Code of Hammurabi

The Codex Hammurapi (also spelled Codex or Hammurabi and Ḫammurapi) is a Babylonian collection of legal sayings from the 18th century BC. It is also considered one of the most important and best-known literary works of ancient Mesopotamia and an important source of cuneiform legal codes (cuneiform rights). The text goes back to Hammurapi, the sixth king of the 1st dynasty of Babylon. It has been preserved on an almost completely preserved 2.25 m high diorite stele, on several basalt stele fragments of other stelae as well as in more than 30 clay tablet copies from the second and first millennium BC. This stele itself is also often referred to as the "Codex Hammurapi". It is now on display in the Louvre in Paris and, like the fragments of the basalt stelae, was found by French archaeologists in Susa, where it was taken from Babylonia in the 12th century BC. Because of this good source material, the text is now known in its entirety.

The text consists of about 8000 words, which were written down on the preserved stele in 51 columns with about 80 lines each in old Babylonian monumental cuneiform script. It can be roughly divided into three sections: a prologue of about 300 lines, which presents the divine legitimation of the king, a main section, with 282 legal sentences according to modern classification, and an epilogue of about 400 lines, which praises the righteousness of the king and calls on subsequent rulers to follow the legal sentences. The legal propositions contained in the text, which account for about eighty percent of the total text, concern constitutional law, real estate law, the law of obligations, marriage law, inheritance law, criminal law, tenancy law, and the law of cattle breeding and slavery.

Since its publication in 1902, mainly Assyriologists and jurists have dealt with the text, whose situation of origin or function (seat in life) could not be clarified until today. The original assumption that it was a systematic summary of current law (codification of law) was contradicted early on. Since then it has been discussed whether it is a private legal record (law book), model decisions, reform laws, a doctrinal text or simply a linguistic work of art. These discussions could not be concluded until today and are to a considerable extent related to the professional and cultural background of the respective authors. Theology also showed a strong interest in the Codex Hammurapi, whereby especially a possible reception of the same in the Bible was controversially discussed.

Again and again the Codex Hammurapi is referred to as the oldest "law" of mankind, a formulation which - independent of the aforementioned controversies - cannot be maintained today since the discovery of the older codices of Ur-Nammu and Lipit-Ištar.

Lore

The text of the Codex Hammurapi, which is around 3800 years old, is best known through the diorite stele now in the Louvre (Département des Antiquités orientales, inventory number Sb 8). It was found in three fragments on the acropolis of Susa in the winter of 1901/1902 by Gustave Jéquier and Jean-Vincent Scheil during a French expedition to Persia led by Jacques de Morgan. Already in April 1902 these were brought to the Paris museum, reassembled to a stele, and their inscription was edited and translated into French by Jean-Vincent Scheil in the same year. In the process, Scheil established a paragraph numbering system based on the introductory word šumma (Engl.: "if"), which resulted in a total number of 282 paragraphs for the text - a counting system that is still used today. The first German translation by Hugo Winckler, who adopted Scheil's division into paragraphs, followed in the same year.

The upper part of the stele exhibited in the Louvre shows a relief depicting King Hammurapi before the enthroned sun, truth and justice god Šamaš. Hammurapi assumes the arm posture of a praying man, which is also known from other representations, while the god presumably hands him symbols of rulership. Some scholars have also suggested that the god depicted is more likely the Babylonian city god Marduk. Below this the text of the Codex Hammurapi is carved in 51 columns of about 80 lines each. The script used was the Old Babylonian monumental script, which resembles the Sumerian cuneiform script even more than the Old Babylonian cursive script, which is known from numerous documents of this time.

Part of the text of the stele was already chiseled out in antiquity; however, this can be reconstructed on the basis of comparative pieces, so that today the entire text is known. This carving can be traced back to the Elamians, who under King Šutruk-naḫḫunte, during a campaign to Mesopotamia, carried the stele off to their capital in present-day Iran along with numerous other works of art, such as the Narām-Sîn stele. The original site of the stela is therefore unknown; however, there are repeated references to the Babylonian city of Sippar. Nine further fragments of basalt found in Susa indicate that at least three other stelae with the codex existed, which were then probably erected in other cities.

In addition to the main text in the form of the stela inscription, the Codex Hammurapi is also known from a series of clay tablets that quote parts of the text. These were discovered partly already in the 19th century, but also partly only after the discovery of the stele in Susa. They are now in the British Museum, the Louvre, the Museum of the Ancient Near East in Berlin, and the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia. As early as 1914 a large copy of §§ 90-162 was found on a clay tablet in the museum in Philadelphia, which also shows the ancient division of the paragraphs, which in some places differs from the Scheil division used today. However, copies of the text also originate from subsequent epochs and other regions of the Ancient Near East up to Neo-Babylonian times, whereby the ancient "division of paragraphs" varied considerably.

Excerpt of the text

Structure

The Codex Hammurapi follows the three-part division into prologue, main part and epilogue, which is also known from other ancient oriental legal collections. In the text of the stele from Susa, the prologue comprises 300 lines, the epilogue 400 lines. In between is the main part of the text with the actual legal sentences and a volume of about 80% of the entire work.

Prologue

The prologue of the Codex Hammurapi belongs, according to prevailing opinion, to the most important literary works of the Ancient Near East. It can be divided into three sections of meaning, which are typical for the ancient Near Eastern codices in this order:

- Theological part,

- Historical-Political Part,

- Moral-ethical part.

The theological part serves to explain Hammurapi's divine legitimation and is constructed as a long temporal sentence. In it, it is first explained that the Babylonian city-god Marduk was called to rule over mankind by Anu and Enlil, the highest gods of the Sumerian-Akkadian pantheon. Accordingly, Babylon, as his city, had also been designated as the center of the world. In order that a just order might exist in the land, that evildoers and oppression of the weak might come to an end, and that all might be well with mankind, Hammurapi was then chosen to reign over mankind.

A Neo-Babylonian copy of the prologue (BM 34914) shows that several variants of this text existed, whereby this Neo-Babylonian copy differs from the text version of the stele from Susa, especially in the theological part. Thus in this version Hammurapi is directly empowered by Anu and Enlil, while Marduk is not mentioned. Instead of Babylon, Nippur is designated as the center of the world, and the mandate to rule comes directly from Enlil, the city-god of Nippur. Possibly this is a concession of the king to the religious center of Nippur.

This is followed by the historical-political part as a self-portrayal of the king with his political career, stylized as epithets in the form of a list of his deeds in cities and sanctuaries. Since this list of cities corresponds to the cities that belonged to Hammurapi's empire in his 39th year of reign, this represents a terminus post quem for the dating of the stele from Susa. A clay tablet copy (AO 10327) contains another version of this list of cities, which can be assigned to the 35th year of his reign. From this it is clear that the stele does not contain the oldest version of the Codex Hammurapi. The only clue for an alternative dating of the text is the year name of the 22nd year of Hammurapi's reign mu alam Ḫammurapi šar (LUGAL) kittim (NÌ-SI-SÁ) (engl.: year - statue of Hammurapi as king of justice). Since this stele is also mentioned in the text of the Codex Hammurapi and its existence is thus assumed, the 21st year of Hammurapi's reign is used as an alternative terminus post quem.

The moral-ethical part follows the preceding one without establishing a geographical reference. Thus, he first explains his filiation from the founder of the dynasty Sumulael and his father Sin-muballit and refers to the leadership mandate issued by Marduk, which he followed by establishing law and order (akk.: kittum u mīšarum). The prologue concludes with the word inūmīšu (engl.: at that time), which is then followed by the actual legal sentences.

Legal records

A large number of Assyriologists and jurists dealt with the actual legal sentences, who above all tried to grasp the systematics behind them and in this way also to develop their nature. In the course of time, various approaches were presented, which, however, did not gain general recognition because of various shortcomings. This is especially true of the early attempts to create a systematics according to logical or juridical-dogmatic aspects, such as those undertaken by the Frenchman Pierre Cruveilhier.

One of the most important attempts of this kind was that of Josef Kohler, who first correctly stated that the legal sentences at the beginning of the text were primarily characterized by a relationship to "religion and kingship". These were then supposed to have been followed by "provisions on trade and change", in particular agriculture, transportation and the law of obligations, after which there would have been provisions on family and criminal law, before shipping, tenancy and service relationships and servitude rounded off the text. This was opposed in particular by David G. Lyon, with an alternative proposal for division. He assumed that the Codex Hammurapi was divided into the three main sections Introduction (§§ 1-5), Property (§§ 6-126) as well as Persons (§§ 127-282), whereby the section Property was divided into the subsections Private Property (§§ 6-25), Real Estate, Trade and Business (from § 26) and the section Persons into the subsections Family (§§ 127-195), Infringements (§§ 196-214) and Labour (§§ 215-282). This division, which has been contradicted several times, was later followed by Robert Henry Pfeiffer in order to compare the Codex Hammurapi with biblical and Roman law. Thus he named §§ 1-5 as "ius actionum", §§ 6-126 as "ius rerum" and §§ 127-282 as "ius personarum", whereby he subdivided the latter section into "ius familiae" (§§ 127-193) and "obligationes" (§§ 194-282).

In general, however, the attempt of Herbert Petschow found the most approval. He found that the order of legal propositions was based on subject groups, which separated legally related norms from each other. Within individual subject groups, the arrangement of legal rules was based on chronological criteria, the weight of the goods dealt with, the frequency of cases, the social position of the persons concerned, or simply on the case-counter-case scheme. Petschow, however, also succeeded in demonstrating that individual legal clauses were primarily arranged according to legal aspects; this includes, for example, the strict separation of contractual and non-contractual legal relationships. Basically, according to Petschow, the Codex Hammurapi can be divided into two main sections:

public policy

The first 41 legal propositions concern the public sphere, characterized by kingship, religion, and the people. They can be further divided into several sections of meaning.

The first of these sections is formed by §§ 1-5, which deal with the persons who are instrumental in the judicial determination of the law: Plaintiffs, Witnesses, and Judges. For this reason, Petschow gave this first section the title "Realization of Law and Justice in the Country" and saw in this a direct link to the concern to this effect expressed last in the prologue. These five legal sentences threaten false accusation and false testimony with punishment according to the principle of talion; for judges on the take, removal from judicial office and a pecuniary penalty amounting to twelve times the subject matter of the case were provided for.

The second section comprises §§ 6-25 and deals with "capital offences" considered particularly dangerous to the public. These are mainly property offences directed against public property (temple or palace) or against the social class of the muškēnu. In addition, there are individual other offences which were either also considered to be of public danger or were sorted into this section on the basis of attractions. What all the legal sentences of this section have in common is that they provide for the death penalty for the delinquent.

The §§ 26-41 then form the third section, which deals with "official duties". The service obligations (Akkadian ilku) are often inaccurately translated as fiefdoms, since the service obligor normally performed his service obligation on a property made available for this purpose. After stipulating penalties for violations of official duty, regulations are made above all concerning the whereabouts of the ilku property in the event of the obligor being a prisoner of war or escaping. Finally, a kind of legal power of disposal of the service obligor over his ilku property is established.

"Private Law"

The rest of the legal sentences mainly concern the individual sphere of the individual citizen. This larger group of legal sentences deals with property, family and inheritance law, but also with questions of work and physical integrity. Although they are clearly separated from the preceding section by their compilation, there is a connection in terms of content via the topic of "agriculture".

The first section is now formed here by §§ 42-67, which have the "private property law" as their subject; namely, successively fields, gardens and houses. Here, contractual legal relationships are dealt with first, which mainly takes the form of regulations on the right of lease and the right of lien. This is followed by provisions on non-contractual liability for damages.

In these legal propositions, provisions relating to the 'performance of debt obligations' are interpolated several times, which then becomes the dominant theme in §§ 68-127 and to that extent constitutes a new section. The subject of these is primarily the tamkarum (merchant). In addition, however, there are also provisions on the sabītum (innkeeper), before this section is concluded with the topics of seizure and debt enslavement.

Sections 128-193 form a clearly delimitable section dealing with "marriage, family and inheritance law". Here, the marital fiduciary duties of the wife, the husband's duties of maintenance and care, and finally the property law effects of marriage for both spouses are dealt with in turn. This is then followed by a series of criminal offences in the sexual sphere, before finally dealing with the possibilities of dissolving a marriage and its consequences in terms of property law.

This part is then followed by legal principles of the law of succession, dealing successively with the dowry on the death of the wife and the property after the death of the father of the family. The latter is further differentiated into the right of inheritance of legitimate children, the surviving widow and children of a mixed marriage. The inheritance law of daughters as a special case is separated from this by procedural provisions. This group of legal provisions is rounded off by provisions on adoption law and the law of obligation.

Another section, dealing essentially with "injuries to bodily integrity and damage to property", consists of §§ 194-240. Here, too, contractual and non-contractual legal relationships are strictly separated, with legal relationships based on tort being dealt with first. Here, as a rule, penalties are again threatened in accordance with the talion principle. Next, bodily injury and damage to property committed in the performance of contractual relationships are dealt with, always preceded here by provisions on the activity performed in accordance with the art. At the end of the section are legal propositions dealing with liability issues in ship hire, thus providing a transition to the final section.

This consists of §§ 241-282 and deals with "livestock and service rent". The legal clauses are sorted chronologically according to the chronological sequence of field cultivation from tilling the field to harvesting. Within these groups, differentiation has again been made between contractual and non-contractual liability. At the end of this section, general rent rates are set before the legal records end with provisions on slave law.

Epilogue

The Epilogue begins on the stele with a new column, setting it apart from the legal sentences. It begins first with the formula reminiscent of a colophon:

"Laws of justice which Ḫammurapi, the able king, has established and (by which he) has caused the land to take right order and good conduct."

- Back cover, column 24, lines 1-5.

Success stories follow, some of which represent a fulfillment of the orders mentioned in the prologue. In the epilogue, however, more detailed information is given about the stele itself. According to the writing of the codex, it was erected in the Esaĝila in Babylon in front of the "statue of Ḫammurapis as king of justice". From this it is concluded by some authors that the stele found in Susa originally came from Babylon and not from Sippar.

This is followed by wishes of Ḫammurapis about the realization of his justice, his own memory and for the handling of the relief. The passage used for the interpretation of the codex as legislation also comes from this section:

"Let a man who is wronged and receives a case come before my statue 'King of Justice' and have my described stele read to him and hear my exalted words and let my stele show him the case. May he see his judgment"

- Back cover, column 25, lines 3-17.

At the end of the epilogue there are exhortations to future rulers to preserve and not to change the rules of law, which are reinforced by the wish for Šamaš to bless the next ruler. This is followed by a long collection of curses, which altogether take up most of the epilogue and are directed against any influential person who does not follow the exhortations. These curses also follow a fixed scheme consisting of the name of the deity, its epithets, its relation to Ḫammurapi, and an appropriate curse.

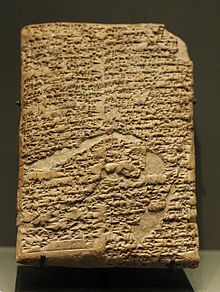

Clay tablet with the prologue of the Codex Hammurapi in the Louvre, Inv. AO 10237

Questions and Answers

Q: What is the Code of Hammurabi?

A: The Code of Hammurabi was a legal code of Babylonia written about 1700 BC.

Q: Where was the Code of Hammurabi written and where was it placed?

A: It was written on a stele (a large stone monument), and put in a public place where everyone could see it.

Q: What happened to the stele containing the Code of Hammurabi?

A: The stele was later captured by the Elamites and taken to their capital, Susa. It was found there again in 1901, and is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

Q: How many laws were written in the Code of Hammurabi?

A: The code of Hammurabi had 282 laws written by scribes on 12 tablets.

Q: In what language was the Code of Hammurabi written?

A: Unlike earlier laws, it was written in Akkadian, the daily language of Babylonia.

Q: What is the significance of the Code of Hammurabi?

A: The Code of Hammurabi is the longest-surviving text from the Old Babylonian period. The code is an early example of a law regulating a government: a kind of primitive constitution.

Q: What is the significance of the Code of Hammurabi in terms of law enforcement?

A: The code is also one of the earliest examples of the "presumption of innocence" (innocent until proven otherwise). It suggests that both the accused and accuser have the opportunity to provide evidence.

Search within the encyclopedia