Colonialism

Colonialism is the seizure of foreign territories and the subjugation, expulsion or murder of the local population by colonial rule. Colonists and colonized people are usually culturally alien to each other, which was associated with the colonial rulers in modern colonialism with the belief in a cultural superiority over the so-called "primitive peoples" and partly in their own racial superiority. This notion was supported by early theories of sociocultural evolution. The colonization of the world by European nations fostered the ideology of Eurocentrism. Private individuals, companies, and states participated as actors, most of whom initially promoted or secured colonizations. In the longer term, almost all of the colonies established ended up in state hands.

The term colonialism refers not only to the political facts of colonial rule, but also to a historical phase, the colonial era (age of colonialism), which begins with the modern era: since Christopher Columbus' voyages to America at the end of the 15th century (1492 is sometimes regarded as the year of transition from the Middle Ages to the modern era), European powers formed colonial empires overseas, first Spain and Portugal, soon followed by the Netherlands, Great Britain and France. Colonialism went hand in hand with European expansion. The end of the colonial era lies between the first declarations of sovereignty after the French Revolution (1797: USA, Haiti) and the end of the Second World War (1945) and the founding of the UN as a concept of equal nations worldwide. Yet the 19th century in particular was marked by a late colonialism of new geopolitical actors, including former colonies. In the end, Belgium, Italy and Germany were also involved in the race for the colonial division of Africa in the 19th century; in Asia, Russia in particular sought to expand; and at the turn of the 20th century, the USA and Japan were added as colonial powers. In addition to economic profit expectations and the securing of future raw material bases, power rivalry and questions of prestige played an important role among the motives that drove colonialism in the age of imperialism - of which colonialism forms a partial aspect. For the outgoing colonial era, one also speaks of postcolonial and an age of decolonization, especially in the mid-20th century, although imperialist aspirations continue to this day, and are even strengthening again, which is why the term neocolonialism appears.

Colonialism is conceptually and meaningfully closely related to colonization. From older times, for example, the ancient Greek colonization in the Mediterranean region and the medieval German colonization of the East are known. The forms, extent and modes of action of modern colonialism appear in a wide range of different manifestations. Both in the political metropolises of colonial rule and in the periphery of the associated colonies, the individual colonial powers unfolded a broad spectrum of peculiarities with regard to organisation and the exercise of power, as well as in the participation of colonised people in the ruling apparatus on the one hand and in the repression of the colonial peoples on the other. This also had an impact beyond the actual colonial period in the course and consequences of decolonisation.

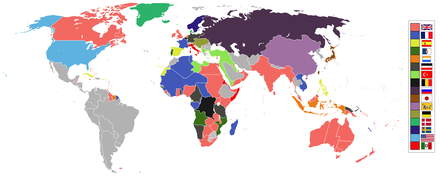

Colonial empires in 1898 , before the Spanish-American War, the Boxer Rebellion and the Second Boer War. United Kingdom France Spain Portugal Netherlands German Reich Ottoman Empire Belgium Russia Japan China (Qing Dynasty) Austria-Hungary Denmark Sweden-Norway USA Italy Independent/Other countries

Economic and social motives and characteristics

Byzantines and Saracens dominated the Mediterranean until the 11th century. The fight against the Saracen threat, which extensively practiced piracy, by Pisa and Genoa, ended their domination. Later, the Italians themselves practiced piracy, especially on the coasts of Asia Minor. Privateering companies were often formed to finance such ventures, and often it was not even possible to distinguish between trade missions and piracy. For the inhabitants of Andalusia, too, the capture of Moorish ships and the landing on African coasts, where they robbed and turned captives into slaves, constituted a lucrative business. Due to the repression of Arab-Syrian traders in the course of the Crusades, the Italian city-states were now also able to trade directly with the Levant and the Orient. Especially the European population growth since about 1000 (peak around 1300) boosted this long-distance trade.

The crisis of the 14th century with the plague and urban exodus also affected the nobility. As a result of the gradual decline of feudal structures, the nobility had concentrated on luxury goods as a sign of a lifestyle befitting their status. Due to the anarchic conditions during the Reconquista, the nobles, especially in Castile, were able to secure large land grants from the Spanish king. The regular incursions into the (still) remaining Moorish lands of the Iberian Peninsula had also become important sources of income for the latter. The nobility also became increasingly involved in economic ventures such as the tuna trade (which was as important for food and trade as the salt herrings in northern Europe) and built up their own fleets for this purpose. The European discovery of Guinea's Gold Coast therefore also involved ships of the nobility from the beginning. And also the settlement of islands in the Atlantic was started by great vassals of the Spanish king; only later the crown itself followed.

Access to the luxury goods of the Orient (carpets, spices, dyes, etc.), which were coveted throughout Europe, could only be obtained through Arab middlemen. Thus Egypt controlled the trade in Arab and Indian goods. Although European traders were welcome, onward travel for foreigners beyond Cairo was forbidden. The so-called "Latin" trade route that bypassed this "Muslim blockade" had been blocked since the end of the 14th century: After the collapse of the vast Mongol Empire founded by Genghis Khan, especially through Timur Lenk's conquests and the national revolution of the Ming dynasty in China, the "Mongol route" was closed to Italian merchant caravans. The advance of the Ottomans in the 15th century further complicated the Italians' trade with Asia. The Orient was thus closed to Europe.

The initial situation of European overseas expansion, which heralded the age of colonialism, was thus partly determined by the endeavour to open up alternative trade routes to the long-distance trade networks (trade with India) controlled by the Ottoman rulers and asserted against the grasp of the Europeans. Bartolomeu Dias opened the way to the Indian Ocean by sailing around the Cape ofGood Hope in 1488, which enabled Vasco da Gama to reach India by ship in 1498. From their Indian base at Goa, the Portuguese managed to reach Malacca in 1509 and conquer it under Afonso de Albuquerque in 1511. The Atlantic crossing by Columbus in 1492 led to the beginning of the European exploration, conquest and settlement of the Americas.

Raising capital for the costly voyages of discovery had become easier due to advances in the monetary and credit systems. The emergence of the first banks in northern Italian city-states simplified the pooling of larger amounts of money for the expensive overseas ventures. Since the prospects of profit were very vague, the state often assumed the cost of sea expeditions to mitigate the high risk. Private companies usually participated only in chartering the ships with food and barter goods and received a fixed portion of the profits from the voyages in return. However, the overseas voyages of discovery were made possible not least by the development of the new type of ship, the caravel, which was distinguished among other things by its improved manoeuvrability under changing wind conditions.

The opening up of the West African coast by the Portuguese was followed by imports of slaves and gold to Europe. The ruling dynasty, which had a one-fifth share in the economic proceeds of this kind, remained interested in further expansion for its part. What this was all about is shown by designations such as "Ivory Coast", "Gold Coast" or "Slave Coast".

Gold and silver

The African gold trade was controlled by Muslim traders who brought the gold by caravan to the coasts of North Africa and thus also served European demand. In 1456, the Portuguese established the first trade link to the African gold zones. From 1475 onwards, gold was then brought to Portugal in large quantities by ship via Guinea in barter trade with sub-Saharan Africa, without any detour via Muslim traders. Nevertheless, due to the expensive purchase of oriental luxury articles and costly European wars, there continued to be a net outflow of gold from Europe for the time being.

Columbus also sought to highlight the wealth of gold as a special feature during his voyage of discovery to Caribbean America. The areas conquered by the Spaniards became a supposed El Dorado in the gold rush that set in after Pizarro had extorted over 13,000 pounds of gold and 26,000 pounds of silver from the Inca ruler Atahualpa. The silver deposits in Bolivia and Mexico, which were discovered before 1550 and immediately shipped to Europe, caused prices throughout Europe to rise by 400 percent as late as the 16th century.

Slave Trade

→ Main article: Atlantic slave trade

Since the High Middle Ages, the notion that Christians should not be made slaves has prevailed, and as Christianization progressed, slaves became a scarce "commodity" in Europe. There was an increased shift to the slave trade with the Levant from the 13th century onwards. At first, Muslim traders supplied them mainly from the Crimea, and from the 15th century onwards especially from the Balkans, where the Ottomans abducted Christians as prisoners of war and sold them to European, above all Italian, traders. Catalan slave traders, on the other hand, carried off their victims mostly from Asia Minor. The conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by the Ottomans, however, led to a decline in slave shipments from the Levant and resulted in price increases in Italy. Europe then reoriented itself towards slaves from Black Africa, which brought Muslim trade caravans to the North African coast.

On the Caribbean islands, sugar cane cultivation became the linchpin of colonial rule. After the extermination of almost the entire indigenous population, large areas were available for this purpose; African slaves were now "imported" on a large scale as labour. Catch and transport were organised by Europeans, Africans and Arabs in cooperation. The mortality rate during the ship passage under undignified conditions across the Atlantic alone was between 25 and 40 percent. The draconian punishments imposed on slaves in mines and on plantations meant that few of them lived beyond the age of 35. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the triangular trade flourished: European consumer products, often of inferior quality, were exchanged for slaves in Africa; these were shipped in chains across the Atlantic, mostly to the Caribbean, from where the ships then returned to Europe loaded with colonial goods such as sugar, rum, indigo, and more.

Colonial exploitation and cost-benefit relations

Like the Spanish and Portuguese, all later colonial powers sought to derive economic benefit from their colonial possessions - as they did in the partition of Africa. However, this was not preceded by a rational cost-benefit analysis. "Rather, after the acquisition of new territories, perplexity often set in as to what economic potential they possessed, how they should be administered, and what benefits they might bring to the mother country." Conquest was usually followed by three to four decades of predatory economics. Barter and overexploitation of resources dominated; investment in infrastructure was almost nonexistent.

The strongest economic link within the colonial empires proved to be the monetary association. France was particularly consistent in this respect and thus created a monetarily uniform colonial empire, which in Africa resulted in the francophone states maintaining close monetary relations with France even after their independence.

While the colonial powers' own cost-benefit balance with regard to their spheres of influence could be partly ambivalent and partly negative, the colonized were mainly exposed to plunder. Thus, during the decades of intensive economic relations with their mother countries, the colonies and semi-colonies of the European powers in Asia and Africa remained poor and backward, as did the semi-colonies of the USA in Latin America, while developments in Europe and North America showed a rapid increase in social prosperity. In 1914 nearly one-fourth of French capital investments abroad went to Russia, while barely 9 percent went to the French colonies. Germany's foreign investments before the outbreak of the First World War went to the colonial protectorates even to only 2 percent.

The comparatively late colonial power Japan was the only one to establish a planned industrial colonial economy in its sphere of influence, for example coal, iron and steel in Korea and Manchuria or cotton processing in Shanghai and northern China. The aim was to compensate for the lack of raw materials on the Japanese islands and to establish a large Asian economic area under Japanese control based on the division of labour. According to Osterhammel, this was the most repressive colonial regime in modern history; nevertheless, it left important foundations for further industrial development in Korea, Taiwan and parts of China.

States that were not colonial powers also benefited from colonialism. Switzerland, for example, never had any colonies of its own. Swiss explorers, missionaries and traders were, however, welcome by almost all colonial rulers thanks to Switzerland's status of neutrality and the good connections of the Swiss upper class. Scientists made stellar careers through colonial expeditions. They sent enormous quantities of found and stolen objects to Switzerland, which became the basis of the ethnological and natural science collections of several museums. Swiss families amassed fortunes through the slave trade. African children and youths without names worked in Switzerland as liftboys. The colonial commodity cocoa became a box office hit as Swiss chocolate.

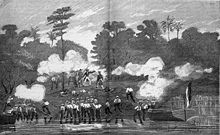

Commander Bouët-Willaumez attacks insurgents near Grand-Bassam (Ivory Coast), engraving from 1890

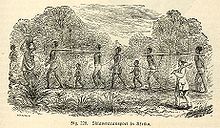

Depiction of a slave ship (19th century)

With the lowering of the Japanese flag on September 9, 1945, in front of the Governor General's residence in Keijō, the official transfer of administration of the southern part of Korea (as the Japanese colonial province of Chōsen), to the Americans is completed.

Ideological-programmatic aspects of colonial regimes

The colonial regimes of European powers since the 16th century needed justification and compatibility above all with the Christian religion that linked the colonizing conquerors with their European sender metropolises. The doctrine of "just war" against non-Christians, inherited from the Middle Ages, could provide the basis for this when criticism arose against the Spanish conquests in Central and South America, invoking the New Testament's prohibition of violence. With the papal bull Inter caetera in 1493 the Spaniards had been granted the rights to new countries in America, to which they were to bring the Catholic faith.

In the early modern period, the notion of Europeans' own cultural superiority over other cultures such as Chinese, Japanese, Indian, or Muslim was still little developed, although European colonizers in the Americas also transmitted other accents and impressions when entire great empires broke apart under the grip of conquistador troops: "The Europeans with their white skin, horses, and shotguns appeared as gods. They began to feel themselves superhuman."

According to Osterhammel, however, a thoroughgoing European sense of mission vis-à-vis the other established cultural areas of the world only prevailed in the era of the transatlantic revolutions in the late eighteenth century, when "the West" prepared to usher in a whole new age of freedom and equality, and this was combined with the economic dynamism of the industrial revolution that was getting underway, which affected North America as well as Europe. Osterhammel names the basic elements of colonialist thought "in its mature late form" as follows: 1. the notion of irreconcilable foreignness or "otherness" in connection with a relationship of superiority and inferiority; 2. the belief in mission in connection with the duty of guardianship; 3. the utopia of policy-free colonial administration.

From the idea of the anthropological "otherness" of the colonized, their different physical and mental disposition, their inability to produce deeds and works similar to those of modern Europe was inferred. The presupposed difference was asserted for various fields as needed: among others, as "pagan depravity", as technological inferiority in the mastery of nature, as a (tropically) climatically weakened human constitution, and finally as racially conditioned inferiority. The latter was largely unanimously held to be true by Europeans and Americans, at least during the last three or four decades before the First World War.

The assumed anthropological difference served to justify a duty of guardianship of the Europeans or "whites" as the superior civilization or race ("the white man's burden"). Not exploitation but mutual complementation of both sides was propagated. This included the view, widespread since the late 19th century, that the "developed" West had not only the right but also the duty to develop the natural resources of tropical countries; since the natives were unable to do so, Europeans and Americans, by taking this on, would be doing a service not only to themselves but to all mankind. A superior minority, he said, had a responsibility to the backward majority of people. "Colonial rule was glorified as a gift and an act of grace from civilization, a kind of permanent humanitarian intervention. The burden of the task was so immense that there was no thought of its speedy accomplishment."

Since Europeans saw the conditions found in colonial territories as chaotic, they viewed their actions on the ground not as arbitrary rule but as creating order. In this perspective, however, colonial administration always remained susceptible to the suppressed "anarchy" and "impulsiveness" among the colonized. Accordingly, one could not allow oneself any weakness, since otherwise troublemakers would be encouraged, even a "Negro uprising" could break out. From this point of view, Western forms of politics were not suitable for colonial areas: "Nothing should disturb the peace of efficient administration.

Where military power was exercised in the colonies, internal peace was to prevail at the same time by disarming the native population in the manner of the "Pax Britannica". One tried to activate the colonized mainly through "education for work". For non-Europeans, however, this was often only a transparent cover for exploitative conditions and had nothing to do with qualification for independence. Whenever this education seemed futile to the colonial authorities, the natives were often exposed to arbitrary forms of cruelty without protection. An extreme example of this is the extermination order of Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha against the Herero people and the subsequent action of German colonial troops in 1904 in German Southwest Africa.

African slave trade

Questions and Answers

Q: What is colonialism?

A: Colonialism is when a more powerful, richer country takes control of a smaller, less powerful region or territory outside of its borders.

Q: How did colonial nations protect settlers from the indigenous people who were pushed aside?

A: Colonial nations often set up a military fort or colonial police system to protect settlers from the indigenous people who were pushed aside.

Q: Why do some countries use colonialism?

A: Some countries use colonialism to get more land for their people to live in, to extract resources such as trees (wood), coal, or metals, or to create a local government or military fort. Other countries use colonialism so that they can get workers from the poorer country to work in factories or farms (either in the richer country, or in the poorer country).

Q: In which centuries was colonialism most prominent?

A: Colonialism was most prominent during the 15th, 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

Q: Which European countries established colonies during this time period?

A: During this time period many of the richer and more powerful European countries such as Britain, France, Spain and Netherlands established colonies in Africa South America Asia and Caribbean.

Q: How did these European countries acquire land for their colonies?

A: These European countries acquired land for their colonies by helping settlers move into new areas and by using force and violence against indigenous peoples living on those lands.

Q: Did colonial powers ever force people from poorer colonized regions into slavery?

A: Yes, in the past powerful colonizing nations sometimes forced people from poorer colonized regions into slavery.

Search within the encyclopedia