Coffee

![]()

The title of this article is ambiguous. For other meanings, see Coffee (disambiguation).

Coffee (standard pronunciation in Germany: [ˈkafeː]; in Austria and Switzerland: [kaˈfeː] ![]() colloquially in northern Germany also [ˈkafə]

colloquially in northern Germany also [ˈkafə] ![]() ; from Turkish kahve from Arabic قهوة qahwa

; from Turkish kahve from Arabic قهوة qahwa![]() for "stimulating drink", originally "intoxicant", also "wine",) or coffee drink is a black, psychotropic, caffeinated beverage made from roasted and ground coffee beans, the seeds of the fruit of the coffee plant, and hot water.

for "stimulating drink", originally "intoxicant", also "wine",) or coffee drink is a black, psychotropic, caffeinated beverage made from roasted and ground coffee beans, the seeds of the fruit of the coffee plant, and hot water.

The degree of roasting and grinding vary depending on the method of preparation. Coffee contains the vitamin niacin. The term "bean coffee" does not mean that the coffee is still unground, but refers to the purity of the product (Arabic bunn بن "coffee beans", Amharic bunaa ቡና "coffee") and serves to distinguish it from substitute coffee (made from chicory, barley malt, etc.). Coffee is a stimulant.

Coffee beans are obtained from drupes of various plant species from the Rubiaceae family. The two most important species of coffee plant are Coffea arabica (Arabica coffee) and Coffea canephora (Robusta coffee), with many varieties and cultivars. There are different levels of quality depending on the variety and where it is grown. Coffee is grown in over 50 countries worldwide. There are 124 wild coffee species, of which about 60% are considered endangered.

Light roasted coffee beans

Raw coffee beans

Coffee Tree

cup of coffee

Production

Economic importance

A total of 10,035,576 tonnes of green coffee was harvested globally in 2019. The table provides an overview of the 10 largest producers of coffee worldwide, which together harvested 84.3% of global production:

| Harvest volumes 2019 (in t) | |

| Country | Harvest |

| Brazil | 3.009.402 |

| Vietnam | 1.683.971 |

| Colombia | 885.120 |

| Indonesia | 760.963 |

| Athiopia Ethiopia | 482.561 |

| Honduras | 476.345 |

| Peru | 363.291 |

| India | 319.500 |

| Uganda | 254.088 |

| Guatemala | 225.000 |

| remaining countries | 1.575.335 |

| Source: FAOSTAT | |

At least 20 to 25 million families worldwide depend on coffee farming for their livelihoods. "Assuming an average family size of five, more than 100 million people depend on coffee [cultivation]."

About ten percent of roasted coffee is sold as decaffeinated coffee (2004 figure).

Trade

In 2016, the global export of coffee was worth 19.4 billion US dollars. More than two thirds of the global green coffee trade was handled via Switzerland. Germany was the fifth largest exporter with a value of 991.6 million US dollars.

Coffee is not the "world's second most important [legal] trade product after petroleum, [but is] the second most valuable trade product exported by developing countries." For some countries, such as East Timor, it is the only significant export. Coffee revenues have fluctuated widely, falling from $14 billion in 1986 (a record at the time) to $4.9 billion in the crisis year of 2001/2002. This so-called coffee crisis - which lasted several years - has had consequences for coffee producers around the world.

Attachment

Coffee Plants

For the production of the coffee beverage, mainly the species Arabica and Robusta are used, to a lesser extent the species Liberica and Excelsa. The first yields are produced by bushes that are three to four years old; from the age of about 20 years, the yield per bush declines.

In 2005, there were around ten billion plants of the Arabica species (Coffea arabica) and around four billion of the Robusta species (Coffea canephora). Together, these two species provide 98% of the green coffee produced worldwide. Robusta coffee comes mostly from West Africa, Uganda, Indonesia and Vietnam, but also from Brazil and India. Arabica coffee is grown mainly in Latin American countries, East Africa, India and Papua New Guinea. According to a 2002 Oxfam study, 70% of coffee comes from smallholder farms.

See also: "Cultivated coffee species" in the article: Coffee (plant)

Climate

Coffee shrubs (or trees) need a balanced climate without temperature extremes, without too much sunshine and heat. Average temperatures should be between 18 and 25 °C, not exceeding 30 °C and not frequently dropping below 13 °C; the plants do not tolerate temperatures below 0 °C. The water requirement is 250 to 300 millimetres per month, which is why the annual rainfall must be 1500 to 2000 millimetres; if the annual rainfall is less than 1000 millimetres, coffee is irrigated; if the annual rainfall is less than 800 millimetres, coffee is not grown. Robusta coffee requires higher amounts of rainfall than Arabica coffee. A lot of wind and sunshine are detrimental, whereas hedges and shade trees are planted. The soil must be deep, loose and permeable (well "aerated"), humus on top and neutral to slightly acidic.

Depending on the requirements, the growing areas are located between the tropics, at altitudes of around 600 to 1200 meters above sea level for Arabica coffee and between 300 and 800 meters above sea level for Robusta coffee. Highland coffees (Arabica) are of particularly high quality.

Man-made climate change could soon cause the area under coffee cultivation to shrink significantly. The rise in average temperatures, the change in the seasonal distribution of precipitation and extreme weather events are making it increasingly difficult for coffee farmers. As a result, a fungal disease that is now widespread around the world is also spreading: Coffee rust.

Propagation and care

Coffee is propagated by seed, cuttings or by grafting, mostly by seed. The seeds (coffee beans) have the highest germination capacity eight weeks after fruit ripening, after which it decreases. They are freed from the parchment and sown in seedbeds. The first two leaves of the seedling appear after five to six weeks. Then the seedlings are transplanted into containers and further cultivated in nursery beds. At the age of eight months, they are planted in the plantation, at intervals of one to four meters, depending on the variety. They are pruned in height as they continue to grow, to 1.5 to 3 metres as required. At the age of three to five years, the yield is optimal and remains maximum for 10 to 20 years, after which it decreases.

Environmental impact

Growing coffee has a significant impact on the environment. Traditionally, coffee has been grown in the shade of surrounding large trees. This method preserves part of the natural habitat, which is associated with a significantly higher biodiversity. In places, the diversity even approaches that of virgin forest, although it usually decreases as a result of cultivation. Because coffee grown in this way takes longer to mature and there are fewer coffee plants per hectare, many coffee farmers (exacerbated by falling world market prices due to the coffee crisisNote:) have turned to clearing existing trees and growing coffee beans in large monocultures in the open air. Existing studies show a drastic effect on biodiversity. Among other things, American migratory birds no longer find shelter in the tree-free plantations, and the balance of pests and beneficial insects that can be observed in traditional coffee cultivation is attempted to be balanced by the use of environmentally harmful pesticides.

According to the environmental organisation WWF, there is a close link between the 'sun coffee' described above and tropical deforestation. Among the 50 countries with the highest deforestation rate in the years 1990 to 1995 are 37 producers of coffee. The top 25 coffee exporters lost 70,000 km² of forest land annually during the same period. The result is a significant decline in biodiversity, in the case of birds by up to 90%. Other consequences include increased soil erosion, especially in shifting cultivation and with the use of herbicides, which destroy the protective vegetation layer of the soil, and declining water quality around coffee plantations. The latter is well illustrated by the calculation that a total of 140 litres of virtual water are required for the cultivation, roasting, shipping and preparation of a cup of coffee.

The environmental impact of organic coffee cultivation is significantly lower. In organic cultivation, among other things, the use of pesticides is prohibited, while at the same time measures must be taken to prevent soil erosion. At the same time, the income of some organic coffee farmers can be stabilized, which is the case in Chiapas, Mexico, for example. In 2010, about 6.5% of the world's coffee-growing area was organic, with over 90% of this area in Peru, Ethiopia and Mexico.

Social consequences

Coffee is still tainted with the stigma of child labour. In Kenya, 60% of coffee workers are children. More than 30% of the coffee harvest in Guatemala is harvested by children. In Ethiopia, 53% of all children under 14 work. It is probably difficult to judge from the outside whether children only work occasionally in addition to school or whether they do gainful employment like adults instead of school. Therefore, figures are always uncertain. It is generally assumed that the proceeds from the coffee beans must be sufficiently high for the farmers to be able to send their children to school and not be dependent on their work.

In order to find a way out of this situation, Fair Trade has developed. The basic idea is to certify to the consumer that the product has been produced under correct social conditions. For this purpose, certificates and licenses are issued for a fee. Part of this revenue is supposed to benefit the farmers. The system has come under criticism for lack of transparency and high costs for farmers. Official standards are lacking.

Many small roasters therefore prefer to go the direct trade route: they buy the coffee directly from the farmers or cooperatives, without the intermediate step via the international coffee traders. Often the pricing is kept very transparent, the customer learns from which farmer or cooperative the product comes and what price was paid to the producer.

There are no legal regulations for either fair trade or direct trade. Buying coffee remains a matter of trust. In Germany, a coffee tax of 2.19 €/kg roasted coffee is levied. Coffee that has been traded under decent social conditions is not available at bargain prices.

Harvest

Harvesting takes place once a year, in some growing regions also twice. North of the equator the harvest is from July to December, south of the equator from April to August. Near the equator, harvest can be in all seasons. Harvesting takes up to ten or even twelve weeks because the fruits take different lengths of time to ripen, even on the same bush. If the fruit is picked by hand in such a way that only the ripe fruit is harvested, a better quality is achieved. Arabica coffee in particular is picked selectively by hand using the so-called "picking method". Lower quality has to be accepted if all fruits are stripped by hand or by machines, regardless of their degree of ripeness ("stripping method"), in order to save labour. However, re-sorting improves quality in the process. Strip harvesting is used for Robusta coffee and for Arabica coffee in Brazil and Ethiopia, which is then dry processed (see processing). Harvesters are used on large plantations in Brazil.

The world average green coffee yield is about 680 kg/ha, in Angola 33 kg/ha, in Costa Rica 1620 kg/ha, new plantations in Brazil yield 4200 kg/ha. To obtain a bag of 60 kg of green coffee, it is necessary to harvest 100 good bearing Arabica trees.

Editing

During processing, the skin of the fruit, the pulp, the mucilage on the parchment skin, the parchment skin and - as far as possible - the silver skin are removed in order to obtain green coffee.

This can be achieved by dry means as well as by wet means. When deciding which processing method to use, the aim is usually to avoid defects and quality losses as far as possible, as these affect the price and can represent an existential risk for coffee farmers. Increasingly, however, there are farmers who use specific processing methods to deliberately influence the taste of the coffee. Natural coffees tend to be sweeter and more full-bodied than washed coffees. In contrast, wet-processed beans are valued for their complex and clear flavor profile. Blends try to bring out the clarity of the coffee while retaining a slight sweetness and more "body" to the coffee.

| Coffee preparation process by geography | ||

| Type | Wet processing | Dry processing |

| Robusta | Asia (Indonesia, India, Papua New Guinea) | Africa (Uganda, Angola, Tanzania) |

| Arabica | Standard procedures outside Brazil | Brazil and up to 10 % in other countries |

The very rare and expensive Indonesian Kopi Luwak undergoes an additional and special type of preparation. It is produced when the creeping cat species Luwak eats coffee cherries and excretes beans whose taste characteristics have changed due to fermentation in the animals' intestines. Among other things, bitter substances are removed in the process.

Dry processing

Dry processing involves spreading out the coffee fruits ("coffee cherries"), which contain about 50 to 60 % water, and turning them from time to time until they are dried to a water content of about 12 %. This takes about three to five weeks. After that, the dry fruit skin and flesh are mechanically peeled off.

Wet processing

Wet processing should be started within 12 hours, at the latest 24 hours, after harvesting. First, pre-cleaning is carried out with water (by hand or machine) and pre-sorting is carried out by flushing. The fruit skin and pulp are then squeezed off in a "pulper", leaving the parchment skin and adhering mucilage on the coffee beans. The beans are transported through an alluvial channel and through sieves into fermentation tanks. There, fermentation takes place, whereby the mucilage liquefies and becomes washable. After 12 to 36 hours of fermentation, the beans are washed, then spread out to dry (sun, air, hot air if necessary) and dried to a water content of about 12%. Wet processing requires 130 to 150 liters of water per kilogram of market-ready green coffee.

Semi-dry preparation

In order to save water when water is scarce and still achieve a higher quality than with dry processing, so-called semi-dry processing is used: After washing, the fruit flesh is largely squeezed off, but then it is not fermented, but dried immediately. Then, as in dry processing, the dry fruit skin and pulp are peeled off the coffee beans.

Clean

After preparation, the coffee beans are still surrounded by the parchment skin (known as "parchment coffee"). The parchment skin and, as far as possible, the silver skin are removed by peeling.

In a final treatment, any impurities still contained are separated and the beans are sorted - by hand in the case of high-quality coffees - i.e. sorted according to size and quality. This produces the market-ready green coffee.

Roasting

By far the largest part of the green coffee is roasted. A small proportion is also used as green coffee. In general, roasting is the dry heating of coffee beans, usually under atmospheric pressure. During this process, the roasted product undergoes various chemical and physical processes through which the roasted coffee-specific colour, flavour and aroma substances are formed. As with the roasting of other products, this is the so-called Maillard reaction. The roasting process begins at 60 °C and ends in the traditional roasting process at a bean temperature of approx. 200-250 °C, whereby the ambient temperature in the roaster is sometimes considerably higher. In the time-saving industrial roasting process, ambient temperatures of up to 550 °C prevail. The type and quality of the green coffee beans, as well as the roasting time and temperature, determine the degree of roasting and essentially influence aroma formation, development of flavours and digestibility. Fast industrial roasts at high temperature build up more harmful substances, such as melanoidins and acrylamide. Light roasts result in a more acidic but less bitter taste, while darker roasts taste slightly sweet but bitter. The sour taste in coffee is largely due to the component chlorogenic acid. It is gradually broken down during roasting. Dark roasts contain less chlorogenic acid than light roasts. While the bean temperature gradually rises during the roasting process, the so-called first crack is reached at around 200 °C: gases (mainly carbon dioxide) are produced in the beans, which lead to a sudden expansion of the bean, as with popcorn. This is why the beans are larger after roasting than before. The first crack can be clearly heard during roasting. At approx. 225 °C, the second crack occurs. Here, pieces of the bean burst off on the surface due to the heat. The second crack is much quieter than the first crack. In most cases, roasting is interrupted before the second crack, the desired degree of roasting has been reached. Due to drying, but also due to loss of substance, the roasted coffee is approx. 12-24% lighter than the green coffee, but usually around 18%. This is referred to as roasting loss.

Heat is transferred to the surface of the coffee beans by convection, radiation and contact. However, there is an increasing shift from contact to convection roasting, in which the coffee is surrounded by directly or indirectly heated air, thus improving heat transfer to the roasted product. The following roasting methods are commonly used:

- Batch roasting either in a drum roaster or in a fluidized bed roaster

- Continuous roasting, in which the coffee is transported and roasted in rotating drums with an internal transport system.

Degree of roasting

- Light roast = pale or cinnamon roast

- Medium roast = American roast, breakfast roast

- Strong roasting = light French roasting, Viennese roasting

- Double roasting = Continental roasting, French roasting

- Italian roast = Espresso roast

- Café torrefacto (Spanish for roasted coffee) = roasting with the addition of sugar, used mainly in Spain. The coffee roasted in this way is mixed with the conventionally roasted coffee (tueste natural) at a rate of 20-50%, and the result is known as a mezcla (Spanish for blend). A mezcla 70/30, for example, consists of 70% tueste natural and 30% café torrefacto. This roasting method softens the acidity and bitterness of the coffee blend.

In addition to the color of the roasted beans, the amount of roasting loss or burn-in is also used as a measure of the degree of roasting.

Trade

| Coffee export from Costa Rica 2000 to 2016 | |||

| Harvest year | Export quantity | Export value | Value/t |

| 2003 | 122.623 | 193,637 | 1.579,12 |

| 2004 | 108.565 | 197,640 | 1.820,48 |

| 2005 | 112.408 | 262,260 | 2.333,11 |

| 2006 | 96.805 | 250,195 | 2.584,53 |

| 2007 | 91.665 | 254,912 | 2.780,91 |

| 2008 | 109.777 | 337,429 | 3.073,77 |

| 2009 | 78.337 | 237,088 | 3.026,51 |

| 2010 | 74.218 | 261,841 | 3.528,00 |

| 2011 | 76.400 | 375,867 | 4.919,73 |

| 2012 | 87.148 | 418,564 | 4.919,73 |

| 2013 | 81.464 | 302,806 | 3.717,05 |

| 2014 | 72.817 | 277,330 | 3.121,94 |

| 2015 | 68.579 | 305,956 | 4.461,37 |

| 2016 | 75.495 | 307,910 | 4.078,55 |

The most important customer countries are the USA, Germany, France, Japan and Italy.

Starting at the end of 2001, the coffee price returned to a slight upward trend. Since the end of 2004, coffee prices have been rising more strongly again. For example, according to monthly averages of the International Coffee Organization's Composite Index of coffee exporters, after coffee prices generally far exceeded 100 U.S. cents per pound (lb) in the 1970s, 1980s, and mid-1990s, a low of only 41.17 U.S. cents per lb was measured in international trade in September 2001; by contrast, the twelve monthly averages of 2005 recovered to values between 78.79 (September) and 101.44 (March) U.S. cents per pound.

In addition to increased consumption leading to a balanced market, hedge funds and other speculative investors driving up prices on commodity and coffee exchanges have contributed to the increase since late 2004. Thus, the number of commodity futures traded and also outstanding has increased significantly.

fair trade

In most cases, the smallest share of the price paid by the end consumer remains in the country of cultivation itself, and of this in turn only a small share remains with the coffee farmers and plantation workers. In Fair Trade, whose classic product is coffee, attempts are made to improve this difficult economic situation of the producers throughout the entire trading process.

Germany

The coffee industry in Germany is an oligopoly: six suppliers, including Tchibo and Aldi, share 85% of the market. The major German roasters are concentrated in the Hamburg and Bremen areas. The port of Hamburg is the largest import port for coffee in Europe, while the city of Bremen handles the largest volume of coffee in Germany via the ports of Bremen and Bremerhaven. Four of the largest coffee roasting plants in Germany are located in Bremen and the surrounding area.

| Composition of the coffee price | |

|

| |

| 44,9 % | taxes, customs duties, freight charges |

| 23,7 % | Retail |

| 17,8 % | Dealers and roasters |

| 08,5 % | Plantation owner |

| 05,1 % | Wages of the workers |

| Coffee sales in Germany in 2014 | |

| Product | Quantity (t) |

| Filter coffee (ground) | 261.650 |

| Whole coffee bean | 63.450 |

| Coffee pad | 48.650 |

| Soluble coffee | 19.890 |

The share of coffees from certified sustainable cultivation was around 8 % in 2014.

As a result of the fall in prices on the coffee market, in 2001 the price of coffee had fallen to a level that had never been undercut in the previous 50 years: in 2001, the average price paid for 500 g of coffee was only 3.28 euros. For coffee producers around the world, this "coffee crisis" had far-reaching consequences.

Under the Coffee Tax Act, roasted coffee and goods containing roasted coffee are taxed. A tax of 2.19 euros/kg is levied on roasted coffee and 4.78 euros/kg on soluble coffee. The annual revenue from the coffee tax in Germany amounts to about one billion euros. Recently, some manufacturers have started to add up to 12% maltodextrin, caramel and other carbohydrates to ground roasted coffee. While manufacturers Kraft Foods and Tchibo justify this on taste grounds, this approach, along with roasting abroad, also offers companies significant tax advantages.

Pricing

→ Main article: Pricing

The quality ranking is based on the types of variety in demand from the trade. Colombian Mild varieties with a broad taste spectrum are in high demand.

Pricing is generally based on:

- production economic aspects and quality criteria

- price formation on the world market

- the specific trade structure

- multinational trade agreements and their effects

Yield gaps result from the difference between the maximum yield that can be achieved by exploiting the biological and technical possibilities under optimal conditions at experimental stations and the actual yields in agricultural practice. The global area under cultivation varies due to the current commodity prices for coffee. While the area under cultivation decreased slightly in Brazil, it expanded in the Dominican Republic, Costa Rica and Honduras. The largest increases in area were observed in Asia, particularly due to the very low labour wages in Vietnam.

Coffee is grown at different intensities: a minimum of 1.9 tonnes per hectare in subsistence farming, 1.7 tonnes per hectare in semi-shade farming and 4.9 tonnes per hectare in shade-grown farming. Due to opaque pricing and trade policies, African coffee production stagnated for some time. In Rwanda and Burundi, despite export-oriented agricultural policies, coffee revenues fell sharply as a result of the civil wars.

In economic terms, coffee supply is an almost completely inelastic short-term supply curve. A long-term supply response has a time lag of up to eight years, as it is only during this period that the optimum yield of a coffee plantation is reached. The first harvest of a newly established plantation can only be made after three to four years at the earliest. The demand of coffee is also relatively inelastic. It is a marginal and short-term price elasticityNote: for coffee between 0.1 and 0.2, as national drinking and eating habits determine consumption. Notes:

International Coffee Agreements

A one percent increase in supply would thus cause a four percent drop in price. To regulate these effects, trade was instrumentalised by means of international coffee agreements. In 1963, the first ICA (International Coffee Agreement) was concluded between producer and consumer countries and aimed to balance out price fluctuations on the world market. The ICA consisted of a set of rules consisting of export quotas and target prices, which were adjusted according to the market situation.

In 1983, further price-quota agreements and intervention prices were introduced; the quota volume was decided by a Council at that time and was based on the total quota of the exporting countries. 85% of the world market was thus controlled by intervention prices. Countries with low export and market shares did not always adhere to quota discipline, and a discrepancy emerged between producer countries with high mass shares of low-priced coffee and others with low shares but high qualities. Leaps in innovation in coffee production (Costa Rica increased its coffee yields to 2.5 t/ha) give some countries production advantages and trigger cost competition. The trade structure in coffee-producing countries is often state-directed or regulated through aggregate trade. Since foreign exchange earnings for coffee were relatively high, this agricultural commodity was often the focus of national economic policy. To ensure stable prices, supply was often artificially tightened through government intervention. 50 Third World countries were or still are heavily dependent on foreign exchange earnings from coffee exports, as 70% of the world's coffee is produced as a "cash crop" in smallholder subsistence agriculture. The harvesting of high-quality Arabica coffee requires a peasant farming system (labour intensity in Kenya for 850 kilograms of green coffee approx. 2900 labour hours).

In the importing countries there are concentrations, so that in some countries up to 95 % of total sales come from four large roasting companies. Oligopolistic organisational structures can therefore be found on both the production and sales sides. In any case, the trade margin covers the high transformation costs. The import price elasticity as a net margin is 0.3 in the Federal Republic of Germany and 0.7 in Italy as a single regression and 0.03 as a multiple regression. Coffee agreements clearly act as market stabilisers and are intended to ensure a moderate price level. If oversupply occurs, producers try to export more to non-quota countries. In Brazil, some of the quota shares have been filled with lower quality Robusta coffee. If the surpluses cannot be sold, sales are sought at dumping prices on the residual market. The former Eastern Bloc countries such as the GDR, Poland and the USSR thus received high-quality coffee at prices far below the world market price. In most cases, there is a structural overproduction in coffee production, partly due to the biological-technical progress in production and partly due to the market entry of new participants such as Vietnam, which now ranks second among the world producers due to the strong expansion of cultivation.

In 1993, the ACPC (Association of Coffee Producing Countries) was founded, and in 1996 the 5th International Coffee Agreement was adopted between 36 producer and 17 consumer nations. These countries are organized in the ICO (International Coffee Organization). In 1997, less than 30% of the 43 billion US dollars in coffee revenues went to the countries of origin of the raw material. The market situation profits from the low price policy of coffee processors such as Kraft Foods, Nestlé, Tesco, Sara Lee and Starbucks were not passed on to the producers.

Consumption

The Finns consume the most coffee in the world, followed by the Norwegians and the Swedes. In 2009, each Finnish inhabitant consumed an average of almost 8.5 kg of coffee, which corresponds to a total of 1305 cups per year or 3.6 cups per day and person. The USA has the highest total consumption, estimated at 1,216,477 tonnes in 2003 (Finland: 59,301 tonnes). These figures are equivalent to 4.2 kg per person in the USA, or 646 cups per year (1.8 per day). These figures are based on data from the International Coffee Organization (ICO) after calculating imports minus re-exports.

On average, every German consumed 6.9 kg of coffee in 2013; this corresponds to 2.6 cups of coffee per day. This makes coffee the most popular beverage among Germans, even ahead of beer.

In Switzerland, the average consumption in 2018 was 975 cups per person, up from 1110 cups in 2017.

Drum roasting machine in small roastery

Coffee roaster in a medium-sized company. Capacity of the roaster about 100 kg per batch.

Different roasting levels - from unroasted to Italian roast

Freshly shelled coffee beans with sticky parchment skin.

Coffee sorter in Dili, East Timor

Coffee harvest in Laos

.jpg)

Coffee harvest in Ethiopia

Coffee shop in Reutlingen

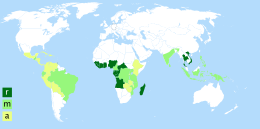

Coffee growing areas of the 14 largest coffee producers in the world: r - robusta, a - arabica, m - mixed

Coffee from fruit to plant

Preparation and consumption

→ Main article: List of coffee specialties

See also: Third coffee wave

The way coffee is prepared varies according to culture, national customs or personal taste. To make the drink, the bean is roasted and ground. The degree of roasting and grinding depends on the method of preparation.

In liquid preparation, it is infused with water; without any ingredient, black coffee or coffee black is produced. Most preparation methods use water just below the boiling point. If the water temperature is too low, the coffee tastes thin, old and sour; if the water is too hot, more bitter compounds are released from the coffee powder and it tastes bitter and burnt. Brewing with room temperature water is possible, but requires a much greater time commitment of at least eight hours. Cold Brew is a recent phenomenon, having only been included in the range internationally by larger coffee chains since 2015. Coffee can even be made with ice-cold water: Cold Drip is a special form of Cold Brew. In this process, ice cubes are added to water and dripped onto the coffee powder over a period of many hours.

- In direct infusion (family robber coffee, on estates also harvest coffee, people's coffee), ground coffee is infused directly with heated, not boiling water of about 91°C.

- In France, the method of pouring the mostly coarsely ground coffee in a press pot (also called French Press or Cafetière) is widespread. The coffee grounds are pressed to the bottom after a few minutes, usually three to five, with the help of a wire mesh. A newer variation of the press pot is the AeroPress. It works on a similar principle, but separates the water from the coffee after the brewing process.

- In pot infusion, nearly boiling water is poured over mostly coarsely ground coffee in the pot. The coffee is then poured into the cup through a metal sieve that filters the coffee grounds.

- In the Austrian Imperial and Royal Monarchy, coffee was usually boiled. In the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, coffee was usually boiled, and brewed coffee was called "Karlsbader", after the "Karlsbader Kanne", or "Karlovy Vary pot", which was needed for this purpose.

- Coffee is also brewed and drunk directly in the cup after most of the coffee powder has settled to the bottom. This is where the ancient oracle technique of reading the coffee grounds comes from.

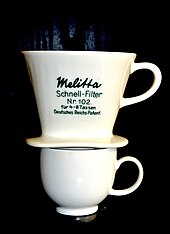

- In filter coffee, which is widely used in Central Europe and North America, hot water is added drop by drop to the coffee powder in a filter paper coffee filter. The water temperature is usually between 90 °C and 95 °C. Machines are usually used, which are available in various sizes and price ranges. Very finely ground powder can be used in this application.

- A sub-type of filter coffee is the gushing method. In contrast to the usual machine preparation, the hot water (between 90 °C and 95 °C) is not poured into the filter drop by drop, but is poured into the filter once or several times using a kettle. It has been scientifically proven that this leads to a lower level of bitterness, as the coffee grounds and water come into better contact with each other. Formerly a common preparation, the surge method has been pushed back since the advent of machines for convenience.

- In Italy, among other countries, espresso is drunk by passing water under high pressure (around 9.5 bar) through the finely ground coffee (extraction), forming a foam of coffee bean oils, the crema.

- A similar method is the preparation with so-called coffee pods. Here, a prefabricated filter bag filled with finely ground coffee is inserted into a special machine, in which the water is then pressed through. However, the pressure is lower than in an espresso machine and usually cannot be varied. Nevertheless, a crema is formed here as well.

- A very common method of preparation at home in Italy is the moka pot, which is also erroneously called espresso pot in Germany (although it cannot be used to make espresso at all). Here, the pot is heated on the stove, and hot water is forced by steam pressure from the lower chamber of the pot through a puck of coffee grounds into the upper part of the pot. The principle is therefore similar to that of the espresso machine, but the result is significantly different due to the higher water temperature as well as the lower pressure (about 1.5 to 2 bar compared to 9.5 bar in the machine). Compared to an espresso, coffee from the moka has more bitter substances and also lacks crema due to the smaller amount of dissolved oils. The name Moka should not be confused with the name Mocha.

- In Vietnam, Cà phê sữa is a coffee with sweetened condensed milk. This is also available with ice cream as Cà phê sữa đá. The roasted coffee blend may contain the Catimor and Chari types in addition to the well-known Robusta and Arabica types. This is a very dark coffee with a slightly nutty-chocolate flavor and coarser grain. These coffee blends contain the aforementioned varieties in varying blending ratios and, more rarely, also include Excelsa or Liberica beans. Due to the perception of coffee taste there, these blends cover most of the coffee needs there. Blends containing the coffee types mentioned above, which are rather unknown on the world market, are only available outside Vietnam as imported articles in Asian shops. Because of its very low caffeine content, Chari coffee is offered as a natural coffee that does not need to be decaffeinated.

- In the preparation of Turkish coffee (Turkey, Balkan countries; in Greece or in Greek pubs Greek coffee), the very finely ground coffee is boiled with water and with or without sugar in a specially designed, slightly conical copper pot, the so-called Ibrik or Cezve (/ʤɛzvɛ'/), also Dzezva or Djezva, or in Greek Briki. Various spices are sometimes added to this mocha, such as cinnamon, cardamom, or rose water. Without filtering the coffee, the drink is served together with the coffee grounds and poured into the cup; after the coffee grounds have settled, the still hot coffee is sipped without tilting the bowl too much so as not to stir up the coffee grounds.

- Soluble coffee, also known as "coffee extract", is a beverage powder that is dissolved in hot water and can be drunk without any further preparation steps. Soluble coffee is made by preparing coffee using one of the above methods and then removing the water from the prepared coffee.

Based on these basic preparations, there are hundreds of methods that use coffee. There are special coffee machines for many types of preparation. Machines for private households are already available for less than ten euros. Machines for the catering industry can be significantly larger and more expensive.

Malt coffee (muckefuck) is called coffee, but it contains malt and only slightly resembles coffee in taste. It is a food substitute (surrogate) for coffee and contains no caffeine.

Internationally, most variants are sweet. In many specialties, coffee is combined with alcoholic beverages, cocoa or dairy products. Salty coffee drinks are hardly ever prepared, although some people believe that a pinch of salt in the coffee filter has a positive effect on the taste, or alternatively that it hardens the brewing water.

Roasted coffee beans can also be chewed. Different varieties are commercially available, for example coffee beans coated with chocolate. Ground coffee is also processed for cakes, pies, ice cream and chocolates.

In Germany, the addition of coffee to tobacco products is expressly prohibited under the German Tobacco Ordinance, as is the addition of thujone, chamomile tea, guarana or mate products. (Literally: All products such as "caffeine, taurine or the following other additives and stimulating mixtures associated with energy and vitality").

Espresso cup

Powder for instant coffee

Greek coffee served from the briki

Affogato, espresso with vanilla ice cream

Ceramic coffee filter holder from the 1930s

With the Wigomat, the filter coffee machine began its triumphant advance in 1954.

Coffee grinder and continuous coffee from a portafilter machine of the manufacturer La Cimbali

Questions and Answers

Q: What is coffee?

A: Coffee is a drink made from the seeds of the coffee plant, called coffee beans.

Q: Where does the coffee plant originally grow?

A: The coffee plant originally grew in Africa, and now also grows in South America, Central America and Southeast Asia.

Q: What chemical is found in coffee?

A: Coffee contains a chemical called caffeine, a mild drug that keeps people awake.

Q: How are the beans prepared before making into a drink?

A: Before making into a drink, the beans must be specially prepared by drying them and then roasting them.

Q: What process turns the beans into a drink?

A: To turn the beans into a drink they must be roasted or ground (crushed into tiny pieces in a coffee mill) and placed into boiling water to extract their flavour and dark brown colour. This process is known as brewing coffee.

Q: Are there different ways to brew coffee?

A: Yes, there are several different ways that coffee can be brewed.

Q: What nutrients does drinking coffee provide?

A: Drinking coffee provides useful nutrients such as riboflavin, niacin, magnesium, potassium and various phenolic compounds or antioxidants.

Search within the encyclopedia