mark banknote of the Deutsche Notenbank (1964-1967)

With a first day of issue of 5 September 2019, Deutsche Post AG issued a special postage stamp with a face value of 80 euro cents on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Finance to mark the 250th anniversary of Alexander von Humboldt's birth. The design was by graphic artists Horst F. and Gerda M. Neumann from Wuppertal. A commemorative 20-euro coin appeared on the same day; the edge of the coin bears the embossed inscription "ALLES IST WECHSELWIRKUNG".

·

Medal Alexander v. Humboldt (Loos 1829), 41 mm, ca. 46 g

·

Medal (Loos 1829), reverse side

Humboldt as name donor

→ Main article: List Humboldt as name donor

Numerous biological taxa have been named after Alexander von Humboldt, as well as geographical objects, places, schools and institutions, scientific awards and more. In 1969, it was determined that no other person has had more places named after him. The number of namings has now reached four digits.

Commemorative plaque commemorating Humboldt's honorary membership of the Danzig Natural History Society near the banks of the Motlawa River in Gdansk

Bronze bust of Alexander von Humboldt on the campus of the University of Havana. The original was created by the Erfurt theatre sculptor Christian Paschold. He donated a copy of this bust to the mining museum of the "Morassina" show mine in Schmiedefeld (Saalfeld-Rudolstadt district).

Questions and Answers

Q: Who was Alexander von Humboldt?

A: Alexander von Humboldt was a Prussian naturalist and explorer.

Q: What was Humboldt's area of expertise?

A: Humboldt's area of expertise was in botanical geography.

Q: What was the significance of Humboldt's work?

A: Humboldt's work was very important in the field of biogeography.

Q: When was Alexander von Humboldt born?

A: Alexander von Humboldt was born on September 14th, 1769.

Q: Where was Humboldt born?

A: Humboldt was born in Berlin, Prussia.

Q: When did Alexander von Humboldt die?

A: Alexander von Humboldt died on May 6th, 1859 in Berlin.

Q: What was Humboldt's main contribution to the field of natural science?

A: Humboldt's main contribution to the field of natural science was his work on botanical geography, which was important to the field of biogeography.

Search within the encyclopedia