Cosmogony

Cosmogony (Greek κοσμογονία kosmogonía "world generation"; in older texts also cosmogeny) refers to ideas about the origin and development of the world or cosmos: ancient Greek for (sparkling) jewel. They either present the creation of the world in a mythical way or undertake attempts to explain this process rationally. Cosmogonic myths are usually of ancient origin (still alive among some peoples), cosmogonic theories, on the other hand, are the results of philosophy and those natural sciences that were determined by it to investigate this subject.

Cosmogony and cosmology are not clearly delimited terms; they are used in scientific as well as in philosophical and mythical contexts. However, "cosmology" is mainly understood as that natural science which deals with the present structure of the universe by means of physics and astronomy, whereas cosmogony as a sub-discipline deals specifically with its beginning from an energetic singularity and the further development of the spatio-temporal structure up to its standstill or return to a singularity. (Big bang, steady-state and all-pulsation theories).

Cosmogonic myths go hand in hand with the unexplicit claim to make the origin of the world comprehensively imaginable, to create "meaning" and thus to establish a basic order for man in his earthly habitat. Where myths are part of cultural identity, they can have a similarly strong persuasive power as science.

The philosophical cosmology of the Greek pre-Socratics began speculatively with reference to much older mythical ideas; for example, there is a clear connection between Thales' water-world theory and the Sumerian Apsu. The pre-Socratics Parmenides surprised us with his modern theory of a cosmos that had its beginning in an entity and would end there. He developed this assumption by way of highly rational thinking about the nature of truth, as well as its deviation: the only "probable". At a distance of almost 100 years this led to the development of Plato's doctrine of ideas.

At the beginning of the modern era, it was René Descartes who for the first time designed a model of the origin of the world on the basis of a rationalistic metaphysics. Its common ground with Plato's doctrine is the assumption of presuppositionless given forms of judgement (categories of cognition): neither 'synthetically' further explainable nor 'analytically' further decomposable noumenal units ('ideas'), on the basis of which our mind judges and thereby sorts the sensory stimuli it receives. This process runs unconsciously and produces complex ideas like a rose or the all of phenomena by means of 'synthetic' assembling of the stimuli, both during sleep - in the form of symbolic actions of our dreams - , and in waking. This is necessary in order to respond meaningfully, i.e. according to a set of natural needs, to the sources of stimuli. Be it in communication, be it in motor cooperation, theory or practice (pure looking and doing). Man is a being who, like the cosmos, lawfully originates from an entity that remains incomprehensible and evolved from the dust of exploded suns, so Darwin's theory is not sufficient to explain in a well-founded way what we are and what we should, actually want. Cosmology is also the study of the evolution of inanimate matter, since eons before the beginning of the evolution of living molecules on planets suitable for them.

This article is mainly about mythology. Religious myths of the origin of the world is also discussed in the article Creation.

Distinctions

The starting point is the same: the origin of the world lies far from any possibility of observation at the beginning of time in the past and is not repeatable in experiment. The big bang theory is generally accepted in science, but the singularity from which the cosmos began, according to this theory, is not in itself empirically detectable. Scientific assumptions and methods begin to fail beyond a certain limit. In this respect, the singularity that still lies beyond this limit represents a purely logical conclusion. It is merely calculated from Einstein's gravittaion theory, not factually established. Only the statements referring to this singularity can be tested. If phenomena can be explained on the basis of such a hypothesis, or predictions can be made which come true, it is considered to be true and changes to the status of a theory. If the empirical (measurement) findings deviate, the hypothesis is adjusted or is considered to be refuted.

All cultures of mankind are in possession of mythical narratives that have been passed down from one generation to the next since time immemorial. They have changed over the course of thousands of years, with the oldest accounts being joined by newer ones, each marking a particular event, so the myths of humanity deal with a succession of different ages. Levi Strauss found that every culture in the world passes on a catalogue of myths, which is always divided into six sections, the so-called mythemes. The first mytheme is always considered to be the epitome of happiness on earth, but in the second it is shaken by a political conflict (upper, heavenly gods come into conflict with lower, earthly gods) and gradually lost completely.

This first mythem always tells, albeit in different ways, of the beginning of the world - arising from a monistic entity like a river or world tree - and thus that of the culture whose thinkers and poets conceived the respective idea. Their narration impressed the listeners - which is why they passed it on to their descendants. Whether consciously or unconsciously, cosmogonic myths breathe "meaning" into the world by relating all subsequent experience to the "beginning of everything". In doing so, the myth describes a reality that was sufficient for the authors and their audience as an explanation of world events (subjective truth).

The difference to a philosophical-scientific cosmogony is that the creation myths do not mainly strive for or offer rational insight into the interrelationships, but rather have the life-giving aspect of their ideas of the beginning of the world as their central object, be it a great river, a mighty tree bearing fruit, or the rainbow serpent of the primitive peoples of Australia, still invisibly uniting heaven and earth within itself, which, upon awakening from sleep, began to move and create the world.

The primeval myths of mankind are purely "animistic" (anthropomorphization of the male sky and the female earth by means of projected human characteristics such as overview and childbearing capacity) and thus different in nature from the "religious" cosmogonies. The latter take over parts of the uranimistic narratives - the Mosaic Genesis, for example, the saluppu tree of life and the cosmic freshwater ocean of the Sumerians - but they threaten people with punishments in case of violations of special rules of conduct and demand - as a religious virtue - surrender. Man is supposed to submit to the omnipotence of the highest of the 'good' gods and the 'evil' demons (who dwell underground) serving as his instrument of revenge, not ask why. Suffering' has an absurd meaning (that of punishment for original sin, for example); 'redemption' is postponed to the hereafter after death.

Cosmogony as a science

The laws of nature discovered by science itself form the outermost framework of empirically based knowledge. With the Planck scale, a limit for physical quantities was defined, below which attempts to calculate the location and dynamics of a phenomenon fail for reasons of principle, and already slightly above which measurements are practically no longer possible. The explanation offered by contemporary science for the first cause of the universe: a singularity of pure energy located 'before' the beginning of space and time - thus seems to be paradoxical or mere speculation. Metaphysically, however, that is, according to epistemology, our dimensional-temporal thought processes must emanate from and flow back into an undimensional-noumenal source, must have an initial endpoint that cannot in turn be imagined. Logic cannot itself be logically explained; the causal nexus of our imaginative universe is rooted in something that is not itself causal (causally explainable). The question of why must therefore remain open in the natural sciences, as long as it is not possible to meaningfully unite their foundation anchored in empiricism (measurability) with a well-founded metaphysics, for such a metaphysics is precisely about the reference of what is imaginable to us to its source hidden behind it.

Since natural science as a method of empirically based observation was separated from the field of philosophy in the 17th century or has since been considered an independent discipline, but the supreme discipline of philosophy is epistemology, natural science seems incapable of providing an answer to the question of the meaning or why of our and the cosmos' existence. Philosophical opinions are now to serve in case of doubt as advisors without guarantee of the form of certainty that the "facts" of empirical research provide; in the extreme case Freud's psychoanalysis could be consulted for why-questions or otherwise an intervention of God could be considered (English: God of the gaps - "God as gap-filler").

But if God is an energy potential - as Gödel deduces as strong evidence from his incompleteness theorem and proof of God - then this force, which Plato called pure dynamis, causes the laws of nature, the cosmos and the evolution of animate matter up to us humans, but not the laws of morality, as summarized in the Decalogue, among others. These rules of conduct were invented and enacted by humans, not discovered or uncovered from phenomena like the natural laws; thus the religious gods and the one God of mathematically based epistemology seem incompatible. Gods such as Jehovah entered human history in association with dogmatic beliefs and, according to the teachings of their proponents, held that their truth gained by "revelation" was incontrovertible, so questioning them was considered a "mortal sin against heaven." In contrast to this, the God of epistemology is present through a principle that first implies incalculability on the level of quanta, creatively evolves ('try and error') up to, among other things, Homo sapiens and in this should and wants to be explored (libidinal inquisitiveness, according to Freud, spat out of libido energy). Here, too, 'to err is human': again an implication of freedom (unpredictability of the will).

Ancient Natural Philosophy

Cosmogony as a science began when, in ancient Greece, myth with its subjective truth was opposed to reason, and the attempt to explain the world in its own way was placed above the goal of magically creating meaning. This can be seen in the fact that it was no longer miracle-working gods or heroes but thinking itself that became conscious as a process, capable of focusing on the only thought that was authoritative for it: As the epitome of being, thought conceives itself as the same with this thought. This monism is the core of Parmenides' writing: the unshakable heart of truth, Plato in this respect rightly calls him "our father". Parmenides is the co-founder of a culture based on reason, which struggles to diagnostically illuminate the (pre)historical circumstances that led to the invention of the religious rules of conduct and thus to the beginning of the religious penal fear (eklesiogenic human neurosis).

The currents in Greek natural philosophy, parallel to Parmenides' epistemology, defined the smallest parts (a tomos) that could not be further decomposed, in order to explain natural phenomena, including our brain and its thinking, on the basis of their 'synthetic assembly': Principles that resist further 'analytical' dissection by the human mind. The point was to link everything to everything and, from a single first basic substance or principle, to view the world as a system. Heraclitus, one of the last of the pre-Socratics, calls the world-directing principle Logos, also 'sense' or the 'common' of all conceivable opposites: Sleeping and waking (dreaming and doing), reason and understanding, etc. But they change like the scent of a fire through the herb added to it.

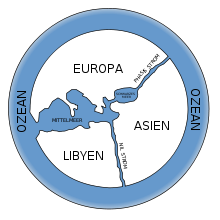

Following this logos, to grasp the outer world whole in the context of meaning with one's own inner self is the intention of natural philosophy, which was founded by the pre-Socratics from about 610-547 BC. The natural philosopher Thales of Miletus' conception of the primordial water on which the land rests resembles the cosmic freshwater ocean of Sumerian mythology, with the world mountain rising in its midst. A remarkable step was taken by Thales' successor Anaximander, who, in his search for the beginning of everything, was the first not to assume a material-material primordial ground (arché) such as water or air, but rather the indeterminate - thought of as determinable or distinguishable from one another (Greek: peirata) - of being things. peirata) - the indeterminable, the unlimited (a peiron) not only opposite, but related to each other: The existing things arise from the apeiron 'ex nihilo' and annihilate each other 'an nihilo' to the same, according to the law of time. Thus an immanterial, mythology-free source of energy was introduced into the physical cosmogony founded by Thales. Out of or better: within this indestructible noumenal source the existing things (phenomena) arise and return to it - as shortly afterwards in Anaximander's successor Heraclitus, who conceives the world as a water that unites earth and ember-air in itself, but arises out of a fire and becomes fire again, as in the exchange of gold for goods and of goods for gold. (...) Fire's turn (=) water, but of water one half earth, the other ember-wind/air. This idea, cast as it were in the form of an equation, integrates the principle of economy and at the same time recalls the principle of equivalence between energy and mass formulated by Einstein.

In his Timaeus Cosmology, Plato (427-347 B.C.) establishes a systematic order of nature (conceptual pyramid of "ideas") in which a creator god (Demiurge), similar to Descartes, constructs the universe, stars, planets and living nature here on earth in a planned manner; truth thus results simultaneously from the beauty (aesthetics) and the goodness (efficiency) of things and beings in their struggle for existence. Even those concepts in Plato's model whose sound is still reminiscent of the mythical concepts of the ancestors have a factual explanatory function: in the dialogue Phaedrus, the Demiurge appears as pure dynamis, devoid of form, colour and smell, which is still above the idea of Parmenidean being. This truth can neither be reduced to the merely empirical, tangible, nor can it be conveyed by way of instruction and external learning, but it can be dug up again from oblivion in the unconscious by methodically assisting thinking in recollection (anamnesis, elenctic).

The cosmological theory of Aristotle (384-322 B.C.) takes over the basic orientation from the Greek mathematician Eudoxos: a spatially finite but temporally infinite world, and spheres that spread out layer-like above the earth at the center. The first cosmic unmoved mover begins on the outside of the spheres, the movement propagates inward until, again, the whole cosmos is driven by a divine force contained in all nature. This god Aristotle equates with logos, reason. For him, the forces (dynameis) in the world were still purely psychic in nature and rooted in myth.

Descartes

René Descartes (1596-1650) made philosophy the basis of thought as a method of knowledge. Knowledge was to be gained exclusively by deduction. He thus took a first step towards the development of a natural science based on subjective certainty by introducing rational methods of knowledge independently and at a diplomatic distance from the idea of the divine. One of the first scientific cosmogonies is contained in his 1644 work Principia philosophiae ("The Principles of Philosophy"). Among its precursors was Aristotle, and subsequently the cosmological theory was taken up by Kant.

With mechanistic models Descartes tried to explain gravitation. The necessary swirls of matter clouds caused by centrifugal forces, whereby the particles imprisoned in them should exchange their energy only in direct contact, explained planetary movements and also the origin of the world system. In contrast to the Christian view, Descartes thus took man out of the centre and at the same time declared the earth to be immovable by means of linguistic twists. A relationship to the church between consideration and rebellion was typical of the 17th century; the latter ended for Giordano Bruno, who like Descartes had professed the Copernican world view, at the stake.

As an explanation of the origin, Descartes has God create a dense pack of matter vortices. The auxiliary construction God as a primeval drive provided the kinetic energy that still exists today.

Kant

Natural philosophical considerations range from Aristotle to Descartes to Immanuel Kant (1724-1804). In his General Natural History and Theory of the Heavens (1755), Kant had established a cosmological theory in which he wanted to unite logos (theory) and myth (history). Descartes scientifically formulated cosmology still needed a God as a causal agent, Kant tried to grasp the order of nature from the history of nature. Kant's theory is philosophically significant, since for the first time without God the planetary system emerges from a cloud of dust, formed solely by the forces of attraction and repulsion, and until the finished state is reached.

Later, Kant drew up a restrictive critique by stating that his cosmological theory would inadmissibly infer generalities conceptually from experience. Applied to today's big bang theory, in which the origin of the world is inferred from observable facts such as cosmic background radiation, Kant's critique could stimulate philosophical reflection.

In 1796 Pierre-Simon Laplace published independently of Kant his so-called nebular hypothesis on the origin of the solar system. Because of the similarity with the Kantian theory, both cosmogonies also became known as the Kant-Laplace theory.

For the current scientific discussion see the

→ Main article: Cosmology

Anaximander: Center of the world

Descartes, Principia philosophiae: Three spheres of the earth

Search within the encyclopedia