Clock

![]()

This article is about the time measuring device. For other meanings, see Clock (disambiguation).

The clock is a measuring device that can indicate the current time or measure a period of time. In its history of development spanning several millennia, from the simple elementary clock to the highly precise atomic clock, it has been and continues to be in complex interaction with the cultural, technical and social development of mankind.

The clock represents a fundamental parameter of human coexistence - time. In symbolism and art it stands for the perpetual flow of time; as a vanitas motif for transience and one's own mortality. In depictions, however, it also appears as an indication of wealth or as an attribute of moderation.

Today, the watch has become an indispensable companion in the most diverse areas of everyday life. The wristwatch accompanies its wearer as a constantly available time display. The electronic watch can be found in many everyday objects, from household appliances to televisions and radio-controlled alarm clocks to computers and mobile phones.

For science and space travel, highly precise time systems (world time, atomic time) have been established, which are available everywhere through time signal transmitters and satellite radio. In astronomy, times are measured down to the millionth of a second, while the atomic clocks of GPS satellites today work better than nanoseconds and the time-of-flight measurement of electromagnetic waves even achieves accuracies of 10-14.

While elementary and wheel clocks have lost their central importance for timekeeping, they still enjoy great popularity among enthusiasts and collectors of antique pieces.

Early iron clock

Etymology

The word "clock" comes from Middle High German ūr(e)/or(glocke) ("hour", "clock"), this from Middle Low German ūr(e), which like English hour is borrowed from Old French (h)ore. Underlying is Late Latin/Italian ora, from Latin hōra, from Ancient Greek ὥρα/hóra ("time", "hour" from Urindogermanic *yōr-ā (related to year).

In English, a distinction is made between the watch (especially wristwatch and pocket watch) and the larger clock (for example as a table clock, wall clock or grandfather clock as well as large clock on towers or houses).

History and development

Ancient

→ Main article: History of timing devices

Even in ancient times, man divided his daily routine by observing the heavenly bodies, the sun and the moon. The rising and setting of the sun, as well as its highest position at noon, were distinctive points in time for people, and the time could be divided by simple markings on the wandering shadow. In ancient Egypt the shadow clock was developed from this. The days were divided into a certain number of seasonal hours, the length of which, however, changed constantly in the course of the seasons. Since the Middle Kingdom at the latest, diagonal sidereal clocks have been in use, whose hour division was based on the movements of constellations and was aligned according to the equal hour principle. Coffin texts of the respective epochs indicate that, according to Egyptian mythology, the diagonal star clocks were intended to assist the deceased in their ascent to heaven.

Since the 16th century BC, the use of the water clock is known in ancient Egypt. The official Amenemhet invented a water clock with an improved timekeeping system during the reign of Amenophis I. Water clocks consisted of a vessel into which water either flowed in or out. By the water level one could read the time independently of the daylight and in even time units. Water clocks thus allowed the use of equal, equivalent hours, which were used in a modified form in Babylonia, for example, as the Danna. Later, water clocks were also fitted with floats connected to gears, which made it possible to display the time on dials. In Greece, these clocks were used to limit the time of speech in court. The phrase "time has run out" can be traced back to this.

The technique of sundials and water clocks was adopted by the Romans and spread throughout the Imperium Romanum. In Trier, the Roman Augusta Treverorum, the foundation walls of a tower were discovered in 1913, which may have been almost identical to the Tower of the Winds, a combined sundial and water clock in Athens. It can be assumed that these techniques were known in Central Europe at the time of Rome's Germanic provinces at the latest, even if the knowledge was lost for centuries with the decline of the Roman Empire.

There followed a flourishing of science in Islamic lands. Arabs and Moors researched in various fields and made great achievements in mathematics, timekeeping and astronomy. Splendid water clocks, which were equipped with complicated figure automatons, are known from the Arabic area. One impressive example is the elephant clock of al-Jazarī, another the water clock with automata given to Charlemagne in 807 by the caliph Hārūn ar-Raschīd. In addition to water clocks, the astrolabe, originally a Greek measuring instrument for determining the positions of the stars and the time, was also further developed. The astrolabes found their way back to Europe and slowly, especially in monasteries, the scientific basis for independent manufacturing emerged. Such astrolabes can be found on many medieval monumental clocks.

Medieval

In addition to sundials and water clocks, the candle clock also became established in Europe from 900 AD. Candles of defined shapes and sizes burned for a certain length of time, and by means of markings one could read off the elapsed time. Not only could these clocks be used independently of daylight, but they were also simple to use and readily available. In addition to candles, oil lamps, slow-burning fuses and, in China, fire clocks, some with scents that changed over time, were also used.

Medieval life was regulated by a multitude of bell signals from church and town towers. Not only the prayer times of the monasteries, but also, for example, the opening times of city gates, court and market times and other important times of the day and night were rung by the towers. This required a reliable indication of the time; a necessity that the sundials and water clocks did not meet.

The escapement must be regarded as an epoch-making invention that made the development of the wheel clock possible. Gear trains had been used since pre-Christian times and complicated automata were known from Arabian water clocks, but it was the escapement that turned the free-running gear train into a clock. It is not known from when the mechanical clock was used.

The wheel clock was quickly used by doormen to indicate the correct time for striking the bells. Initially, the Türmeruhr with alarm and hour strike hung in the Türmers' parlor, later it migrated as a large, wrought-iron tower clock to the town halls, church and clock towers to show the general public the time. The rate regulator of early wheel clocks was the foliot, a simple but robust device that allowed rate accuracies of about 10 minutes per day. These clocks were set to local time using sundials or noon indicators.

The first documented mention of a wheel clock dates from 1335 and refers to a device in the chapel of the Visconti palace in Milan. With the invention of the striking clock in 1344, it was possible for the first time to read equinoctial hours mechanically. In 1370, the first publicly visible striking clock was installed in Paris on the corner tower of the Palais de la Cité, called the Tour de l'Horloge. In the 14th century, many public wheel clocks were built in Europe in quick succession, of which about 500 are still documented today. In addition, a large number of clocks can be assumed to have found no documented mention.

Above all, the findings from astronomy and mathematics had a great influence on the development of the wheel clock at this time. Some monumental astronomical clocks with a multitude of complicated displays were created during this time. Smaller iron clocks were made for European monarchs and wealthy citizens on the same principle. Although they also had astronomical displays, they mostly served representative purposes. At the same time, the change from public to domestic clocks took place.

Hourglasses became widespread in Central Europe at the same time as wheel clocks in the 14th century. The centres for their manufacture were Nuremberg and Venice, which had suitable sand deposits. Hourglasses are only suitable for measuring comparatively short time intervals and were used, for example, in shipping to determine the speed of travel and as glass clocks until the 19th century.

Initially, apart from a few individual artists, wheel clocks were mainly made and repaired by locksmiths or gunsmiths, who were already organised into guilds in the High Middle Ages. From their ranks, master craftsmen specialised in the craft of clockmaking. Independent watchmakers' guilds, e.g. in Vienna, can be traced back to as early as 1450. Very early after the invention of the iron wheel clock there were also attempts to build such clocks from wood. Also tower clocks, which were partly made of wood, are known. Contrary to common belief, the first wooden wheel clocks were by no means simple utilitarian objects, but were often ornately crafted and intended for princes or high clergy. It was not until the early 17th century that simple wooden clocks became widespread in Central Europe, especially in Switzerland, France and southern Germany.

Modern Times

The Renaissance saw two significant developments that had a decisive influence on the future path of the clock.

On the one hand, domestic clocks had been given a case to protect them from dust and thus from wear. The design of the clocks was henceforth subject to the respective taste and fashion of their time and not infrequently the function of timekeeping took a back seat to the decoration of the outer form.

On the other hand, it became possible to make the clocks ever smaller through new inventions, other materials and better tools. The use of brass for the gears meant that they could be made much smaller. The spring, already known from door locks, was adopted as an energy storage device for the clockwork and thus made them independent of the place of installation. The oldest preserved wheel clock with spring drive and spring winding dates from about 1430 ('"The Clock of Philip the Good of Burgundy" in the Germanic National Museum). Around 1504, Peter Henlein from Nuremberg was one of the first to incorporate a spring drive in combination with an unwinding mechanism into a clock, enabling it to be reduced to the size of a pocket. The watch was thus not only independent of its place of installation, it could also be worn while continuously displaying the time. Examples of the miniaturisation of the clock include a clock made in 1620 with a diameter of 5.75 lines by Martin Hylius from Dresden and one made in 1648 by Johann Ulrich Schmidt from Augsburg with a diameter of only 4 lines. From the middle of the 17th century, the first pocket watches with verge escapement were produced. Many important watchmakers in England, France and Germany produced pieces of the highest quality and competed in their constant improvement. In America one pursued another way, there one set starting from the early 19. century with industrial mass production on the production of particularly inexpensive pocket watches.

→ Main article: Pocket watch

The development of the clock was thus divided into two essential clock types, the stationary large clock and the portable small clock, which were later subject to fundamentally different requirements.

Many table clocks have survived as typical examples of Renaissance clocks. They are characterized by movements with verge escapement and wheel balance, spring barrels with power transmission via gut strings and worms, wheels made of fire-gilt brass or copper, brass movement plates and profiled pillars. Some of them have an hour or quarter hour striking mechanism on bell and alarm. The cases have a geometric basic form, are made of gilded brass or bronze and are pierced in filigree work. Rare examples have astronomical displays or fanciful, figurative automata.

Even before the introduction of the pendulum, clocks with minute hands were already being built in isolated cases. From the 16th century, pieces by Jost Bürgi are known that even had subdials for second hands, even if the accuracy of the clocks did not permit such precise timekeeping until around 1700.

On the threshold of the Baroque era, the depiction of figures and the design diversity of clock cases became increasingly important (example: Cartel clock). Especially from the German centres of Augsburg and Nuremberg, many magnificent designs with cases in animal shapes and made of precious metals such as silver and gold originated from 1600 at the latest. The mechanical precision of timekeeping receded in importance behind the fascination for the machine with its wonderful functions.

The introduction of the pendulum as a rate regulator was a revolutionary discovery that laid the foundation for scientific chronometry and the construction of precision clocks. Galileo Galilei, a brilliant scientist and pioneer of the Copernican concept of the world, described the laws of the pendulum in 1583 and discovered isochronism. He devised a mechanism with a free escapement and pendulum, but was unable to complete it during his lifetime. In 1656, the Dutch astronomer, mathematician and physicist Christiaan Huygens developed the same idea independently of Galileo and had Salomon Coster make the first pendulum clock. Only a short time later, around 1680, William Clement developed the lever escapement for large clocks. The wheel clock thus achieved an unprecedented precision of an average of a few seconds of rate deviation per day. Subsequently, the rate regulators of many old clocks were replaced by pendulums and the minute hand was generally introduced.

The focal points of watchmaking in the following period were the Netherlands and England, especially London. The basic features of the main Dutch clock types, Haagse Klok, Stoelklok and the Frisian clocks can be directly traced back to the clocks built by Salomon Coster. In England, the introduction of the lever escapement gave rise to the first floor standing clocks, the so-called Grandfather Clocks, which together with the Bracket Clocks became synonymous with English large clocks. The pendulum as a medium-sized pendulum clock to be placed on a table or a wall console developed in France (Blois and Paris) with various case styles and regional forms, and later in Switzerland (Neuchâtel and Geneva). In Germany, the importance of the pendulum was long misunderstood and so the German centres of Augsburg and Nuremberg lost their leading role and fell behind.

Between 1720 and 1780, so-called carriage clocks, especially large pocket watches with chiming and occasionally chime movements, were very popular in England as travelling clocks. They were later replaced by the carriage clock and the French pendule d'officier.

The flourishing but also competing trade of European powers with overseas colonies placed the highest demands on maritime navigation. Precise timekeeping was essential for safe navigation. The search for a solution to the longitude problem, i.e. the determination of the geographical longitude on the open sea, lasted for more than 150 years despite enormous prize money. The problem was finally solved in 1759 by John Harrison with the construction of his marine chronometers.

Modern

As a result of industrialisation, mass production of clocks developed in various centres from the middle of the 19th century onwards. In Germany, watch production in the Black Forest was particularly significant, while in France the development of the Comtoise watch may serve as an example. In the United States, the pocket watch from industrial production became especially popular. After an initial period of very high quality production, the pocket watch quickly became a successful mass product. The so-called dollar watch, a simple type of watch for everyone, was sold many millions of times by various manufacturers until the 20th century.

At the end of the 19th century, Strasser & Rhode and Sigmund Riefler developed precision pendulum clocks in Germany, which were the most accurate clocks for many years and were mainly used for timekeeping purposes and astronomical observations.

Advances in precision mechanics and later electronics also made it possible to manufacture very sophisticated pocket watches with a Grande Complication.

With the advent of widespread electricity supply, the desire quickly arose to use electricity for watches as well. A first step in this direction was the winding of clock movements by means of a mains-powered electric motor. Tower clocks with heavy weights and precision clocks that were to run as undisturbed as possible were equipped with them. Electrically wound balance clocks were used, for example, in time switches.

The rate regulator (pendulum or balance) of mechanical clocks can also be driven electromagnetically and turn the gear train via a pawl. Such clocks existed, for example, as wall clocks with a "balance" carrying permanent magnets and driven by fixed coils. Many electric pendulum clocks sold today, however, only have an apparent pendulum, the clock itself is driven by a quartz movement.

For the rapid expansion of interregional railway traffic, it was a necessity to transmit time signals over long distances. Master clocks in public clock systems sent electrical pulses to remotely located slave clocks driven by a simple stepping mechanism to synchronize the time. This also heralded the end of regional local times and led to a social change.

→ Main article: Station clock

Synchronous clocks use the mains frequency of the alternating current network as a time standard. They are inexpensive to manufacture and were widely used as large clocks in industry and public institutions.

As early as the beginning of the 19th century, miniature watches were occasionally incorporated into jewellery straps and worn on the arm. They can be seen as the forerunners of modern wristwatches, which were first mass-produced for the German navy around 1880. After the turn of the century, wristwatches initially prevailed as smart ladies' watches against the much larger pocket watches. Especially in the trench warfare of World War I, the wristwatch proved its practical advantages over the pocket watch and underwent its first significant improvements, such as luminous hands and screwed cases against moisture. But sportsmen and aviators were also early to rely on the advantages of the wristwatch.

The final breakthrough for the wristwatch came with the invention of the automatic watch by John Harwood (1923) and the introduction of the waterproof watch by Hans Wilsdorf (Rolex Oyster, 1926). The development of shock protectors was a further step towards suitability for everyday use. By 1930, the wristwatch had already reached the sales figures of pocket watches, and by 1934 it dominated two-thirds of the market.

→ Main article: Wristwatch

The first quartz clock was developed in 1921 by H. M. Dadourian, based on ultrasonic experiments with oscillating crystals carried out by Paul Langevin shortly after the First World War. The clock of a quartz clock is not a mechanical pendulum or a balance wheel, but an electronic quartz oscillator whose frequency is maintained particularly precisely with the aid of an oscillating quartz.

Initially, such watches were not available as consumer goods, but in the early 1970s they became established on the market due to their high accuracy at a moderate price and very low maintenance requirements, leading the traditional watch industry into the quartz crisis. The classic wheel watch was completely displaced by the quartz watch in almost all walks of life. For some years now, it has been experiencing a remarkable revival as a wristwatch.

→ Main article: Quartz watch

A final step towards the currently highest accuracy of time measurement was the development of the atomic clock, which was used for the first time in 1949. Atomic clocks use the radiation transitions of free atoms or ions as a timer and are used in science, for navigation in space travel and as a time standard.

→ Main article: Atomic clock

Clocks whose time display is controlled by a radio signal are called radio-controlled clocks. Since the 1960s, all accessible radio-controlled clocks in Central Europe can be synchronized by time services. Since 1966 they have been synchronized by the first European time signal transmitter HBG with atomic clocks of the Federal Office of Metrology and since 1967 by the time signal transmitter DCF77 with an atomic clock of the Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt. The Bureau International des Poids et Mesures in Paris determines the International Atomic Time (TAI) as reference time from the measured values of more than 260 atomic clocks at more than 60 institutes worldwide. In recent years, a whole variety of additional electronic distribution mechanisms for time signals have been established, which are accessible via the RDS service of VHF car radios, the teletext and the Electronic Program Guide (EPG) of television and via the NTP protocol of the Internet.

→ Main article: Time signal transmitter

Many people use the time display on their mobile phones and smartphones. These are mostly synchronized via their network provider or via the general internet.

Milestones and important discoveries

- Around 1300: first evidence of the wheel clock with mechanical escapement

- around 1425: invention of the "modern" sundial with pole bar parallel to the earth's axis

- around 1430: Invention of the spring drive for spring-wound clocks

- 1510: "Pocket watch" by Peter Henlein (Nuremberg egg)

- 1583: Discovery of isochronism by Galileo

- 1656: rediscovery of isochronism by Christiaan Huygens, application in the pendulum clock

- 1667: Beginnings of watchmaking in the Black Forest

- 1674: Invention of the balance wheel by Jean de Hautefeuille and Christiaan Huygens

- 1676: William Clement introduces the hooked gait

- Around 1680: Invention of the repeater for pocket watches by Daniel Quare or Edward Barlow

- 1700: first use of rubies as bearing jewels

- 1715: Invention of the resting anchor gear by George Graham

- 1726: Invention of the rust pendulum by Harrison

- 1726: Invention of the mercury compensating pendulum by Graham

- 1730: first cuckoo clock by Anton Ketterer

- 1741: Invention of the pin escapement by Louis Amant

- 1750: Invention of the free anchor passage by Thomas Mudge

- 1756: first pocket watches with automatic winding in Switzerland

- 1759: Solution of the length problem by John Harrison

- 1775: Invention of the automatic winding mechanism for pocket watches by Abraham-Louis Perrelet or Hubert Sarton.

- 1790: Invention of the parachute shock protection of the balance staff by Abraham Louis Breguet

- 1795: Invention of the bent-up end curve of the flat spiral ("Breguet spiral")

- Around 1800: Invention of the tourbillon by Abraham Louis Breguet

- 1810/1812: first wristwatch in the world (by Abraham Louis Breguet)

- 1842: first pocket watch with crown winding (Remontoir watch) by Adrien Philippe

- 1884: Introduction of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) as the first universally valid world time

- 1889: Precision timekeeper by Sigmund Riefler

- 1896: Discovery of the Elinvar by Charles Édouard Guillaume

- 1907: first radio telegraphic time signal transmitter starts operation in Camperdown, Halifax

- 1914: first ideas for the automatic wristwatch by John Harwood

- 1927: Quartz watch by Warren Alwin Marrison

- 1928: Replacement of the world time from GMT to Universal Time (UT)

- 1949: Invention of the atomic clock

- 1958: Introduction of the International Atomic Time TAI

- 1967: Invention of the radio-controlled clock Wolfgang Hilberg (Telefunken - patent)

- 1972: Replacement of the world time from UT to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)

- 1976: Invention of the lubrication-free co-axial escapement by George Daniels

- 1980: Introduction of the GPS time scale

- 1985: David L. Mills publishes the Network Time Protocol (NTP)

- 1985: Invention of the perpetual calendar with year for mechanical wristwatches by Kurt Klaus

- 1995: Annual world production of watches exceeds the billion mark

- 2002: The IEEE publishes the Precision Time Protocol (PTP).

Pocket watch as shop sign

Kitchen clock with short time alarm (1956)

One of the caesium atomic clocks of the PTB in Braunschweig

Digital radio clock

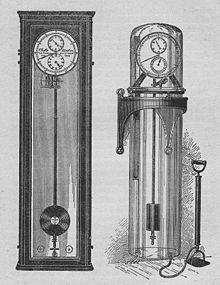

Precision pendulum clocks by Sigmund Riefler

John Harrison's Chronometer H5

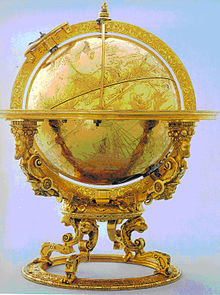

Jost Bürgi: Mechanical celestial globe, made in Kassel in 1594, now in the Swiss National Museum in Zurich

Table clock after Peter Henlein (replica)

Pendant clock, signed by Charles Bobinet, Paris circa 1650

Astronomical clock at the city hall Heilbronn

Replica of a turret clock

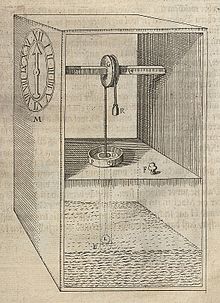

Water clock with float, counterweight and dial for time indication

Ancient sundial (Skáphe)

Questions and Answers

Q: What is a clock?

A: A clock is a device that tells the time.

Q: What are some things that other clocks can show besides time?

A: Other clocks can show the date, temperature, weather, stopwatch, and alarm.

Q: How many types of clocks are mentioned in the text?

A: Two types of clocks are mentioned in the text.

Q: What are some examples of information that some clocks can show?

A: Some clocks can show the temperature, weather, and stopwatch.

Q: Is it possible for a clock to show only the time?

A: Yes, it is possible for a clock to show only the time.

Q: What is the purpose of a stopwatch in a clock?

A: The purpose of a stopwatch in a clock is to time an event or activity.

Q: What is the purpose of an alarm in a clock?

A: The purpose of an alarm in a clock is to sound an alert according to a specific time set.

Search within the encyclopedia