Conspiracy theory

In the broadest sense, conspiracy theory is the attempt to explain a state of affairs, an event or a development by means of a conspiracy, i.e. by the purposeful, conspiratorial activity of a usually small group of actors for an often illegal or illegitimate purpose.

In the research literature, a distinction is often made (according to Armin Pfahl-Traughber):

- conspiracy hypotheses (also central control hypotheses) and

- Conspiracy ideologies and conspiracy myths

Conspiracy hypotheses make rational, testable and thus falsifiable or verifiable statements about assumed conspiracies; examples of this are conjectures about the Watergate or Iran-Contra affair, which were made and eventually confirmed before their clarification. Conspiracy ideologies immunize their stereotypical and monocausal ideas about conspiracies from critical revision; an example is the assumption that the 1969 moon landing did not really happen, that the photographs of the moon were taken on Earth. Conspiracy myths are conspiracy ideologies whose alleged conspirators, moreover, are not real people but invented ones. The term conspiracy theory used by the general public is mostly used in the sense of conspiracy ideology or conspiracy myth and is thus used critically or pejoratively.

After precursors in antiquity and the Middle Ages, conspiracy theories appeared in great numbers during the French Revolution. Since 1798, the conspiracy theory has been widespread that these and numerous other phenomena considered to be evil were the work of the Bavarian Illuminati Order, which was banned in 1785. Similar accusations have been made against the Jews since the second half of the 19th century. These anti-Semitic conspiracy theories contributed to the Holocaust. Anti-Semitic and other conspiracy theories have been prevalent in parts of the Islamic world for quite some time. Conspiracy theories were an important part of Stalinism's legitimization of rule. These examples show how conspiracy theories can be used to construct images of the enemy and thus to legitimize violence. Since World War II, they have been directed against the government, especially in the United States. Examples include the assassination of John F. Kennedy or conspiracy theories about September 11, 2001. The emergence of the Internet and right-wing populism have greatly facilitated the spread of conspiracy theories. In this context, misinformation and conspiracy theories about current scientific research findings, such as climate change and vaccinations, spread quickly and uncontrollably and can thus also influence policy preferences.

The question as to the conjunctures of conspiracy theories, i.e. why there were sometimes more, sometimes less of them at different times and in different countries, is answered differently in research. For example, they are regarded as a symptom of crisis, as a remnant of mythical, unenlightened thinking, or, on the contrary, as a phenomenon accompanying the Enlightenment. Psychologically, conspiracy theories can be interpreted as paranoia, although the majority of researchers do not attribute a psychological disorder to the adherents of conspiracy theories. More common are interpretations as projections. Conspiracy theories serve the overburdened individual in overwhelming situations to reduce complexity and maintain a belief in the transparency of reality and the self-efficacy of the subject. The tendency to believe in conspiracy theories seems to be a personality trait according to several studies: People who believe in one conspiracy theory are significantly more likely to believe in others.

From the perspective of the sociology of knowledge, conspiracy theories are presented as a form of heterodox knowledge that is marginalized by being described as such. The word is used partly in a factual-analytical way, partly pejoratively or as a fighting term. In postmodern literature and in light novels, conspiracy theories are a popular subject.

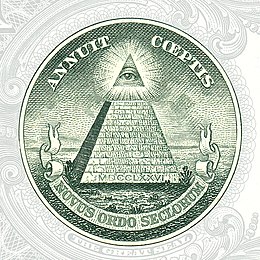

This pictorial element of the one-dollar bill shows an incomplete pyramid, emblazoned with the Eye of Providence and the Latin inscription Annuit coeptis. Below it is the inscription Novus ordo seclorum - for many conspiracy theorists an important proof of a global conspiracy of the Illuminati Order or the Freemasons.

Explanatory notes

The popularity of conspiracy ideologies is subject to fluctuations: In some societies they occur as a mass phenomenon over a period of time, in others they seem to be a constant feature of political culture, while still others are affected only to a small extent. As the historical overview has shown, the era of the French Revolution or years around the Second World War, for example, were periods of conspiratorial boom. Several explanations for these phase changes suggest themselves:

Crisis symptom

Conspiracy ideologies are present precisely where more or less large parts of a society feel threatened from the outside. In this respect, their frequent occurrence can be understood as a symptom of a crisis. This was the case, for example, with the plague of the Middle Ages as well as in Elizabethan England, in revolutionary France at the end of the 18th century, in the 1920s, when the unexpected defeat in the World War and the Treaty of Versailles, which was discredited as a national disgrace, motivated the search for a scapegoat just as much as the real or perceived threat of Bolshevism, during the Cold War and in the current confrontation with jihadism.

Myth

Conspiracy theories in the conspiracyist sense reduce complexity: they resolve confusing and diffuse situations by tracing them back to individual known phenomena and thus making them workable. The situation may still be threatening, but it is no longer inexplicable. According to Hans Blumenberg, myth as a form of processing reality consists in finding and naming the subject of a story in the sense of orienting knowledge. This is exactly what conspiracy theories do: What happens is no longer inexplicable or due to mere chance, but the result of the purposeful activity of presumptive conspirators. In this respect, they contribute to life management and orientation. They do this on a middle level between the world-explaining classical myths and the modern sagas, which are more strongly related to individual cases, but with which they are structurally related: Unlike the classical myth, both make an explicit claim to truth and revolve around prejudices and fear-inducing experiences in the life of a group, which are to be made tangible and manageable by embedding them in a narrative structure. Wolfgang Wippermann describes the frequent occurrence of conspiracy theories as a "turning away from the Enlightenment", as a return of the belief in miracles and demons, which the triumph of rational explanations of the world had actually long since overcome. Norman Cohn suspects not only phenomenological parallels to the chiliastic movements of the Middle Ages, but also a certain continuity, whereby the old religious forms of expression were replaced by secular ones.

This thesis has not gone unchallenged. In fact, a decrease in conspiracy theories in the course of increasing enlightenment cannot be found in all societies. Especially in the 18th century, the age of reason, there was a clear accumulation of conspiracy theories. Something similar can be observed in the USA, a society with a good, if inhomogeneous, educational system: here the popularity of conspiracy theories seems to have remained constant, if not increased, since the end of the Second World War, which is why in 1964 Richard Hofstadter described the "paranoid style" as virtually a characteristic of his country's political culture. There does not seem to be a decline in conspiracy ideologies with increased education.

"Dialectic of Enlightenment"

The connection between conspiracy ideology and reason can also be reversed. Various scholars see a "dialectic of enlightenment" at work here in the sense of Adorno: conspiracy theories are interpreted as "the other of reason", as the shadow side and at the same time the counter-movement of a modernisation and rationalisation of all social relations that is taking place too quickly: With the dissolution by science of all unambiguous sense-giving with a clear claim to truth, with the increasing differentiation and growing complexity of all social relations, with the progressive existential uncertainty of the modern individual, to whom no reference to God explains the contingency of his world any more, the tendency to simple, narrative and community-founding models of interpretation is also growing. If one can no longer explain everything with the work of an almighty God, the tendency grows to attribute unpleasant phenomena to the machinations of a group of conspirators, since someone must be responsible for it. Both the apparent gain in knowledge about the causes of one's own malaise and the shifting of responsibility for it from oneself to the presumptive conspirators have an exculpatory effect. Here, conspiracy theories are also understood as symptoms of crisis, albeit in a broader sense: not for political or economic crises, but for the "crisis of the modern subject." According to the American historian Gordon S. Wood, conspiracy theories became so popular in the Age of Enlightenment precisely because, in the course of the spreading secularization, people no longer believed in God as the cause of all events and instead now attributed all social effects mechanistically to the corresponding intentions of people:

"Having as an alternative only 'providence' as an impersonal abstraction to describe systemic linkages of human actions, the most enlightened minds of the time could only conclude that regular patterns of behavior were the consequences of concerted human intent, that is, the result of several people coming together to further a common plan or conspiracy."

In the 19th century, conspiracy thinking then declined as a result of the developing theories of social life. Michael Butter disagrees: conspiracy theories were rather widespread throughout the 19th century and were considered legitimate knowledge, as can be seen, for example, in the so-called slave power conspiracy theory (see Abraham Lincoln's House Divided speech) or the Kulturkampf in the German Empire. It was only in the 20th century that they were increasingly delegitimized and stigmatized by the social sciences, with the Frankfurt School's studies of authoritarianism and Karl Popper's The Open Society becoming particularly influential. Subsequently, conspiracy theories continued to exist, but they migrated from the centre of social discourse to the margins, as can be seen in conspiracist anti-communism: this was still capable of gaining a majority in the USA during the McCarthy era, but since the 1960s it has only been propagated by the right-wing extremist John Birch Society.

"Conspiracy Theories Are for Losers"

The American political scientists Joseph Uscinski and Joseph M. Parent state: "Conspiracy Theories Are for Losers". In a content analysis of letters to the editor of the New York Times from 1890-2010, they found that when a Republican was president, conspiracy theories were voiced that were suspicious of the Republican Party and big business. On the other hand, if a Democrat was president, the conspiracy theories were directed at their party and alleged socialist conspiracies. In wartime and during the Cold War, they targeted enemies abroad more than in peacetime. In this sense, conspiracy theories functioned as early warning systems of vulnerable groups, helping to initiate collective action in the face of a threat. At the moment when this action would have led to success, they declined significantly.

Internet

The Internet is seen as a cause of the increasing incidence of conspiracy theories that some researchers believe. The reason given is that social media facilitate contact between people with views outside the mainstream, that they allow large amounts of information to be disseminated anonymously, and that the Internet offers the possibility of establishing connections between apparently unrelated facts. Because the latter is precisely the characteristic of conspiracy theories, the American anthropologist Kathleen Stewart pointedly formulates: "The Internet was invented for conspiracy theories: It is a conspiracy theory." The attacks of September 11, 2001, helped make the Internet a major medium for gathering news and information, and thus for spreading the relevant conspiracy theories. "Google WTC 7" was a slogan of the 9/11 Truth Movement. Independent of the filter of the established media, interested people were supposed to form their own opinion with the help of the Google search engine. Soon, however, important websites such as Google and, in particular, Wikipedia came under criticism because they proved to be new gatekeepers against the unchecked spread of alternative explanations.

The Australian philosopher Steve Clark objects to the thesis that the Internet favours conspiracy theories, arguing that it only helps to spread them, but not to develop them. Moreover, it could also limit conspiracy theories, since critical voices could immediately refute them. Joseph Uscinski points out that conspiracy theory websites are not the most visited, rather the opposite. On the Internet, he says, conspiracy theories have a bad reputation. There is no evidence that the tendency to believe in conspiracy theories has increased since the invention of the Internet.

Finally, Michael Butter points out that even in Internet times, conspiracy theories are far from having regained the status of mainstream knowledge that they had until the 1960s. Rather, a fragmentation of the public can be observed: In the German-speaking world, conspiracy theorists have established a counter-public with digital platforms such as KenFM, telepolis or the NachDenkSeiten, which have made conspiracy theory discourse visible to the mainstream. Important conspiracy theory media such as the right-wing populist magazine Compact or the publications of the Kopp Verlag would continue to be distributed primarily in printed form.

Psychology

Psychopathology

Conspiracy theories are structurally similar to paranoia, a mental disorder in which those affected delusionally perceive persecutions and conspiracies against their own person. In both cases, mistrust and suspicion are heightened to an unrealistic level, and in both cases this results in a fearful, aggressive attitude towards the environment perceived as threatening. Richard Hofstadter, for example, pathologizes the tendency to conspiracy fantasy, even though he emphasizes not to use the term paranoia in a clinical sense; various scholars interpret the conspiracy theories prevalent in totalitarian systems as a direct outgrowth of the paranoia of their dictators. The historian Rudolf Jaworski disagrees with this approach, since a conspiracy theory, in order to be effective on a mass scale, must retain stronger references to external reality than an individual delusion; it is also designed for communication and propagandistic dissemination, while delusion patients keep their imaginations to themselves for as long as possible; finally, this interpretation also fails to recognize the instrumental character of conspiracy theories, which are often disseminated against better knowledge in order to achieve certain goals. The German psychiatrist Manfred Spitzer refers to statistics according to which about half of the population of the United States believe in at least one conspiracy theory. To describe all of them as mentally ill is neither meaningful nor purposeful; rather, belief in conspiracy theories is part of the quite normal "arsenal of human world conditions", even though the psychological and neurobiological mechanisms on which it is based are structurally related to those of madness.

Depth Psychology

In depth psychology, conspiracy theories can be explained as projections: The alleged conspirators are assumed to have personality traits which the individual receiving them rejects in himself or which he does not possess: They are portrayed as unscrupulous, cruel, egotistical, exceptionally intelligent, and of a sometimes almost godlike power. The accompanying demonization is often superfluous to explaining the phenomenon that the conspiracy theory is meant to serve; it fulfills less historical than psychological needs. Conspiracy theories, in this interpretation, therefore say something above all about the faults and desires of their authors and readers.

Social Psychology

In 1994, the American sociologist Ted Goertzel examined the influence of various social factors on the belief in conspiracy theories. According to this study, belief in a conspiracy theory increases the tendency to regard other theories as plausible: It correlates with a tendency to distrust state institutions and interpersonal relationships, with job insecurity, and with ethnicity. People who perceived their living situation as unjust and felt left alone by politics were significantly more likely to believe in conspiracy theories, as were African-Americans and Hispanics, which the author associates with their status as ethnic minorities. Younger people were on average more likely to believe in conspiracy theories compared to older people. Few statistically significant results were found regarding education level, gender, or occupational field. Conspiracy theories that particularly affected certain ethnic groups achieved a higher level of agreement among their members: African Americans, for example, disproportionately agreed with claims that the government in Washington had deliberately circulated drugs in the cities, deliberately spread HIV among blacks, and was involved in the assassination of Martin Luther King. This observation was consistent with the results of an earlier survey of African American church members.

According to American psychologists Jennifer Whitson and Adam Galinsky, when mentally healthy people believe they have no control over the situation they are in - that is, people with situationally low self-efficacy expectations - they are more prone to conspiracy theories and superstitions. They then tend to see patterns and connections everywhere - even where there are none - or to associate superstitious rituals with a situation. If you suggest to people that they have lost control of a situation, they will look for support even in apparent chaos. Loss of control is perceived by the psyche as an extremely powerful threat. The strong attempt to restore it can also influence the perception of reality; one creates an imaginary order for oneself with the help of "mental gymnastics". One way is to look for structures to better understand the situation and predict future developments. You look for patterns - and if there are none, you build some in through sensory illusions. One sees patterns and connections which do not exist intersubjectively or objectively. In order to exclude the possibility that the test subjects were generally insecure people who were looking for ordering structures regardless of the context, it was suggested that they were secure. Then the results no longer differed from those of other test subjects. When control is lost, even simple contexts and solutions offered are gratefully accepted. The social psychologist Karen Douglas also points out that - although increased engagement would also be possible - adherents of conspiracy theories tended to feel powerless.

In addition to such low self-efficacy and the perception of having no control over relevant developments, the level of education proved to be a significant factor in the likelihood of believing in conspiracy theories in the studies of the American political scientists Joseph E. Uscinski and Joseph M. Parent: while around 40 % of the subjects without a high school degree showed a high propensity to believe in conspiracy theories, the corresponding proportion of people with a university degree (postgraduates) was well below 30 %. The British social psychologist Viren Swami and his team published a study in 2014 according to which an improvement in analytical thinking (as opposed to intuitive thinking) through prior corresponding training reduces the willingness to believe in conspiracy theories.

The German psychologist Sebastian Bartoschek also comes to the conclusion that it is mainly women from low educational classes who tend to believe in conspiracy theories. Michael Butter, on the other hand, states that belief in conspiracy theories is most common among (white) men over forty. British clinical psychologists Daniel Freeman and Richard P. Bentall found in a 2017 study that the typical conspiracy theorist is male, unmarried, with little formal education and low income or unemployed, a member of an ethnic minority, and without a stable social network. Perceptions of low social participation also contribute to conspiracy mentality, according to a study by American psychologists Alin Coman and Damaris Gräupner. According to Götz-Votteler and Hespers, however, the question of the socio-demographic characteristics that correlate with conspiracism is still unclear overall. The only consensus is that people with politically or religiously extremist views also tend significantly to believe in conspiracy theories.

However, belief in conspiracy theories can also be a means to the end of feeling unique and standing out from the crowd. This is suggested by a study conducted by the University of Mainz, in which participants were presented with a fictitious conspiracy: once with the indication that the majority of Germans believed in the theory, and once with the indication that the majority doubted it. Participants with a strong conspiracy mentality were more likely to believe the theory when it was presented as unpopular. This result was surprising in that people normally intuitively tend to trust a majority opinion more.

According to a study published in 2011 by psychologists Michael J. Wood and Karen M. Douglas of the University of Kent, people who believe in one conspiracy theory are more likely to believe in others, the content of which is less important than the fact that it is a conspiracy theory: For example, among the subjects studied who believed that Osama bin Laden was still alive, that is, that his spectacular killing by American Navy SEALs in 2011 was only faked, there was a high probability that they also believed that he had been dead before they were deployed. Similarly, a correlation could be shown between the assumption that Diana, Princess of Wales had been murdered by British intelligence in 1997 and that she had only faked her death and was still alive. The fact that both assumptions are logically mutually exclusive played at most a subordinate role for the subjects.

Wood and Douglas explain this with a "conspiracist worldview" that manifests itself less in positive belief in the content of certain conspiracy theory narratives than in doubt and distrust of the "official" version. Their statistical (psychometric) study of over 2000 online comments on the subject of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on British and American news websites found that users who leaned toward the conventional explanation were more likely to argue for it than to refute the arguments of conspiracy theorists; conversely, those who believed the attacks were the result of a conspiracy by the American government, the Illuminati, or others were more likely to argue against the official version than for a closed alternative narrative. Adopting a term coined by the American neurologist Steven Novella, Wood and Douglas describe this approach as "anomaly hunting": in the process, the fallacy is drawn from unexplained findings that they cannot be explained at all and would force a refutation of the official version. These users also argued less aggressively, referred more often to other conspiracy theories and rejected the term conspiracy theory as stigmatising.

In 2017, Douglas revised her thesis on the conspiracyist worldview. Now she believes that people prefer conspiracy theory explanations when they offer them epistemic, existential, and social benefits. Thus, she argues, conspiracy theories are particularly attractive to people who have a heightened epistemic need for accuracy and meaning, but who are prevented by lack of competence or other problems from satisfying it in more rational ways. Existentially, conspiracy theories would allow those who believe in themselves to compensate for fears and perceptions of their own powerlessness. The social benefits would relate to everyone's need to maintain a positive self-image. Belief in conspiracy theories allows them to imagine themselves in possession of exclusive insider knowledge and to satisfy other narcissistic needs. The awareness of belonging to an underprivileged or threatened group, whether it be an ethnic group, a political party or a religious community, also increases the likelihood of believing in conspiracy theories. This explains their increased prevalence among African Americans and Muslims.

Sociology of Knowledge

According to Andreas Anton, conspiracy theories are "a special form category of social knowledge", "at the centre of which are explanatory or interpretative models that interpret current or historical events, collective experiences or the development of a society as a whole as the result of a conspiracy." Building on this definition, according to the sociology of knowledge perspective of Andreas Anton, Michael Schetsche, and Michael Walter, the most important function of conspiracy theories is "to interpret events or processes that would otherwise be difficult to classify in a meaningful way, so that they can be integrated into existing world views, structures of meaning, or a certain background knowledge." According to Anton, Schetsche and Walter, conspiracy thinking in modernity is significantly influenced by five interdependent factors: First, there must be a cultural knowledge of the existence of real conspiracies; related to this, there must be mistrust of the social, economic and military power elites, for example through knowledge of their involvement in illegal machinations - they cite the "Gladio affair" as an example; third, there must be a strong desire for explanation of an unexpected event in society, which is not satisfied by the official explanation; fourth, there must be a need for exoneration concerning individual responsibility for an event or social aberrations: Those who assume that the true decisions were made anyway only in a small, uninfluenceable circle of conspirators need not reproach themselves for having voted for the wrong party, if necessary; finally, the possibility of disseminating such heterodox interpretations en masse and unhindered, for example via the Internet, is necessary. Anton, Schetsche and Walter welcome this medium as enabling an "open-ended competition between orthodox and heterodox bodies of knowledge and concepts of reality (including conspiracy theories)".

Michael Butter also assumes that conspiracy theories are considered heterodox knowledge. From the 1960s onwards, they found no place in the mainstream, were marginalised and stigmatised, so that supporters of conspiracy theories had difficulties finding conspiracy texts and like-minded people and publishing their theories. This has changed significantly since around the 2010s thanks to the internet and social media. A veritable counter-public sphere of alternative media such as KenFM, Telepolis, the NachDenkSeiten, Rubikon or the Swiss Infosperber had formed, which explicitly positioned themselves against the traditional quality media and public broadcasting and thereby used the conspiracy theory of the "lying press". Since this was perceptible to everyone on the Internet, the traditional public reacted with great concern about the rise of conspiracy theories and their danger, while the alternative media perceived this with analogous concern as a conspiracy and an attempt to exclude and silence them: Two filter bubbles collide, resulting in a "spiral of agitation." The fragmentation of the social discourse space leads to increasingly irritated communication about and against each other, but "not with each other across the borders of the two publics".

The linguist Clemens Knobloch is of the opinion that the term conspiracy theory has no analytical function in contemporary political and media communication, but rather serves to stigmatise positions marked in this way and those who represent them: "You don't discuss with a supporter of conspiracy theories, you don't need to, and it's not worth it. He is by definition resistant to consultation and unwilling or unable to learn". The word is used to exclude him from discourse, the quality media use it in the sense of an audience insult in reaction to the loss of hegemony they suffer due to their, as Knobloch believes, predictable and too little dissident commentary. This, however, threatens to trigger the opposite effects, he argues, as the accusation of spreading or believing in conspiracy theories sweepingly labels the audience as immature and incapable of discourse. Following this, the linguist Friedemann Vogel criticises the use of language in the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia: Apart from exceptions, the terms conspiracy theory and conspiracy theorist are used in the internal communication there to stigmatize positions that "do not conform to the common ground of the respective ingroup". This is connected with a "disciplining of what can be said" internally and externally, whereby the accusation requires no further specification. Those who merely invoke such a position, or worse, those who attempt to relativize it, run the risk of being barred. This use of the term as part of a communication of power could lead to those who use it being perceived and treated as political actors.

Search within the encyclopedia