Compass

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Compass (disambiguation).

The compass (from Italian compasso "compass, magnetic needle", derived from compassare "to walk along", plural: compasses) is an instrument for indicating the direction of the earth's magnetic field and thus serves to determine the direction of the north and south poles of the earth and, derived from this, the other cardinal directions. In its simplest form, a (magnetic) compass consists of a freely movable needle made of a magnetic material. The magnetic north pole of the needle rotates towards the magnetic south pole of the earth, which lies close to the geographic north pole in the Arctic.

Other designs are electronic (magnetic) compasses based on Hall sensors or other sensors. With a fluxgate magnetometer, the magnitude and direction of the earth's magnetic field can be determined to within 1/100,000 of its absolute value.

Gyro compasses, whose mode of operation is based on the earth's rotation, work completely without using the earth's magnetic field. The direction is measured with respect to the geographical north-south direction instead of the direction of the field lines of the earth's magnetic field. There are also gyroscopes without directional reference (free gyroscopes such as the heading gyroscope), which must, however, be periodically readjusted. Solar compasses also do not require a magnetic field.

A compass with a bearing device is also called a bussole. Mostly this term is used in surveying technology for precision bearing compasses, but especially in Austria and Italy the simple hiking or marching compass is also called this.

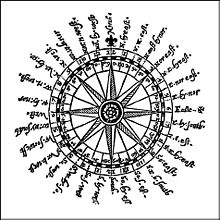

Compass rose from 1607 with division into 32 directions

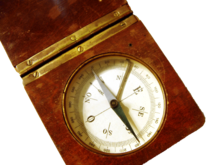

Compass - the letter O stands for "west" in most Romance languages (e.g. Spanish oeste, Italian ovest, French ouest).

History of the magnetic compass

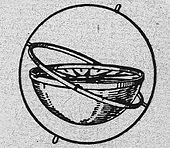

Wet compass

The knowledge that splinters of magnetic ironstone rotate in the north-south direction had been known in Europe since ancient Greece and in China since the time of the Disputed Empires, between 475 BC and 221 BC.

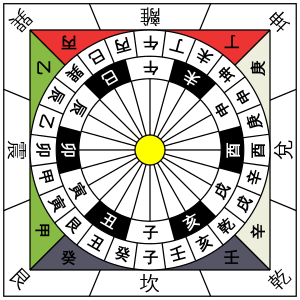

The serious studies on the origin of the compass by J. Klaproth and L. de Saussure lead to the conclusion that the Chinese navigators knew the wet compass already at the turn of the millennium. The Chinese had been using a floating wet compass needle called a southweiser since the 11th century AD. In fact, the south direction is marked as the main direction on the Chinese compass. In the course of time, this developed into special compass forms with a division into 24, 32, 48 or 64 strokes or cardinal points (see Earth Branches). At the end of the 11th century Shen Kuo (1031-1095 AD) recommended in his major work a compass with divisions into 24 directions; shortly after his death such compasses were actually in use.

The sailors of the eastern Mediterranean learned about the wet compass at the latest at the time of the Crusades and optimized it. However, since on the one hand it brought its owner great advantages over the competition and on the other hand it functioned quasi with forbidden magical powers, this knowledge was kept as secret as possible. In Europe, the English scholar Alexander Neckam described the wet compass in 1187 as a magnetized floating needle that was in use among sailors. A writing critical of the church by the French monk Hugues de Bercy also mentioned the floating magnetic needle around 1190 (perhaps even before 1187).

The compass was probably not invented in the Arabian Peninsula, as Arab seafarers at the turn of the millennium had good astronomical knowledge and could navigate well thanks to the steady winds in their region of the world. In the Arabian region, the wet compass can be traced back about one hundred years after Alexander Neckam's mention.

In 1932 Edmund Oskar von Lippmann published a study in which he attempted to prove the alleged superiority of the "Nordic race" by providing arguments for a hypothetical, independent invention of the compass in Europe, without addressing all other previous research. This false theory is still held to some extent today.

Dry compass

The first written mention of a magnetic needle playing dry on a pin is found in the Epistola de magnete of 1269, written by Petrus Peregrinus de Maricourt, which invented the dry compass still used today. A seafarer named Flavio Gioia, whose existence is not certain, is honoured with a monument at the port of Amalfi as the alleged "inventor of the compass". The legend about Flavio Gioia is probably based on a translation error.

The dry compass was more accurate than the floating needle, allowing for more precise and better navigation. In the late 13th century, sailors of the Mediterranean were the first to combine the magnetic needle with the compass rose.

On German, i.e. for the Middle Ages: Hanseatic seagoing ships, the compass was not used until the 15th century; English and southern European seafarers were clearly ahead of them.

Improvements

For multiple meanings or uses of "wind rose", see wind rose (disambiguation).

Around the 1400s, European sailors built the dry compass needle and compass rose into a solid case to station it firmly on their ships. Leonardo da Vinci was the first to propose placing the compass box in a gimbal to further increase accuracy. Starting in 1534, his idea was realized and caught on throughout Europe during the 16th century, giving European sailing ships the most advanced and accurate compass technology of their time. The dry compass came to China around 1600 via Japan, which had adopted it from the Spanish and Portuguese

Discovery of the declination

At the beginning of the 15th century, people in Europe noticed that the compass needle did not point exactly to the geographic North Pole, but - varying from place to place - usually deviated either west or east from it. This deviation is called misalignment or declination. It is not certain who first recognized this. However, it is certain that Georg von Peuerbach was the first to write about the declination. The oldest surviving compass showing the declination was made by Peuerbach. Later, an Englishman - James Cook - took precise measurements of the declination in the areas he travelled and thus provided the basis for a map showing the declination around the globe. By 1542 it was known that there was also a line without declination - the agons. Another Englishman - Henry Gellibrand - discovered that the declination changed over time.

Discovery of inclination

An English compass builder - Robert Norman - noticed that an initially balanced magnetic needle tilted after it was magnetized. He thought of a remedy and weighted down the high end with a weight. He identified inclination as the cause and published a paper on it (Newe Attractive).

The 12 Chinese earth branches (inner circle) and 24 more precise cardinal directions (outer circle). North is down, south is up; west is right, east is left (traditional orientation). If you move the mouse pointer over the symbols/fields, more information is displayed.

ship's compass in a gimballed mounting

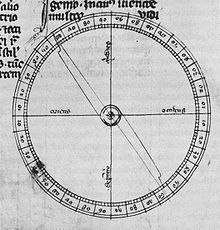

Dry compass, depicted in a copy of the Epistola de magnete from 1269

Design and operation of mechanical magnetic compasses

The classic magnetic compass consists of a rotatable pointer made of ferromagnetic material and a housing in which this pointer is mounted with as little friction as possible. Abrasion-resistant gemstones such as ruby or sapphire are used to support the magnetic needle. An angular scale is usually attached to the case. The pointer itself can have the traditional shape of a needle. In the case of marine compasses, however, this angular scale is located as a complete disc on the needle and there is only a reading line (control line) on the housing.

The pointer aligns itself in the direction of the earth's magnetic field when it is freely movable in all directions. Its field lines run approximately in the geographical north-south direction. Since the deviation is usually known very precisely and is partly recorded in topographical maps, the geographical north direction can be concluded relatively precisely from the direction of the pointer.

Compass capsules are nowadays usually filled with a liquid to dampen the movement of the needle. This makes it vibrate less when shaken, which makes it easier to read without making it harder to settle quickly. The liquid is often a light oil or solvent that will not cause the needle to rust or falter at low temperatures.

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a compass?

A: A compass is a navigational tool that uses magnetism to determine direction.

Q: What does the arrow on a compass indicate?

A: The arrow on a compass points in the direction of the North Magnetic Pole.

Q: Why is a compass an important tool for navigation?

A: A compass is an important tool for navigation because it can help determine direction even in areas with few landmarks.

Q: Who invented the first compass?

A: The first compass was invented by the ancient Chinese in the Han Dynasty.

Q: What was the first compass made of?

A: The first compass was a large spoon-like magnetic object made of magnetite ore set upon a square bronze plate.

Q: When was the first compass invented?

A: The first compass was invented during the Han Dynasty of ancient China.

Q: How does a compass work?

A: A compass works by using a magnetized needle that aligns itself with the Earth's magnetic field, pointing towards the North Magnetic Pole.

Search within the encyclopedia