Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 consisted of several laws intended to mitigate the contrast between the slaveholding Southern states and the slave-free Northern states of the USA, which had been exacerbated by the massive territorial gains in the Mexican-American War (1846-48).

In 1820, it was agreed in the Missouri Compromise that slavery would be banned in all states north of the Compromise Line (36° 30' latitude) except Missouri. However, due to the victory in the war against Mexico and the peace treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the USA made large land gains south of this line in 1848, so that the balance was shifted in favour of the southern states.

President Taylor brought some firm convictions with him to the White House after his election victory in 1848, one of which was his stance on the slavery issue. Although a slaveholder himself and unwilling to renounce for economic reasons, he rejected the institution on principle. Since the preservation of the Union was his top priority, he did not want to endanger it either by banning slavery in the Southern states or by its expansion. Moreover, an expansion of slavery into the new territories was economically impracticable. Slavery, as the cardinal issue of its time, touched all the political issues Taylor dealt with as president. With regard to the admission of California and New Mexico into the United States, it was a matter of dispute whether this should be done as a free or slave state. Southern congressmen saw the accession of California, which had adopted an abolitionist constitution, and New Mexico as irrevocably upsetting the balance of 15 free and as many slave states in the Senate and weakening their home states. Due to demographic shifts, they were already in the minority in the House of Representatives, which is why they defended their interests ever more rigidly out of concern for further loss of power. In addition, they saw their way of life increasingly threatened by the economic dynamism of the "old Northwest" and the northeastern states as well as the strengthening of the abolitionists there. In return for their consent, they demanded that the president guarantee the future of the slave economy as a whole. Thus, in January 1849, Calhoun called for a caucus of congressmen from the southern states to develop an instrument to protect their interests. Through slaves fleeing to the North, slavery also directly affected free states. The slave states had long been calling for a strengthening of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, i.e. the legislation against escaping slaves. With the applications for membership by New Mexico and California, corresponding threats from the slave states became louder and louder, which even the fact that the president was a slaveholding planter from Mississippi did not change. Even a marginal aspect of foreign policy such as filibuster expeditions took on a hitherto unknown explosiveness. Southerners increasingly equipped such ventures, especially to Cuba, because they wanted to win slaveholding societies as new territories for the Union.

Taylor lost more and more support among the Southern Whigs in the course of 1849 and moved closer to the party wing of the New England and Mid-Atlantic states around Seward and Weed. This also happened because the alliance of Democrats and Free Soil Party in the "old Northwest" visibly threatened the ability of his government to prevail, especially since he was the first president in history to have no majority in either the Senate or the House of Representatives. When Congress reconvened in December 1849 after a two-month recess, the rift between Northern and Southern states became evident. Only after 63 ballots did the election of the Speaker of the House of Representatives succeed, and the threat of secession by the Southern states became a watchword of the crisis. Taylor was so incensed by the separatist threats from the South that he moved even closer to the abolitionist Whigs around Seward. In late January 1850, he pushed Congress for the immediate admission of California and New Mexico into the Union, opposing the principle of "popular sovereignty" at the federal territory level and a western extension of the Missouri Compromise Line. An ulterior motive, according to historian James M. McPherson, was to expose the threat of secession by the southern states as a bluff.

In the Senate, from January onwards, there was such a fierce fight over the membership applications and a new Fugitive Slave Act that it scared the more experienced and moderate MPs. The North-South conflict within the parties went so far that they no longer functioned as a unit. Among the three major politicians of the time - Calhoun, Webster and Clay - it was mainly the latter who, as Senate majority leader, shaped the debate. Clay and Taylor, as leading Whigs in the White House and Congress, would actually have been natural allies, especially since both were slaveholders who opposed the further expansion of slavery. However, they showed no interest in working together. In the debate, Clay, known as the "great compromiser", soon had such a strong presence on the national stage that some suspected the president harboured jealousy of him. By 29 January, Clay had developed a compromise proposal with Webster. Webster belonged to the group of "Cotton Whigs" who supported slaveholders in the South because manufacturing industries in the North, such as cotton mills in New England, were dependent on the large cotton plantations of the South. Their proposal took the form of several resolutions in the Senate and provided for California to be admitted as a free state, for New Mexico and Utah as territories to decide for themselves on slavery, and for Texas to be financially compensated for relinquishing its territorial claims over New Mexico. Furthermore, Clay's compromise proposal included a ban on the slave trade in the District of Columbia and, to satisfy the southern states, a new, more rigid Fugitive Slave Act. The last of Clay's legislative proposals was a proclamation for the free movement of the slave trade between the states. This compromise would have finally broken the balance between free and slave states in the Senate in favour of the North, while giving the South a firmer legal basis for slavery as an institution.

This package of laws was debated in Congress until April without finding a majority. For the North, the Fugitive Slave Act in particular was unacceptable, requiring its citizens to assist authorities in the prosecution of fugitive slaves. On 23 February, Representatives Stephens, Toombs and Thomas Lanier Clingman met with the President and demanded a freeing of slavery in all federal territories in return for an abolitionist state of California. In doing so, they hinted at secession of the southern states if no such compromise could be found. This sparked Taylor's anger. He accused them of threatening rebellion and announced that he would fight any separatist movement with military force. Two days later, Henry S. Foote proposed the formation of a Senate committee to find a majority compromise. It was finally established on 18 April under Clay's chairmanship and consisted of six representatives from each of the northern and southern states. On 4 March, the terminally ill Calhoun made his last appearance in the Senate, taking an extreme position. He threatened secession of the southern states if Congress did not open all territories to slavery, and demanded an amendment to the United States Constitution guaranteeing the southern states equal participation in power. More radical than he was the group of "fire eaters", who considered the North and South irreconcilable and demanded secession. But they were still in the minority with this position. Three days later, Webster appeared, calling for unity and, in the spirit of the Cotton Whigs, for an alliance between the wealthy bourgeoisie of the North and the planter aristocracy of the South. A decisive signal was his approval of the new Fugitive Slave Act. Webster's views were recognised throughout the country and helped to prepare the coming compromise, even if they initially made little difference in the Senate.

Vice President Fillmore was largely ignored in this debate by Taylor, who relied on Seward as a key advisor and ally in Congress. That the president cooperated so closely with an anti-slavery leader led many Southerners to see Taylor as a traitor to their social class. Seward was adamantly opposed to compromise and on 13 March declared before the Senate that slavery was a "backward, unjust and dying institution" that violated God's law of equality for all men. When the president lost his temper after this speech and had a counter-statement printed in the Republic, Seward's opponents hoped that he had lost his influence in the White House. A week later, however, they were back on friendly terms. That Taylor did not fear for slavery as an institution per se despite the protracted debate is shown by the fact that in early June he still instructed his son Richard to buy a new plantation with 85 slaves. The debate remained so heated that even one day before the Senate Committee on Compromise was set up, a shootout between Foote and Benton was only prevented with great difficulty in the Senate chamber.

On 8 May, the Senate committee presented its result, which strongly resembled Clays' original compromise proposal. Taylor was firmly opposed to what he derisively called the "Omnibus Bill", refused to negotiate it with Congress and would have vetoed it if it had passed. This was unlikely for the time being, however, as only a third of Congress was behind the Omnibus Bill. Taylor and most Northern Whigs feared becoming unelectable in the North with the opening of New Mexico and Utah as federal territories to slavery. The President rejected the Fugitive Slave Act proposed by the Senate Committee, the supervision of which was to be a federal matter in the future, as too far-reaching a concession to the slave states. He continued to call for the two-state plan, i.e. to admit California and New Mexico into the Union as states without concessions to the South. By early summer, Clay and Taylor had thus become almost rivals. Eisenhower places the responsibility for this disturbed relationship mainly on Clay, who had always regarded Taylor as a political neophyte and had thus found it difficult to subordinate himself to him. Bauer, on the other hand, cites Taylor as the main reason for the rift between the two. The president found it difficult to give due recognition to the merits of others, which is why he reacted to Clay's great influence in Congress in an offended way. In order to prove that he was not dependent on Clay, he had strongly distanced himself from him. This was reinforced by a specific incident in April 1850 when Clay, lost in thought, did not greet Taylor when they met on the street. The president took this as a personal insult. At this time Taylor, possibly with the support of Clayton, Meredith, Preston and especially Seward, was trying to forge a new coalition of abolitionist Northern Whigs and Unionist Southern Whigs, which bore great similarities to the building of the Republicans as the party of moderate anti-slavery activists by earlier Whigs a few years later.

After the results of the Senate committee were announced, the debate in Congress focused on this compromise proposal and the calls for secession died down. When Clay attacked Taylor's two-state plan on 21 May, their rift was final. The White House responded with a scathing critique of Clay in the Republic and the firing of managing editor Bullitt when he refused to print the text. Gradually a majority for the compromise solution emerged and on 1 July Fillmore warned the president that he would vote for it in the Senate. This was not the only sign of the increasing disintegration of the Taylor administration, for a fortnight earlier the exhausted Clayton had written his letter of resignation as Secretary of State. In the first days of July, several delegations of Southern whigs visited Taylor and tried in vain to dissuade him from the two-state plan. He pragmatically pointed out that he could not risk the votes of the 84 Northern Whigs for the faction of 29 Southern Whigs in Congress. Meanwhile, Taylor's staunchest supporter in the Senate, John Bell, began several days of speeches in the Capitol on 3 July in defence of the two-state plan, which continued even as Taylor lay dying. After Taylor's death, the way was clear for the compromise solution, as it was supported by his successor Fillmore. In September, the five laws forming the Compromise of 1850 were passed, which brought only a temporary solution and did not avert the war of secession in the following decade.

With the Compromise of 1850, California was newly admitted to the Union as a slave-free state. This gave the free states a preponderance of 32:30 votes in the Senate. Texas relinquished territories east of the Rio Grande in exchange for monetary compensation. From these and other territories ceded by Mexico, the New Mexico Territory was formed, comprising the present states of New Mexico and Arizona. In this territory, it was stipulated that the people themselves could decide whether the states should remain slave-free. In the District of Columbia, where slavery was permitted, the trade in slaves was prohibited. In addition, a Fugitive Slave Act was passed, which required US marshals to arrest escaped slaves in the North as well in order to deliver them to their owners.

The Compromise rendered obsolete the Wilmot Proviso, which would have prohibited the extension of slavery to territories acquired from Mexico, but never became law due to the obstructionism of southern senators. The tensions between the states, calmed by the Compromise, grew again through the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 until they ultimately led to the Civil War.

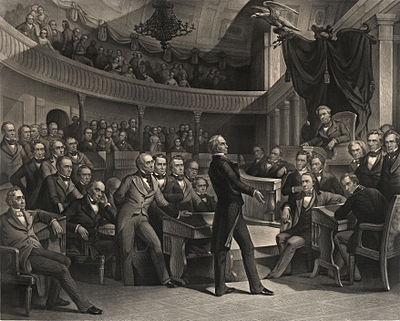

Deliberations on the Compromise of 1850 in the US Senate

Questions and Answers

Q: What was the Compromise of 1850?

A: The Compromise of 1850 was a series of laws passed in 1850 that dealt with the controversial issue of slavery in the United States.

Q: What was the cause of the Compromise of 1850?

A: The Compromise of 1850 was caused by the Mexican-American War, which resulted in the United States acquiring a large amount of new territory.

Q: What did the Compromise of 1850 do regarding California?

A: The Compromise of 1850 admitted California as a free state.

Q: What new territories were created by the Compromise of 1850?

A: The Compromise of 1850 created the new territories of New Mexico and Utah.

Q: How was the dispute between Texas and New Mexico settled by the Compromise of 1850?

A: The Compromise of 1850 settled the dispute over the boundary between Texas and New Mexico with Texas losing the New Mexico territory.

Q: What did the Compromise of 1850 do regarding the slave trade in Washington, D.C.?

A: The Compromise of 1850 put an end to the slave trade in Washington, D.C.

Q: What was the result of the commerce and trade compromise in the Compromise of 1850?

A: The commerce and trade compromise in the Compromise of 1850 ended the slave trade and eventually led to the Emancipation Proclamation.

Search within the encyclopedia