Comet

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Comet (disambiguation).

A comet or tail star is a small celestial body, usually a few kilometres in diameter, which develops a coma in the parts of its orbit near the Sun, produced by outgassing, and usually also a luminous tail (trail of light). The name comes from ancient Greek κομήτης komḗtēs ("hair star"), derived from κόμη kómē ("main hair, mane").

Comets, like asteroids, are remnants of the formation of the solar system and consist of ice, dust, and loose rock. They formed in the outer, cold regions of the solar system (predominantly beyond the orbit of Neptune), where the abundant hydrogen and carbon compounds condensed into ice.

Near the Sun, the nucleus of the comet, usually only a few kilometers in size, is surrounded by a diffuse, foggy envelope called a coma, which can reach an extent of 2 to 3 million kilometers. The nucleus and coma together are also called the head of the comet. The most striking feature of comets visible from Earth, however, is the tail. It forms only from a solar distance under 2 AU, but can reach a length of several 100 million kilometers with large and near-solar objects. Mostly, however, it is only a few 10 million kilometers.

The number of newly discovered comets was about 10 per year until the 1990s and has since increased noticeably due to automatic search programs and space telescopes. However, most of the new comets and those observed in previous orbits are only visible in telescopes. As they approach the Sun, they begin to glow more strongly, but the evolution of brightness and tail cannot be predicted precisely. There are only about 10 really impressive apparitions per century.

Comet Churyumov-Gerasimenko, imaged by the Rosetta space probe (2014)

Hale-Bopp, taken on 11 March 1997

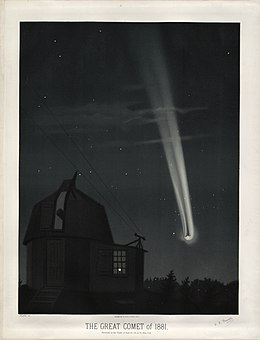

The Great Comet of 1881 (drawing by É. L. Trouvelot)

History of comet research

→ Main article: Comet research

Even in early times, comets aroused great interest because they appear suddenly and behave completely differently from other celestial bodies. In ancient times and up to the Middle Ages, they were therefore often regarded as messengers of fate or signs of the gods.

In antiquity, during the observation of a conjunction with the naked eye, there apparently occurred a fusion of a planet with a star, which is mentioned by Aristotle in his writing "Meteorologica" and was regarded as a possible cause for the formation of comets. It is apparently the event that took place in Greece about ten years before the writing, in the morning hours of July 13, 360 B.C., on the eastern horizon, where the smallest angular distance between the ecliptic star Wasat and the planet Jupiter in the constellation Gemini was only about 20 minutes of arc. Based on the fact that no comet was formed in this event, Aristotle ruled out such events as a cause for the appearance of comets. Aristotle and Ptolemy therefore considered comets to be evaporations of the Earth's atmosphere.

Only Regiomontanus recognized independent celestial bodies in the comets and tried to measure an orbit in 1472. The oldest printed text on comets is probably the Tractatus de Cometis, published in Beromünster in 1472 and in Venice in 1474, by the Zurich city doctor Eberhard Schleusinger, who was born in Goßmannsdorf near Hofheim in Lower Franconia and whose work forms the basis for Johannes Lichtenberger's Pronosticatio. Tycho Brahe's discovery that comets are not phenomena of the Earth's atmosphere can be regarded as the beginning of scientific comet research. For he determined with the comet of 1577 that it must be at least 230 earth radii away. However, it took many decades before this assumption was accepted, and even Galileo contradicted it. In 1682, Edmond Halley succeeded in proving the tail star that appeared in that year to be a periodically recurring celestial body. The comet, which was also observed in 1607, 1531 and 1456, moves on an elongated ellipse around the sun in 76 years. Nowadays an average of 20-30 comets are discovered per year.

The state of knowledge about comets around the middle of the 19th century can be taken from Scheffel's humorous song Der Komet: "Even Humboldt, the old man of explorative power, ...: 'It fills the comet, much thinner than foam, With all-smallest mass the very largest space?'"

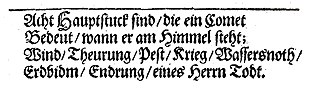

Verse from 1661 about the effects of a comet

Overview

Characterization

Comets are divided into aperiodic comets and periodic comets on the basis of their appearance interval. The latter are divided according to their orbital periods into long-period and short-period comets.

Aperiodic comets

Comets, which - due to their parabolic or hyperbolic orbit - certainly do not recur, or single observations, about which - due to lack of exact orbit determination - no statement can be made yet.

Periodic comets

Comets whose recurrence is assured by their orbital elements, i.e. which orbit the Sun in a stable orbit - at least for a certain period of time.

- Long-period comets with an orbital period of more than 200 years probably come from Oort's Cloud, their orbital inclinations are statistically distributed and they orbit the Sun both in the same sense of orbit as the planets (prograde) and in the opposite direction to the planetary orbits (retrograde). The eccentricities of their orbits are close to 1 - but the comets are usually still bound to the Sun by gravity, although it takes them up to 100 million years to complete their orbits. Eccentricities greater than 1 (hyperbolic orbits) are rare and are caused mainly by orbital perturbations as they pass the major planets. These comets then theoretically do not return close to the Sun, but leave the solar system. In the outer part of the planetary system, however, even small forces are sufficient to make the orbit elliptical again.

- Short-period comets with orbital periods of less than 200 years probably originate from the Kuiper belt. They usually move in the usual sense of orbit and their inclination is on average about 20°, so they are close to the ecliptic. For more than half of the short-period comets the largest solar distance (aphelion) near the orbit of Jupiter is 5 and 6 astronomical units (Jupiter family). These are originally longer-period comets whose orbits have been altered by the influence of Jupiter's gravity.

Designation

→ Main article: Naming of asteroids and comets

Newly discovered comets are first given a name by the International Astronomical Union, consisting of the year of discovery and a capital letter, starting with A on 1 January and B on 16 January in a half-monthly rhythm (until Y on 16 December, the letter I is skipped) after the date of discovery. In addition, a number is added so that several comets can be distinguished in the half month. As soon as the orbital elements of the comet are determined more exactly, another letter is prefixed to the name according to the following system:

| P | the orbital period is less than 200 years or at least two confirmed observations of the perihelion passage (periodic comet) | |

| C | The orbital period is greater than 200 years. | |

| X | The trajectory cannot be determined. | |

| D | Periodic comet that was lost or no longer exists. | |

| A | It is subsequently discovered that it is not a comet, but an asteroid. |

Comet Hyakutake, for example, is also listed under the designation C/1996 B2. So Hyakutake was the second comet discovered in the second half of January 1996. Its orbital period is greater than 200 years.

Usually a comet is additionally named after its discoverers, for example D/1993 F2 is also called Shoemaker-Levy 9 - it is the ninth comet discovered by Eugene and Carolyn Shoemaker together with David H. Levy.

Comet Orbits

Since only short orbital arcs have been observed for newly discovered comets, parabolic orbits are calculated first. However, since a parabola is only a mathematical limiting case and cannot occur as such in nature (any disturbance, no matter how tiny, turns it into an ellipse or a hyperbola), comets whose orbital eccentricity is given as e = 1.0 (= parabola). actually run either on ellipses (e < 1.0) or on hyperbolas (e > 1.0). With longer observation and the acquisition of additional astrometric positions, it can then be decided whether they are ellipses or hyperbolas.

From about 660 examined comets the following distribution can be seen: 43 % parabolas, 25 % long period ellipses (orbital period over 200 years), 17 % short period ellipses (orbital period up to 200 years) and 15 % hyperbolas. However, the high proportion of parabolas is due to the too short observation period of many cometary phenomena, where long-period ellipses cannot be distinguished from a parabola. With a longer visibility of 240 to 500 days only 3% of the comets probably still describe a parabolic orbit. Thus the ellipses are likely to be predominant.

Discovery and observation of comets

→ Main article: Visibility of comets

While until 1900 about 5 to 10 new comets were discovered per year, this number has risen to more than 20 in the meantime. This is mainly due to automatic sky surveys and observations by space probes. But there are also amateur astronomers who have specialized in comet search, especially in Japan and Australia.

The most successful was the New Zealander William Bradfield with 17 discoveries between 1972 and 1995, all of which were named after him. He systematically searched the twilight sky up to 90° solar separation and spent about 100 hours a year on it.

For visual observations, fast binoculars or a special comet finder are suitable. A low magnification at high luminosity is important to preserve the relatively low surface brightness of the comet (similar to nebula observations). The exit pupil should therefore correspond to that of the dark-adapted eye (about 7 mm).

Today, cameras with highly sensitive CCD sensors are mostly used for photography. For detailed photographs (e.g. of the structure of the comet's tail), the camera does not track the stars, but the comet itself by means of an approximate orbit calculation. Most of them are still in the outer solar system when they are discovered and appear only as a diffuse star of 15th to 20th magnitude.

Space probes to comets

The following table lists some comets that have been visited or are planned to be visited by space probes:

| Name | Discovery | Space probe | Date | Closest approach | Comments |

| Borrelly | 1904 | Deep Space 1 | 2001 | 2200 | Flyby |

| Giacobini-Zinner | 1900 | ICE | 1985 | 7800 | Flyby |

| Grigg-Skjellerup | 1902 | Giotto | 1992 | 200 | Flyby |

| Halley | known since ancient times | Giotto | 1986 | 596 | Flyby |

| Hartley 2 | 1986 | Deep Impact, | 2010 | 700 | flyby, |

| Temple 1 | 1867 | deep impact | 2005 | 500; | Impact + flyby |

| Churyumov-Gerasimenko | 1969 | Rosetta | 2014 | 6 or 0 | Orbit of Rosetta; landing of lander Philae on Nov. 12, 2014, |

| Game 2 | 1978 | Stardust | 2004 | 240 | Fly-by and return to Earth (Sample return mission) |

For comparison, June 2018 Hayabusa 2 probe approaches within a few kilometers of asteroid Ryugu.

Play media file Animation of a comet orbit

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a comet?

A: A comet is a ball of mostly ice that moves around in outer space. They are often described as "dirty snowballs".

Q: How do comets differ from asteroids?

A: Comets have higher orbital inclinations than asteroids, and they are usually found farther away from the ecliptic plane where most solar system objects are located.

Q: What causes comets to have tails?

A: Comets have long tails because the Sun melts the ice, creating gas and dust which is then blown away by the solar wind.

Q: What is the nucleus of a comet?

A: The nucleus of a comet is its hard centre, and it has one of the lowest albedos (reflectivity) in the solar system. When light shone on Halley's Comet's nucleus, only 4% was reflected back to us.

Q: Are there different types of comets?

A: Yes, there are periodic comets which visit again and again, and non-periodic or single-apparition comets which visit only once. Some comets also orbit together in groups which astronomers think may be broken pieces that used to be one object.

Q: Can comets break up?

A: Yes, some comets can break up over time due to gravitational forces or collisions with other objects such as planets or asteroids. For example, Comet Biela broke up in the 19th century and Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 broke up before hitting Jupiter in 1994.

Q: Where do most comets come from?

A: Most comets come from the Kuiper belt which is very far away from the Sun but close enough for us to see them at night when they pass near Earth.

Search within the encyclopedia